- •Table of Contents

- •Copyright

- •Dedication

- •Introduction to the eighth edition

- •Online contents

- •List of Illustrations

- •List of Tables

- •1. Pulmonary anatomy and physiology: The basics

- •Anatomy

- •Physiology

- •Abnormalities in gas exchange

- •Suggested readings

- •2. Presentation of the patient with pulmonary disease

- •Dyspnea

- •Cough

- •Hemoptysis

- •Chest pain

- •Suggested readings

- •3. Evaluation of the patient with pulmonary disease

- •Evaluation on a macroscopic level

- •Evaluation on a microscopic level

- •Assessment on a functional level

- •Suggested readings

- •4. Anatomic and physiologic aspects of airways

- •Structure

- •Function

- •Suggested readings

- •5. Asthma

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Treatment

- •Suggested readings

- •6. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach and assessment

- •Treatment

- •Suggested readings

- •7. Miscellaneous airway diseases

- •Bronchiectasis

- •Cystic fibrosis

- •Upper airway disease

- •Suggested readings

- •8. Anatomic and physiologic aspects of the pulmonary parenchyma

- •Anatomy

- •Physiology

- •Suggested readings

- •9. Overview of diffuse parenchymal lung diseases

- •Pathology

- •Pathogenesis

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Suggested readings

- •10. Diffuse parenchymal lung diseases associated with known etiologic agents

- •Diseases caused by inhaled inorganic dusts

- •Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- •Drug-induced parenchymal lung disease

- •Radiation-induced lung disease

- •Suggested readings

- •11. Diffuse parenchymal lung diseases of unknown etiology

- •Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- •Other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias

- •Pulmonary parenchymal involvement complicating systemic rheumatic disease

- •Sarcoidosis

- •Miscellaneous disorders involving the pulmonary parenchyma

- •Suggested readings

- •12. Anatomic and physiologic aspects of the pulmonary vasculature

- •Anatomy

- •Physiology

- •Suggested readings

- •13. Pulmonary embolism

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic evaluation

- •Treatment

- •Suggested readings

- •14. Pulmonary hypertension

- •Pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic features

- •Specific disorders associated with pulmonary hypertension

- •Suggested readings

- •15. Pleural disease

- •Anatomy

- •Physiology

- •Pleural effusion

- •Pneumothorax

- •Malignant mesothelioma

- •Suggested readings

- •16. Mediastinal disease

- •Anatomic features

- •Mediastinal masses

- •Pneumomediastinum

- •Suggested readings

- •17. Anatomic and physiologic aspects of neural, muscular, and chest wall interactions with the lungs

- •Respiratory control

- •Respiratory muscles

- •Suggested readings

- •18. Disorders of ventilatory control

- •Primary neurologic disease

- •Cheyne-stokes breathing

- •Control abnormalities secondary to lung disease

- •Sleep apnea syndrome

- •Suggested readings

- •19. Disorders of the respiratory pump

- •Neuromuscular disease affecting the muscles of respiration

- •Diaphragmatic disease

- •Disorders affecting the chest wall

- •Suggested readings

- •20. Lung cancer: Etiologic and pathologic aspects

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Suggested readings

- •21. Lung cancer: Clinical aspects

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Principles of therapy

- •Bronchial carcinoid tumors

- •Solitary pulmonary nodule

- •Suggested readings

- •22. Lung defense mechanisms

- •Physical or anatomic factors

- •Antimicrobial peptides

- •Phagocytic and inflammatory cells

- •Adaptive immune responses

- •Failure of respiratory defense mechanisms

- •Augmentation of respiratory defense mechanisms

- •Suggested readings

- •23. Pneumonia

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features and initial diagnosis

- •Therapeutic approach: General principles and antibiotic susceptibility

- •Initial management strategies based on clinical setting of pneumonia

- •Suggested readings

- •24. Bacterial and viral organisms causing pneumonia

- •Bacteria

- •Viruses

- •Intrathoracic complications of pneumonia

- •Respiratory infections associated with bioterrorism

- •Suggested readings

- •25. Tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Definitions

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical manifestations

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Principles of therapy

- •Nontuberculous mycobacteria

- •Suggested readings

- •26. Miscellaneous infections caused by fungi, including Pneumocystis

- •Fungal infections

- •Pneumocystis infection

- •Suggested readings

- •27. Pulmonary complications in the immunocompromised host

- •Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- •Pulmonary complications in non–HIV immunocompromised patients

- •Suggested readings

- •28. Classification and pathophysiologic aspects of respiratory failure

- •Definition of respiratory failure

- •Classification of acute respiratory failure

- •Presentation of gas exchange failure

- •Pathogenesis of gas exchange abnormalities

- •Clinical and therapeutic aspects of hypercapnic/hypoxemic respiratory failure

- •Suggested readings

- •29. Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- •Physiology of fluid movement in alveolar interstitium

- •Etiology

- •Pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Treatment

- •Suggested readings

- •30. Management of respiratory failure

- •Goals and principles underlying supportive therapy

- •Mechanical ventilation

- •Selected aspects of therapy for chronic respiratory failure

- •Suggested readings

- •Index

24: Bacterial and viral organisms causing pneumonia

OUTLINE

Bacteria, 287

Streptococcus Pneumoniae, 287

Staphylococcus Aureus, 288

Gram-Negative Organisms, 289

Mycoplasma, 290

Legionella Pneumophila, 290

Chlamydophila Pneumoniae, 291

Viruses, 291

SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19, 291

Influenza, 293

Other Viruses, 293

Intrathoracic Complications of Pneumonia, 293

Lung Abscess, 293

Empyema, 294

Respiratory Infections Associated with Bioterrorism, 295

Anthrax, 295

Plague, 295

Tularemia, 296

In this chapter, we expand upon the general discussion of pneumonia in Chapter 23 to consider some of the specific and common responsible organisms. The most clinically relevant pathogens are addressed here, with the focus on individual etiologic agents and characteristic features of each that are particularly useful to the clinician. Importantly, as discussed in Chapter 23, the clinician usually must decide about a

treatment regimen before knowing which specific organism is causing disease. This decision is based on patient characteristics and whether the infection was acquired in the community (community-acquired pneumonia [CAP]) or in the hospital or other healthcare setting (hospital-acquired pneumonia [HAP]). Even when extensive testing protocols are used for patients requiring hospital admission, the specific pathogen is identified in fewer than 60% of cases. Lung abscess and empyema, two of the more common complications of pneumonia, are also addressed.

The chapter concludes with a brief discussion of several infections that are relevant as the threat of bioterrorism has emerged. In addition to reviewing inhalational anthrax, the chapter briefly describes two other organisms considered to be of concern as potential weapons of bioterrorism: Yersinia pestis (the cause of plague) and Francisella tularensis (the cause of tularemia).

Bacteria

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Of the bacteria, the organism most frequently associated with pneumonia is Streptococcus pneumoniae; in common parlance, it is often called pneumococcus. It has been estimated that in adults, approximately one-half of all pneumonias serious enough to require hospitalization are caused by this organism. S. pneumoniae, a normal inhabitant of the oropharynx in a large proportion of adults and children, is a Gram-positive coccus typically seen in pairs, or diplococci. Pneumococcal pneumonia is the most common cause of CAP and frequently occurs following a viral upper respiratory tract infection. The organism has a polysaccharide capsule that interferes with immune recognition and phagocytosis; this is an important factor in its virulence. There are many different antigenic types of capsular polysaccharide, and for host defense cells to phagocytize the organism, antibody against the particular capsular type must be present. Antibodies contributing in this way to the phagocytic process are called opsonins (see Chapter 22).

In pneumococcal pneumonia, onset of the clinical illness is often abrupt, with the sudden development of shaking chills and high fever. The cough may be productive of yellow, green, or blood-tinged (rustycolored) sputum. Before the development of pneumonia, patients often have experienced a viral upper respiratory tract infection, which is an important predisposing feature. Chest radiographs commonly show a dense lobar infiltrate, although more patchy patterns are also seen (Fig. 24.1).

Данная книга находится в списке для перевода на русский язык сайта https://meduniver.com/

FIGURE 24.1 Posteroanterior (A) and lateral (B) chest radiographs show lobar

pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae affecting most of the right lower

lobe (RLL). In (A), visualization of the right diaphragm has been lost because it is

adjacent to consolidated rather than air-containing lung (the “silhouette sign”). In

(B), the arrow points to the right lung major fissure, and the arrowhead points to

increased opacity over the spine posteriorly (often called the “spine sign”).

Source: (Courtesy of Dr. Laura Avery.)

Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) is the most common cause of bacterial pneumonia. The polysaccharide capsule is an important factor in its virulence.

Typically, outpatients with clinical findings and a chest x-ray consistent with suspected pneumococcal pneumonia are treated empirically with antibiotics appropriate for a CAP, and do not require further testing. Adult patients who are hospitalized should have sputum Gram stain and culture, blood cultures, and a urine pneumococcal antigen test, which detects polysaccharide components of the cell wall. Notably, there is a high rate of false-positive urine antigen tests in healthy children due to nasopharyngeal colonization by S. pneumoniae; therefore, this test is not recommended in children. Definitive diagnosis of pneumococcal infection requires culture of the organism from blood or pleural fluid, which are both normally sterile. If the pneumococcus is identified, treatment is with a β-lactam antibiotic if possible. Vaccines have been available against pneumococcus for many years and have been improved more recently by conjugating pneumococcal polysaccharides to proteins, which produces a more robust immune response. Vaccination is indicated for all adults older than 65 years and for individuals with a specified chronic medical condition or risk factor.

Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is another Gram-positive coccus, but is found in clusters when examined

microscopically. Three major settings in which this organism is seen as a cause of pneumonia are as follows: (1) as a secondary complication of respiratory tract infection with the influenza virus; (2) in the hospitalized patient, who often has some impairment of host defense mechanisms and whose oropharynx has been colonized by Staphylococcus; and (3) as a complication of widespread dissemination of staphylococcal organisms through the bloodstream.

S. aureus is an uncommon cause of CAP, but accounts for up to 30% of nosocomial pneumonia cases. Notably, community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is a significant problem, and antibiotic choice should target MRSA if it is suspected. Patients with S. aureus are typically acutely ill with high fever and may develop rapid deterioration. Because S. aureus can cause a necrotizing infection, purulent bloody sputum is often seen.

When S. aureus pneumonia is suspected, because of the propensity of the organism to spread to the lung from a bloodstream infection, a search for a nonpulmonary site (especially endocarditis) is indicated. Chest radiographs typically show a bronchopneumonia pattern with a patchy distribution; however, a lobar infiltrate may also be seen (Fig. 24.2). When the pneumonia is due to hematogenous spread, multiple small abscesses may be present.

FIGURE 24.2 Posteroanterior (A) and lateral (B) chest radiographs show a patchy

lobar pneumonia in the lingular segments of the left upper lobe due to

Staphylococcus aureus. In (A), the consolidation in the lingula is adjacent to the

heart and has caused loss of the left heart border (another example of a silhouette

sign, as also shown in Fig. 24.1). Source: (Courtesy of Dr. Laura Avery.)

Gram-negative organisms

Many Gram-negative organisms are potential causes of pneumonia, but only a few of the most important examples are mentioned here. Haemophilus influenzae, a small coccobacillary Gram-negative organism,

Данная книга находится в списке для перевода на русский язык сайта https://meduniver.com/

is often found in the nasopharynx of normal individuals and in the lower airways of patients with COPD. It can cause pneumonia in children and adults—the latter often with underlying COPD as a predisposing factor. Klebsiella pneumoniae, a relatively large Gram-negative rod normally found in the gastrointestinal tract, is most associated with pneumonia in the setting of an underlying alcohol use disorder. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, found in a variety of environmental sources (including the hospital environment), is seen primarily in patients who are debilitated, hospitalized, and often previously treated with antibiotics. P. aeruginosa is also a very common cause of respiratory tract infection in patients with underlying bronchiectasis or cystic fibrosis.

Factors predisposing to oropharyngeal colonization and pneumonia with Gram-negative organisms:

1.Hospitalization or residence in a chronic care facility

2.Underlying disease and compromised host defenses

3.Recent antibiotic therapy

The bacterial flora normally present in the mouth are potential etiologic agents in the development of pneumonia. A multitude of organisms (both Gram-positive and Gram-negative) that favor or require anaerobic conditions for growth are the major organisms comprising mouth flora. The most common predisposing factor for anaerobic pneumonia is the aspiration of secretions from the oropharynx into the tracheobronchial tree, especially in patients with poor dentition or gum disease because of the larger burden of organisms in their oral cavities. Patients with impaired consciousness (e.g., as a result of coma, alcohol or drug ingestion, or seizures) and those with difficulty swallowing (e.g., as a result of stroke or diseases causing muscle weakness) are prone to aspirate and are at greatest risk for pneumonia caused by anaerobic or mixed mouth organisms.

Anaerobes normally found in the oropharynx are a frequent cause of aspiration pneumonia.

In some settings, such as prolonged hospitalization or recent use of antibiotics, the type of bacteria residing in the oropharynx may change. Specifically, aerobic Gram-negative bacilli and S. aureus are more likely to colonize the oropharynx, and any subsequent pneumonia resulting from aspiration of oropharyngeal contents may include these aerobic organisms as part of the process.

Mycoplasma

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a common respiratory pathogen, especially in young adults. It usually causes upper respiratory tract infections or bronchitis, but may also cause pneumonia. Some of the smallest freeliving organisms yet identified, mycoplasmas are similar in size to large viruses, and unlike other bacteria, do not possess a rigid cell wall. This feature is clinically important because the lack of a cell wall means that Mycoplasma does not stain with a Gram stain and is not susceptible to antibiotics that inhibit cell wall synthesis (e.g., β-lactams). These organisms are now recognized as a common cause of pneumonia and are perhaps responsible for 10% to 20% of all cases.

Pneumonia due to Mycoplasma occurs most frequently in young adults but is not limited to this age group. The pneumonia is generally acquired in the community—that is, by previously healthy, nonhospitalized individuals—and may occur in either isolated cases or localized outbreaks. Patients are typically only mildly ill, leading to the lay term of “walking pneumonia” when referring to pneumonia due to Mycoplasma.

Symptoms include a low-grade fever and a prominent cough, with or without sputum production. The chest x-ray typically shows reticulonodular infiltrates and/or patchy opacities (Fig. 24.3); however, it may be remarkably clear, especially in early disease. As with other CAPs in individuals who do not require hospitalization, specific diagnostic testing is not routinely recommended. If specific testing is needed, a Mycoplasma PCR test on respiratory secretions can be performed.

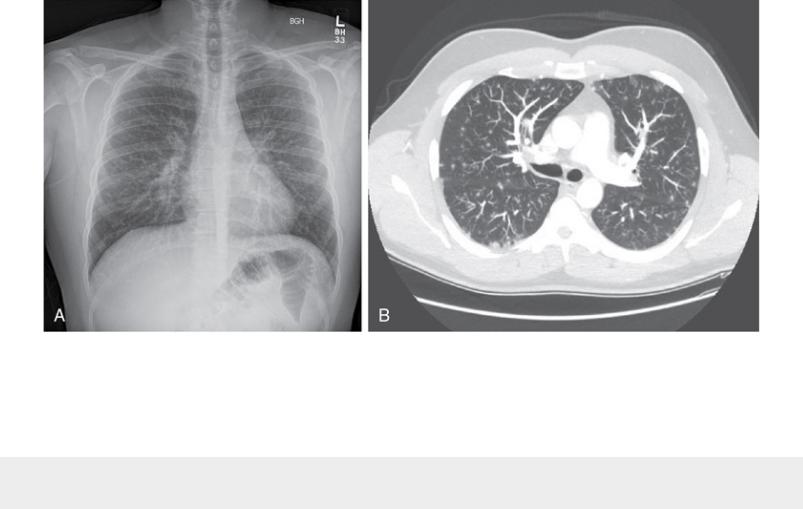

FIGURE 24.3 Posteroanterior chest radiograph (A) and chest CT scan (B) of a

patient with Mycoplasma pneumonia. Note patchy opacities throughout both lungs.

Source: (Courtesy of Dr. Laura Avery.)

Mycoplasma, one of the smallest known free-living organisms, is a frequent cause of pneumonia with relatively mild symptoms in young adults.

Legionella pneumophila

Legionella pneumophila is an important cause of serious pneumonia occurring in epidemics as well as in isolated, sporadic cases. It is estimated to account for up to 10% of cases of CAP, and primarily affects older individuals and those with prior impairment of respiratory defense mechanisms. It also occurs as a sporadic cause of nosocomial pneumonia and is linked to the presence of the organisms in facility water supplies.

L. pneumophila was first identified as the cause of a mysterious outbreak of pneumonia in 1976 affecting American Legion members at a convention in Philadelphia. Thus, pneumonia due to L. pneumophila is often labeled “Legionnaires disease.” Since then, it has been retrospectively recognized as the cause of several prior outbreaks of unexplained pneumonia. Although the organism is technically a Gram-negative bacillus, it is poorly visualized by conventional staining methods and is not seen on Gram stain.

Clinically, patients present with fever, cough, and shortness of breath, and can be quite ill. Extrapulmonary manifestations, including gastrointestinal symptoms, hyponatremia, and liver function test abnormalities, are common and can be a clue to etiology. Radiographically, patchy unilobar infiltrates are

Данная книга находится в списке для перевода на русский язык сайта https://meduniver.com/