Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Thomas R., Connelly J., Burke C. - 100 cases in radiology - 2012

.pdf

ANSWER 73

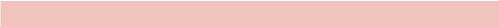

The plain radiograph (Figure 73.1) shows loss of disc and vertebral height at L4 and L5.

In many ways the MR images (Figure 73.2) complement the plain radiograph. Although the bone cortex appears dark, the marrow is bright due to fat. Loss of normal fat signal in L4 and 5 vertebral bodies results from inflammation and increased water signal. Contrast enhancement also reflects the pathological processes centred on the disc and affecting the bone. MR is also excellent for looking at soft tissues, particularly in this case the anterior paravertebral soft tissue mass as well as soft tissue impinging into the spinal canal and on to the nerve roots and the spinal cord itself.

With this patient’s history there is a risk of immune suppression and a high risk of infection and the most likely diagnosis is infective discitis. Despite his denial, the injection marks without any other explanation makes it likely that he uses intravenous drugs. The differential diagnosis of malignancy is quite unlikely as this tends to affect primarily the vertebra. Osteomyelitis is also a differential if there is not disc involvement, however, in this case it is coexistent with the discitis.

Infection in the spine is typically the result of either bloodborne spread or through an invasive procedure. Infections can be either pyogenic or non-pyogenic. Pyogenic discitis most commonly involves Staphylococcus aureus or gram-negative bacilli in intravenous drug users or immunocompromised patients. Non-pyogenic discitis may be caused by tuberculosis (TB).

In children, where there is still vascularization of the disc, the infection arises in the disc. In adults, the infection arises in the vertebral endplate and then crosses the disc to the next endplate. Typical changes seen on imaging include loss of disc height and increasing loss of vertebral endplates with destruction and collapse. There may be formation of adjacent soft tissue masses or collections that may, particularly in TB, spread beneath the longitudinal ligaments to involve multiple levels.

Diagnosis typically requires identification of the organism. In some cases this may be secondary to infection or a collection elsewhere and identified on blood or other sample culture. Otherwise a biopsy is required to obtain some infected tissue. This is typically done using image-guided needle biopsy to negotiate the nerve roots and position the needle tip in the optimum position (Figure 73.3). This patient’s biopsy yielded TB.

202

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 73.3 Fluoroscopic (movable X-ray camera)-guided biopsy of the affected disc showing the needle position.

KEY POINTS

•Lower back imaging is indicated in people with ‘red flag’ symptoms or signs suggesting spinal malignancy, infection, fracture, cauda equina syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis or another inflammatory disorder.

•Discitis often occurs with spinal osteomyelitis.

•MR allows the soft tissue extent of the infection to be assessed.

203

This page intentionally left blank

CASE 74: A CHILD WITH AN INJURY

History

An 11-year-old boy is playing at an adventure park when he falls on the climbing frame, catching his left thumb as he lands. There is immediate pain and swelling and he is unable to move his thumb. His mother takes him to the local accident and emergency department for evaluation.

Examination

He is distressed. His thumb is swollen with bony tenderness maximal in the region of the thumb proximal pharynx and metacarpal. There is virtually no range of movement at the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint or the interphalangeal joint. Capillary refill is normal (less than 2 seconds) and sensation is intact distally. A request is filled out for trauma views of the thumb to exclude a suspected fracture. The radiographs are seen in Figure 74.1.

(a) |

(b) |

Figure 74.1

Question

• What do the trauma views of the thumb demonstrate?

205

ANSWER 74

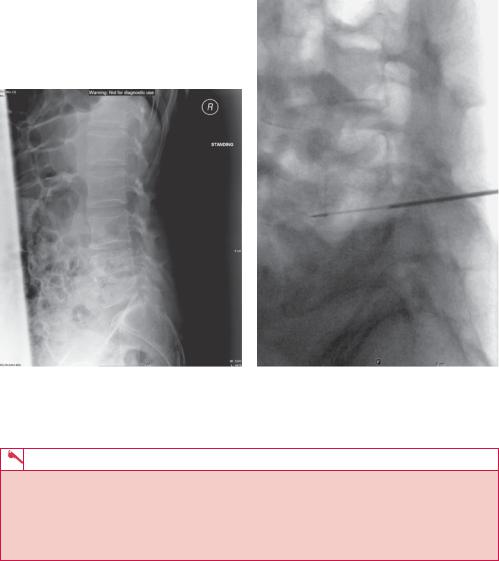

On the first radiograph (Figure 74.1a) it is difficult to appreciate a bony injury, but the second trauma view (Figure 74.1b) clearly demonstrates a fracture line passing through the base of the thumb proximal phalynx metaphysis into the epiphyseal plate. The fracture line does not, however, pass through into the epiphysis. This is the classical appearance of a Salter–Harris type II fracture.

Salter–Harris fractures are fractures through a growth plate and, as a result, unique to paediatric patients. They are common injuries found in children, occurring in approximately 15 per cent of long bone fractures. These fractures are classified according to the involvement of the physis, metaphysis and epiphysis. This categorization of the injuries is important because it not only affects patient treatment but may also alert the clinician to potential longer term complications.

There are nine types of Salter–Harris fracture in total, although types I–V are the most commonly referred to and were those described originally (the rarer types VI–IX have been added subsequently). The radiographic findings vary according to the type of Salter– Harris fracture.

The most common type of Salter–Harris fracture, is the type II fracture (see arrow Figure 74.2). This occurs through the physis and metaphysis, and the epiphysis is not involved in the injury (no fracture is observed in the epiphysis).

Figure 74.2

Salter–Harris type II fractures tend to occur after age 10. The mechanism involves shearing or avulsion with angular force. There is cartilage failure on the tension side. Metapetaphyseal failure occurs on the compression side. There is a division between epiphysis and metaphysis except for a flake of metaphyseal bone, which is carried with the epiphysis. The metaphyseal fragment is sometimes called the Thurston–Holland frag-

206

ment. These fractures may cause minimal shortening, however healing is usually rapid and Salter–Harris type II injuries rarely result in functional limitations.

With type I Salter–Harris fractures, initial radiographs may suggest separation of the physis although this separation may not be apparent and soft tissue swelling typically overlying the physis may provide the only clue. Follow-up radiographs within 2 weeks after injury help establish the diagnosis. Adjacent sclerosis and/or periosteal reaction along the epiphyseal plate supports the diagnosis of a Salter–Harris type I fracture. The growing physis is not usually injured in type I fractures, however, and growth disturbance is uncommon.

The type III fracture passes through the physis and extends to split the epiphysis. The fracture crosses the physis and extends into the articular surface of the bone. Type IV injuries pass through the epiphysis, physis and metaphysis. As with type III fractures, the type IV pattern is an intra-articular injury and therefore can result in chronic disability. Type V fractures are compression/crush injuries of the epiphyseal plate, without associated epiphyseal or metaphyseal fracture. The initial plain radiographs in type V fracture may not show a fracture line (similar to type I fractures). Soft-tissue swelling at the physis, however, is usually present. The clinical history is central to the diagnosis of type V fractures and a typical history is that of an axial load injury. Type V injuries have a poor functional prognosis.

KEY POINTS

•Salter–Harris fractures are fractures through a growth plate.

•Imaging findings vary according to the type of Salter–Harris fracture.

•The most common type of Salter-Harris fracture is the type II fracture which occurs through the physis and metaphysis (the epiphysis is not involved in the injury).

•The diagnosis of type V may be particularly difficult, however is important as these injuries have a poor functional prognosis.

•Two views are required in the evaluation of all cases of traumatic injury.

207

This page intentionally left blank

CASE 75: A RENAL TRACT ABNORMALITY

History

A 60-year-old man presents to his general practitioner (GP). Over the course of the last month he has noted bright red blood in his urine. He had hoped that it would simply go away but instead he has now developed loin discomfort, particularly on the right. He has not felt feverish or lost any weight. He is an ex-smoker and takes antihypertensive medication, but otherwise he has been well.

Examination

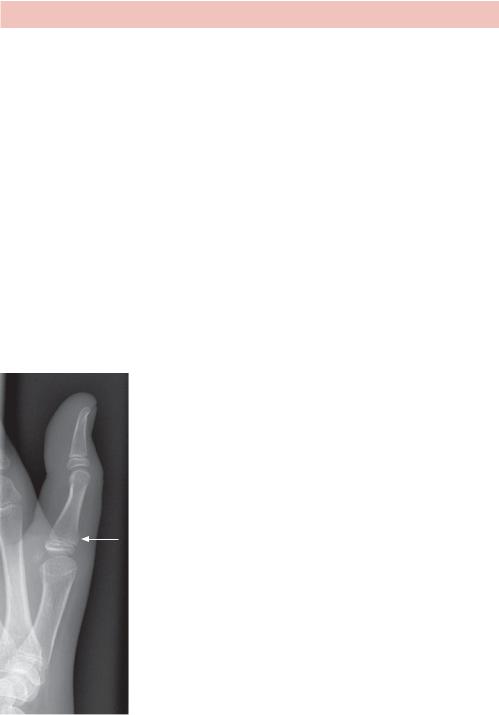

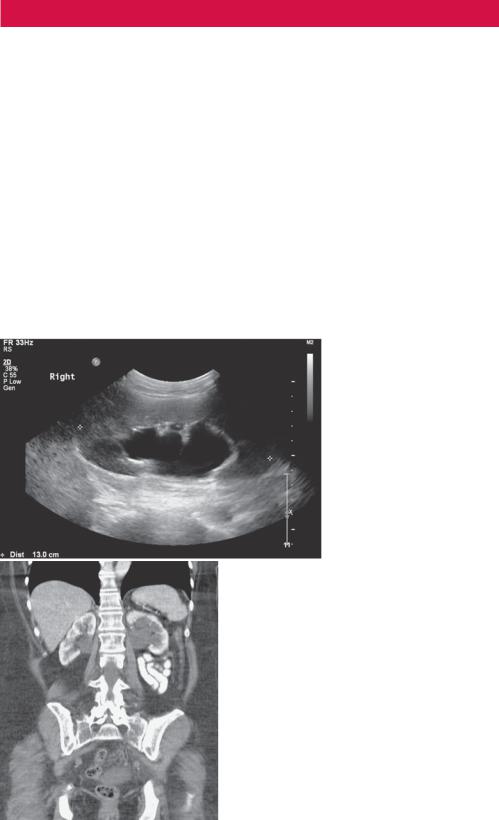

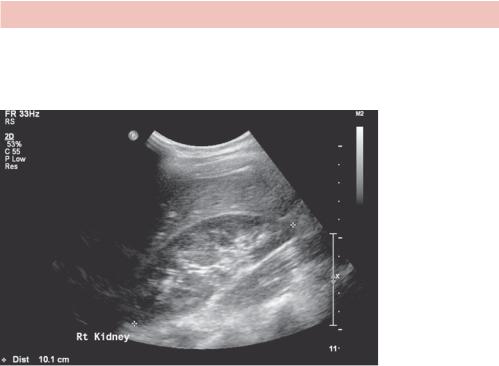

He was afebrile and his observations were all within normal limits. Upon palpation the abdomen was soft and no mass was felt. There was tenderness in the right renal angle but no direct pain on palpation. His white cell count was slightly elevated at 13 × 109/L and his C-reactive protein (CRP) is 20 mg/L. He also demonstrates a mild normocytic anaemia with a haemoglobin of 10.4 g/dL. Urine dipstick reveals frank blood. He is referred for an ultrasound scan which is reported as ‘bilateral hydronephrosis, although the bladder was suboptimally distended therefore could not be completely evaluated.’ One longitudinal image of the right kidney is seen in Figure 75.1. On the basis of the ultrasound scan, further imaging with computed tomography (CT) was arranged with the local radiology department. A coronal reconstructed image is seen in Figure 75.2.

Figure 75.1 Ultrasound image.

Question

• What do the ultrasound image in Figure 75.1 and the CT image in Figure 75.2 demonstrate?

Figure 75.2 CT scan.

209

ANSWER 75

Figure 75.1 demonstrates dilatation of the right renal pelvicalyceal system consistent with hydronephrosis. Compare this appearance with that of a normal unobstructed kidney in Figure 75.3.

Figure 75.3 Ultrasound of normal kidney.

Figure 75.2 shows a coronal contrast-enhanced CT image demonstrating dilatation of the renal collecting system bilaterally.

This patient has bilateral hydronephrosis (seen on ultrasound and CT) in combination with frank haematuria. A cystoscopy was then arranged which confirmed the presence of a bladder lesion obstructing both ureteric orifices.

Hydronephrosis is distension and dilatation of the renal pelvis calyces, usually caused by the obstruction of the free flow of urine from the kidney(s), and may lead to progressive atrophy of the kidney(s). This case demonstrates only one cause of hydronephrosis.

A multitude of causes exist for hydronephrosis and hydroureter, ranging from benign processes, such as the physiologic hydroureteronephrosis of pregnancy, to potential lifethreatening situations, such as infected hydronephrosis or pyonephrosis. Classification can be made according to the level within the urinary tract (interruption can occur anywhere along the urinary tract from the kidneys to the urethral meatus) and whether the aetiology is intrinsic, extrinsic or functional. Causes at ureteric level can be intrinsic (for example, ureteropelvic junction stricture, blood clot, retrocaval ureter), functional (for example, gram-negative infection or neurogenic bladder) or extrinsic (for example, retroperitoneal or pelvic malignancy or pregnancy). At the level of the bladder intrinsic causes include carcinoma (as in this case), calculi, cystocele or diverticula; functional causes include vesico-ureteric reflux; and extrinsic causes again include malignancy and pelvic lipomatosis. Urethral causes may also be intrinsic, such as strictures or valves, or extrinsic, such as prostatic pathology.

Although patients usually present with signs |

or symptoms, |

hydronephrosis |

can be |

an incidental finding encountered during the |

evaluation of |

an unrelated |

process. |

210

Hydronephrosis that occurs acutely with sudden onset (for example, due to a renal calculus) can cause intense pain in the flank area, while a chronic occurrence that develops gradually will present with no pain or attacks of a dull discomfort. Nausea and vomiting may also occur. An obstruction that occurs at the urethra or bladder outlet can cause pain and pressure resulting from distension of the bladder. Blocking the flow of urine will commonly result in urinary tract infections which can lead to the development of additional stones, fever, and blood or pus in the urine. If complete obstruction occurs, kidney failure may follow.

If unrecognized or left untreated, hydronephrosis/hydroureter secondary to obstruction can lead to hypertension, loss of renal function, and sepsis. Consequently, patients found to have hydronephrosis or hydroureter should undergo a thorough evaluation. The specific treatment of a patient with hydronephrosis depends on the aetiology of the process, with any signs of infection within the obstructed system warranting urgent intervention (as infection of an obstructed system may progress rapidly to sepsis).

KEY POINTS

•The appearances of hydronephrosis on ultrasound or CT are of a dilated renal pelvis and calyceal system.

•A multitude of causes exist, with classification made according to the level within the urinary tract and whether the aetiology is intrinsic, extrinsic or functional.

•Treatment of hydronephrosis focuses upon the removal of the obstruction and/or drainage of the urine that has accumulated behind the obstruction.

•Any sign of infection within an obstructed system should prompt urgent intervention.

211