Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Thomas R., Connelly J., Burke C. - 100 cases in radiology - 2012

.pdf

While in the radiology department, the child becomes unresponsive and is intubated to maintain his airway.

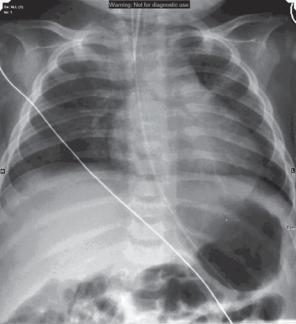

Figure 68.2 Chest radiograph post intubation and nasogastric (NG) tube insertion, windowed to optimize the bone appearance.

Questions

•What head injury does the child have?

•What else would you check for on the CT scan?

•Are further scans of the head indicated?

•Is there any sign of injury on the chest radiograph?

•What differential diagnoses should you consider?

182

This page intentionally left blank

ANSWER 68

The skull imaging shows a complex fracture of the left parietal bone extending from the vertex inferiorly with some displacement of the fractured fragments. Not shown but also apparent on the CT is a small subdural haemorrhage below the fracture. No signs of raised intracranial pressure such as bulging fontanelles and compressed cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) spaces are seen and the brain parenchyma and ventricles appear normal. The patient and images are reviewed by the neurosurgical centre.

On the chest radiograph, three posterior left rib fractures are seen overlying the heart shadow with associated callus formation. The chest otherwise appears normal.

The unsaid differential so far is non-accidental injury (NAI), however, it is important to consider the alternatives, if only to dismiss them, as the diagnosis of NAI has significant consequences. Other differentials include accidental trauma (but current injuries are not in proportion to the history), birth trauma (too long ago), osteogenesis imperfecta (no family history, no osteopenia seen) and rickets (requires imaging of long bone metaphyses).

Features that make NAI more likely are multiple fractures of varying ages, fractures inconsistent with age or history or in unusual positions, posterior (rather than lateral) rib fractures, metaphyseal corner fractures in children that have not started crawling/walking and skull fractures that are complex, multiple, cross-sutures or not in the parietal bone.

Once a diagnosis of NAI has been considered as possible, the child is admitted for treatment and retained on the ward. The findings and management are reviewed by the most senior paediatrician and social care services are immediately involved. In terms of further imaging, a skeletal survey is done to systematically document all and possible age of bony injuries. If the CT is abnormal or there are neurological symptoms or ongoing concern, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is done that may show subdural haematomas of varying ages or cortical contusions or shearing injuries from shaking injury. Delayed imaging may be helpful to show injuries acute at the time of presentation and not easily seen (Figure 68.3).

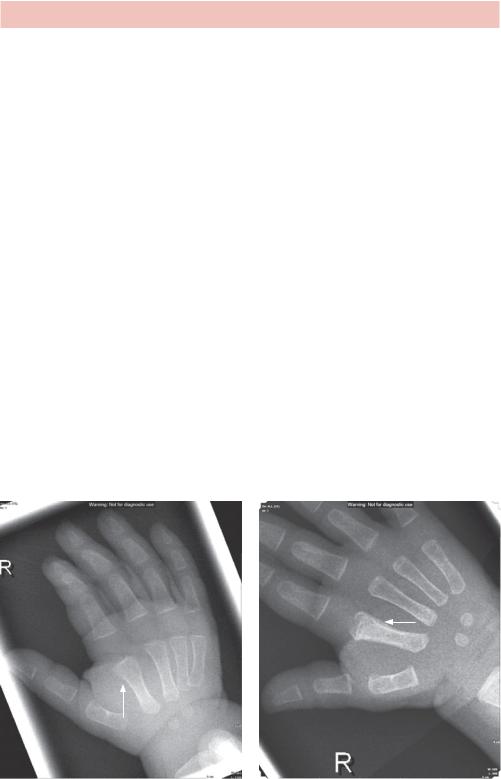

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 68.3 (a) Acute and (b) delayed images of the right hand showing a fracture of the second finger metacarpal (see arrows) with a step in image a) and sclerosis and periosteal reaction in b).

184

KEY POINTS

•NAI is a differential diagnosis of any childhood fracture, although inconsistent history, unusual and multiple fractures make the diagnosis more likely.

•Get senior and specialist review if you are suspicious.

185

This page intentionally left blank

CASE 69: ABDOMINAL DISTENSION IN A WOMAN WITH

OVARIAN CANCER

History

A 65-year-old woman presents to the accident and emergency department with vomiting. She is known to have metastatic ovarian carcinoma with a large primary tumour that is invading surrounding structures. There are lung and liver metastases. She has recently completed a course of chemotherapy. She complains of a long history of variable bowel habit and has not opened her bowels for the last 2 days.

Examination

She looks thin and in discomfort. There is mild dehydration, no fever and observations are normal. She has a distended abdomen that is soft but generally tender. There are hyperactive bowel sounds on auscultation. Her chest is clear and heart sounds are normal.

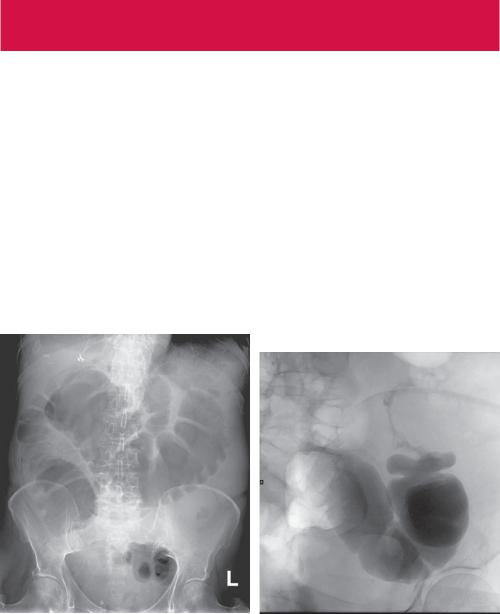

You arrange an abdominal radiograph (Figure 69.1), review the staging computed tomography (CT) scan of the pelvis from a few months previously that describes metastatic masses and organize a water-soluble contrast enema (Figure 69.2).

Figure 69.1 Abdominal radiograph. |

Figure 69.2 Water-soluble contrast enema. |

|

Oblique projection of the sigmoid colon. |

Questions

•What does the abdominal radiograph show?

•What does the enema show?

•Where does the problem lie?

187

ANSWER 69

The large bowel is investigated by introducing gas or contrast rectally, known as an enema. Barium enemas and CT colonograms require thorough bowel preparation and a bowel relaxant such as buscopan is given. In a barium enema, barium contrast is introduced into the bowel through a rectal tube and then mostly removed after coating the large bowel round to the caecum. Gas is then introduced to distend the bowel and radiographs are taken in several planes to view the entire bowel wall. In a CT colonogram, gas only is introduced to distend the bowel. Supine and prone scans are made with intravenous contrast.

A water-soluble contrast enema is typically used in acute situations where there is risk of perforation or likelihood of surgery, and does not require bowel preparation. Leakage of barium into the abdominal cavity runs a high risk of barium peritonitis, although in relatively healthy patients the risk is less than 1 in 3000.

The abdominal radiograph (Figure 69.1) shows gas within dilated bowel that demonstrates a haustral pattern (fold involving only part of the bowel wall) characteristic of large bowel. The position is typical of the caecum and transverse colon with only a small amount of gas in the descending and sigmoid colon. No gas is seen in the small bowel, suggesting the terminal ileal valve is patent. The dilated bowel pattern suggests there is an obstruction at the splenic flexure level.

In the water-soluble contrast enema (Figure 69.2), contrast was seen to flow through the rectum, and into the sigmoid colon. Contrast passed no further than the mid-sigmoid colon where a stricture was seen. The imaging suggests two strictures postioned in the descending and mid-sigmoid colon.

The history and staging CT indicate that there is metastatic ovarian disease. Ovarian carcinoma is the second most common gynaecological malignancy and fifth leading cause of cancer deaths in women. Risk factors include nulliparity, early menarche, late menopause and positive family history of ovarian, breast and early colorectal cancer. It is often discovered late as abdominal symptoms of pain and distension, bowel habit change, urinary frequency are often intermittent, non-specific and dismissed as common abdominal twinges. The tumour spreads by direct extension, intraperitoneal implantation (often with ascites to produce omental deposits or ‘omental cake’) and lymphatic and haematogenous spread, commonly to liver and lung. In this patient, there is bowel obstruction remote from the tumour that invades the sigmoid colon and this may reflect intraperitoneal implantation.

There are two aspects to this patient’s treatment. One is to relieve the immediate problem of obstruction and the other is treating the underlying disease. With widespread metastases the underlying disease is treated with chemoand radiotherapy. The obstruction is treated by palliative surgery to create a colostomy or stent insertion.

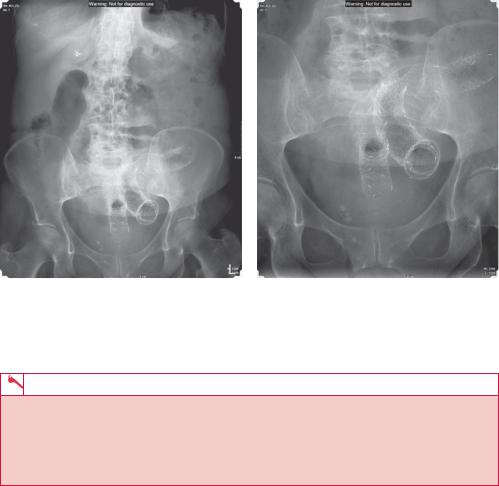

Increasingly stents are being used for palliative treatment of strictures using either fluoroscopy (movable X-ray camera) or endoscopy to pass a wire through the stricture and then fluoroscopy to insert the stent.

188

(a) (b)

Figure 69.3 Abdominal radiograph showing stents in the rectosigmoid and descending colon.

KEY POINTS

•Bowel obstruction can be diagnosed if there is a transition point, where the bowel size changes due to an intrinsic or extrinsic cause.

•Water-soluble contrast enemas are used in acute situations where the risk of perforation or imminent surgery is high.

•Stents can be used to treat strictures, particularly in palliative care.

189

CASE 70: WOMAN WITH A BREAST LUMP

History

A 48-year-old woman attends her general practitioner (GP) having noticed a lump in her left breast while showering. The lump was non-tender and there had been no associated discharge. She took no medication. She had never taken the oral contraceptive pill and although recently post-menopausal, she had never taken hormone replacement therapy. There was no family history of breast cancer. She was otherwise fit and well with no previous medical or surgical history.

Examination

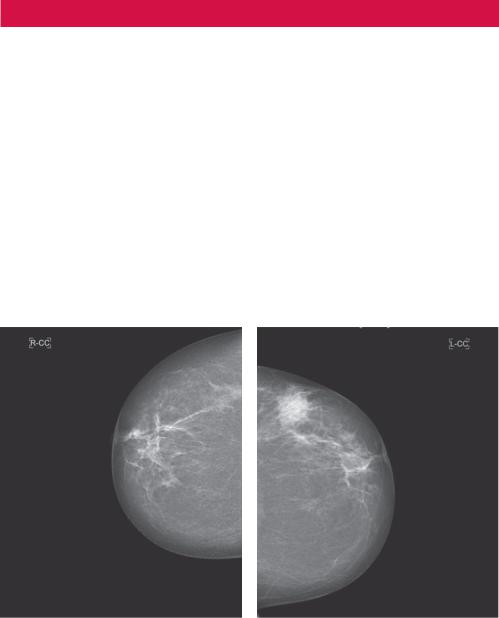

On examination there is a firm mass laterally and superiorly (in the upper outer quadrant). There are no overlying skin changes, but the mass felt firm and moves when tensing the pectoral muscles and asking the patient to raise her hands above her head. There is also evidence of palpable left axillary lymph nodes. She is referred to the local breast service symptomatic clinic. On arrival she has a standard set of mammograms taken (Figures 70.1 and 70.2).

Figure 70.1 Standard cranial–caudal mammograms.

190

Figure 70.2 Standard medio-lateral-oblique mammograms.

Questions

•What do you notice on the mammograms?

•Which age group of women attend breast screening?

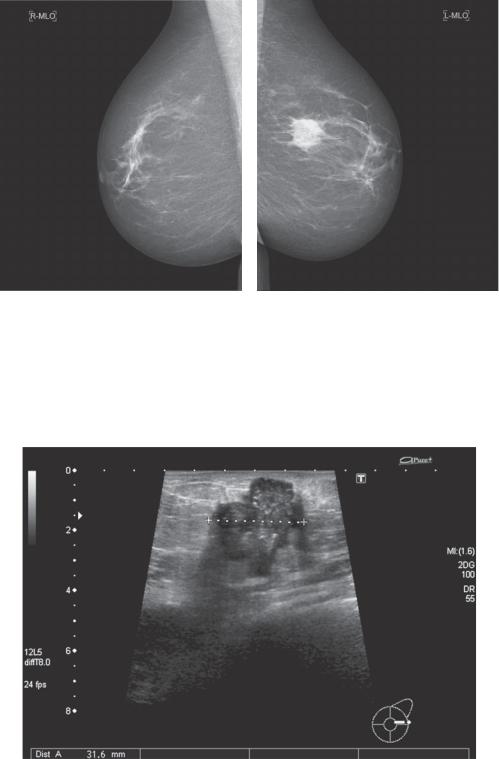

•What does the ultrasound in Figure 70.3 demonstrate?

Figure 70.3 Ultrasound.

191