Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Thomas R., Connelly J., Burke C. - 100 cases in radiology - 2012

.pdfThis page intentionally left blank

CASE 33: LOWER BACK PAIN

History

A 15-year-old girl presents to the accident and emergency department with lower back pain following a fall while taking part in gymnastics at school. She complains of a history of lower back discomfort. There is otherwise no significant medical history.

Examination

She is in pain but otherwise well. There is diffuse tenderness over the lower lumbar vertebrae but no point tenderness to suggest a fracture.

Anterior–posterior and lateral lumbar spine X-rays are obtained (Figure 33.1).

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 33.1 (a) Anterior–posterior and (b) lateral lumbar spine radiographs.

Questions

•What do the plain images show?

•Which part of the anatomy is affected?

•What other imaging would be helpful?

103

ANSWER 33

The lateral image demonstrates anterior slip of L5 on S1 by about 25 per cent of the vertebral width, otherwise termed spondylolisthesis or anterolisthesis. The degree of slip is graded in steps of 25 per cent (i.e. <25 per cent grade 1, 25–50 per cent grade 2, etc.). A lucency is seen through the pars interarticularis – the portion of the neural arch that connects the superior and inferior articular facets, suggesting a bony defect. This is otherwise known as spondylolysis. On oblique radiographs, the posterior elements form the appearance of a Scottie dog and a break in the pars interarticularis has the appearance of a collar around the neck.

A computed tomography (CT) scan has been obtained to examine the bony structures (Figure 33.2). Magnetic resonance (MR) would be useful if the nerve roots or spinal cord need to be imaged, although the bony structures are less well seen.

(a) |

(b) |

(c) |

Figure 33.2 (a) Axial, (b) sagittal and (c) oblique CT slices through the L5 vertebra showing bilateral pars defects (see arrows), widening of the spinal canal and a ‘Scottie dog’ projection with the pars defect representing the dog’s collar.

Spondylolysis is thought to be caused by stress fracturing of the pars from repeated minor trauma and may occur early in life. Hereditary pars hypoplasia is also believed to be a factor. Patients with spina bifida occulta have an increased risk for spondylolysis. Spondylolysis can also occur secondary to neoplasm, osteomalacia, osteomyelitis and bone disorders such as Paget’s disease and osteogenesis imperfecta.

The L5 vertebra is most frequently affected, a smaller proportion at L4 or L3, and it is unusual for spondylolysis to occur at several levels. Seventy-five per cent are bilateral. Lyses occur much less commonly at other lumbar or the thoracic levels.

Patients with bilateral pars defects can develop spondylolisthesis. The vertebral body slips forward while the posterior elements remain fixed so that the spinal canal widens. Stability is provided by the soft tissues and ligaments. Degenerative change is a more common cause in older patients. Increased motion of the facet joints allows movement but slip of the intact vertebra results in spinal canal stenosis and symptoms. Treatment depends on the type of slip, age of patient and symptoms and ranges from conservative management to surgical fixation.

KEY POINTS

•Spondylolysis is a defect through the pars interarticularis, usually at L5 or L4, probably the result of stress fracturing.

•Spondylolisthesis is slip, usually anteriorly, of one vertebral body on another and may be the result of spondylolysis in younger patients or, more commonly, degenerative change in older patients.

104

CASE 34: VOMITING BABY BOY

History

A 6-week-old boy is referred urgently to the paediatric department by his general practitioner (GP) with a 1-week history of vomiting after feeds and weight loss. His mother describes forceful vomiting occurring during or shortly after feeds; the vomit does not appear bile stained. He appears to have normal appetite and no other symptoms. No other members of the family seem affected.

Examination

The baby is apyrexial, mildly dehydrated with normal observations. The chest is clear and abdomen soft and not distended. There is a small palpable mass in the right upper quadrant and after feeding some peristalsis under the skin in the epigastic region is observable. You organize an ultrasound scan of the upper abdomen (Figure 34.1).

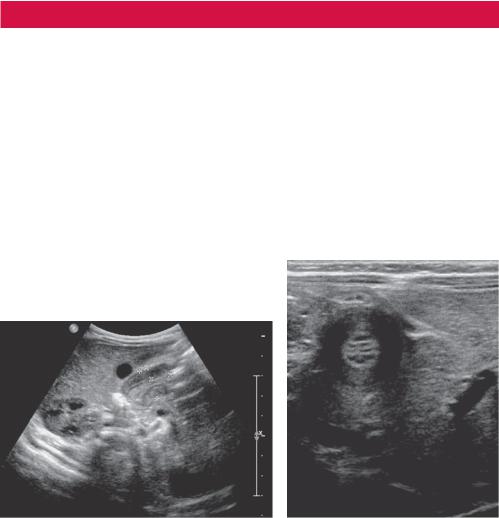

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 34.1 (a) Transverse and (b) longitudinal ultrasound images through the liver and adjacent structures.

Questions

•Which organs lie immediately behind the liver?

•What is the differential and most likely diagnosis?

•Are there any risk factors?

•What is the treatment?

105

ANSWER 34

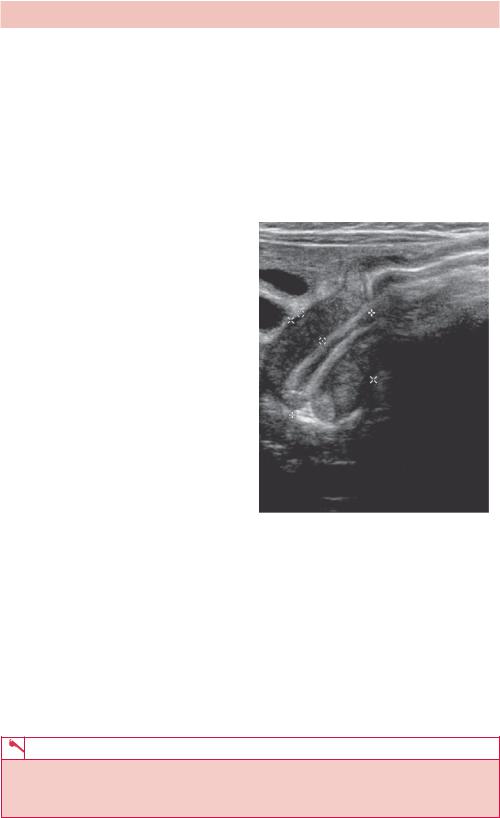

Figure 34.1a shows a transverse ultrasound view of the right upper quadrant with a prominent tubular pylorus just behind the liver in keeping with pyloric stenosis. By viewing the pylorus over a period of time (if baby allows), altered pyloric function can be viewed with limited or absent flow of stomach contents through to the duodenum and ineffective gastric peristalsis, which may sometimes be observable by eye. Pyloric muscle thicker than 4 mm, length >17 mm and transverse diameter >14 mm are criteria sometimes used, although this will depend on the age of the baby. Figure 34.2 shows transverse ultrasound with measurements.

Pyloric stenosis is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in infancy (2–4 per 1000). It is due to hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the muscular layers with thickening and lengthening of the pylorus, causing func-

tional gastric outlet obstruction. Typical features are presentation at 2–8 weeks (although can present up to 5 months). The pylorus may be palpable, about the size of a large olive. Forceful, projectile vomiting that is not bile stained is suggestive of pyloric obstruction. Blood tests typically indicate hypochloraemic alkalosis, due to vomiting gastric acid, and dehydration.

The differential diagnosis includes:

•infections including gastroenteritis and urinary tract;

•gastritis, gastroesophageal reflux, hiatus hernia;

•malrotation, pyloric atresia, web or diaphragm;

•congenital adrenal hyperplasia (due to metabolic imbalance);

•poor feeding practices.

Figure 34.2 Transverse ultrasound with measurements. The gastric mucosa is bright, the muscle dark.

If the diagnosis is not clear on ultrasound, a contrast meal and follow through that examines the stomach and small bowel is the next step. Pyloric stenosis typically shows shouldering of the gastric antrum outlet with a long, narrow pyloric canal (string sign) on a contrast meal. Malrotation and other causes of outflow obstruction also show characteristic appearances.

There is a higher incidence of pyloric stenosis in first-born boys (M: F 4:1). There is also evidence for heritability and that the condition appears to be developmental rather than congenital. The definitive treatment is surgical pyloromyotomy, where the pylorus muscle is cut longitudinally to release the pyloric tension.

KEY POINTS

•Pyloric stenosis typically presents within 2–12 weeks as non-bilious vomiting.

•Ultrasound appearances can be diagnostic with the pylorus appearing lengthened and thickened and no significant flow of stomach contents through to the duodenum.

106

CASE 35: PAINLESS HAEMATURIA

History

A 68-year-old woman is referred to the radiology department for an urgent chest radiograph after an abnormality is noted in the left kidney on ultrasound in the urology clinic. She has a recent history of painless haematuria.

Examination

There is little of note on general examination except that she looks thin. There is mild diffuse tenderness in the right loin and a possible ballotable mass on the right.

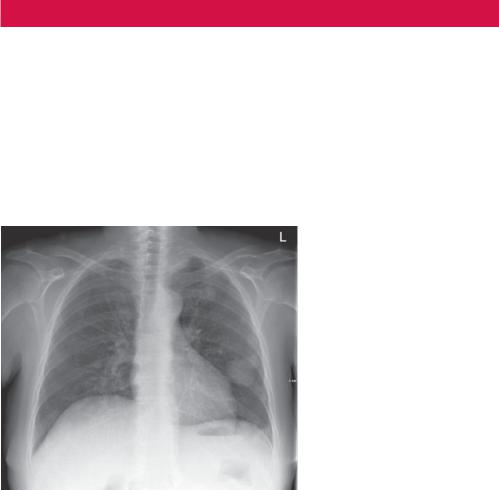

You review the chest radiograph (Figure 35.1) before the patient leaves the department.

Figure 35.1 Posterior–anterior (PA) chest radiograph.

Questions

•What does the radiograph show?

•What is the differential for this appearance?

•What imaging would you do next?

107

ANSWER 35

The chest radiograph shows several circular soft tissue lesions in both hemithoraces, most prominent on the left.

The first issue is how to describe the lesions. Convention is that a ‘nodule’ is smaller and a ‘mass’ larger than 3 cm. Nodules can be thought of as miliary (multiple, with size and appearance of seeds), small (2–5 mm) or large (>5 mm). They may be single or multiple, discrete or confluent, uniform or variable in size, contain calcification or cavities and be associated with lymphadenopathy, pleural effusions or pleural or rib lesions. Noting these features can help to narrow down the list of differentials.

In this case the list of differentials for multiple variable size soft tissue pulmonary nodules includes metastases, Wegener’s granulomatosis, rheumatoid nodules, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis (often calcified), arteriovenous malformations and abscesses. Most likely are metastases from a possible renal primary. Metastases often have a rounded mass appearance, having grown rapidly from a bloodborne deposit, whereas primary lung tumours often have an irregular, infiltrative or spiculated appearance.

The lungs are one of the most common sites for haematogenous spread of tumours, particularly from kidney, osteosarcoma, thyroid, melanoma and breast. When that list is adjusted for tumour incidence, lung metastases are most commonly seen for breast, kidney, head and neck, and colorectal tumours.

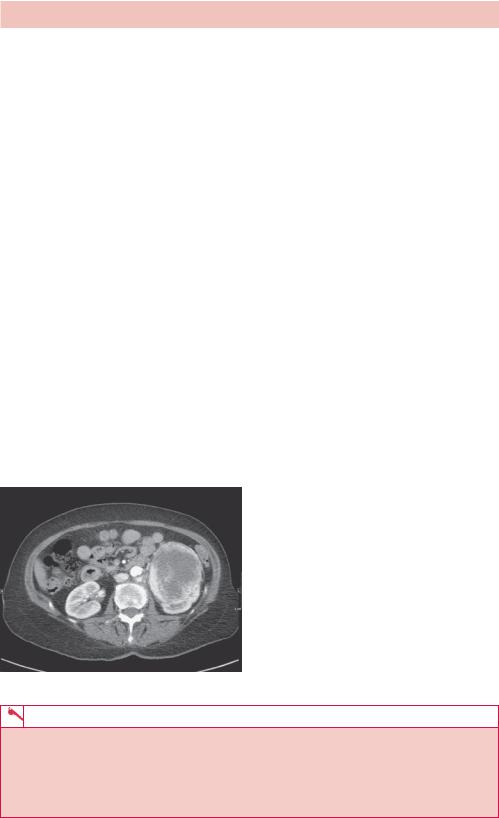

A computed tomography (CT) scan to characterize the kidney lesion and to stage the disease is required (Figure 35.2). In particular, evidence of any growth of the tumour into surrounding structures or lymph nodes or into the renal vein or opposite kidney will alter the treatment. Renal tumours account for 3 per cent of adult tumours and the large majority are renal cell carcinomas (RCCs). Thirty per cent of patients with RCC present with metastases, which in addition to lung occur in soft tissue, bone and liver.

Figure 35.2 Axial contrast-enhanced CT through the kidneys showing a large left renal tumour.

KEY POINTS

•The size, number, distribution and properties of lung nodules can help decide the differential diagnosis.

•Kidney, osteosarcoma, thyroid, melanoma and breast tumours most commonly metastasize to the lungs.

•Renal cell carcinoma is the most common adult kidney cancer.

108

CASE 36: SUDDEN ONSET WEAKNESS IN AN 80-YEAR-OLD WOMAN

History

An 80-year-old woman was brought into the accident and emergency department from her sheltered accommodation with sudden onset right-sided weakness and slurred speech. She is not known to have had a previous stroke or neurological symptoms. She has a past history of chronic obstructuve pulmonary disease (COPD) and 50 pack-years smoking.

Examination

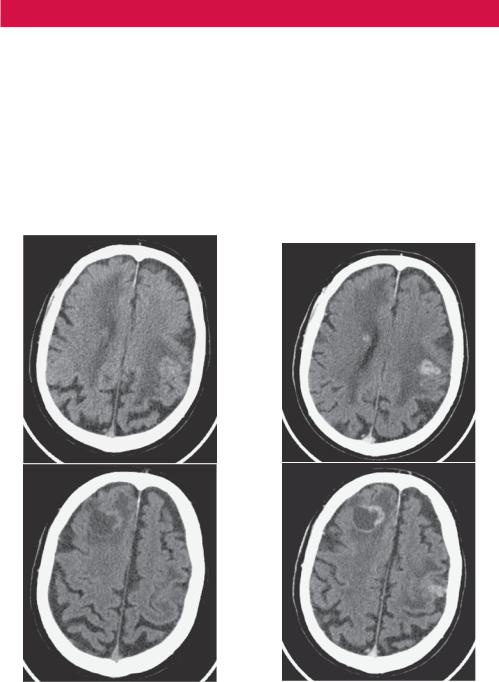

There is right-sided leg and arm weakness (3/5), mild slurring of speech and left facial droop. The chest is clear and abdomen soft and non-tender. Observations show a regular heart rate of 72/minute, blood pressure of 132/82 and no pyrexia. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head is arranged (Figure 36.1).

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 36.1 Axial CT slices through brain at two levels: (a) images without contrast; (b) images with contrast.

Questions

•What is the differential diagnosis for ‘stroke’?

•What does the CT demonstrate?

•Is contrast used regularly for head CTs?

•What is your most likely diagnosis and what other investigations would you arrange?

109

ANSWER 36

The aim of imaging is early diagnosis and to differentiate ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke. Stroke mimics include space-occupying lesions such as tumours, haematomas, arterial dissections, abscess and acute infection (often a urinary tract infection) in patients with chronic cerebral degeneration such as dementia.

The computed tomography (CT) shows low attenuation regions within the subcortical white matter of the superior right frontal lobe and posterior left frontal lobe in the region of the motor cortex. A small central high attenuation area is in keeping with haemorrhage with surrounding white matter oedema. Post contrast, both regions show avid ring enhancement.

Head CTs are almost always initially non-contrast. This is primarily to avoid obscuring acute haemorrhage or haematoma that has mildly increased attenuation compared with the surrounding brain. It also allows calcification to be identified. There are a number of locations where calcification accumulates physiologically, including the choroid plexi (posterior horns of the lateral ventricles), pineal gland and habenula (posterior end of the third ventricle), falx, basal ganglia and vascular atheroma. Physiological calcification is often symmetrically arranged or on the midline. Other calcifications may arise in lesions associated with tumours (e.g. meningiomas), infection, arteriovenous malformations or aneurysms, old haemorrhage and past surgery.

Contrast is given to improve the visibility of the vasculature (e.g. aneurysm, arterovenous malformation) or lesions that often have abnormal vessels with defective blood–brain barrier so that contrast is retained in the tissue.

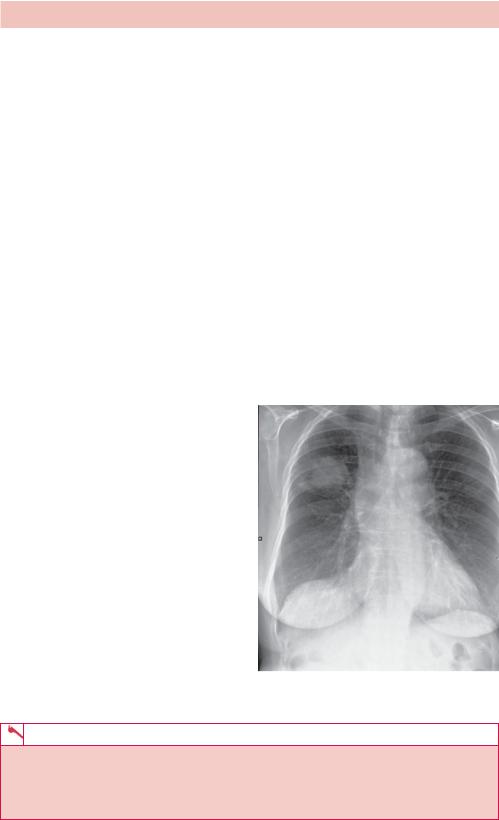

The ring-enhancing lesions in this patient’s case are most likely to be metastatic tumour deposits from a remote primary. A primary brain tumour is less likely in this age group and the clinical picture is not typical for brain abscesses, although the appearance would be quite similar. A chest radiograph would be the next investigation (Figure 36.2), given the history of smoking, although a staging CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis would be required for treatment planning.

Only a few tumours account for about 95 per cent of brain metastases, most commonly bronchial carcinoma, breast, gastrointestinal tract, renal cell carcinoma

and melanoma.

Figure 36.2 Chest radiograph showing a right mid zone mass and hilar lymphadenopathy.

KEY POINTS

•Although infarction is the most common cause of stroke symptoms, if the patient is young or the history is inconsistent, consider stroke mimics such as tumours or arterial dissections.

•Bronchial cancer is the most common metastasis to the brain.

110

CASE 37: YOUNG MAN WITH ANKLE PAIN

History

A 20-year-old man presents to the accident and emergency department with a painful right ankle after twisting during football practice. He is barely able to put his weight on the foot. The description sounds like an eversion injury. There is no other or previous injury and the patient is otherwise fit and well. There is no significant medical history.

Examination

On examination the patient appears fit and well but in pain. There is swelling and tenderness over the right lateral malleolus. There is reduced range of movement at the ankle joint. Observations are normal and there are no other significant findings.

You arrange radiographs of the ankle (Figure 37.1).

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 37.1 (a) Anterior–posterior (AP) view of the foot in 20 degrees external rotation to see the ankle mortice with minimum overlap; (b) lateral view of the ankle.

Questions

•What do the radiographs show?

•How would you describe the abnormality?

•What are the features that help with a differential diagnosis?

•What are your most likely differentials?

111