Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Thomas R., Connelly J., Burke C. - 100 cases in radiology - 2012

.pdf

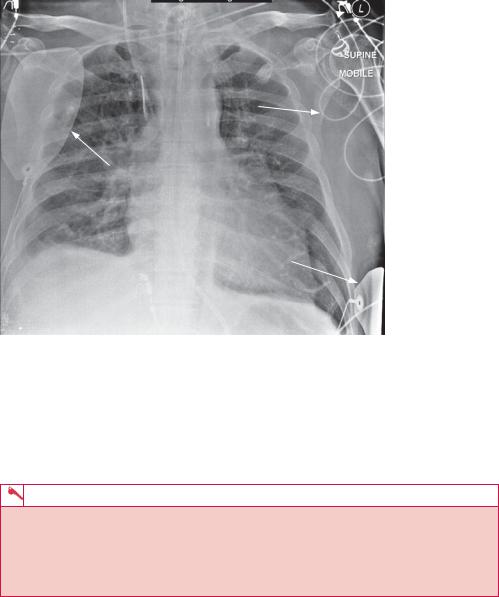

Monitoring electrods

Wires connected to electrods

Adhesive cardiac pacing pads

Adhesive cardiac pacing pads

Figure 8.4 Chest radiograph showing central line.

strategically placed metallic electrodes connected by wires to an external monitoring box. The electrodes can have a variety of appearances and the wires are draped over the patient, often lying erratically over the film. They are seen in Figure 8.4 overlying both humeral heads, and in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen.

KEY POINTS

•The presence of lines indicates an unwell patient.

•It is important not to let lines on a radiograph be a visual distraction to the underlying pathology.

•An ability to recognize all lines and the common complications associated with them is necessary.

22

CASE 9: WEAKNESS AND SLURRING WHILE OUT FOR A DRINK

History

A 67-year-old man is bought into the accident and emergency department by ambulance with new left-sided limb weakness and a left facial droop. This started 40 minutes earlier while the patient was having a pint in his local pub. Complaining of dizziness for a short while, the patient suddenly fell from his bar stool. The concerned bar tender managed to help him to an armchair and noticed that he was slurring his words and could not use his left arm to help himself up. An ambulance was called, and during this time the patient developed a left-sided facial droop. He remained alert throughout but appeared anxious and disorientated.

The patient is known to the hospital, and has attended previously with attacks of angina. There is no history of myocardial infarction, but he is on tablets for hypertension and dyslipidaemia. He is a smoker and lives at home with his wife. There have been no recent intercurrent illnesses.

Examination

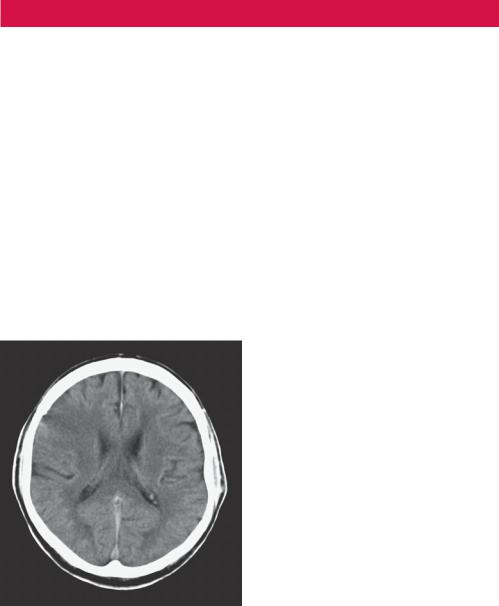

A computed tomography (CT) scan was performed as part of his medical assessment (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 CT scan.

Questions

•What does the CT scan show?

•What is a stroke?

•What are the treatment options?

23

ANSWER 9

This (Figure 9.1) is a single image from an unenhanced CT scan acquired at the level of the corona radiata. There is a background of generalized involutional change in keeping with the patient’s age, and some hemispheric white matter low attenuation suggestive of small vessel disease. Within the right fontal lobe there is a wedge-shaped area of low attenuation with loss of the normal grey/white matter differentiation and extension to the cortical surface. There is mass effect with the adjacent sulci effaced, but no evidence of midline shift or hydrocephalus. There is no evidence of haemorrhage or mass lesion. The image findings are consistent with an acute right middle cerebral artery (MCA) infarction on a background of generalized ischaemic change.

Any vascular interruption within the brain starves distal tissues of blood causing cell death and neurological deficit. This is termed a ‘stroke’ and is usually thromboembolic (90 per cent) in aetiology,1 and less commonly haemorrhagic. In the acute setting, unenhanced cranial CT is used to differentiate between the two. Treatment pathways for infarction require antiplatelet therapy, but haemorrhage needs to be excluded to avoid the catastrophic effects of anticoagulation.

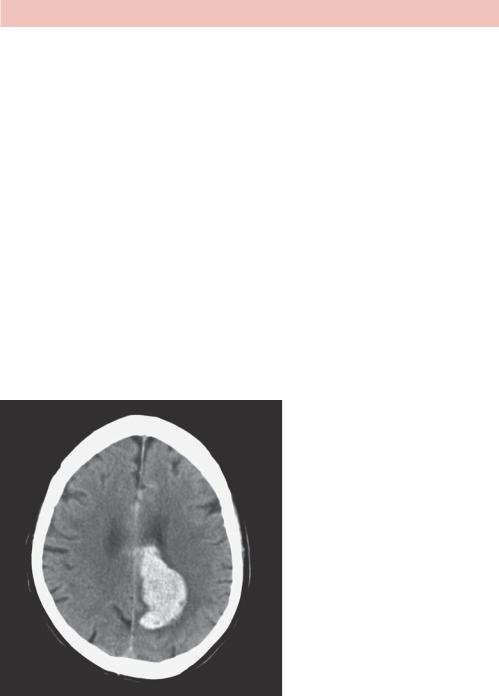

Figure 9.2 demonstrates an acute intracerebral haemorrhage within the left cerebral hemisphere. Cranial CT has a high sensitivity (89 per cent) for haemorrhagic stroke. Acute blood within the brain parenchyma appears white on CT (attenuation Hounsfield unit (HU) of 60–70) and stands out against the adjacent darker brain tissue. Treatment for haemorrhagic stroke is usually conservative and supportive.

Figure 9.2 CT scan showing acute intracerebral haemorrhage.

In acute infarctive stroke, cranial CT is relatively insensitive (45 per cent at ictus rising to 74 per cent by day 11)1 and radiological features can vary. A normal cranial CT does not exclude thromboembolic stroke, and should neurological deficit fully resolve within 24 hours, this is termed a transient ischaemic attack (TIA). The significance of patients presenting with a TIA should not be underestimated, and these patients should be considered as an acute medical emergency requiring risk stratification to prevent further non-

24

fatal disabling stroke. In the setting of an acute infarctive stroke or TIA, the cranial CT may be normal. Large thromboembolic strokes classically demonstrate a wedge-shaped area of low density with blurring of the grey/white matter junction. In the image from the CT scan taken from our patient (Figure 9.1), there is loss of grey/white matter differentiation within the right fronto-parietal region compared to the contralateral side. This area is shaded grey in Figure 9.3, which shows the subtle features of an acute thomboembolic stroke.

Figure 9.3 CT scan.

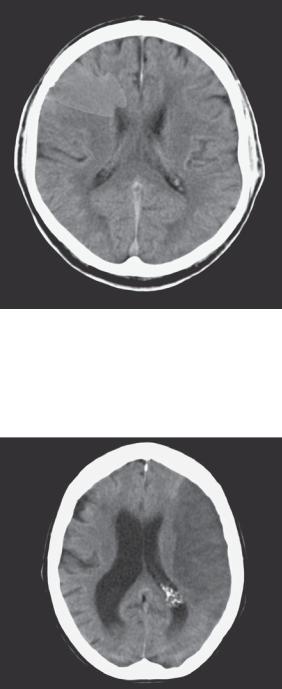

In larger infarctive strokes, associated vasogenic oedema can press upon adjacent brain tissue and cause mass effect. The CT findings can usually localize the cerebral artery involved, most commonly the middle cerebral artery (MCA). Figure 9.4 shows an unenhanced axial CT slice demonstrating a well-demarcated area of low attenuation, with loss of the grey/white matter interface and mass effect, in keeping with a large acute left MCA infarct.

Figure 9.4 Unenhanced axial CT slice.

25

Many hospitals are now offering thrombolysis therapy for acute thromboembolic stroke. Any history of intracranial haemorrhage is an absolute contraindication, and performing and interpreting a cranial CT is therefore essential prior to treatment. Some other contraindications are listed in Table 9.1 in the criteria taken from the National Institute of Health and Clinical Evidence (NICE) guidance.2 Thrombolysis therapy has to be administered within 3 hours of symptom onset and speed of brain imaging is very important. Without revascularization, neuronal demyelination causes atrophy of brain tissue with time, and the patient is left with a permanent neurological deficit. In the case of our 67-year-old patient, he may qualify for stroke thrombolysis and a senior stroke physician should initiate this quickly all criteria having been met.

Table 9.1 Criteria taken from the National Institute of Health and Clinical Evidence (NICE) guidance2

Inclusion criteria |

• Clinical signs and symptoms of a definite acute stroke |

|

• Clear time of onset |

|

• Presentation with 3 hours of onset |

|

• Haemorrhage excluded by CT scan |

|

• Aged between 18 and 80 years |

Contraindications |

• Any significant bleeding disorder within the last 6 months |

|

• Any significant head injury within the last 3 months |

|

• Current warfarin treatment and an international normalized ratio (INR) |

|

>1.4 |

|

• Suspected subarachnoid haemorrhage with a normal CT |

|

• Acute pancreatitis |

|

• Bacterial pericarditis or endocarditis |

|

• Active hepatitis or portal hypertension |

|

• Documented bleed from abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) in last |

|

3 months |

|

|

KEY POINTS

•Acute thromboembolic stokes classically demonstrate a wedge-shaped area of low attenuation with blurring of the grey/white matter junction.

•Transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) should be treated as a medical emergency as a sign of impending stroke.

•Many hospitals now provide systemic thrombolysis for the treatment of acute thromboembolic stroke.

References

1.Dahnert, W. (2007) Radiology Review Manual, 6th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

2.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2007) Alteplase for the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. www.guidance.nice.org.uk/TA122.

26

CASE 10: BACK PAIN RELIEVED ONLY BY ASPIRIN

History

A 23-year-old caucasian man presented to the accident and emergency department (A&E) with back pain. Usually fit and healthy, he has suffered from achy throbbing back pain for the last 6 months. Always in the same position in his lower back, it is there intermittently but has increased in frequency over the last 2 weeks. The pain is worse at night and it often wakes him from sleep. He denies any trauma, weight loss or symptoms related to his bladder or bowel movements.

His general practitioner diagnosed occupation-related back pain in relation to the patient’s job as a farmer, and recommended rest while prescribing several combinations of analgesia with little symptomatic relief. He does describe marked improvement in his symptoms with aspirin, but the pain often returns after only an hour. Waking up tonight, he was frustrated with the pain at home and attended A&E.

Examination

On examination he looks healthy but in mild discomfort. He has full range of movement with no evidence of bony tenderness on palpation. Cardiovascular, respiratory and abdominal systems are normal. X-ray is shown in Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1 Plain radiograph.

Questions

•What does the plain radiograph demonstrate?

•What is your differential for these findings?

•What further investigations need to be performed?

27

ANSWER 10

Figure 10.1 is a plain anterior–posterior (AP) radiograph of the lower thoracic and lumbar spine in an adult male patient. The vertebral bodies demonstrate normal alignment in the AP view with normal vertebral body height preserved throughout. There is an abnormality centred on the right L4 pedicle with expansion of the cortex and dense sclerosis. The adjacent transverse process also appears expanded compared to the contralateral side but there is no evidence of periosteal reaction. The psoas muscle shadow is preserved, making psoas abscess unlikely and there is no evidence of a large soft tissue component. There is no evidence of fracture but a mild scoliosis is demonstrated at this level concave to the right.

The differential for these appearances in a young caucasian man includes:

•osteoid osteoma;

•osteoblastoma;

•healing fracture;

•sclerosing osteomyelitis (e.g. tuberculosis, syphilis);

•Brodie’s abscess;

•osteoblastic metastasis;

•lymphoma;

•primary bone tumour (e.g. osteosarcoma).

Further radiological imaging is recommended and a choice needs to be made as to which modality will provide the best diagnostic yield with minimal inconvenience and radiation dose to this young patient. Considering the likely osseous location of the lesion, a computed tomography (CT) scan would have superior resolution compared to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Bone scintigraphy would also be beneficial but not as the firstline imaging modality following a plain film radiograph.

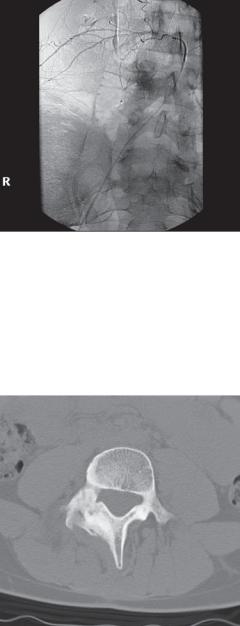

Figure 10.2 is a single axial slice of an unenhanced CT scan acquired at the level of the L4 vertebral body viewed with bone windows. Within the right pedicle there is a welldefined 17 mm lesion (arrow) that has a narrow zone of transition and is predominantly lytic in nature with some central calcification. There is diffuse sclerosis and expansion of the adjacent lamina and transverse process, with no evidence of periosteal reaction, spinal canal encroachment or pathological fracture. No soft tissue component is demonstrated. These features are in keeping with an osteoid osteoma, however considering its size (>15 mm) it is more appropriately described as an osteoblastoma.

Osteoid osteoma

Figure 10.2 Unenhanced CT scan.

28

Osteoblastomas are rare benign tumours of the bone composed of multinucleated osteoclasts with irregular trabeculated bone and osteoid, surrounded by highly vascular fibrous connective tissue.1 The commonest sites of involvement are around the knee joint in the long bones and within the posterior elements of the spine. They have unlimited potential for growth and carry a risk of malignant degeneration, therefore requiring definitive curative treatment at diagnosis.

The main treatment options include surgical removal, endovascular embolization, percutaneous CT-guided removal or percutaneous radiofrequency ablation. In this case, endovascular treatment was attempted (Figure 10.3).

Figure 10.3 Angiographic image at embolization.

This angiographic image obtained at embolization (Figure 10.3) demonstrates a blush of contrast overlying the pedicle of the L4 vertebrae on selective cannulation of the right L4 lumbar artery. The arterial supply to this osteoblastoma was embolized with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and two microcoils. Follow-up 2 months later revealed an asymptomatic patient, and successful treatment was confirmed on CT with complete sclerosis at the site of the previous osteoblastoma (Figure 10.4).

Figure 10.4 CT scan post embolization.

29

KEY POINTS

•When deciding on an imaging modality, consider which investigation will offer the best diagnostic yield with minimal patient inconvenience and radiation dose.

•Osteoblastomas are rare benign vascular tumours of the bone.

•Subclassified according to size, an osteoid osteoma larger than 15 mm is termed osteoblastoma.

Reference

1.Dahnert, W. (2007) Radiology Review Manual, 6th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

30

CASE 11: A PERSISTENT COUGH IN AN EX-SMOKER

History

You are asked to review a 67-year-old man in the chest clinic. He has been sent by his general practitioner (GP) who has been treating him for a cough. His symptoms started 3 weeks ago, at about the same time that the patient decided to stop smoking. The cough is chesty but non-productive, and is there constantly, but not worse, at night. He has no other new symptoms and is no more short of breath than usual, with an exercise tolerance of approximately 200 m. His appetite is unchanged and he has not lost weight. He does report occasional streaks of fresh red blood in the sputum on deep coughing.

The patient has a past medical history of excessive alcohol intake and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). He had two previous admissions to hospital with decompensated liver disease, but has now abstained from alcohol for over a year. His last ultrasound scan confirms a degree of liver cirrhosis. He has smoked with a 60 pack-year history. He has never been admitted to intensive care with exacerbations of COPD, but has been treated for pneumonia in the past. He recently decided to stop smoking as his new girlfriend does not like to ‘kiss an ashtray’.

Examination

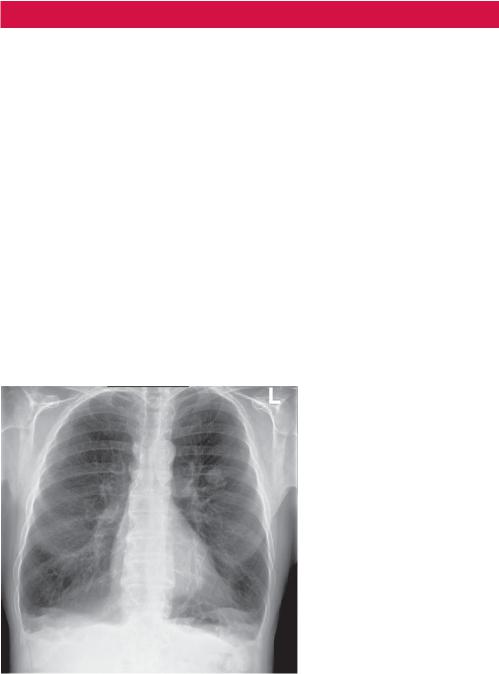

As part of his management, the GP performed a chest radiograph (Figure 11.1) and then referred him to the chest clinic.

Figure 11.1 Chest radiograph.

Questions

•What does this chest radiograph demonstrate?

•What further radiological investigations are required?

•What is PET scanning?

31