Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Thomas R., Connelly J., Burke C. - 100 cases in radiology - 2012

.pdf

ANSWER 18

Headache is a common problem, often assessed in general practice and often associated with tumours by patients. The annual incidence of brain tumours is about 10 per 100 000 per year whereas up to 4000 per 100 000 GP consultations are for headache, so some discrimination has to be used to avoid imaging every patient.

If you see papilloedema then red flags are not required, urgent investigation is mandatory, after checking your records for previous investigation – very occasionally it is idiopathic and chronic. More commonly, fundoscopy is not performed well enough to see changes. Other red flags include:

•systemic symptoms (e.g. neck stiffness) or secondary risk factors (e.g. cancer, HIV, thrombosis);

•neurological symptoms or signs;

•onset (e.g. thunderclap headache);

•new progressive or unilateral headache in older patients (consider temporal arteritis);

•previous headache history changing pattern;

•triggered headache (e.g. cough, sneeze, straining).

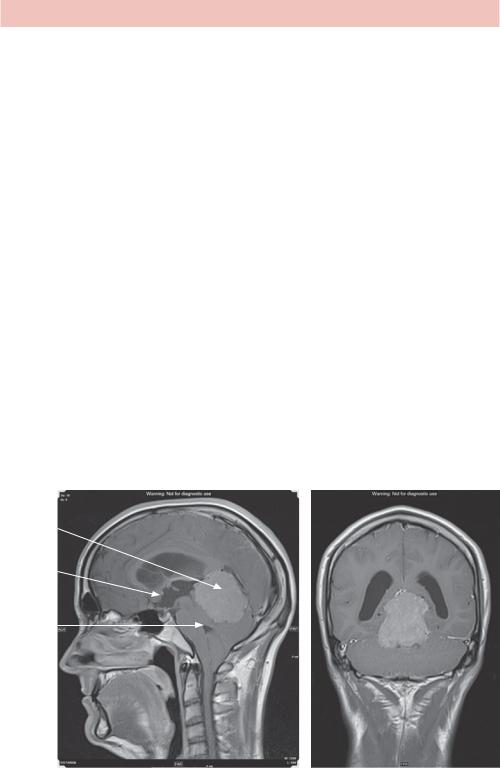

The CT shows a large midline mass in the region of the pineal gland extending into the subtentorial region, displacing the cerebellar vermis and hemispheres inferiorly and compressing the aqueduct and fourth ventricle. There is dilatation of the lateral and third ventricles but undilated fourth ventricle and basal cisterns in keeping with obstructive hydrocephalus.

The next step is to characterize the midline lesion using magnetic resonance (MR) (Figure 18.2). This confirms hydrocephalus caused by a pineal fossa or tectal plate mass with evidence of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the periventricular tissue, suggesting the obstruction is acute. The lesion may be a pineoblastoma.

Mass

3rd ventricle

4th ventricle

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 18.2 (a) Coronal and (b) midline sagittal T1 MR sequence images after gadolinium contrast.

52

Hydrocephalus appears on scans as dilated CSF spaces and can be caused by obstruction, as in this case. Communicating hydrocephalus occurs in the absence of obstruction due to overproduction of CSF (e.g. tumour), defective absorption of CSF (most common, e.g. after haemorrhage) or venous drainage insufficiency. Normal pressure hydrocephalus occurs in older patients characterized by dilatation but no elevation of CSF pressure at lumbar puncture and may be caused by intermittent intracranial hypertension.

This patient requires referral to a neurosurgical centre as the hydrocephalus requires acute treatment with a shunt, as well as treatment planning for the underlying tumour.

KEY POINTS

•Headache is a common symptom and is only rarely caused by a brain tumour.

•Hydrocephalus can be acute or chronic, communicating or obstructive.

•CT is the initial investigation for acute neurological problems to check for haemorrhage, hydrocephalus and presence of mass lesions.

53

This page intentionally left blank

CASE 19: PERSISTENT COUGH

History

A 65-year-old woman with a persistent cough comes to see you in general practice. She says that the cough has been present for months but that it has got worse in the last week with associated coryzal symptoms. There is no history of haemoptysis, chest pain or weight loss. She does not have asthma and is on medication for high blood pressure and high cholesterol. She has a 30 pack-year smoking history, although she gave up 2 years ago.

Examination

There is no abnormality on examination of the respiratory system. Temperature and pulse are normal; her blood pressure is 136/82. There is no significant neck lymphadenopathy or tonsillar enlargement.

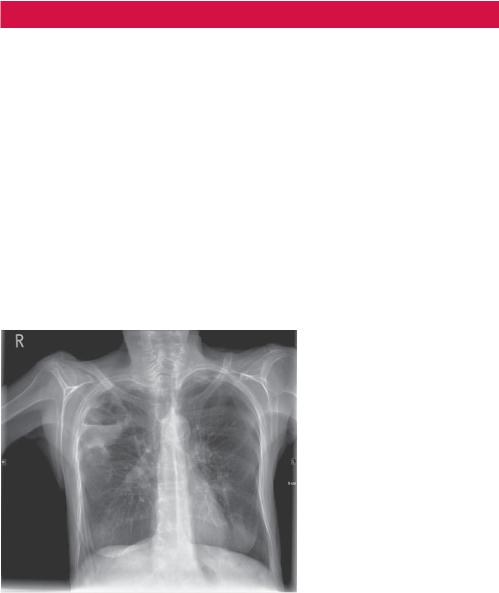

You consider the diagnosis of an acute upper respiratory tract infection with a background persistent cough. The cough has not been investigated before and you explain to the patient that you will arrange a chest X-ray (Figure 19.1) but that antibiotics do not seem appropriate currently.

Figure 19.1 Posterior–anterior chest radiograph.

Questions

•What does the radiograph show?

•What are the most likely diagnoses?

•What is the next step?

55

ANSWER 19

The radiograph shows a single spiculated mass in the right mid zone. No significant hilar or mediastinal widening is seen.

The differential diagnosis for a single pulmonary mass includes primary or secondary carcinoma, hamartoma (especially if fat and calcification can be identified), pneumonia or arteriovenous malformation. The patient’s age, smoking history and chronic cough are red flags for considering carcinoma.

The next step is rapid referral of the patient to chest clinic with a preceding staging computed tomography (CT) scan. Most hospitals have a streamlined process for the radiology department to flag up the patient to the relevant specialist clinic if cancer is suspected, in anticipation of an urgent general practitioner (GP) referral.

The diagnosis of non-small cell lung carcinoma and stage of disease was confirmed by biopsy and positron emission tomography (PET) scan that confirmed T2a (<5 cm) N0 M0 (no affected lymph nodes or metastases) staging. The tumour was removed with the right upper lobe (lobectomy).

The post-lobectomy radiograph (Figure 19.2a) shows signs of loss of right lung volume with elevation of the right hemidiaphragm and hilum but no significant right rib space narrowing.

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 19.2 (a) Postand (b) pre-operative chest radiographs with the lesion marked with an arrow.

GPs have access to many imaging modalities at their local hospital, although plain radiographs and ultrasound are the most used. They receive copies of the image reports, typically within a week, but are not able to view the images. The Royal College of Radiologists has produced referral guidelines.1

Chronic cough is a common GP presentation. The British Thoracic Society has produced guidelines on how to manage chronic cough,2 a chest radiograph being one of the first steps. Subsequent imaging depends on the diagnosis and whether imaging is likely to be helpful in management.

56

KEY POINTS

•Pulmonary lobectomy results in loss of volume with possible elevation of the hemidiaphragm and hilum, rib crowding or little or no volume change with hyperexpansion of the residual lobes with associated increased translucency.

•GPs have access to imaging modalities but typically do not have access to the images and therefore it is important that the request states the clinical context and question and the report provides an answer.

Reference

1.Royal College of Radiologists (2007) Making the Best Use of Clinical Radiology Services, 6th edn. London: Royal College of Radiologists.

2.British Thoracic Society (2006) Recommendations for the Management of Cough in Adults. Produced by British Thoracic Society Cough Guideline Group; a sub-committee of the Standards of Care Committee of the British Thoracic Society. Thorax 61(suppl 1): i1–i24.

57

This page intentionally left blank

CASE 20: CHEST PAIN AND DYSPNOEA

History

This 66-year-old woman was referred to the accident and emergency department by her general practitioner (GP) with a 2 week history of dyspnoea, cough and fever that has been worsening and an unclear history of new onset pleuritic chest pain. There is also a history of a chronic pressure sore, type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure treated with appropriate medication. The GP had treated her for a few days with antibiotics initially with little effect.

Examination

Her temperature is 39.3°C, pulse 104/minute, oxygen saturation 89 per cent breathing air and there appears to be a right ventricular heave. There are coarse lung sounds in the right upper zone posteriorly. The abdomen is soft and non-tender. The left hip is painful but demonstrates normal range of movement and weight bearing. There is a mild degree of peripheral sensory neuropathy but the legs are otherwise normal.

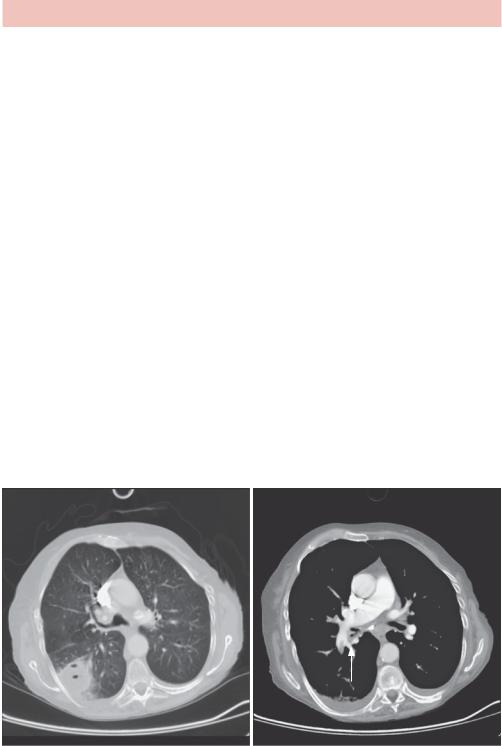

You arrange tests including a chest radiograph (Figure 20.1).

Figure 20.1 Chest radiograph.

Questions

•What does the chest radiograph show?

•What are possible causes of the abnormality?

59

ANSWER 20

There is one and possibly a second circular cavitating lesion in the right upper zone that contains an air–fluid level and has a thin wall superiorly. There is bilateral apical thickening. The hila appear normal and the heart is not enlarged. A displaced old fracture of the left clavicle is noted.

There are multiple causes of cavities in the lung and features that help decide on likely differential diagnoses include the clinical context, number of lesions, wall thickness, appearance of contents (if any), position and presence of enlarged lymph nodes.

In terms of categories, cavities may form due to:

•infection, such as Staphylococcus (frequently multiple), Klebsiella, tuberculosis (frequently associated with fibrosis) and aspiration (these cavities are usually thick walled and may contain fluid levels);

•neoplasm, such as bronchogenic carcinoma (particularly squamous cell carcinoma, SCC), metastases such as SCC, colon and sarcoma, Hodgkin’s disease (with lymphadenopathy), often with thick walls;

•vascular infarction that may cavitate or become infected and cavitate;

•trauma, either the result of a haematoma or formation of a traumatic lung cyst;

•abnormal lung – infected emphysematous bulla;

•cavitating nodular vasculitic disease such as Wegener’s granulomatosis, rheumatoid arthritis and occasionally granulomatous disease such as sarcoidosis, which all frequently have multiple cavities.

Given the patient’s tachycardia, ventricular heave and hypoxia it is also important to consider cardiac causes and possible pulmonary embolism. A computed tomography (CT) pulmonary angiogram was arranged (Figure 20.2a,b).

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 20.2 CT pulmonary angiogram showing a right lower lobe fluid-filled cavity (a) and, on the slice just inferior (b), a pulmonary embolus in the right lower lobe pulmonary artery (white arrow).

60

The most likely differential diagnoses are cavitation and infection secondary to an embolus or a cavitating lung malignancy with secondary pulmonary embolus. The short history and fever suggest infection and the subsequent course showed that the former diagnosis was correct.

KEY POINTS

•Position, number of lesions, wall thickness and contents may be helpful in determining the cause of lung cavities.

•Cavities are potential sites for secondary infection.

61