Wilkinson. Essential Neurology 2005

.pdf

230 |

CHAPTER 14 |

Causes of dementia

The commoner causes of dementia are listed below, followed by brief notes about each of the individual causes.

1.Alzheimer’s disease.

2.Dementia with Lewy bodies.

3.Vascular dementia.

4.Other progressive intracranial pathology:

•brain tumour;

•chronic subdural haematoma;

•chronic hydrocephalus;

•multiple sclerosis;

•Huntington’s disease;

•Pick’s disease;

•motor neurone disease;

•Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.

5.Alcohol and drugs.

6.Rare infections, deficiencies, etc.:

•HIV–AIDS;

•syphilis;

•B vitamin deficiency;

•hypothyroidism.

Alzheimer’s disease

This is very common, especially with increasing age, and accounts for about 65% of dementia in the UK. Onset and progression are insidious. Memory is usually affected first, followed by language and spatial abilities. Insight and judgement are preserved to begin with. After a few years all aspects of intellectual function are affected and the patient may become frail and unsteady. Epilepsy is uncommon.

The main pathology is in the cerebral cortex, initially in the temporal lobe, with loss of synapses and cells, neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques. These changes also affect subcortical nuclei, including the ones that provide acetylcholine to the cerebral cortex. This may contribute to the cognitive decline; cholinesterase inhibitors such as rivastigmine and donepezil sometimes provide symptomatic improvement.

People with the apolipoprotein E e4 genotype are at increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, and mutations in the amyloid precursor protein gene and the presenilin genes can cause familial Alzheimer’s disease. Environmental factors are probably also important.

Atrophy of both temporal lobes due to Alzheimer’s disease.

DEMENTIA

Key features of Lewy body dementia

•Dementia

•Parkinsonism

•Visual hallucinations

•Flucuating cognitive impairment

231

Dementia with Lewy bodies

Dementia with Lewy bodies accounts for about 15% of dementia in the UK. The intellectual symptoms are similar to those of Alzheimer’s disease but patients are much more likely to develop parkinsonism, visual hallucinations and episodes of confusion.

The distribution of pathology is also similar, but affected neurones form Lewy bodies rather than tangles. The cholinergic deficit is more profound, and the response to cholinesterase therapies usually more marked. Neuroleptic drugs can exacerbate the parkinsonism to a severe, or even fatal, degree.

Vascular dementia (see also p. 31)

This accounts for about 10% of UK dementia. Most cases are caused by widespread small vessel disease within the brain itself, due to hypertension or diabetes, giving rise to extensive and diffuse damage to the subcortical white matter. These patients present with failing judgement and reasoning, followed by impaired memory and language, together with a complex gait disturbance, consisting of small shuffling steps (marche à petits pas). Emotional lability and pseudobulbar palsy are often present, with a brisk jaw-jerk and spastic dysarthria.

A few cases are due to carotid atheroma giving rise to multiple discrete cerebral infarcts, i.e. multi-infarct dementia. These patients have a stepwise evolution with events that can be recognized as distinct strokes and which give rise to focal neurological deficits (such as hemiparesis, dysphasia or visual field defect). Intellectual impairment accrues as these deficits start to summate.

Treatment of vascular risk factors, especially hypertension and hyperlipidaemia, can have a useful preventive effect in both forms of vascular dementia.

Extensive signal change in the white matter due to small vessel disease.

232 |

CHAPTER 14 |

Other progressive intracranial pathology

Frontal and temporal tumours occasionally become large enough to cause significant intellectual impairment before producing tell-tale features like epilepsy, focal deficit or raised intracranial pressure.

Patients with chronic subdural haematoma are usually elderly, alcoholic or anticoagulated. They may not recall the causative head injury, but become drowsy, unsteady and intellectually impaired over a few weeks. Because the collection of blood is outside the brain, focal neurological signs appear late.

Any process which causes hydrocephalus slowly may declare itself by failing intellectual ability, slowness, inappropriate behaviour and drowsiness, often with gait disturbance, incontinence of urine and headache.

Neurosurgery may help all these patients.

Severe multiple sclerosis can cause dementia, often with emotional lability.

Dementia that particularly affects frontal lobe functions, with disinhibited and illogical behaviour, is characteristic of Huntington’s disease, the dementia that sometimes accompanies motor neurone disease, and Pick’s disease. This pattern of dementia, where language and spatial abilities are affected late, if at all, is particularly challenging to manage. The patient has no insight into the nature of his problems, often neglects himself and refuses help.

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) classically causes a very rapidly progressive and devastating dementia with ataxia and myoclonic jerks. The patient gets worse day by day and is helpless and bed-bound within weeks or months, dying within a year. It is mercifully very rare.

CT scan demonstrating a frontal meningioma with surrounding cerebral oedema. The tumour enhances after contrast administration (right-side image).

Severe atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes due to Pick’s disease.

DEMENTIA |

233 |

Transmission and CJD

There are two aspects to mention:

1.Whereas most cases of classic CJD are caused by spontaneous deposition of an abnormal form of prion protein within the patient’s brain, a few cases have been caused by iatrogenic, person to person, transmission of this abnormal protein through pituitary extracts, corneal grafts and neurosurgical procedures.

2.The variant form of CJD, which occurs mainly in the UK, takes a slightly slower course and affects younger people. It is thought to be due to transmission of the closely related prion disease in cattle, bovine spongiform encephalopathy, to people by human consumption of contaminated beef.

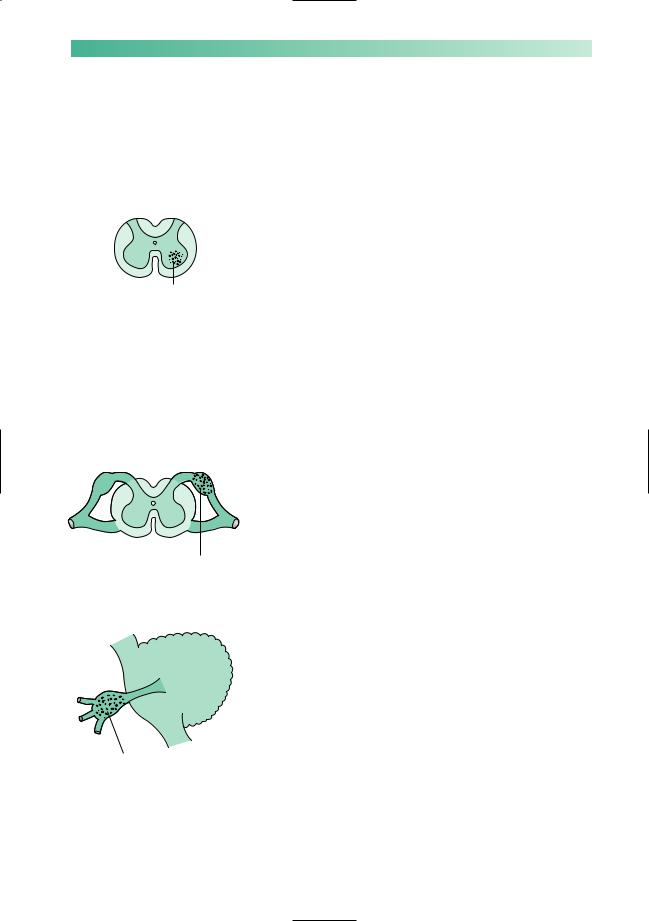

Frontal toxoplasmosis abscess due to HIV–AIDS.

Alcohol and drugs

In addition to the rather flamboyant syndromes seen in alcoholics who become deficient in vitamin B1, namely Wernicke’s encephalopathy and Korsakoff’s psychosis, it is being increasingly recognized that chronic alcoholism is associated with cerebral atrophy and generalized dementia.

Patients, especially those who are elderly, may become confused and forgetful whilst on medication, especially antidepressants, tranquillizers, hypnotics, analgesics and anticonvulsants.

It is most important to bear in mind alcohol and drugs before embarking upon a detailed investigation of dementia.

Rare infections, deficiencies and metabolic disorders

HIV–AIDS

HIV–AIDS can cause dementia, either through a primary HIV encephalitis or through the CNS complications of immunodeficiency such as opportunistic infection (toxoplasmosis, cryptococcal meningitis) and lymphoma. The risk of all of these is greatly reduced by current highly active retroviral therapy regiments, but tragically these are least available in the countries with the greatest prevalence and need.

Tertiary syphilis

Tertiary syphilis was the AIDS of the nineteenth century but is now rare because of improvements in public health and the widespread use of penicillin, which is lethal to the spirochaete Treponema pallidum. It gives rise to general paralysis of the insane (a dementia with prominent frontal lobe features), tabes dorsalis (with loss of proprioception and reflexes in the lower limbs), taboparesis (a mixture of the two) and meningovascular syphilis (with small vessel strokes, especially of the brainstem) (see p. 248 for further details). Blood tests for syphilis should be a routine part of the investigation of dementia.

234

B vitamin deficiency

Vitamin B1 deficiency in Western society occurs in alcoholics whose diet is inadequate, and in people who voluntarily modify their diet to an extreme degree, e.g. patients with anorexia nervosa or extreme vegetarians.

Impairment of short-term memory, confusion, abnormalities of eye movement and pupils, together with ataxia, constitute the features of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Though associated with demonstrable pathology in the midbrain, this syndrome is often rapidly reversible by urgent intravenous thiamine replacement.

Less reversible is the chronic state of short-term memory impairment and confabulation which characterize Korsakoff’s psychosis, mainly seen in advanced alcoholism.

Whether vitamin B12 deficiency causes dementia remains uncertain. Certainly, peripheral neuropathy and subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord are more definite neurological consequences of deficiency in this vitamin.

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is usually rather evident clinically by the time significant impairment of intellectual function is present. It is a cause worth remembering in view of its obvious reversibility.

Investigation of dementia

Usually an accurate history, with collateral information from family and friends, together with a full physical examination, will highlight the most likely cause for an individual patient’s dementia.

It is worth thinking whether the problem has begun in the temporal and parietal lobes (with poor memory, then language and spatial problems, usually indicatingAlzheimer’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies) or in the frontal lobes (with changes in behaviour, raising the possibility of surgically treatable pathology like tumour or hydrocephalus). It is important to ask about the patient’s past medical history (vascular risk factors) and family history (vascular risk factors again, and genetic dementias such as Huntington’s disease, familial Alzheimer’s disease and Pick’s disease). It is particularly important to ask about the patient’s social circumstances, because of the need to provide support and care during an illness that is usually arduous and prolonged.

The examination must include tests of memory, language, spatial ability and reasoning as already outlined. It must include a search for neurological clues to the cause of the dementia (see table on opposite page), and a careful examination of the

CHAPTER 14

DEMENTIA |

235 |

Clinical clues to the cause of dementia

Myoclonus |

Neurodegenerative disease: usually Alzheimer’s or dementia with Lewy bodies but |

|

think of CJD if the myoclonus is severe |

Parkinsonism |

Dementia with Lewy bodies |

Focal deficit |

Tumour or vascular dementia |

Drowsiness |

Delirium not dementia; hydrocephalus; subdural haematoma |

Chaotic gait |

Vascular dementia; hydrocephalus; Huntington’s disease; syphilis; CJD |

|

|

mental state, looking for symptoms and signs of anxiety and depression that may be contributing to the clinical problem.

Bedside testing of intellectual function can be usefully supplemented by standardized neuropsychological testing; this is especially helpful in distinguishing between early dementia and the worried well.

Blood tests rarely detect treatable pathology, but should routinely include:

•full blood count and ESR;

•electrolytes, glucose, calcium and liver function tests;

•thyroid function tests;

•syphilis serology;

•vitamin B12;

•antinuclear antibody.

In selected cases these should be supplemented with more

specific tests, after appropriate counselling, such as HIV serology, genetic tests for Huntington’s disease and so on.

Brain imaging, with a CT scan to rule out tumour, hydrocephalus and vascular disease, is now routine in developed countries. MR brain scanning may be useful in delineating the rarer focal brain atrophies such as Pick’s disease and has a research role in monitoring disease progression. Other tests, such as CSF examination or pressure monitoring, are sometimes required.