Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Thomas R., Connelly J., Burke C. - 100 cases in radiology - 2012

.pdf

ANSWER 79

This 14-year-old girl has sustained a hyperflexion ‘teardrop’ fracture of C7 which is also crushed. There is wedging of the vertebral body with retropulsion of the posterior fragment into the spinal canal. This can be seen on both the initial lateral radiograph Figure 79.1 and more clearly on the sagittal CT image of the cervical spine (Figure 79.2). A flexion teardrop fracture occurs when flexion of the spine, along with vertical axial compression, causes a fracture of the anterior–inferior aspect of the vertebral body. This fragment is displaced anteriorly and resembles a teardrop.

For this fragment to be produced significant posterior ligamentous disruption must occur and as the fragment displaces anteriorly, a significant degree of anterior ligamentous disruption must take place.

This example demonstrates a flexion injury, however, cervical spine injuries are classified according to several other mechanisms of injury in addition to flexion, including flexion–rotation, extension, extension–rotation, vertical compression, lateral flexion and mechanisms resulting in odontoid (C2) fractures and atlanto-occipital dislocation.

The cervical spine should be seen as three distinct columns:

•Anterior column: This is composed of the anterior longitudinal ligament and the anterior two-thirds of the vertebral bodies, the annulus fibrosus and the intervertebral discs.

•Middle column: This is composed of the posterior longitudinal ligament and the posterior one-third of the vertebral bodies, the annulus and intervertebral discs.

•Posterior column: This contains all of the bony elements formed by the pedicles, transverse processes, articulating facets, laminae and spinous processes.

If one column is disrupted, other columns may provide sufficient stability to prevent spinal cord injury. If two columns are disrupted, the spine may move as separate units, increasing the likelihood of spinal cord injury.

This fracture is important to recognize as it is an unstable type of cervical spine fracture involving disruption of all three spinal columns, making this an extremely unstable fracture that frequently is associated with spinal cord injury.

The girl in this case was referred to the spinal service and initially managed with the application of traction with cervical tongs, but later underwent a C7 corpectomy and fusion (Figure 79.3).

Figure 79.3 Lateral radiograph post surgery showing C7 corpectomy and fusion.

222

When interpreting lateral cervical views, first you should check the technical adequacy of the radiograph, which must show all seven vertebral bodies and the cervicothoracic junction. Next, look for soft tissue changes in predental and prevertebral spaces (if the prevertebral space is widened at any level, a haematoma secondary to a fracture is likely). At the level of C2, prevertebral space should not exceed 7 mm and at the level of C6 and below, where the prevertebral space is widened by the presence of the oesophagus and cricopharyngeal muscle, no more than 22 mm in adults/14 mm in children younger than 15 years.

Then check the alignment of the cervical spine by following three imaginary contour lines:

•The first line connects the anterior margins of all the vertebrae and is referred to as the anterior contour line. It is clearly disrupted in Figure 79.1.

•The second line should connect the posterior aspect of all vertebrae in a similar way and is referred to as the posterior contour line. This is also disrupted in Figure 79.1.

•The third line should connect the bases of the spinous processes. This is referred to as the spinolaminar line.

KEY POINTS

•Approximately 85–90 per cent of cervical spine injuries are evident in lateral view.

•An acceptable lateral view must show all seven vertebral bodies and the cervicothoracic junction.

•It is important to check the alignment of cervical spine by following three imaginary contour lines.

•Soft tissue changes in predental and prevertebral spaces should always be looked for.

223

This page intentionally left blank

CASE 80: ABDOMINAL PAIN AND DIARRHOEA IN A 28-YEAR-OLD

WOMAN

History

You are asked to review the abdominal radiograph of a 28-year-old woman who has presented to the accident and emergency department with worsening abdominal pain and diarrhoea. She is known to have a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis and, despite occasional disease exacerbations as a teenager, she has been symptom free for 5 years.

Over the last 2 days she has been complaining of generalized aching abdominal pain. This is associated with diarrhoea that is increasing in frequency and yesterday she opened her bowels nine times. Overnight she was unable to control her loose motions and noticed fresh blood with streaks of pus within the stool. She denies weight loss but gives a history of feeling very lethargic.

She attended the accident and emergency department worried about an acute attack of ulcerative colitis and was found to be tachycardic but normotensive on examination. Her abdomen was distended but not peritonitic, and she reported pain on deep palpation, most marked within the left upper quadrant. Her blood results suggest a degree of renal impairment and dehydration, with a slightly elevated white cell count but normal haemoglobin.

Examination

As part of the initial investigations an abdominal radiograph was performed (Figure 80.1).

Figure 80.1 Abdominal radiograph.

Questions

•What does the abdominal radiograph demonstrate?

•What further imaging is recommended?

•Is there a differential diagnosis for these appearances?

225

ANSWER 80

This is an anterior–posterior abdominal radiograph of an adult female. There is gross abnormality of the large bowel with widespread dilatation most marked at the splenic flexure, where the maximal bowel diameter measures 10.3 cm (normal large bowel diameter <6 cm). There is abnormal thickening and ‘thumbprinting’ of the colonic wall with loss of normal haustrations due to mucosal oedema. There is no evidence of small bowel involvement and no characteristic appearances of ‘Rigler’s sign’ (see below) to suggest extraluminal free gas related to bowel perforation. The appearances are consistent with colitis with bowel dilatation, in keeping with toxic megacolon. Urgent surgical opinion should be sought and clinical correlation advised since perforation is a significant risk.

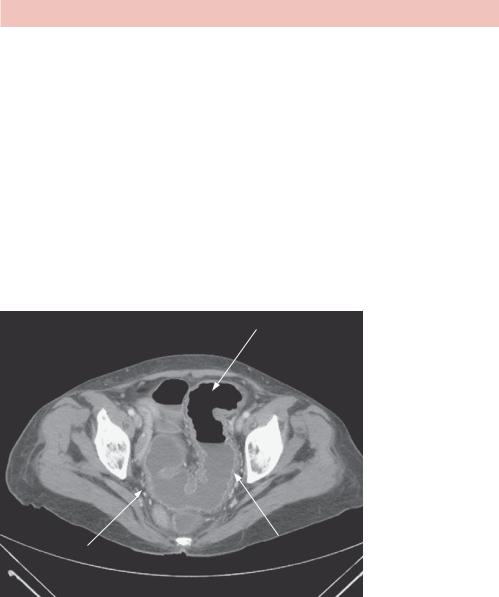

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis is recommended to characterize the radiograph findings further (Figure 80.2). Ideally, this should be performed with intravenous contrast in the portal venous phase, however, renal function derangement from fluid sequestration may make this impossible. The possible need for surgery is a relative contraindication to oral contrast enhancement.

Dilated sigmoid colon

Thickened odematous wall Pericolic fat stranding with hyperenhancement of

mucosal surface

Figure 80.2 Enhanced CT scan.

This single enhanced CT image acquired at a level just superior to the femoral acetabulae demonstrates dilatation and thickening of the sigmoid colon. There is hyperenhancement of the mucosa and muscularis propria, which outline an iso-attenuating oedematous submucosa. There is associated pericolic fat stranding. These findings suggest acute inflammatory change. There is no evidence of free fluid within the pelvis and no extraluminal free gas on this image, although the whole study should be reviewed to exclude perforation.

Inflammation of the colon is termed ‘colitis’ and its causes are numerous:

•Infection: bacteria (E. coli, Salmonella), parasites (amoebiasis), fungi (histoplasmosis) and viruses (HIV, CMV) can all cause pancolitis and marked wall oedema.

226

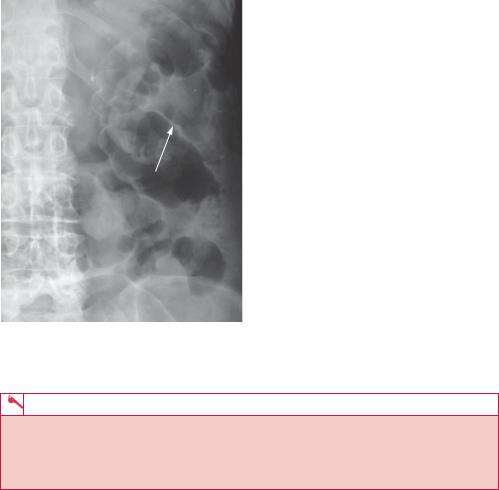

•Ischaemia: The splenic flexure/descending colon are a watershed area demarcated by the blood supply from the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. It is particularly susceptible to ischaemia of any cause (e.g. atherosclerosis), and the colitic appearances can mimic inflammatory bowel disease. The characteristic appearance of air within the wall of the colon is termed ‘pneumatosis coli’ and is highly suggestive of ischaemic colitis. It is usually a premorbid phenomenon (Figure 80.3).

Figure 80.3 Scan showing air within the wall of the colon: pneumotosis coli.

•Pseudomembranous: Often caused by an overgrowth of the Clostridium difficile bacterium related to antibiotic usage, predisposed patients can suffer a pancolitis with deterioration to toxic megacolon.

•Inflammatory bowel disease: Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease are difficult to differentiate by history alone and require histological characterization. Radiologically, UC is often left sided with shallow mucosal ulcers extending down to the rectum with small bowel sparing. Crohn’s is a discontinuous, full thickness disease, often with deep penetrating ulcers sparing the rectum and commonly seen at the terminal ileum.

•Toxic megacolon: This can occur in any form of colitis, but is particularly prevalent in UC. Uncontrolled fulminant colitis can lead to transmural involvement with rapid dilatation of the large bowel. There are large fluid shifts and the patient is often toxic and shocked. As a surgical emergency, it requires rapid identification and carries a significant risk of mortality.

Named after Leo George Rigler, an American radiologist, the eponym ‘Rigler’s sign’ was derived from his paper entitled ‘Spontaneous pneumoperitoneum: a roentgenologic sign found in the supine position’.1 Until 1941, the only documented sign of intraperitoneal free gas was seeing crescenteric gas contrasted against the diaphragm and solid abdominal viscera on erect chest radiographs. Rigler described that is it possible to ‘observe both the contour of the inner and outer wall of the bowel’1 in supine positioning when there is significant intraperitoneal free gas. This is also known as the ‘double wall sign’, and is an abnormal finding unless the patient has undergone recent surgery or laparoscopy (Figure 80.4).

227

Rigler’s double wall sign

Figure 80.4 Radiograph showing Rigler’s sign.

KEY POINTS

•The bowel is said to be dilated when the cross-sectional diameter exceeds 3cm for small bowel and 6cm for large bowel.

•Pneumatosis coli is highly suggestive of ischaemic colitis and carries high mortality.

•‘Rigler’s sign’ is pathognomonic for the diagnosis of intraperitoneal free gas.

Reference

1.Rigler, L.G. (1941) Spontaneous pneumoperitoneum: a roentgenologic sign found in the supine position. Radiology 37: 604–607.

228

CASE 81: PAIN IN THE LEFT WRIST FOLLOWING A FALL

History

A 65-year-old woman attends her local accident and emergency department following a mechanical fall. While walking her dog this morning, she slipped on the icy pavement and fell forward, putting out her left hand to break her fall. She heard a ‘crack’ and had an instant sharp stabbing pain in her left wrist. Noticing an obvious deformity and experiencing severe pain on all movements, she called her husband who collected her and bought her to hospital.

She has a history of gallstone disease and a cholecystectomy. She went through the menopause aged 55 years, and was on hormone replacement therapy for the following 6 years. She has never had a bone density scan or suffered any previous fractures. She takes no regular medication and has never taken corticosteroids.

Examination

The triage nurse has requested a wrist X-ray (Figure 81.1).

Questions

• What does this X-ray show?

• What is the common mechanism of injury and how is it treated?

Figure 81.1 Lateral radiograph of the left wrist.

229

ANSWER 81

Figure 81.1 is a lateral radiograph of the left wrist in an adult patient. There is abnormality seen in the distal radius with interruption of the normal smooth cortical line, and a linear cortical breach extending horizontally through the distal radius. There is loss of normal alignment with the distal radius fragment dorsally angulated by approximately 30 degrees. The radiocarpal joint is not involved but the carpal bones are displaced posteriorly with associated overlying soft tissue swelling. It is normal practice to look at the wrist in two views.

This anterior–posterior (AP) view of the same patient (Figure 81.2) confirms a comminuted fracture of the distal radius with dorsal angulation of the distal fragment. There is also a fracture of the ulna styloid with medial displacement of the distal fragment associated with soft tissue swelling. No other bony injury is seen, most importantly to the scaphoid. There is no radiographic evidence of scapholunate dislocation. These features are in keeping with a complex Colles’ fracture to the left wrist.

Figure 81.2 AP radiograph view of the left wrist.

This type of wrist fracture is named after Abraham Colles, an Irish surgeon from Dublin (1773–1843). A Colles’ fracture is the commonest fracture to the forearm and is usually sustained from a mechanical fall. The patient uses an outstretched hand to break the fall, with the radius fracturing horizontally approximately 2 cm from the articulating surface. The patient’s bodyweight forces the distal fracture fragment dorsally and commonly fractures the ulna styloid in the process. The nature of the injury predisposes the osteoporotic elderly and active young patients (skateboarders, snowboarders) to this type

230

of fracture. Reduction of the fracture is essential to reduce the long-term risks of fused misalignment, deformity, reduced range of movement and joint osteoarthritis. This is most commonly done in the accident and emergency department under sedation and local anaesthetic (Bier’s block). The wrist is reduced and temporarily placed in a cast, held in palmar flexion with ulna deviation to maintain the reduction. Orthopaedic assessment in the fracture clinic may leave undisplaced fractures in a cast with no further treatment, however significant deformity usually requires surgical fixation, taking into account age, hand dominance, occupation, radial variance, intra-articular extension and dorsal tilt (>20 degrees).

The four commonest adult wrist fractures to recognize are shown in Figure 81.3.

Colles fracture

Smith fracture

|

|

Figure 81.3 Adult wrist fractures. |

|

|

Reproduced from Reference 1 |

Barton fracture |

Chauffeur fracture |

with permission. |

|

In addition to Colles’ fracture, these include:

•Smith fracture: Commonly called the reverse Colles’ fracture, this is commonly seen in older osteoporotic patients who fall onto a clenched fist. A horizontal fracture to the distal radius is sustained with volar angulation of the distal fragment.

•Barton fracture: This injury, also sustained by falling on an outstretched hand, fractures the radial head vertically with dorsal angulation to the distal fragment. This has intra-articular extension and is associated with carpal dislocation.

•Chauffeur fracture: Sudden ulnar deviation and dorsiflexion causes an avulsion fracture to the radial styloid with lateral displacement of the fracture fragment. Associated with lunate dislocation, these fractures were commonly sustained by chauffeurs when an automobile backfired during a hand crank start.

KEY POINTS

•A Colles’ fracture is the commonest fracture of the forearm and is usually sustained by falling on an outstretched hand.

•Fracture reduction is essential to reduce the risk of long-term osteoarthritis.

•Fracture clinic assessment is integral in the follow-up of all fractures.

Reference

1.Dahnert, W. (2011) Radiology Review Manual, 7th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

231