- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •Contents

- •The Team

- •The Instruments

- •Patient Positioning

- •Setup for Upper Abdominal Surgery

- •Setup for Lower Abdominal Surgery

- •The Working Environment

- •Appraisal of Surgical Instruments

- •Trocars

- •Other Instrumental Requirements

- •Troubleshooting Loss of Pneumoperitoneum

- •Principles of Hemostasis

- •Control of Bleeding of Unnamed Vessels

- •Control of Bleeding of a Main Named Vessel

- •Selected Further Reading

- •2 Cholecystectomy

- •Impacted Stone (Hydrops, Empyema, Early Mirizzi)

- •Adhesions Due to Previous Upper Midline Laparotomy

- •Selected Further Reading

- •Selected Further Reading

- •The Need for Specialized Equipment

- •Access to the Liver

- •Maneuvers Common to All Laparoscopic Liver Surgery

- •Resection of Liver Tumors

- •Limited Resection of Minor Lesions

- •Left Lateral Segmentectomy

- •Right Hepatectomy

- •Patient Selection

- •Principles of Surgical Therapy in the Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

- •Patient Positioning

- •Technique

- •Postoperative Course

- •Management of Complications

- •Paraesophageal Hernia

- •Esophageal Myotomy for Achalasia

- •Vagotomies

- •Bilateral Truncal Vagotomy

- •Highly Selective Vagotomy

- •Lesser Curvature Seromyotomy and Posterior Truncal Vagotomy

- •Selected Further Reading

- •Pyloroplasty

- •Vagotomy with Antrectomy or any Distal Gastrectomy

- •Port Placement

- •Technique

- •Locating the Perforation

- •Abdominal Washout

- •Closure of the Perforation with an Omental Patch

- •Postoperative Course

- •Selected Further Reading

- •7 Appendectomy

- •OR Setup and Port Placement

- •Technique

- •Gangrenous or Perforated Appendicitis

- •Laparoscopic Assisted Appendectomy

- •Left Hemicolectomy

- •Reversing the Hartmann Procedure

- •Selected Further Reading

- •Selected Further Reading

- •Transabdominal Preperitoneal Repair (TAPP)

- •Patient and Port Positioning

- •Dissection of the Preperitoneal Space

- •Dissection of the Cord Structures and the Vas Deferens

- •Placement of the Mesh and Fixation

- •Closure of the Peritoneum

- •Indications

- •Technique

- •Positioning

- •Pneumoperitoneum

- •Port Placement

- •Adhesiolysis

- •Measurement of the Hernia Defect

- •Placement of Mesh

- •Difficult Ventral or Incisional Hernias

- •Pain Following Laparoscopic Ventral or Incisional Hernia Repair

- •Preoperative Requirements and Workup

- •Patient Positioning

- •Port Placement

- •Surgical Anatomy

- •Surgical Principles

- •Technique

- •Division of the Short Gastric Vessels and Exposure of the Tail of the Pancreas

- •Division of the Hilar Vessels and Phrenic Attachments

- •Extraction of the Spleen in a Bag

- •Final Steps of the Procedure

- •Control of an Unnamed Vessel

- •Control of a Major Vessel

- •Splenic Injury

- •Maneuver of Last Resort During Bleeding of the Hilar Vessels

- •Distal Splenopancreatectomy

- •Selected Further Reading

- •13 Adrenalectomy

- •Principles

- •Patient Positioning

- •Technique

- •Immediate Postoperative Complications

- •Late Postoperative Complications

- •Laparoscopic Adjustable Band

- •Technique

- •Complications

- •Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy

- •Selected Further Reading

- •Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

- •Laparoscopic Appendectomy

- •Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair

- •Selected Further Reading

- •Monitors

- •OR Table

- •Trocar Placement and Triangulation

- •Equipment

- •Needle Holders

- •Graspers

- •Suture Material

- •Intracorporeal Knot-Tying

- •Interrupted Stitch

- •Running Stitch

- •Pirouette

- •Extracorporeal Knot-Tying

- •Roeder’s Knot

- •Endoloop

- •Troubleshooting

- •Lost Needle

- •Short Suture

- •Subject Index

160 |

Chapter 10 Inguinal Hernia Repair |

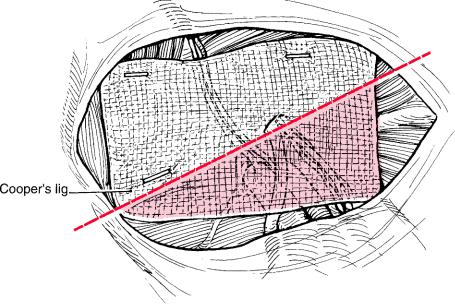

Fig. 10.14 Fixation of the mesh: showing the area in which no staples should be applied

Usually two staples are placed in Cooper’s ligament and one or two in the rectus muscle. Finally, one staple laterally completes fixation of the mesh above the iliopubic tract (Fig. 10.14). Hence, a stapler with 20 staples should be sufficient for fixation of the mesh and closure of the peritoneum.

Staples or tacks are used in laparoscopic hernia repair because the mesh is smaller than that used in open surgery (as with the giant prosthesis in the Stoppa repair), so there is a slight risk of movement immediately after surgery and for perhaps 5–7 days until the inflammatory process helps to anchor the mesh.

Closure of the Peritoneum

With the mesh now secured in place, the pressure of the pneumoperitoneum is reduced to 9 mmHg.The peritoneal flap is replaced over the mesh and is closed with tacks.At this point, the tacks being used are absorbable to prevent future adhesions to the tacks. It is essential to cover the mesh completely with the flap to prevent exposure of the mesh to the underlying small bowel, thus leading to creation of adhesions and possible small bowel obstruction.

Ideally, tacking is performed in an overlap fashion (Fig. 10.15). If tacks are not available, a continuous running suture can be used to close the peritoneal flap. In order to avoid knot-tying,which might be tedious,a blocking Laparotie clip (Ethicon EndoSurgery, Cincinnati, OH) can be used to block the knot on each side (Fig. 10.16). After removal of the ports, the skin incisions are closed with single interrupted stitches after careful closure of the fascia in the 10 mm trocar port.

Transabdominal Preperitoneal Repair (TAPP) |

161 |

a

b

Fig. 10.15 (a) Incorrect and (b) correct peritoneal closures

Fig. 10.16 Closure of the peritoneum using a running suture

162 |

Chapter 10 Inguinal Hernia Repair |

Management

of Large

Indirect Hernias

For a large indirect hernia, the standard transabdominal preperitoneal hernia repair is difficult, because the sac is usually large and firmly adherent on its superior aspect to the elements of the spermatic cord; a special technique is used to overcome these difficulties.

Dissection begins with gentle and atraumatic separation of the sac from the spermatic cord structures. This is usually carried out using scissors with sharp dissection. As the sac is separated, it is divided, but care should always be taken to ensure that the vas is not included in the sac. It is sometimes easier to identify the vas before division of the sac commences, but usually a gradual division of the sac will allow complete separation of the sac from the cord. If oozing of blood obscures the view, the operative site should be either irrigated and aspirated or wiped with a laparoscopic 2 × 2 inch gauze. Once the peritoneal sac is completely separated from the cord, the operation proceeds as usual. The distal part of the divided sac is left open in the inguinal canal, and the proximal part of the sac is ligated using an endoloop or clips.

Totally

Preperitoneal

Hernia Repair

(TEP)

Knowledge of the anatomy of the abdominal wall muscles, and more specifically recognition of the transition zone that occurs at the arcuate line of Douglas, is key to the success of the preperitoneal repair (Fig. 10.17).

The arcuate line of Douglas is a transitional line. Above the arcuate line, the rectus muscle has one defined anterior and posterior sheet made by aponeurotic fascia of the internal oblique and transversus abdominous muscle. Below the arcuate line, all fascial layers of the abdominal muscles lie in front of the rectus muscle, and behind the rectus muscle itself there is only the transversalis fascia. It is therefore essential to get below the arcuate line in order to start the preperitoneal dissection, which is located approximately midway between the umbilicus and the pubis (Fig. 10.18).

Fig. 10.17 Anatomy of the muscles of the abdominal wall

Totally Preperitoneal Hernia Repair (TEP) |

163 |

Fig. 10.18 Hernia repair: A division of anterior rectus sheet; B retraction of rectus muscle; C oblique dissection above posterior rectus sheet; D entry to the preperitoneal space

Fig. 10.19 Laparoscopic view of the preperitoneal space

The operation is started by making an incision in the umbilicus. Two retractors are used to slide the lips of the incision to the right if the hernia is located on the right side, or to the left if the hernia is located on that side. The anterior rectus sheath on the side of the hernia is then opened under direct vision, and two stay sutures of 2–0 vicryl are placed on each edge. The rectus muscle is then separated by two retractors introduced into the rectus muscle itself so that the posterior fascia can be visualized.

It is imperative at this point not to cross the posterior fascia of the rectus muscle but instead to head downwards towards the symphysis pubis in an oblique fashion using either the index finger or a small peanut with an angulation of about 30°. That will lead to the preperitoneal space below the arcuate line of Douglas (Fig. 10.19).

At this point, the preperitoneal space is dissected using a balloon spacer under direct vision with a 0° laparoscope (Fig. 10.20). While the balloon is inflated, the rectus muscle should be seen anterior and superior, and the preperitoneal fat and peritoneum

164 |

Chapter 10 Inguinal Hernia Repair |

Fig. 10.20 Balloon dissection of the preperitoneal space

should be seen posterior. One should be careful to dissect in such a way that the inferior epigastric vessels stay with the rectus muscle, as otherwise they will be in the way of dissection and may need to be ligated. The balloon should stay in place for about 15 s to tamponade any bleeding. Next, the Hasson port is introduced with a video laparoscope, using the same angulation of about 30°.

Two 5-mm ports are placed at midline between the umbilicus and the symphysis pubis to operate on both sides (Fig. 10.6b). Care should be taken not to perforate the peritoneum, which will result in pneumoperitoneum and loss of space. It is obvious that the space created using this technique is small and the movements of the instruments are accordingly limited. Perforation of the peritoneum will allow CO2 to escape into the abdominal cavity, which will subsequently compress the space and reduce it further. If this occurs, the pressures in the abdomen and the preperitoneal space must be allowed to balance before dissection continues. This is done by opening the peritoneal defect widely and inserting a Veress needle into the abdomen to allow the exit of CO2. The perforation can be closed using an endoloop or a 5-mm clip applier.

After all ports are in place, it is imperative to proceed in the following manner: Cooper’s ligament is identified medially with extreme importance placed on identification of the fluttering of the iliac vein. These two structures are the key anatomical landmarks in this procedure, as they will aid in defining the inferior aspect of the dissection. All dissections occur above this level. It is possible to injure the iliac vein, and we have seen reports of ligation of the iliac vein, which had been mistaken for a hernia sac. Once the iliac vein is identified with a careful dissection, the next step is the identification of the inferior epigastric vessels. This will delineate the internal ring and the triangle of Hasselbach. Following the internal ring medially and towards the iliac vein, one can always find the vas deferens. Once the vas deferens is dissected out, the cord structures are also separated from the sac using a soft and gentle blunt dissection. These structures are usually found behind the sac. The sac is then separated from the cord structures and vas deferens, and in this situation there are two possible scenarios. The first is a small sac that can be easily reduced.

Totally Preperitoneal Hernia Repair (TEP) |

165 |

The second is a large sac, in which case we recommend amputating the sac while paying attention to its contents and leaving the distal part of the sac open in the internal ring of the inguinal canal, and closing the proximal opening either with clips or a loop. One trick is to insert a small silk suture and tie a knot, thus effectively ligating the sac before amputating it, avoiding a loss of insufflation of the preperitoneal space and preventing pneumoperitoneum.Once the mesh is placed,we recommend using fibrin sealant (Tisseel) to fix the mesh in lieu of tackers (Fig. 10.11). This is done using an aerosol spray, attached to one of the open trocars, so there is no excessive pressure inside the abdomen. It is not important to differentiate the application of Tisseel under the mesh or above the mesh, as both will achieve the same results. It is important to always use the most lightweight large pore mesh, so as to avoid or minimize the risk of contraction of the mesh through foreign body reaction.

The operation ends by gradually removing each port, starting laterally. A grasper is left to keep the mesh in place. Finally, the last port for the camera is removed.

The obvious advantage of this technique over the transabdominal approach is that the peritoneum does not have to be closed over the mesh. The potential complications that may be associated with the transabdominal approach are avoided, as the peritoneum is not entered.

166 |

Chapter 10 Inguinal Hernia Repair |

Selected

Further

Reading

Avery C, Foley RJ, Prasad A (1995) Simplifying mesh placement during laparoscopic hernia repair. Br J Surg 82(5):642

Avital S, Werbin N (1997) Conventional versus laparoscopic surgery for inguinal-hernia repair. N Engl J Med 337(15):1089–1090

Banerjee AK (1995) Laparoscopic alternatives for the repair of inguinal hernias. Ann Surg 222(2):213–214

Barkun IS, Wexler MJ, Hinchey EJ, Thibeault D, Meakins JL (1995) Laparoscopic versus open inguinal herniorrhaphy: preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. Surgery 118(4):703–709

Brooks DC (1994) A prospective comparison of laparoscopic and tension-free open herniorrhaphy. Arch Surg 129(4):361–366

Cornell RB, Kerlakian GM (1994) Early complications and outcomes of the current technique of transperitoneal laparoscopic herniorrhaphy and a comparison to the traditional open approach. Am J Surg 168(3):275–279

Dahlstrand U, Wollert S, Nordin P, Sandblom G, Gunnarsson U (2009) Emergency femoral hernia repair: a study based on a national register. Ann Surg 249(4):672–676

Deans GT, Wilson MS, Royston CM, Brough WA (1995) Recurrent inguinal hernia after laparoscopic repair: possible cause and prevention. Br J Surg 82(4):539–541

Evans MD, Williams GL, Stephenson BM (2009) Low recurrence rate after laparoscopic (TEP) and open (Lichtenstein) inguinal hernia repair: a randomized, multicenter trial with 5-year follow-up. Ann Surg 250(2):354–355

Fitzgibbons RI Jr, Salerno GM, Filipi CJ, Hunter WJ, Watson P (1994) A laparoscopic intraperitoneal onlay mesh technique for the repair of an indirect inguinal hernia. Ann Surg 219(2):144–156

Fitzgibbons RJ Jr, Camps I, Cornet DA et al (1995a) Laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy. Results of a multicenter trial. Ann Surg 221(1):3–13

Fitzgibbons R, Katkhouda N, McKernan JB, Steffes B et al (1995b) Laparoscopic Inguinal Herniorraphy, results of a Multicentric trial. Ann Surg 221:3–13

Fujita T (2009) Laparoscopic versus open mesh repair for inguinal hernia. Ann Surg 250(2):353–354

Geraghty JG, Grace PA, Quereshi A, Bouchier-Hayes D, Osborne DH (1994) Simple new technique for laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 81(1):93

Hallén M, Bergenfelz A, Westerdahl J (2008) Laparoscopic extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair versus open mesh repair: long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Surgery 143(3):313–317

Hetz SP, Holcomb JB (1996) Combined laparoscopic exploration and repair of inguinal hernias. J Am Colt Surg 182(4):364–366

Horgan LF, Shelton JC, ORiordan DC, Moore DP, Winslet MC, Davidson BR (1996) Strengths and weaknesses of laparoscopic and open mesh inguinal hernia repair: a randomized controlled experimental study. Br J Surg 83(10):1463–1467

Jacobs DO (2004) Mesh repair of inguinal hernias–redux. N Engl J Med 350(18): 1895–1897

Kald A, Smedh K, Anderberg B (1995) Laparoscopic groin hernia repair: results of 200 consecutive herniorraphies. Br J Surg 82(5):618–620

Katkhouda N, Mouiel J (1992) Laparoscopic Treatment of Inguinal Hernia of the Adult. Chirugie Endoscopique 3:7–10

Katkhouda N, Mouiel J (1993) Laparoscopic treatment of inguinal hernia. A personal approach. Endosc Surg New Technol 1:193–197

Katkhouda N,Campos GMR,Mavor E,Trussler A,Khalil M,Stoppa R (1999) Laparoscopic extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair.A safe approach based on the understanding of the anatomy of the rectus sheath. Surg Endosc 13:1243–1246

Selected Further Reading |

167 |

Katkhouda N, Mavor E, Friedlander MH, Mason RJ, Kiyabu M, Grant SW, Achanta K, Kirkman EL, Narayanan K, Essani R (2001) Use of fibrin sealant for prosthetic mesh fixation in laparoscopic extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair. Ann Surg 233(1):18–25 Kouhia ST, Huttunen R, Silvasti SO, Heiskanen JT, Ahtola H, Uotila-Nieminen M, Kiviniemi VV, Hakala T (2009) Lichtenstein hernioplasty versus totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic hernioplasty in treatment of recurrent inguinal hernia–a prospec-

tive randomized trial. Ann Surg 249(3):384–387

Kozol R, Lange PM, Kosir M et al (1997) A prospective, randomized study of open vs laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. An assessment of postoperative pain. Arch Surg 132(3):292–295

Lawrence K, McWhinnie D, Goodwin A et al (1995) Randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic versus open repair of inguinal hernia: early results. Br Med J 311(7011): 981–985

Liem MS, Kallewaard JW, de Smet AM, van Vroonhoven TJ (1995) Does hypercarbia develop faster during laparoscopic herniorrhaphy than during laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Assessment with continuous blood gas monitoring. Anes Analg 81(6): 1243–1249

Liem MS, van der Graaf CJ (1997) Comparison of conventional anterior surgery and laparo scopic surgery for inguinal hernia repair. N Engl J Med 336(22):1541–1547

Liem MS, van der Graaf Y, Zwart RC, Geurts I, van Vroonhoven TJ (1997) A randomized comparison of physical performance following laparoscopic and open inguinal hernia repair. The Coala Trial Group. Br J Surg 84(1):64–67

Liem MS, van Steensel CJ, Boelhouwer RU et al (1996) The learning curve for totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Am J Surg 171(2):281–285

Liem MS, van Vroonhoven TJ (1996) Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 83(9):1197–1204

Lowham AS, Filipi CJ, Fitzgibbons RJ Jr et al (1997) Mechanisms of hernia recurrence after peritoneal mesh repair. Traditional and laparoscopic. Ann Surg 225(4):422–431 Memon MA, Rice D, Donohue JH (1997) Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy. J Am Coil Surg

184(3):325–335

Moreno-Egea A, Torralba Martínez JA, Morales Cuenca G, Aguayo Albasini JL (2004) Randomized clinical trial of fixation vs nonfixation of mesh in total extraperitoneal inguinal hernioplasty. Arch Surg 139(12):1376–1379

Neumayer L, Giobbie-Hurder A, Jonasson O, Fitzgibbons R Jr, Dunlop D, Gibbs J, Reda D, Henderson W; Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program 456 Investigators (2004) Open mesh versus laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal hernia. N Engl J Med 29;350(18):1819–1827

Novik B (2005) Randomized trial of fixation vs nonfixation of mesh in total extraperitoneal inguinal hernioplasty. Arch Surg 140(8):811–812

Oka M, Hiwaki K, Takao K, lizuka N,Yamamoto K, Suzuki T (1996) The saline ballooning method for peritoneal dissection during laparoscopic herniorrhaphy. Arch Surg 131(4):448–449

Olmi S, Scaini A, Erba L, Guaglio M, Croce E (2007) Quantification of pain in laparoscopic transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) inguinal hernioplasty identifies marked differences between prosthesis fixation systems. Surgery 142(1):40–46

Panton ON, Panton RJ (1994) Laparoscopic hernia repair. Am J Surg 167(5):535–537 Payne JH Jr,Grininger LM,Izawa MT,Podoll EF,Lindahl PT,Balfour J (1994) Laparoscopic

or open inguinal herniorrhaphy? A randomized prospective trial. Arch Surg 129(9): 973–979

Sampath P,Yeo CT, Campbell TN (1995) Nerve injury associated with laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy. Surgery 118(5):829–833

168 Chapter 10 Inguinal Hernia Repair

Sandbilcher P, Draxl H, Gstir H et al (1996) Laparoscopic repair of recurrent inguinal hernias. Am J Surg 171(3):366–368

Stoker DL, Speigelhalter DJ, Singh R, Wellwood JM (1994) Laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair: randomized prospective trial. Lancet 343(8908):1243–1245

Swanstrom LL (1996) Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy. Surg Clin N Am 76(3):483–491 Vogt DM, Curet MJ, Pitcher DE, Martin DT, Zucker KA (1995) Preliminary results of a

prospective randomized trial of laparoscopic onlay versus conventional inguinal herniorrhaphy. Am J Surg 169(1):84–89

Wilson MS, Deans GT, Brough WA (1995) Prospective trial comparing Lichtenstein with laparoscopic tension-free mesh repair of inguinal hernia. Br J Surg 82(2):274–277