- •Public Administration And Public Policy

- •Contents

- •Acknowledgments

- •About The Authors

- •Comments On Purpose and Methods

- •Contents

- •1.1 Introduction

- •1.2 Culture

- •1.3 Colonial Legacies

- •1.3.1 British Colonial Legacy

- •1.3.2 Latin Legacy

- •1.3.3 American Legacy

- •1.4 Decentralization

- •1.5 Ethics

- •1.5.1 Types of Corruption

- •1.5.2 Ethics Management

- •1.6 Performance Management

- •1.6.2 Structural Changes

- •1.6.3 New Public Management

- •1.7 Civil Service

- •1.7.1 Size

- •1.7.2 Recruitment and Selection

- •1.7.3 Pay and Performance

- •1.7.4 Training

- •1.8 Conclusion

- •Contents

- •2.1 Introduction

- •2.2 Historical Developments and Legacies

- •2.2.1.1 First Legacy: The Tradition of King as Leader

- •2.2.1.2 Second Legacy: A Tradition of Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.1.3 Third Legacy: Traditions of Hierarchy and Clientelism

- •2.2.1.4 Fourth Legacy: A Tradition of Reconciliation

- •2.2.2.1 First Legacy: The Tradition of Bureaucratic Elites as a Privileged Group

- •2.2.2.2 Second Legacy: A Tradition of Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.2.3 Third Legacy: The Practice of Staging Military Coups

- •2.2.2.4 Fourth Legacy: A Tradition for Military Elites to be Loyal to the King

- •2.2.3.1 First Legacy: Elected Politicians as the New Political Boss

- •2.2.3.2 Second Legacy: Frequent and Unpredictable Changes of Political Bosses

- •2.2.3.3 Third Legacy: Politicians from the Provinces Becoming Bosses

- •2.2.3.4 Fourth Legacy: The Problem with the Credibility of Politicians

- •2.2.4.1 First Emerging Legacy: Big Businessmen in Power

- •2.2.4.2 Second Emerging Legacy: Super CEO Authoritarian Rule, Centralization, and Big Government

- •2.2.4.3 Third Emerging Legacy: Government must Serve Big Business Interests

- •2.2.5.1 Emerging Legacy: The Clash between Governance Values and Thai Realities

- •2.2.5.2 Traits of Governmental Culture Produced by the Five Masters

- •2.3 Uniqueness of the Thai Political Context

- •2.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •Appendix A

- •Contents

- •3.1 Thailand Administrative Structure

- •3.2 History of Decentralization in Thailand

- •3.2.1 Thailand as a Centralized State

- •3.2.2 Towards Decentralization

- •3.3 The Politics of Decentralization in Thailand

- •3.3.2 Shrinking Political Power of the Military and Bureaucracy

- •3.4 Drafting the TAO Law 199421

- •3.5 Impacts of the Decentralization Reform on Local Government in Thailand: Ongoing Challenges

- •3.5.1 Strong Executive System

- •3.5.2 Thai Local Political System

- •3.5.3 Fiscal Decentralization

- •3.5.4 Transferred Responsibilities

- •3.5.5 Limited Spending on Personnel

- •3.5.6 New Local Government Personnel System

- •3.6 Local Governments Reaching Out to Local Community

- •3.7 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Corruption: General Situation in Thailand

- •4.2.1 Transparency International and its Corruption Perception Index

- •4.2.2 Types of Corruption

- •4.3 A Deeper Look at Corruption in Thailand

- •4.3.1 Vanishing Moral Lessons

- •4.3.4 High Premium on Political Stability

- •4.4 Existing State Mechanisms to Fight Corruption

- •4.4.2 Constraints and Limitations of Public Agencies

- •4.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.2 History of Performance Management

- •5.2.1 National Economic and Social Development Plans

- •5.2.2 Master Plan of Government Administrative Reform

- •5.3 Performance Management Reform: A Move Toward High Performance Organizations

- •5.3.1 Organization Restructuring to Increase Autonomy

- •5.3.2 Process Improvement through Information Technology

- •5.3.3 Knowledge Management Toward Learning Organizations

- •5.3.4 Performance Agreement

- •5.3.5 Challenges and Lessons Learned

- •5.3.5.1 Organizational Restructuring

- •5.3.5.2 Process Improvement through Information Technology

- •5.3.5.3 Knowledge Management

- •5.3.5.4 Performance Agreement

- •5.4.4 Outcome of Budgeting Reform: The Budget Process in Thailand

- •5.4.5 Conclusion

- •5.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •6.1.1 Civil Service Personnel

- •6.1.2 Development of the Civil Service Human Resource System

- •6.1.3 Problems of Civil Service Human Resource

- •6.2 Recruitment and Selection

- •6.2.1 Main Feature

- •6.2.2 Challenges of Recruitment and Selection

- •6.3.1 Main Feature

- •6.4.1 Main Feature

- •6.4.2 Salary Management

- •6.4.2.2 Performance Management and Salary Increase

- •6.4.3 Position Allowance

- •6.4.5 National Compensation Committee

- •6.4.6 Retirement and Pension

- •6.4.7 Challenges in Compensation

- •6.5 Training and Development

- •6.5.1 Main Feature

- •6.5.2 Challenges of Training and Development in the Civil Service

- •6.6 Discipline and Merit Protection

- •6.6.1 Main Feature

- •6.6.2 Challenges of Discipline

- •6.7 Conclusion

- •References

- •English References

- •Contents

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Setting and Context

- •7.3 Malayan Union and the Birth of the United Malays National Organization

- •7.4 Post Independence, New Economic Policy, and Malay Dominance

- •7.5 Centralization of Executive Powers under Mahathir

- •7.6 Administrative Values

- •7.6.1 Close Ties with the Political Party

- •7.6.2 Laws that Promote Secrecy, Continuing Concerns with Corruption

- •7.6.3 Politics over Performance

- •7.6.4 Increasing Islamization of the Civil Service

- •7.7 Ethnic Politics and Reforms

- •7.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •8.1 Introduction

- •8.2 System of Government in Malaysia

- •8.5 Community Relations and Emerging Recentralization

- •8.6 Process Toward Recentralization and Weakening Decentralization

- •8.7 Reinforcing Centralization

- •8.8 Restructuring and Impact on Decentralization

- •8.9 Where to Decentralization?

- •8.10 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Ethics and Corruption in Malaysia: General Observations

- •9.2.1 Factors of Corruption

- •9.3 Recent Corruption Scandals

- •9.3.1 Cases Involving Bureaucrats and Executives

- •9.3.2 Procurement Issues

- •9.4 Efforts to Address Corruption and Instill Ethics

- •9.4.1.1 Educational Strategy

- •9.4.1.2 Preventive Strategy

- •9.4.1.3 Punitive Strategy

- •9.4.2 Public Accounts Committee and Public Complaints Bureau

- •9.5 Other Efforts

- •9.6 Assessment and Recommendations

- •9.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •10.1 History of Performance Management in the Administrative System

- •10.1.1 Policy Frameworks

- •10.1.2 Organizational Structures

- •10.1.2.1 Values and Work Ethic

- •10.1.2.2 Administrative Devices

- •10.1.2.3 Performance, Financial, and Budgetary Reporting

- •10.2 Performance Management Reforms in the Past Ten Years

- •10.2.1 Electronic Government

- •10.2.2 Public Service Delivery System

- •10.2.3 Other Management Reforms

- •10.3 Assessment of Performance Management Reforms

- •10.4 Analysis and Recommendations

- •10.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Malaysian Civil Service

- •11.2.1 Public Service Department

- •11.2.2 Public Service Commission

- •11.2.3 Recruitment and Selection

- •11.2.4 Malaysian Administrative Modernization and Management Planning Unit

- •11.2.5 Administrative and Diplomatic Service

- •11.4 Civil Service Pension Scheme

- •11.5 Civil Service Neutrality

- •11.6 Civil Service Culture

- •11.7 Reform in the Malaysian Civil Service

- •11.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.2.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.3.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.3.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.4.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.4.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.5.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.5.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.6.1 Context and Driving Force of Development

- •12.6.2 Major Institutional Development

- •12.7 Public Administration and Society

- •12.7.1 Public Accountability and Participation

- •12.7.2 Administrative Values

- •12.8 Societal and Political Challenge over Bureaucratic Dominance

- •12.9 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •13.1 Introduction

- •13.3 Constitutional Framework of the Basic Law

- •13.4 Changing Relations between the Central Authorities and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- •13.4.1 Constitutional Dimension

- •13.4.1.1 Contending Interpretations over the Basic Law

- •13.4.1.3 New Constitutional Order in the Making

- •13.4.2 Political Dimension

- •13.4.2.3 Contention over Political Reform

- •13.4.3 The Economic Dimension

- •13.4.3.1 Expanding Intergovernmental Links

- •13.4.3.2 Fostering Closer Economic Partnership and Financial Relations

- •13.4.3.3 Seeking Cooperation and Coordination in Regional and National Development

- •13.4.4 External Dimension

- •13.5 Challenges and Prospects in the Relations between the Central Government and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

- •References

- •Contents

- •14.1 Honesty, Integrity, and Adherence to the Law

- •14.2 Accountability, Openness, and Political Neutrality

- •14.2.1 Accountability

- •14.2.2 Openness

- •14.2.3 Political Neutrality

- •14.3 Impartiality and Service to the Community

- •14.4 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •15.1 Introduction

- •15.2 Brief Overview of Performance Management in Hong Kong

- •15.3.1 Measuring and Assessing Performance

- •15.3.2 Adoption of Performance Pledges

- •15.3.3 Linking Budget to Performance

- •15.3.4 Relating Rewards to Performance

- •15.4 Assessment of Outcomes of Performance Management Reforms

- •15.4.1 Are Departments Properly Measuring their Performance?

- •15.4.2 Are Budget Decisions Based on Performance Results?

- •15.4.5 Overall Evaluation

- •15.5 Measurability of Performance

- •15.6 Ownership of, and Responsibility for, Performance

- •15.7 The Politics of Performance

- •15.8 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Structure of the Public Sector

- •16.2.1 Core Government

- •16.2.2 Hybrid Agencies

- •16.2.4 Private Businesses that Deliver Public Services

- •16.3 Administrative Values

- •16.4 Politicians and Bureaucrats

- •16.5 Management Tools and their Reform

- •16.5.1 Selection

- •16.5.2 Performance Management

- •16.5.3 Compensation

- •16.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •17.1 Introduction

- •17.2 The Philippines: A Brief Background

- •17.4 Philippine Bureaucracy during the Spanish Colonial Regime

- •17.6 American Colonial Regime and the Philippine Commonwealth

- •17.8 Independence Period and the Establishment of the Institute of Public Administration

- •17.9 Administrative Values in the Philippines

- •17.11 Conclusions

- •References

- •Contents

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Toward a Genuine Local Autonomy and Decentralization in the Philippines

- •18.2.1 Evolution of Local Autonomy

- •18.2.2 Government Structure and the Local Government System

- •18.2.3 Devolution under the Local Government Code of 1991

- •18.2.4 Local Government Finance

- •18.2.5 Local Government Bureaucracy and Personnel

- •18.3 Review of the Local Government Code of 1991 and its Implementation

- •18.3.1 Gains and Successes of Decentralization

- •18.3.2 Assessing the Impact of Decentralization

- •18.3.2.1 Overall Policy Design

- •18.3.2.2 Administrative and Political Issues

- •18.3.2.2.1 Central and Sub-National Role in Devolution

- •18.3.2.2.3 High Budget for Personnel at the Local Level

- •18.3.2.2.4 Political Capture by the Elite

- •18.3.2.3 Fiscal Decentralization Issues

- •18.3.2.3.1 Macroeconomic Stability

- •18.3.2.3.2 Policy Design Issues of the Internal Revenue Allotment

- •18.3.2.3.4 Disruptive Effect of the Creation of New Local Government Units

- •18.3.2.3.5 Disparate Planning, Unhealthy Competition, and Corruption

- •18.4 Local Governance Reforms, Capacity Building, and Research Agenda

- •18.4.1 Financial Resources and Reforming the Internal Revenue Allotment

- •18.4.3 Government Functions and Powers

- •18.4.6 Local Government Performance Measurement

- •18.4.7 Capacity Building

- •18.4.8 People Participation

- •18.4.9 Political Concerns

- •18.4.10 Federalism

- •18.5 Conclusions and the Way Forward

- •References

- •Annexes

- •Contents

- •19.1 Introduction

- •19.2 Control

- •19.2.1 Laws that Break Up the Alignment of Forces to Minimize State Capture

- •19.2.2 Executive Measures that Optimize Deterrence

- •19.2.3 Initiatives that Close Regulatory Gaps

- •19.2.4 Collateral Measures on Electoral Reform

- •19.3 Guidance

- •19.3.1 Leadership that Casts a Wide Net over Corrupt Acts

- •19.3.2 Limiting Monopoly and Discretion to Constrain Abuse of Power

- •19.3.3 Participatory Appraisal that Increases Agency Resistance against Misconduct

- •19.3.4 Steps that Encourage Public Vigilance and the Growth of Civil Society Watchdogs

- •19.3.5 Decentralized Guidance that eases Log Jams in Centralized Decision Making

- •19.4 Management

- •19.5 Creating Virtuous Circles in Public Ethics and Accountability

- •19.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •20.1 Introduction

- •20.2 Problems and Challenges Facing Bureaucracy in the Philippines Today

- •20.3 Past Reform Initiatives of the Philippine Public Administrative System

- •20.4.1 Rebuilding Institutions and Improving Performance

- •20.4.1.1 Size and Effectiveness of the Bureaucracy

- •20.4.1.2 Privatization

- •20.4.1.3 Addressing Corruption

- •20.4.1.5 Improving Work Processes

- •20.4.2 Performance Management Initiatives for the New Millennium

- •20.4.2.1 Financial Management

- •20.4.2.2 New Government Accounting System

- •20.4.2.3 Public Expenditure Management

- •20.4.2.4 Procurement Reforms

- •20.4.3 Human Resource Management

- •20.4.3.1 Organizing for Performance

- •20.4.3.2 Performance Evaluation

- •20.4.3.3 Rationalizing the Bureaucracy

- •20.4.3.4 Public Sector Compensation

- •20.4.3.5 Quality Management Systems

- •20.4.3.6 Local Government Initiatives

- •20.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •21.1 Introduction

- •21.2 Country Development Context

- •21.3 Evolution and Current State of the Philippine Civil Service System

- •21.3.1 Beginnings of a Modern Civil Service

- •21.3.2 Inventory of Government Personnel

- •21.3.3 Recruitment and Selection

- •21.3.6 Training and Development

- •21.3.7 Incentive Structure in the Bureaucracy

- •21.3.8 Filipino Culture

- •21.3.9 Bureaucratic Values and Performance Culture

- •21.3.10 Grievance and Redress System

- •21.4 Development Performance of the Philippine Civil Service

- •21.5 Key Development Challenges

- •21.5.1 Corruption

- •21.6 Conclusion

- •References

- •Annexes

- •Contents

- •22.1 Introduction

- •22.2 History

- •22.3 Major Reform Measures since the Handover

- •22.4 Analysis of the Reform Roadmap

- •22.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •23.1 Decentralization, Autonomy, and Democracy

- •23.3.1 From Recession to Take Off

- •23.3.2 Politics of Growth

- •23.3.3 Government Inertia

- •23.4 Autonomy as Collective Identity

- •23.4.3 Social Group Dynamics

- •23.5 Conclusion

- •References

- •Contents

- •24.1 Introduction

- •24.2 Functions and Performance of the Commission Against Corruption of Macao

- •24.2.1 Functions

- •24.2.2 Guidelines on the Professional Ethics and Conduct of Public Servants

- •24.2.3 Performance

- •24.2.4 Structure

- •24.2.5 Personnel Establishment

- •24.3 New Challenges

- •24.3.1 The Case of Ao Man Long

- •24.3.2 Dilemma of Sunshine Law

- •24.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •Appendix A

- •Contents

- •25.1 Introduction

- •25.2 Theoretical Basis of the Reform

- •25.3 Historical Background

- •25.4 Problems in the Civil Service Culture

- •25.5 Systemic Problems

- •25.6 Performance Management Reform

- •25.6.1 Performance Pledges

- •25.6.2 Employee Performance Assessment

- •25.7 Results and Problems

- •25.7.1 Performance Pledge

- •25.7.2 Employee Performance Assessment

- •25.8 Conclusion and Future Development

- •References

- •Contents

- •26.1 Introduction

- •26.2 Civil Service System

- •26.2.1 Types of Civil Servants

- •26.2.2 Bureaucratic Structure

- •26.2.4 Personnel Management

- •26.4 Civil Service Reform

- •26.5 Conclusion

- •References

172 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

(TI), indicate that reforms have failed to bolster accountability and address corruption within the public sector. This chapter discusses ethics and corruption in the Malaysian civil service, and efforts to combat them. It also investigates the factors of corruption with recent scandals and anomalies of political patronage and networks resulting in inefficiencies and ineffectiveness of bureaucracy, policies, and procurements in a political system. This chapter analyzes the distortion and mismanagement in administration resulting from corruption, a controversial issue. Some observations are highlighted with regard to the issues of ethics and corruption in Malaysia, which implies administrative inefficiency and political clientelism in the system of governance. Yet, many anti-corruption measures and legislations have been fostered over the years with the setting up of various laws and institutions, a step in the right direction, to reconstruct the system and control the damage of corruption, only resulting in marginal changes. Assessments and propositions for change paradigms to rethink the issue of patronage and respond to an evident problem of corruption constitute the latter part of this chapter. Nonetheless, the policy of controlling and reducing corruption is a continuing challenge and an imperative concern for the government in promising better governance and performance of institutions and public servants that serve as mechanisms of accountability to the state and its citizens.

9.2 Ethics and Corruption in Malaysia: General Observations

Prior to independence, the legal provision on corruption was the enactment of the Prevention of Corruption Ordinance in 1950. This ordinance was later replaced by the Prevention of Corruption Act 1961, which was amended twice in 1967 and 1971. The 1967 amendment increased the powers of the public prosecutor in the conduct of investigations, and members of public bodies and legislators are legally obliged to make reports of corruption, whereas the 1971 amendment concerned the definition of “offence under the Act.”

In Malaysia, graft is defined in the Prevention of Corruption Act 1961 and similarly in the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission Bill 2008, which comes into operation in 2009 as (a) money or any gift, loan, fee, reward, valuable security, or other property or interest in property of any description, whether movable or immovable; (b) any office, dignity, employment, contract or services, and any agreement to give employment or render services in any capacity; (c) any payment, release, discharge or liquidation of any loan, obligation or other liability whatsoever, whether in whole or in part; (d) any valuable consideration of any kind, any discount, commission, rebate, bonus, deduction, or percentage; (e) any forbearance to demand any money or money’s worth or valuable thing; (f) any aid, vote, consent or influence, or pretended aid, vote, consent or influence, any promise or procurement of, or agreement or endeavor to procure, or the holding out of any expectation of, any gift, loan, fee, reward, consideration, or gratification within the meaning of this paragraph; (g) any other service, favor or advantage of any description whatsoever, including protection from any penalty or disability incurred or apprehended or from any action or proceedings of a disciplinary or penal nature, whether or not already instituted, and including the exercise or the forbearance from the exercise of any right or any official power or duty; and (h) any offer, undertaking, or promise of any gratification within the meaning of paragraphs (a) to (g). It was subsequently repealed and replaced with the Prevention of Corruption Act 1997 to include bribery, false claims, and the use of public position or office for pecuniary or other advantages.

In a recent TI Global Corruption Barometer (GCB) 2009, Malaysia was ranked 56th with a score of 4.5 and, respectively, in 2008 at 47th and 43rd place in 2007. For 2006, Malaysia

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

Public Ethics and Corruption in Malaysia 173

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

65 |

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

60 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

55 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CPI Score |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

50 |

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

45 |

Rank |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

40 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

35 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

20 |

|

|

|

2006 |

|

||||||||||

|

CPI Score |

5.3 |

5 |

5.3 |

5.1 |

4.8 |

5 |

4.9 |

5.2 |

5 |

5.1 |

5 |

|

|

Score of Median |

5 |

5.3 |

4.2 |

3.8 |

4.1 |

4 |

3.8 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

|

|

Rank |

26 |

32 |

29 |

32 |

36 |

36 |

33 |

37 |

39 |

39 |

44 |

|

|

Rank percentile-th |

48.1 |

61.5 |

34.1 |

32.3 |

40 |

39.6 |

32.4 |

27.8 |

26.9 |

24.5 |

27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Year |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CPI Score |

|

|

|

Score of Median |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rank |

|

|

|

Rank percentile-th |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 9.1 Transparency Index of Malaysia (1996–2006). (Source: Transparency International.)

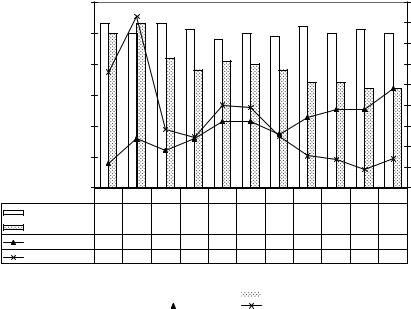

was ranked 43rd out of the 180 nations polled. Malaysia had a score of 5.1 points, just above the fi ve cut-off points of countries with and without serious corruption problems. The level of effectiveness in fi ghting corruption has not improved for over 8 years; Malaysia still trails behind many countries such as neighboring Singapore (ranked 3rd for the past 2 years) and Hong Kong (in 12th position in 2009). The GCB, carried out by Gallup International Association on behalf of TI, interviewed 63,199 respondents in 60 countries between June and September. In Malaysia, the survey was conducted from July 2 till August 5, 2008, involving 1250 people from the urban areas in Peninsular Malaysia who were interviewed face-to-face. It was found that 53% of those surveyed said the government was effective in fi ghting corruption, but 63% anticipated that the future may not be promising with further increases in cases. According to the survey, the police were perceived to be the most corrupt, followed by political parties, registry and licensing services, business or private sector, parliament or legislature, legal system or judiciary, tax revenue, and media. In the 2009 GCB, 42% of Malaysians said that political parties are the most corrupt institution, followed closely by the civil service at 37%. Figure 9.1 shows the Transparency Index of Malaysia, depicting Malaysia’s CPI score for the past 11 years (1996–2006) conducted by TI. Malaysia’s CPI score and rank were also compared to the overall performance of participant countries. The average CPI score for Malaysia is 5.06, and 10 is the maximum score for least corruption. Malaysia’s score fluctuated around 4.8 (worst) to 5.3 (best) and stagnant around 5.0–5.1. On the surface, the CPI rank for Malaysia seemed to be deteriorating across time, especially in recent years (26 in 1996 to 44 in 2006). However, the number of countries that participated in this survey also increased across the time (54 countries in 1996 to 163 countries in 2006).

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

174 Public Administration in Southeast Asia

9.2.1 Factors of Corruption

The perceived level of corruption in Malaysia and across many countries is attributed to the absence of independent and effective law enforcement despite the public expectation that civil servants are to serve with full commitment and impartiality in addition to the anticorruption laws and measures in existence contributing to varying levels of effectiveness. The degree of corruption especially among the elites of society comprising politicians, businessmen, and certain segments of the civil service is considerable, even though there have been significant controls experienced in the country.

A feature of the Malaysian public bureaucracy is the connection and close ties between leading politicians and bureaucrats. Owing to the power position of the Malaysian bureaucratic elite and political elite, the Malaysian bureaucracy “enjoys a position of power perhaps unequaled by any other civil service in a democratic country” [1]. Patronage may work well when government is small, but growth and development in a democratizing country may progressively become more corrupt and inefficient. This could imply the coexistence of administrative inefficiency and political clientelism in the administration.

In addition, a persistent problem is the lack of transparency. Concern for secrecy prevents leakage of government secrets that forbid the release of information to the public. The formulation of legal restrictions such as the Sedition Act in 1948 (revised 1969), the Internal Security Act (ISA) in 1960 (revised 1988), and the Official Secrets Act have discouraged many from disclosing information to concerned citizens and interests groups. It means that government officials are prohibited from disclosing government information as one could be charged under the Official Secrets Act. There is much at stake as one could lose his/her job, pension, and gratuity benefits in addition to imprisonment of not less than 1 year but not exceeding 14 years. Further, no individual can be in possession of any classified documents as the penalty is similar. The Official Secrets Act 1972 (Act 88), which was amended in 1986, has been criticized for its regular and indiscriminate use in reducing transparency in the government’s working procedures and in reducing access to documents that are deemed important in the public domain. In this respect, the documents include cabinet documents, records of decisions and deliberations including those of Cabinet and State Executive Council Committees, State Executive Council documents, and those of national security, defense, and international relations. This means that a wide range of documents are not available for public view, particularly information of public interest. With such restrictions, many wrongdoings are difficult to expose, as evident in procurement issues and contractual agreements.

A criticism frequently made is that many of the arrests in corruption cases only involved the “small fish” (lower-level officials) and the “big fish” (syndicates, influential top bureaucrats, businessmen, and politicians) appeared unscathed. This is attributed to the government’s failure to eradicate corruption due to lack of independence despite increasing pressure from the public and the government’s assurance that corruption will be dealt with more seriously.

The common perception is that there may be little one can do about corruption particularly when it is embedded in the work systems and coexisting, the indifferent, powerful individuals who find the acts inevitable though offensive but profess innocence. Ineffective anti-corruption strategy and control of corrupt behavior among civil servants and political leaders have not been able to remove the opportunities for corruption because of lack of political commitment and the ineffectiveness of the measures. The penalties for corrupt offences have not been prevalent as there seems to be a low probability of detecting corrupt offences and consequently the rewards for corruption are higher than the punishment for corrupt offenders.

© 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC