- •Предисловие

- •Содержание:

- •The United States of America

- •One nation, under God, with Liberty and Justice for all.

- •The United States

- •Us State Nicknames

- •Illinois

- •Indiana (no official nickname)

- •Vermont

- •Virginia

- •Some of the benchmark events of American history mentioned in the “Gallery of American Presidents”:

- •Монеты сша

- •White House History

- •About the Building

- •The Oval Office

- •Eisenhower Executive Office Building

- •Camp David

- •Air Force One

- •Us Government The Executive Branch

- •The President

- •The Vice President

- •Executive Office of the President

- •The Cabinet

- •Department of Agriculture

- •Department of Commerce

- •Department of Defense

- •Department of Education

- •Department of Energy

- •Department of Health and Human Services

- •Department of Homeland Security

- •Department of Housing and Urban Development

- •Department of the Interior

- •Department of Justice

- •Department of Labor

- •Department of State

- •Department of Transportation

- •Department of the Treasury

- •Department of Veterans Affairs

- •The Legislative Branch

- •The Legislative Process

- •Powers of Congress

- •Government Oversight

- •The Judicial Branch

- •The Supreme Court of the United States

- •The Judicial Process

- •The Constitution

- •Why a Constitution?

- •The Constitutional Convention

- •Ratification

- •The Bill of Rights

- •Elections & Voting

- •The great seal of the united states

- •Designing a Seal The First Committee

- •The Second Committee

- •The Third Committee

- •Charles Thomson’s Proposal

- •The Final “Device”

- •Charles Thomson’s “Remarks and Explanation,” Adopted by the Continental Congress, June 20, 1782

- •Its simplicity and lack of clutter. His design was

- •Meaning of the Seal

- •Designs of the Reverse

- •In 1782, no die has ever

- •Uses of the Seal and the Coat of Arms

- •Requests To Use the Great Seal and Coat of Arms

- •Great Seal Today

- •The Great Seal of the United States

- •The Great Seal on Display

- •Langley

- •Central intelligence agency

- •The work of a nation. The centre of intelligence. About cia

- •Today's cia

- •Mission

- •The cia Campus: a Walk Outside Headquarters

- •Nathan Hale Statue

- •Memorial Garden

- •The cia Campus: New Headquarters Building

- •The History of the Scattergood-Thorne Property

- •Cia Glossary

- •Laughing at cia?

- •The lapd, the fbi and the cia

- •Federal Bureau of Investigation

- •Laughing at fbi?

- •An fbi investigation

- •9/11 Warnings and fbi/cia Bungling

- •Late-Night Jokes About Sept. 11 Intelligence Failures

- •Foggy Bottom

- •Hitting Bottom in Foggy Bottom The State Department suffers from low morale, bottlenecks, and bureaucratic ineptitude. Do we need to kill it to save it? by matthew armstrong | september 11, 2009

- •The Watergate hotel

- •Us Department of State Headquarters

- •History

- •Duties and responsibilities

- •American entertainment

- •Hollywood

- •Hollywood glossary

- •Capitol Records

- •.. 1750 Vine Street, Hollywood, ca. / (323) 462-6252

- •On Hollywood Boulevard: from Gower Street to La Brea Avenue, and on Vine Street: from Yucca Street to Sunset Boulevard.

- •Hollywood glossary

- •"Celebrity Death Sites" a list of celebrities, whose deaths were the result of murder or suicide, including the location of their death sites

- •John Belushi's Death Site"

- •John Belushi's Death Site.

- •Silicon Valley

- •Вот, что мне особенно понравилось (для людей, изучающих английский, может показаться странным, что некоторые слова попали в разряд «чудных» с точки зрения американца).

- •Distinctive features Phonology

- •Grammatical aspect marking

- •Ebonics Translations

- •Ebonics Prayer

- •Nursery Rhymez

- •The us army

- •Army Commands (acom):

- •Army Service Component Commands (ascc):

- •Direct Reporting Units (dru):

- •Mission

- •“The Army Goes Rolling Along”

- •Пример описания боевых характеристик: Patriot

- •Entered Army Service

- •Description and Specifications

- •Manufacturer

- •Униформа армии сша

- •Знаки различия званий уорент-офицеров (Warrant Officers).

- •Знаки различия званий младших офицеров (Сompany Grade Officers).

- •Знаки различия званий старших офицеров (Field Grade Officers).

- •Знаки различия званий генералов (General Officers).

- •Наградная система армии сша

- •2. Крест за выдающуюся службу (Distinguished Service Cross).

- •8. Медаль Министерства обороны за отличную службу (Defense Superior Service Medal).

- •9. «За боевые заслуги», Орден Почетного Легиона (Legion of Merit).

- •Military Humour

- •Спецназ сша/us special forces

- •Рейнджеры / us Army Rangers

- •Спецподразделения Военно-воздушных сил сша / us Air Force Special Operations

- •Спецподразделения военно-морского флота сша, известны как "морские котики"/us Navy Seals

- •Отряд "Дельта" / Delta Force

- •Разведка Морской Пехоты сша / us Marine Force Recon

- •Воздушно-десантные войска/ us Airborn

- •Десятая Горная Дивизия/10th Mountain Division

- •Полувоенные силы Центрального Разведывательного Управления/cia Paramilitary Forces

- •Начало формы Конец формы

- •Sightseeing in america

- •Visual Landmarks New York

- •Районы Нью-Йорка

- •Управление

- •Культура

- •Планировка города

- •Транспорт

- •Сигналы опасности

- •Мосты и туннели

- •Связь в Нью-Йорке

- •Что раздражает ньюйоркцев?

- •Manhattan

- •Башня Банка Америки (Bank of America Tower)

- •Эмпайр Стейт Билдинг Why do we call New York City the Big Apple?

- •Statue of Liberty

- •The National Park Service commemorates the anniversary of the Statue of Liberty annually on October 28th. Mount rushmore

- •The grand canyon

- •Niagara Falls

- •Alcatraz

- •History

- •Military history

- •Military prison

- •Prison history Federal prison

- •Notable inmates

- •Post prison years

- •Native American occupation

- •Landmarking and development

- •Arlington National Cemetery

- •Placing of burial flag over a casket

- •A firing party

- •Сто вопросов и ответов о сша one hundred questions and answers about

- •2. What are the ingredients of a traditional American Thanksgiving dinner?

- •3. What do the terms "melting pot" and "salad bowl" mean to u.S. Society and culture?

- •Impressionists?

- •67. Which American President was the first to live in the White House?

- •Isbn 987–5–932050–42–2

- •191104, Г. Санкт-Петербург, наб. Р. Фонтанки, 32/1

Some of the benchmark events of American history mentioned in the “Gallery of American Presidents”:

The Louisiana Purchase |

The Louisiana Purchase (French: Vente de la Louisiane "Sale of Louisiana") was the acquisition by the United States of America of 828,800 square miles (2,147,000 km2) of the French territory Louisiana in 1803. The U.S. paid 60 million francs ($11,250,000) plus cancellation of debts worth 18 million francs ($3,750,000), a total cost of 15 million dollars for the Louisiana territory. |

The Lewis and Clark Expedition |

The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806) was the first overland expedition undertaken by the United States to the Pacific coast and back. The expedition team was headed by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and assisted by Sacajawea and Toussaint Charbonneau. The expedition's goal was to gain an accurate sense of the resources being exchanged in the Louisiana Purchase. The expedition laid much of the groundwork for the westward expansion of the United States. |

25th amendment |

Section 1. In case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation, the Vice President shall become President. Section 2. Whenever there is a vacancy in the office of the Vice President, the President shall nominate a Vice President who shall take office upon confirmation by a majority vote of both Houses of Congress. Section 3. Whenever the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, and until he transmits to them a written declaration to the contrary, such powers and duties shall be discharged by the Vice President as Acting President. Section 4. Whenever the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall immediately assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President. Thereafter, when the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that no inability exists, he shall resume the powers and duties of his office unless the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive department or of such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmit within four days to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives their written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office. Thereupon Congress shall decide the issue, assembling within forty-eight hours for that purpose if not in session. If the Congress, within twenty-one days after receipt of the latter written declaration, or, if Congress is not in session, within twenty-one days after Congress is required to assemble, determines by two-thirds vote of both Houses that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice President shall continue to discharge the same as Acting President; otherwise, the President shall resume the powers and duties of his office. |

The Missouri Compromise

|

In February 1819, New York Representative James Tallmadge proposed an amendment to ban slavery in Missouri even though there were more than 2,000 slaves living there. The country was again confronted with the volatile issue of the spread of slavery into new territories and states. The cry against the South's "peculiar institution" had grown louder through the years. "How long will the desire for wealth render us blind to the sin of holding both the bodies and souls of our fellow men in chains?" Asked Representative Livermore from New Hampshire. The South's economy was dependent upon black slavery, and 200 years of living with the institution had made it an integral part of Southern life and culture. The South demanded that the North recognize its right to have slaves as secured in the Constitution. Through the efforts of Henry Clay, "the great pacificator," a compromise was finally reached on March 3, 1820, after Maine petitioned Congress for statehood. Both states were admitted, a free Maine and a slave Missouri, and the balance of power in Congress was maintained as before, postponing the inevitable showdown for another generation. In an attempt to address the issue of the further spread of slavery, however, the Missouri Compromise stipulated that all the Louisiana Purchase territory north of the southern boundary of Missouri, except Missouri, would be free, and the territory below that line would be slave. Fascinating Fact: The Missouri Compromise was repealed by the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act and declared unconstitutional in the 1857 Dred Scott decision. |

The Monroe Doctrine

|

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States policy that was introduced on December 3, 1823, which said that further efforts by European governments to colonize land or interfere with states in the Americas would be viewed by the United States of America as acts of aggression requiring US intervention. The Monroe Doctrine asserted that the Western Hemisphere was not to be further colonized by European countries, and that the United States would not interfere with existing European colonies nor in the internal concerns of European countries. The Doctrine was issued at the time when many Latin American countries were on the verge of becoming independent from Spain, and the United States, reflecting concerns echoed by Great Britain, hoped to avoid having any European power take Spain's colonies. US President James Monroe first stated the doctrine during his seventh annual State of the Union Address to Congress. It became a defining moment in the foreign policy of the United States and one of its longest-standing tenets, invoked by U.S. presidents Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, John F. Kennedy, and others. |

Panic of 1837

|

The early 1830s was a time of expansion and prosperity. Much of the growth in these years had been fueled by the widespread construction of new railroads and canals. Millions of acres of public lands were sold by the government, mostly to speculators. These government land sales, coupled with the Tariff of 1833, brought huge amounts of money into the Treasury’s coffers. In 1835, the government was able to pay off the national debt—one of the fondest dreams of President Andrew Jackson. For one of the few times in American history, the Treasury rapidly began to accumulate a surplus. Members of Congress responded to pressures from home and passed a measure distributing the surplus to the states. The windfall was quickly invested in further internal improvement projects-more railroads and canals. Most state governments, as well as many individuals, preferred to hoard specie (gold and silver) and to discharge debts with paper bank notes. Jackson became alarmed by the growing influx of state bank notes being used to pay for public land purchases and, in 1836 shortly before leaving office, issued the Specie Circular. This order commanded the Treasury to no longer accept paper notes as payment for such sales. Westerners were dismayed by this action, and a major bank crisis awaited the incoming administration of Martin Van Buren, in early 1837. Banks restricted credit and called in loans. Depositors rushed to their local institutions and attempted to withdraw their funds. Unemployment soon touched every part of the nation and food riots occurred in a number of large cities. Construction companies were unable to meet their obligations, sparking the failure of railroad and canal projects, and the ruin of thousands of land speculators. The impact of the depression lingered until 1843. |

The Whigs

|

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from 1833 to 1856, the party was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and the Democratic Party. In particular, the Whigs supported the supremacy of Congress over the executive branch and favored a program of modernization and economic protectionism. This name was chosen to echo the American Whigs of 1776, who fought for independence, and because "Whig" was then a widely recognized label of choice for people who saw themselves as opposing autocratic rule. The Whig Party counted among its members such national political luminaries as Daniel Webster, William Henry Harrison, and their preeminent leader, Henry Clay of Kentucky. In addition to Harrison, the Whig Party also counted four war heroes among its ranks, including Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott. Abraham Lincoln was a Whig leader in frontier Illinois. The party was ultimately destroyed by the question of whether to allow the expansion of slavery to the territories. With deep fissures in the party on this question, the anti-slavery faction successfully prevented the nomination of its own incumbent President Fillmore in the 1852 presidential election; instead, the party nominated General Winfield Scott, who was soundly defeated. Its leaders quit politics (as Lincoln did temporarily) or changed parties. The voter base defected to the Republican Party, various coalition parties in some states, and to the Democratic Party. By the 1856 presidential election, the party had lost its ability to maintain a national coalition of effective state parties and endorsed Millard Fillmore, now of the American Party, at its last national convention. |

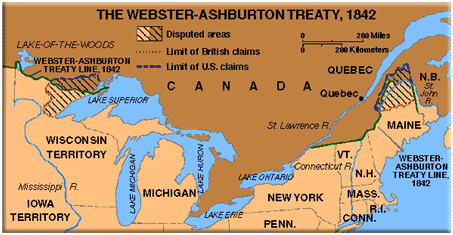

The Webster-Ashburton treaty

|

In 1842, Secretary of State Daniel Webster met with the British Foreign Minister, Alexander Baring, the first Baron Ashburton. The resulting Webster-Ashburton Treaty reached agreement on the following points:

One question of growing concern, the Oregon boundary issue, was not addressed in this agreement.

The Webster-Ashburton Treaty was significant in that it furthered the practice of settling troublesome issues through diplomacy. |

Manifest Destiny

|

This painting (circa 1872) by John Gast called American Progress is an allegorical representation of Manifest Destiny. In the scene, an angelic woman (sometimes identified as Columbia, a nineteenth-century personification of the United States) carries the light of "civilization" westward with American settlers, stringing telegraph wire as she travels. American Indians, buffalos and wild animals are driven into the darkness before them. Manifest Destiny is a nineteenth-century belief that the United States had a mission to expand westward across the North American continent, spreading its form of democracy, freedom, and culture. The expansion was deemed to be not only good, but also obvious ("manifest") and certain ("destiny"). Many believed the mission to be divinely inspired while others felt it more as an altruistic right to expand the territory of liberty. Originally a political catch phrase of the nineteenth century, Manifest Destiny eventually became a standard historical term, often used as a synonym for the territorial expansion of the United States across North America. The phrase was first used primarily by Jackson Democrats in the 1840s to promote the annexation of much of what is now the Western United States (the Oregon Territory, the Texas Annexation, and the Mexican Cession). The term was revived in the 1890s, this time with Republican supporters, as a theoretical justification for U.S. intervention outside of North America. The term fell out of common usage by American politicians, but some commentators believe that aspects of Manifest Destiny continued to have an influence on American political ideology in the twentieth century. |

Compromise of 1850

|

The Compromise of 1850 consists of five laws passed in September of 1850 that dealt with the issue of slavery. In 1849 California requested permission to enter the Union as a free state, potentially upsetting the balance between the free and slave states in the U.S. Senate. Senator Henry Clay introduced a series of resolutions on January 29, 1850, in an attempt to seek a compromise and avert a crisis between North and South. As part of the Compromise of 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was amended and the slave trade in Washington, D.C., was abolished. Furthermore, California entered the Union as a free state and a territorial government was created in Utah. Also, an act was passed settling a boundary dispute between Texas and New Mexico that also established a territorial government in New Mexico. |

Emancipation Proclamation

|

By the President of the United States of America: A Proclamation. "That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom. "That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith, represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States." ……………. “And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons. And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages. And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service. And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God. In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed. Done at the City of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh. ABRAHAM LINCOLN L.S. By the President: WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.

|

Appomattox |

Peace and Reunification With his army surrounded, his men weak and exhausted, Robert E. Lee realized there was little choice but to consider the surrender of his Army to General Grant. After a series of notes between the two leaders, they agreed to meet on April 9, 1865, at the house of Wilmer McLean in the village of Appomattox Courthouse. The meeting lasted approximately two and one-half hours and at its conclusion the bloodiest conflict in the nation's history neared its end. On Palm Sunday, 1865, Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House, Virginia signaled the end of the Southern States attempt to create a separate nation. It set the stage for the emergence of an expanded and more powerful Federal government. In a sense the struggle over how much power the central government would hold had finally been settled.

|

Sherman Antitrust Act

|

This ground breaking piece of legislation was the result of intense public opposition to the concentration of economic power in large corporations and in combinations of business concerns (i,e., trusts) that had been taking place in the U.S. in the decades following the Civil War. Opposition to the trusts was particularly strong among farmers, who protested the high charges for transporting their products to the cities by railroad. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was the first measure enacted by the U.S. Congress to prohibit trusts (or monopolies of any type). Although several states had previously enacted similar laws, they were limited to intrastate commerce. The Sherman Antitrust Act, in contrast, was based on the constitutional power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce. It was passed by an overwhelming vote of 51 to 1 in the Senate and a unanimous vote of 242 to 0 in the House, and it was signed into law by President Benjamin Harrison.

|

Warren Commission

|

PRESIDENT LYNDON B. JOHNSON, by Executive Order No. 11130 dated November 29, 1963, created this Commission to investigate the assassination on November 22, 1963, of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the 35th President of the United States. The President directed the Commission to evaluate all the facts and circumstances surrounding the assassination and the subsequent killing of the alleged assassin and to report its findings and conclusions to him. Warren Commission was called after its chairman Chief Justice Earl Warren. The Commission issued its now-famous finding that Lee Harvey Oswald, alone and unaided, killed President Kennedy in Dallas on November 22, 1963. It further found that Jack Ruby's murder of Oswald, while Oswald was in police custody, was also not part of any conspiracy. In addition to the published 26 volumes of evidence, the released files of the Warren Commission include over 50,000 pages of numbered documents, internal memorandum, transcripts of Executive Sessions, and more. The testimony and files of the Commission serve as an important base of evidence in any understanding of the events in Dallas. |

Watergate scandal

|

In June of 1972 in Washington, D.C. an event occurred, a burglary, which ended up holding worldwide importance. It was on this date that five people broke into the Democratic National Headquarters to bug their telephones. These men were members of the ‘Plumbers’, a group of anti-Castro Cuban refugees, former FBI agents and former CIA agents among others. The group was strongly Republican. The place they broke into was The Watergate Hotel. Many people remember the name Watergate as a blanket term used to describe the fall of President Richard Nixon. The Plumbers were a ‘secret’ unit created and maintained by the White House with the expressed purpose of ‘fixing leaks’ in the administration. They worked tirelessly at their goal and were soon rewarded with another job in the following election year: derailing the Democratic ticket. On June 17, 1972 a group of men broke into the DNC Headquarters to find what they could and to bug the offices. A sharp-eyed security officer saw the break in, called the police and the burglars were quickly taken into custody. Over the next few days and months, amazing insights into these men came out. One of the burglars used to be a GOP security aide, another was found to have a 25,000$ check that was supposed to have gone to Nixon’s re-election campaign. In fact, it turned out that all of the burglars were on the payroll of the Committee to Re-Elect the President (C.R.E.E.P.). As this unfolded, Nixon went on to win the presidential election in one of the biggest landslides in history. It would be Nixon’s last big win. Following his re-election the repercussions from the Watergate break-in grew larger. Several of the burglars went to jail. As the connection between these burglars and the Republican White House grew stronger, several White House staffers were forced to resign and White House Chief Counsel John Dean resigned. Nowadays "Watergate" is a general term used to describe a complex web of political scandals between 1972 and 1974. The burglary and subsequent cover-up eventually led to moves to impeach President Richard Nixon. Nixon resigned the presidency on 8 August 1974. "Watergate" is now an all-encompassing term used to refer to:

Most of all, "Watergate" is synonymous with abuse of power. |

Camp David Accords

|

September 17, 1978 After twelve days of secret negotiations at Camp David, the Israeli-Egyptian negotiations were concluded by the signing at the White House of two agreements. The first dealt with the future of the Sinai and peace between Israel and Egypt, to be concluded within three months. The second was a framework agreement establishing a format for the conduct of negotiations for the establishment of an autonomy regime in the West Bank and Gaza. The Israel-Egypt agreement clearly defined the future relations between the two countries, all aspects of withdrawal from the Sinai, military arrangements in the peninsula such as demilitarization and limitations, as well as the supervision mechanism. The framework agreement regarding the future of Judea, Samaria and Gaza was less clear and was later interpreted differently by Israel, Egypt, and the US. President Carter witnessed the accords which were signed by Egyptian President Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Begin. |

Fair Housing Act

|

The Fair Housing Act, 42 U.S.C. 3601 et seq., prohibits discrimination by direct providers of housing, such as landlords and real estate companies as well as other entities, such as municipalities, banks or other lending institutions and homeowners insurance companies whose discriminatory practices make housing unavailable to persons because of:

In cases involving discrimination in mortgage loans or home improvement loans, the Department may file suit under both the Fair Housing Act and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act. Under the Fair Housing Act, the Department of Justice may bring lawsuits where there is reason to believe that a person or entity is engaged in a "pattern or practice" of discrimination or where a denial of rights to a group of persons raises an issue of general public importance. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

FIRST LADIES |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|