Wilkinson. Essential Neurology 2005

.pdf

220

Atypical facial pain

Atypical facial pain causes a dull, persistent ache around one cheek with a great deal of accompanying misery. The pain is constant, not jabbing. Most patients are women aged between 30 and 50 years. Physical examination and investigations are normal. Like tension headaches, atypical facial pain is hard to relieve. Tricyclic antidepressants can, however, be curative.

Post-herpetic neuralgia

In the face and head, herpes zoster infection most commonly affects the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. The condition is painful during the acute vesicular phase and, in a small percentage of patients, the pain persists after the rash has healed. The occurrence of persistent pain, post-herpetic neuralgia, does not relate to the age of the patient or the severity of the acute episode, nor is it definitely reduced by the early use of antiviral agents.

Post-herpetic neuralgia can produce a tragic clinical picture. The patient is often elderly (since shingles is more common in the elderly) with a constant burning pain in the thinned and depigmented area that was affected by the vesicles. Not infrequently, the patient cannot sleep properly, loses weight and becomes very depressed.

The pain rarely settles of its own accord but can be ameliorated by tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin and topical capsaicin ointment. Capsaicin is a derivative of chilli pepper that suppresses activity in substance P-containing sensory neurones; care must be taken to keep it out of the eye.

CHAPTER 13

'I'm beginning to think I'm neurotic.'

'It's been there every day since I had the shingles.'

Post-concussion syndrome

Patients of any age who have an injury to their head resulting in concussion may suffer a group of symptoms during the months or years afterwards, even though physical examination and investigation are normal.

The head injury is usually definite but mild, with little or no post-traumatic amnesia. Subsequently, the patient may complain of headaches (which are frequent or constant and made worse by exertion), poor concentration and memory, difficulty in taking decisions, irritability, depression, dizziness, intolerance of alcohol and exercise.

The extent to which these symptoms are physical (and the mechanism of this) or psychological, and the extent to which they are maintained by the worry of medico-legal activity in relation to compensation, is not clear and probably varies a good deal from case to case.

'I've not been myself ever since that accident.'

HEADACHE AND FACIAL PAIN |

221 |

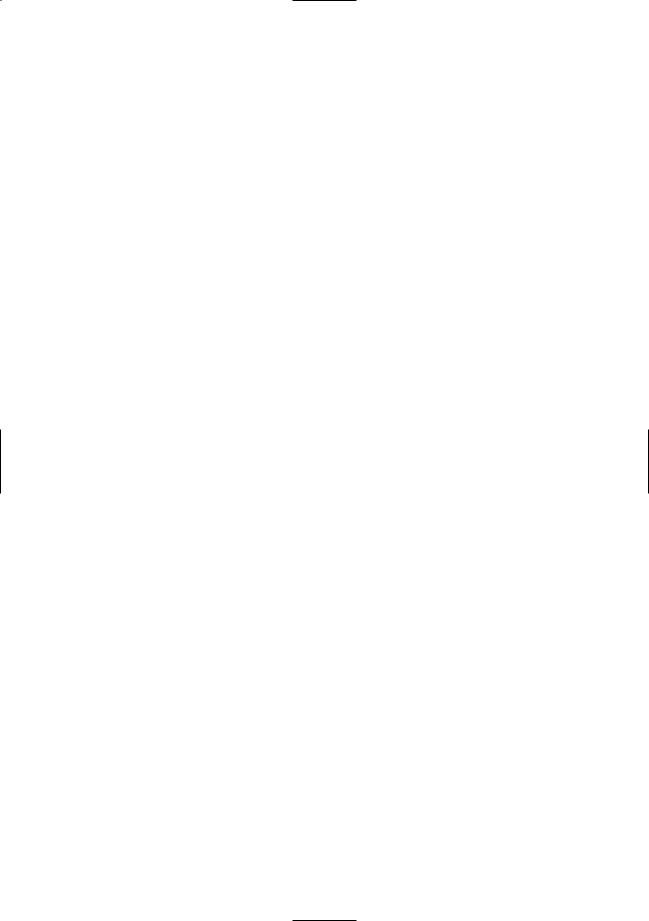

Other causes of headache and facial pain

It is important to remember that pains in the head and face may be non-neurological in nature, and more the province of the general practitioner or other medical or surgical specialists. Some of these conditions are very common. They are shown below.

Sinuses infection malignancy

Eyes eyestrain glaucoma uveitis

Temporo-mandibular joints arthritis

Ears

otitis media

Teeth malocclusion caries

Neck trauma

disc degenerative disease carotid dissection

Heart

angina may be felt in the neck and jaws

Fig. 13.1 Non-neurological causes of headache and facial pain.

222 |

CHAPTER 13 |

CASE HISTORIES

The diagnosis of headache and facial pains concentrates very much on the history. Abnormal examination findings are important but rare, except in the acute and evolving headaches. Patients often use key phrases which start to point you towards the correct diagnosis. In reality you would want to hear a great deal more before committing yourself to a diagnosis, but see if you can identify the likely causes in these cases.

a.‘It was like being hit on the back of the head with a baseball bat.’

b.‘It’s a tight band around my head, holding it in a vice, like something’s expanding inside.’

c.‘Every night at 2 o’clock, like someone is squeezing my eyeball very hard.’

d.‘Mainly in the mornings and when I bend over.’

e.‘All over my head, it feels so tender, I’ve never felt so bad in all my years.’

f.‘Maybe once or twice a month, at the front on this side.’

g.‘Cruel, sudden, I can’t brush my teeth.’

h.‘Awful when I sit up, fine lying flat.’

i.‘Endless, nagging ache in this cheek: I’m desperate.’

j.‘It’s very embarrassing, doctor, it always happens just as I’m, you know. . . .’

(For answers, see pp. 265–6.)

CHAPTER 14 |

14 |

Dementia |

Introduction

Dementia is a progressive loss of intellectual function. It is common in the developed world and is becoming more common as the age of the population gradually increases, putting more people at risk of neurodegenerative disease. In the developing world there are other serious causes, including the effects of HIV–AIDS and untreated hypertension. Patients with dementia place a major burden on their families and on medical and social services. Reversible causes of dementia are rare. Treatment is generally supportive or directed at relieving symptoms, and is usually far from perfect. But dementia is now an area of intense scientific study, bringing the prospect of more effective therapies in the future.

Recognizing dementia is easy when it is severe. It is much harder to distinguish early dementia from the forgetfulness due to anxiety, and from the mild cognitive impairment that often accompanies ageing (usually affecting memory for names and recent events), which does not necessarily progress to more severe disability. It is also important to distinguish dementia from four related but clinically distinct entities: delirium (or acute confusion), learning disability, pseudodementia and dysphasia.

Delirium

Delirium is a state of confusion in which patients are not fully in touch with their environment. They are drowsy, perplexed and uncooperative. They often appear to hallucinate, for example misinterpreting the pattern on the curtains as insects. There are many possible causes, including almost any systemic or CNS infection, hypoxia, drug toxicity, alcohol withdrawal, stroke, encephalitis and epilepsy. Patients with a pre-existing brain disease, including dementia, are particularly susceptible to delirium.

Dementia

•Progressive

•Involvement of more than one area of intellectual function (such as memory, language, judgement or visuospatial ability)

•Sufficiently severe to disrupt daily life

224

DEMENTIA |

225 |

Special

school

Learning disability

Learning disability is the currently accepted term for a condition that has in the past been referred to as mental retardation, mental handicap or educational subnormality. The difference between dementia and learning disability is that patients with dementia have had normal intelligence in their adult life and then start to lose it, whereas patients with learning disability have suffered some insult to their brains early in life (Fig. 14.1) which has prevented the development of normal intelligence. While dementia is progressive, learning disability is static unless a further insult to the brain occurs. The person with learning disability learns and develops, slowly and to a limited extent.

Early disruption of brain function results in any of:

1.Impaired thinking, reasoning, memory, language, etc.

2.Behaviour problems because of difficulty in learning social customs, controlling emotions or appreciating the emotional needs of others.

3.Abnormal movement of the body, because of damage to the parts of the brain involved in movement (motor cortex, basal ganglia, cerebellum, thalamus, sensory cortex) giving rise to:

•delayed milestones for sitting, crawling, walking;

•spastic forms of cerebral palsy including congenital hemiplegia and spastic diplegia (or tetraplegia);

•dystonic (‘athetoid’) form of cerebral palsy (where the intellect is often normal);

•clumsy, poorly coordinated movement;

•repetitive or ritualistic stereotyped movements.

4.Epilepsy, which may be severe and resistant to treatment.

It is now clear that in developed countries anoxic birth injury, once thought to account for most cases of learning disability and cerebral palsy, is actually an unusual cause; genetic disorders are the major culprit. Parents may appreciate early diagnosis, genetic counselling and in a few cases prenatal diagnosis.

|

Genetic abnormality |

|

Low IQ |

|

|

e.g. Down's syndrome |

|

|

|

|

Fragile X syndrome |

Young |

||

|

|

|

|

Movement |

|

Intra-uterine event |

|

|

disorder |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

e.g. Infection |

|

|

|

|

Stroke |

|

Epilepsy |

|

|

Drug exposure |

|

Brain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Birth anoxia |

|

Behaviour |

|

Fig. 14.1 Diagram to show the |

|

problems |

||

|

Insult early in life |

|||

common insults that can occur to |

|

|

e.g. Meningitis |

|

the developing brain, and their |

|

|

Head injury |

|

consequences. |

|

|

|

Non-accidental injury |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

226 |

CHAPTER 14 |

Pseudodementia

A few patients may deliberately affect loss of memory and impaired intellectual function, usually in response to a major life crisis. Anxiety commonly interferes with the ability to take in new information. In the main, however, pseudodementia refers to the impaired thinking that occurs in some patients with depression. Severely depressed patients may be mentally and physically retarded to a major degree. There may be long intervals between question and answer when interviewing such patients. The patient’s feelings of unworthiness and lack of confidence may be such that he is quite uncertain whether his thoughts and answers are accurate or of any value. Patients like this often state quite categorically that they cannot think or remember properly, and defer to their spouse when asked questions. Their overall functional performance, at work or in the house, may become grossly impaired because of mental slowness, indecisiveness, lack of enthusiasm and impaired energy.

'. . . I can't remember . . I think you'd better ask

my wife . .'

Dysphasia

The next clear discrimination is between dementia and dysphasia. It is very likely that talking to the patient, in an attempt to obtain details of the history, will have defined whether the problem is one of impaired intellectual function, or a problem of language comprehension and production, or both. The discrimination is important, not least because of the difficulty in assessing intellectual function in a patient with significant dysphasia. Moreover, dysphasia can be mistaken for delirium, leading to the neglect of a treatable focal brain problem such as encephalitis.

Patients with dysphasia have a language problem. This is not dissimilar to being in a foreign country and finding oneself unable to understand (receptive dysphasia), or make oneself understood (expressive dysphasia).

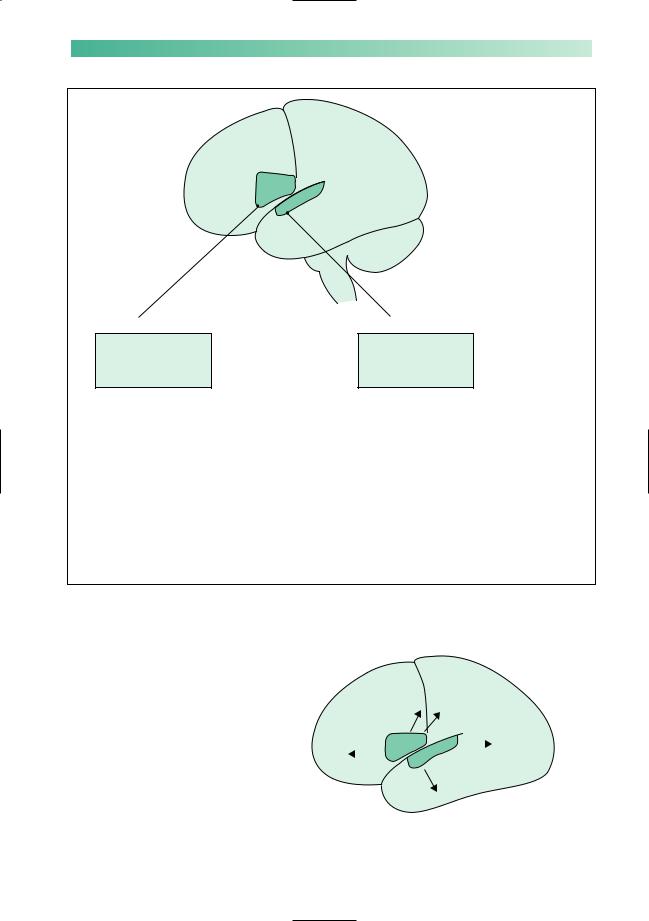

Figure 14.2 sets out the two main types of dysphasia (as seen in the majority of people, in whom speech is represented in the left cerebral hemisphere). Not infrequently, a patient has a lesion in the left cerebral hemisphere which is large enough to produce a global or mixed dysphasia. Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas are both involved; verbal expression and comprehension are both impaired.

Involvement of nearby areas of the brain by the lesion causing the dysphasia may result in other clinical features. These are shown in Fig. 14.3. Stroke, ischaemic or haemorrhagic, and cerebral tumour are the common sorts of focal pathology to behave in this way.

X

X

Language problem

DEMENTIA |

227 |

Broca's area

Motor dysphasia Expressive dysphasia Non-fluent dysphasia Anterior dysphasia

Wernicke's area

Sensory dysphasia Receptive dysphasia Fluent dysphasia Posterior dysphasia

The patient can understand spoken words normally. Other people's language is making appropriate sensible ideas in his brain. He is not able to find the words to express himself. Speech is non-fluent, hesitant, reduced, with grammatical errors and omissions. Speech may resemble the

abbreviated language used in text messages. The difficulty and delay in word-finding

lead to frustration in the patient. Not infrequently there is an associated dysarthria and motor disturbance affecting face and tongue

Fig. 14.2 The two broad groups of dysphasia.

The patient is not able to understand spoken words normally. Other people's speech is heard and transmitted to the brain normally, but conversion to ideas in the patient's brain is impaired. His ability to monitor his own speech, to make sure that the correct words are used to express his own ideas, is impaired. Speech is excessive, void of meaning, words are substituted (paraphasias) and new words used (neologisms). The patient does not understand what is said to him, and has difficulty in obeying instructions. The patient may appear so out of contact to be regarded as psychotic. Awareness of his speech problem and frustration are not very evident

1 |

Weakness of the right face, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

hand and arm |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

Sensory impairment in the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

right face, hand and arm |

|

1 |

2 |

|

|

||

3 |

Difficulties with: |

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

written words . . . dyslexia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and dysgraphia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

numbers . . . dyscalculia |

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

visual field . . . right |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

homonymous hemianopia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

Impairment of memory, |

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

alteration of behaviour |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 14.3 The common associated neurological abnormalities in dysphasic patients.

228

Features of dementia

The commonly encountered defects in intellectual function that occur in patients with dementia, together with the effects that such defects have, are shown below. Because the dementing process usually develops slowly, the features of dementia evolve insidiously, and are often ‘absorbed’ by the patient’s family. This is why dementia is often advanced at the time of presentation.

CHAPTER 14

. . . a forgetful person, in no real distress, who can no longer do their job, can no longer be independent, and who cannot really sustain any ordinary sensible conversation

|

|

|

|

|

Defect in: |

Effects |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Memory |

• Disorientation, especially in time |

|

|

|

• Impaired knowledge of recent events |

|

|

|

• Forgets messages, repeats himself, loses things about the house |

|

|

|

• Increasing dependence on familiar surroundings and daily routine |

|

|

Thinking, understanding, |

• Poor organization |

|

|

reasoning and initiating |

• Ordinary jobs muddled and poorly executed |

|

|

|

• Slow, inaccurate, circumstantial conversation |

|

|

|

• Poor comprehension of argument, conversation and TV programmes |

|

|

|

• Difficulty in making decisions and judgements |

|

|

|

• Fewer new ideas, less initiative |

|

|

|

• Increasing dependence on relatives |

|

|

Dominant hemisphere |

• Reduced vocabulary, overuse of simple phrases |

|

|

function |

• Difficulty in naming things and word-finding |

|

|

|

• Occasional misuse of words |

|

|

|

• Reading, writing and spelling problems |

|

|

|

• Difficulties in calculation, inability to handle money |

|

|

Non-dominant hemisphere |

• Easily lost, wandering and difficulty dressing (spatial disorientation) |

|

|

function |

|

|

|

Insight and emotion |

• Usually lacking in insight, facile |

|

|

|

• Occasionally insight is intact, causing anxiety and depression |

|

|

|

• Emotional lability may be present |

|

|

|

• Socially or sexually inappropriate behaviour |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DEMENTIA |

229 |

Testing intellectual function (with some reference to

anatomical localization)

Talking to the patient, in an attempt to obtain details of the history, will have indicated the presence of impairment of intellectual function in most instances. The next tasks are to find out how severely affected intellectual function is, and whether all aspects of the intellect are involved, i.e. global dementia, or whether the problem is localized.

Dysphasia |

Bilateral frontal and temporal regions |

Establish first whether there is significant expressive |

• Look for and ask about behavioural changes of |

or receptive dysphasia, because these make it hard |

frontotemporal disorder: |

to use most of the other bedside tests of intellectual |

• self-neglect, apathy and social withdrawal |

function. The features of dysphasia are described in |

• socially or sexually inappropriate behaviour |

Fig. 14.2 |

• excessive and uncharacteristic consumption |

• Listen for expressive dysphasia: hesitant speech, |

of alcohol or sweet foods |

struggling to find the correct word and using |

• lack of insight into these changes |

laborious ways round missing words (circumlocution) |

• Test orientation in time and place, and recall of |

• Test for receptive dysphasia by asking the patient |

current affairs (if the patient does not follow the |

to follow increasingly complex commands, e.g. 'close |

news, try sport or their favourite soap opera) |

your eyes,' 'put one hand on your chest and the other |

• Test attention and recall, asking the patient to |

on your head,' 'touch your nose, put on your |

repeat a name and address immediately and after |

spectacles, and stand up' |

5 minutes |

• In both situations the patient may use the wrong |

• Test frontal lobe function. Ask the patient to give |

words |

the meaning of proverbs (looking for literal or |

|

'concrete' interpretations rather than the abstract |

|

meaning), or to generate a list of words beginning |

|

with a particular letter (usually very slow and |

|

repetitive) |

|

|

C |

|

B |

|

A |

|

Dominant hemisphere |

Non-dominant hemisphere |

Spoken language (A) |

• Test for contralateral limb sensory inattention or |

• Test vocabulary, naming of objects, misuse of words |

visual field inattention |

and ability to follow multicomponent commands |

• Ask about loss of spatial awareness, where the |

|

patient becomes lost in familiar surroundings, or |

Written language (B) |

struggles with the correct arrangement of clothes |

• Test reading, writing and calculation |

on his body (dressing dyspraxia) |

|

• Test ability to draw a clock and copy a diagram of |

Parietal dysfunction (C) |

intersecting pentagons |

• Test for contralateral limb sensory inattention or |

|

visual field inattention |

|

|

|