- •Table of Contents

- •Copyright

- •Dedication

- •Introduction to the eighth edition

- •Online contents

- •List of Illustrations

- •List of Tables

- •1. Pulmonary anatomy and physiology: The basics

- •Anatomy

- •Physiology

- •Abnormalities in gas exchange

- •Suggested readings

- •2. Presentation of the patient with pulmonary disease

- •Dyspnea

- •Cough

- •Hemoptysis

- •Chest pain

- •Suggested readings

- •3. Evaluation of the patient with pulmonary disease

- •Evaluation on a macroscopic level

- •Evaluation on a microscopic level

- •Assessment on a functional level

- •Suggested readings

- •4. Anatomic and physiologic aspects of airways

- •Structure

- •Function

- •Suggested readings

- •5. Asthma

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Treatment

- •Suggested readings

- •6. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach and assessment

- •Treatment

- •Suggested readings

- •7. Miscellaneous airway diseases

- •Bronchiectasis

- •Cystic fibrosis

- •Upper airway disease

- •Suggested readings

- •8. Anatomic and physiologic aspects of the pulmonary parenchyma

- •Anatomy

- •Physiology

- •Suggested readings

- •9. Overview of diffuse parenchymal lung diseases

- •Pathology

- •Pathogenesis

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Suggested readings

- •10. Diffuse parenchymal lung diseases associated with known etiologic agents

- •Diseases caused by inhaled inorganic dusts

- •Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- •Drug-induced parenchymal lung disease

- •Radiation-induced lung disease

- •Suggested readings

- •11. Diffuse parenchymal lung diseases of unknown etiology

- •Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- •Other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias

- •Pulmonary parenchymal involvement complicating systemic rheumatic disease

- •Sarcoidosis

- •Miscellaneous disorders involving the pulmonary parenchyma

- •Suggested readings

- •12. Anatomic and physiologic aspects of the pulmonary vasculature

- •Anatomy

- •Physiology

- •Suggested readings

- •13. Pulmonary embolism

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic evaluation

- •Treatment

- •Suggested readings

- •14. Pulmonary hypertension

- •Pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic features

- •Specific disorders associated with pulmonary hypertension

- •Suggested readings

- •15. Pleural disease

- •Anatomy

- •Physiology

- •Pleural effusion

- •Pneumothorax

- •Malignant mesothelioma

- •Suggested readings

- •16. Mediastinal disease

- •Anatomic features

- •Mediastinal masses

- •Pneumomediastinum

- •Suggested readings

- •17. Anatomic and physiologic aspects of neural, muscular, and chest wall interactions with the lungs

- •Respiratory control

- •Respiratory muscles

- •Suggested readings

- •18. Disorders of ventilatory control

- •Primary neurologic disease

- •Cheyne-stokes breathing

- •Control abnormalities secondary to lung disease

- •Sleep apnea syndrome

- •Suggested readings

- •19. Disorders of the respiratory pump

- •Neuromuscular disease affecting the muscles of respiration

- •Diaphragmatic disease

- •Disorders affecting the chest wall

- •Suggested readings

- •20. Lung cancer: Etiologic and pathologic aspects

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Suggested readings

- •21. Lung cancer: Clinical aspects

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Principles of therapy

- •Bronchial carcinoid tumors

- •Solitary pulmonary nodule

- •Suggested readings

- •22. Lung defense mechanisms

- •Physical or anatomic factors

- •Antimicrobial peptides

- •Phagocytic and inflammatory cells

- •Adaptive immune responses

- •Failure of respiratory defense mechanisms

- •Augmentation of respiratory defense mechanisms

- •Suggested readings

- •23. Pneumonia

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features and initial diagnosis

- •Therapeutic approach: General principles and antibiotic susceptibility

- •Initial management strategies based on clinical setting of pneumonia

- •Suggested readings

- •24. Bacterial and viral organisms causing pneumonia

- •Bacteria

- •Viruses

- •Intrathoracic complications of pneumonia

- •Respiratory infections associated with bioterrorism

- •Suggested readings

- •25. Tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Definitions

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical manifestations

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Principles of therapy

- •Nontuberculous mycobacteria

- •Suggested readings

- •26. Miscellaneous infections caused by fungi, including Pneumocystis

- •Fungal infections

- •Pneumocystis infection

- •Suggested readings

- •27. Pulmonary complications in the immunocompromised host

- •Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- •Pulmonary complications in non–HIV immunocompromised patients

- •Suggested readings

- •28. Classification and pathophysiologic aspects of respiratory failure

- •Definition of respiratory failure

- •Classification of acute respiratory failure

- •Presentation of gas exchange failure

- •Pathogenesis of gas exchange abnormalities

- •Clinical and therapeutic aspects of hypercapnic/hypoxemic respiratory failure

- •Suggested readings

- •29. Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- •Physiology of fluid movement in alveolar interstitium

- •Etiology

- •Pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Treatment

- •Suggested readings

- •30. Management of respiratory failure

- •Goals and principles underlying supportive therapy

- •Mechanical ventilation

- •Selected aspects of therapy for chronic respiratory failure

- •Suggested readings

- •Index

typical early during the illness, often progressing to multilobar consolidations. Diagnosis is usually accomplished through PCR testing of respiratory secretions (sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage). Urine antigen testing is widely available and highly specific, but only detects L. pneumophila serotype 1. Although this serotype causes most infections worldwide, some regions (especially New Zealand and Australia) have a high prevalence of other serotypes. Drugs of choice for treatment are levofloxacin or azithromycin. Notably, β-lactam antibiotics are not effective in treating this organism.

Chlamydophila pneumoniae

Chlamydophila pneumoniae is an obligate intracellular organism that is recognized in epidemiologic studies as a cause of CAP. The reported incidence ranges from less than 1% to 20%, depending on the series and methods of diagnosis. C. pneumoniae typically causes a mild illness. There are no distinguishing clinical and radiographic features, and the organism is not readily cultured. Diagnosis is rarely made clinically because most patients are treated empirically for CAP without specific testing. In patients who are more severely ill, diagnosis with PCR testing of respiratory secretions can be pursued. Serologic studies can provide retrospective diagnosis, but are not useful for acute diagnosis.

Many other types of bacteria can cause pneumonia. Because all of them cannot be covered in this chapter, the interested reader should consult some of the more detailed publications listed in the Suggested Readings at the end of this chapter.

Viruses

Although viruses are extremely common causes of upper respiratory tract infections, previously they were diagnosed relatively infrequently as a cause of frank pneumonia. Here we focus on two viruses which are common and can be associated with severe disease: SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus.

SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19

In late 2019, SARS-CoV-2, a novel viral pathogen that ultimately resulted in a devastating and widereaching global viral pandemic, was identified. SARS CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is a highly contagious member of the coronavirus family. Since its initial identification, SARS-CoV-2 has undergone a number of mutations, leading to variants that have been called Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and most recently (as of 2022) Omicron. These variants differ to some extent in the likelihood of transmissibility as well as the risk of severe disease.

The spectrum of disease due to SARS-CoV-2 runs from completely asymptomatic to progressive and fatal lung disease. Risk factors for severe disease include older age, obesity, and other comorbid medical conditions. Population data indicated that COVID-19 has disproportionately affected Black, Hispanic, and South Asian individuals in the United States and the United Kingdom. This appears to be related to underlying disparities in the social determinants of health, as early studies which control for these determinants do not find a discrepancy. Although SARS-CoV-2 infection is also associated with many less frequent extrapulmonary manifestations, most notably kidney and cardiac dysfunction and a hypercoagulable state, this discussion will focus solely on the pulmonary manifestations.

SARS-CoV-2 primarily infects cells when the viral spike protein attaches to the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptor. ACE-2 is widely distributed in epithelial and endothelial cells throughout the body, including in the respiratory tract (in nasal mucosa, bronchi, and particularly type II pneumocytes and macrophages). When COVID-19 pneumonia was first recognized, many clinicians noted that patients infected with COVID-19 had much more prominent hypoxemia and relatively more compliant lungs than typical patients who developed the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS, see Chapter 29).

Research has subsequently shown that SARS-CoV-2 caused direct injury by infecting type II pneumocytes and pulmonary vascular endothelial cells at the onset of disease, and hypoxic vasoconstriction (HPVC) appears to be severely impaired. The direct injury to the lung parenchyma and vasculature combined with

the abnormal HPVC leads to hypoxemia because of severe  mismatch early in the disease before the chest x-ray becomes densely consolidated and the lungs become markedly less compliant. Because surfactant is made by the type II pneumocyte, surfactant dysfunction and scattered microatelectasis likely also play an early role.

mismatch early in the disease before the chest x-ray becomes densely consolidated and the lungs become markedly less compliant. Because surfactant is made by the type II pneumocyte, surfactant dysfunction and scattered microatelectasis likely also play an early role.

Patients with COVID-19 pneumonia typically present with fever, cough, shortness of breath, and bilateral pulmonary infiltrates. Loss of smell and/or taste was common with earlier variants but appears to be less frequent with the Omicron variant. A typical chest x-ray in early COVID-19 pneumonia shows diffuse, hazy, nonlobar infiltrates (Fig. 24.4). The diagnosis is confirmed by nasal swab PCR or antigen testing.

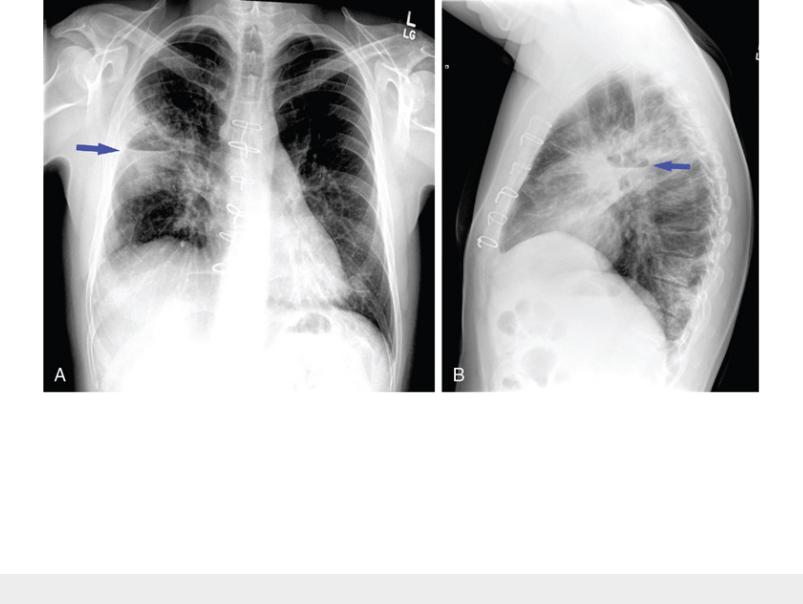

FIGURE 24.4 Posteroanterior chest radiograph (A) and chest CT scan (B) of a

patient with COVID-19 pneumonia showing a typical pattern of bilateral, diffuse,

and predominantly peripheral ground-glass opacities with some areas of more dense

consolidation. Source: (Courtesy of Dr. Laura Avery.)

Treatment depends on the timing and severity of disease. Although the information provided here is current as of 2022, it will likely change as our understanding of the disease is continually evolving. Younger, healthy individuals usually require no treatment. In individuals at risk for severe disease, early treatment with monoclonal antibodies directed at SARS-CoV-2 or oral antiviral drugs (combination therapy with nirmatrelvir-ritonavir) are indicated. The antiviral remdesivir is also an option, but is only available intravenously and thus is typically reserved for hospitalized patients.

In severely ill patients, it is recognized that the host inflammatory and cytokine response in addition to the virus itself is responsible for many of the manifestations. Thus, for patients hospitalized with COVID19, medications which target the inflammatory and/or cytokine response are often used, including dexamethasone (a corticosteroid), tocilizumab (an antibody against the IL-6 receptor), and baricitinib (a JAK protein inhibitor).

Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 are available and provide marked protection from severe disease. These vaccines are indicated and approved for all individuals aged 6 months and older. Notably, some of

Данная книга находится в списке для перевода на русский язык сайта https://meduniver.com/

these vaccines have used a novel approach involving mRNA that encodes for a target protein on the virus. Administration of the specific mRNA leads to the individual producing and developing an immune response to the target protein.

Several other coronaviruses have caused much more limited epidemics of severe viral pneumonia in recent years. An outbreak of a highly contagious and highly lethal pneumonia was reported in 2003 in East Asia and Canada. The outbreak, termed severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), was attributed to a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV) that may have evolved from a type normally found in the civet (a weasellike mammal found in Chinese markets). In 2012, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus (MERS-CoV) caused an outbreak of severe pneumonia with a nearly 75% mortality rate. The causative agent is related to a virus that normally infects camels, and most cases have been traced to initial exposures in the Arabian Peninsula.

Influenza

Two types of influenza virus cause significant respiratory disease, influenza A and influenza B. Epidemics of influenza occur almost every year, and the severity depends on the viral antigenic characteristics, which change regularly. The most notable pandemic in the modern era was the 1918 influenza pandemic, which is estimated to have resulted in 50 to 100 million deaths, or 3% to 5% of the world’s population. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence of influenza infections has decreased, likely due to changes in behavior such as mask-wearing and social distancing, which protect from both SARS- CoV-2 and influenza.

Clinically, influenza is usually characterized by the abrupt onset of fever, chills, and malaise. Muscle aches (myalgias) are prominent. Most patients do not develop pneumonia; however, when present, pneumonia may be a primary influenza pneumonia or due to secondary bacterial infection. Primary influenza appears as diffuse bilateral reticular or reticulonodular infiltrates. The presence of more lobar consolidations should raise concern for complicating bacterial infection, especially with S. pneumoniae or S. aureus. Diagnosis is made by PCR testing of nasopharyngeal specimens.

Oseltamivir is the preferred treatment for influenza and is shown to be effective in reducing the duration and severity of disease if given within 48 hours of symptom onset. Several types of influenza vaccines are formulated every year according to the prevalent and anticipated strains, and annual vaccination is recommended for all adults and children aged 6 months and older.

Other viruses

Outbreaks of pneumonia caused by adenovirus also are well described, particularly among military recruits. Hantavirus, a relatively rare cause of a fulminant and often lethal pneumonia, was first described in the southwest United States, but cases in other locations have also been recognized. Related viruses are found in rodents and were previously described as a cause of fever, hemorrhage, and acute renal failure in other parts of the world.

Intrathoracic complications of pneumonia

As part of the discussion of pneumonia, two specific intrathoracic complications of pneumonia—lung abscess and empyema—are briefly considered because they represent important clinical sequelae.

Lung abscess

A lung abscess, like an abscess elsewhere, represents a localized collection of pus. In the lung, abscesses generally result from tissue destruction complicating a pneumonia. The abscess contents are primarily

neutrophils, often with collections of bacterial organisms. When antibiotics have been administered, organisms may no longer be culturable from the abscess cavity.

Etiologic agents associated with formation of a lung abscess are generally those bacteria that cause significant tissue necrosis. Most commonly, anaerobic organisms are responsible, suggesting that aspiration of oropharyngeal contents is the predisposing event. However, aerobic organisms, such as Staphylococcus or enteric Gram-negative rods, can also cause significant tissue destruction with cavitation of a region of lung parenchyma and abscess formation (Fig. 24.5). Right-sided endocarditis can be associated with multiple lung abscesses, as small infectious particles are released into the blood from the infected valve and lodge in the pulmonary parenchyma.

FIGURE 24.5 Posteroanterior (A) and lateral (B) chest radiographs showing a

cavitary lung abscess with an air-fluid level (arrows) in the right upper lobe. Note

the sternal wires. The patient had a history of intravenous drug use and had

undergone tricuspid valve surgery for endocarditis. Source: (Courtesy of Dr. Laura

Avery.)

Anaerobic bacteria are the agents most frequently responsible for lung abscesses.

Treatment of a lung abscess involves antibiotic therapy, given for longer than for an uncomplicated pneumonia. Although abscesses elsewhere in the body are drained by surgical incision or catheter placement, lung abscesses generally drain through the tracheobronchial tree, and surgical intervention or placement of a drainage catheter is needed only rarely.

Empyema

When pneumonia extends to the pleural surface, the inflammatory process eventually may lead to

Данная книга находится в списке для перевода на русский язык сайта https://meduniver.com/