- •A Country Across the Channel

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •V. Draw a sketch-map of the British Isles and mark in the following.

- •Britain-an Island, or a Peninsula?

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •V. Do you remember?

- •The Face of Britain

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •V. Draw a sketch map of the British Isles and include

- •Climate and Weather

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Mineral Wealth

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Who Are the British? (I) Ancient and Roman Britain

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Who Are the British ? (II) t he Anglo-Saxons, Danes and Normans

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Who Are the British? (Ill) The Irish

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Stonehenge and Avebury

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •V. Explain the following

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •V. Do you remember?

- •Northern Ireland - the Land of the Giant's Causeway

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the Questions.

- •V. Explain:

- •Great Britain - a Constitutional Monarchy

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, bore).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Mother of Parliaments

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •The Party System and the Government

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •The Press

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Radio and Television

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •The School Education

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •The Public Schools

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •The Economy. The South

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •The Regions of Britain

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •V. Do you remember?

- •Transport

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Agriculture

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Food and Meals

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Some National Traits

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •The Church In Modern Life

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •The British In Their Private Life

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •V. Do you remember?

- •English Gardens and Gardeners

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Leisure and Sports

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •King Arthur

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •V. Do you remember?

- •"My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean... "

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Canterbury Cathedral and Geoffrey Chaucer - the Great English Story-Teller

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Shakespeare and Shakespeareland

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Britain's Great Hero

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •"The Lady With the Lamp"

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, b or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Museums and Other Treasures

- •I. Fill in the blanks with the correct words.

- •II. Complete the sentences with the best answer (a, h or c).

- •III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

- •IV. Answer the questions.

- •Chronological outline

- •Kings and queens of england from alfred

- •British prime ministers and governments

III. Are the statements true or false? Correct the false statements.

1. Before the 17th century there was little need for rapid communication, because most local areas were relatively self-sufficient in raw materials for industry.

2. The impetus for the development of railway communications came from the expanding oil trade of the early 19th century.

3. During the 19th century and the early years of the 20th century the railways were the principal carriers of both freight and passengers.

4. For example, during the boom years rival companies built many competing parallel lines between the major cities and, as traffic declined, some of these lines became seriously overloaded.

5. Modern methods of evaluating road requirements for the future have been developed by government planners and a system of motorways linking many parts of Britain was begun in the late 1950s.

6. Most of Britain's roads were designed to handle horse-drawn traffic and are adequate for modern motor vehicles, especially modern lorries.

7. Overseas communications are inseparable from Britain's trade which is handled at a number of ports.

8. Specialized naval ports include Brighton and Hastings.

9. The number of people who travel by air has increased at a very fast rate.

IV. Answer the questions.

1. Comment on the movement of agricultural and industrial products on the one hand, and raw materials and labour on the other.

2. Why was there little need for rapid communication before the 17th century?

3. What caused building more suitable means of transport than had existed previously?

4. Examine the role and importance of water transport in the Middle Ages.

5. Where did the impetus for the development of railway communications come from?

6. What caused a decline in the importance of the railways and the closure of many lines and stations?

7. Describe the pattern of roads in Britain and the role of the motor vehicle transport.

8. What problems are created by the increased motor traffic?

9. Why are overseas communications inseparable from Britain's trade?

10. Give an outline of the growth of air traffic and Britain's chief airport Heathrow.

Points for discussion

1. The role of transport in different periods of history.

2. The development of road and railway network in Britain.

3. Transport in the life of the people today.

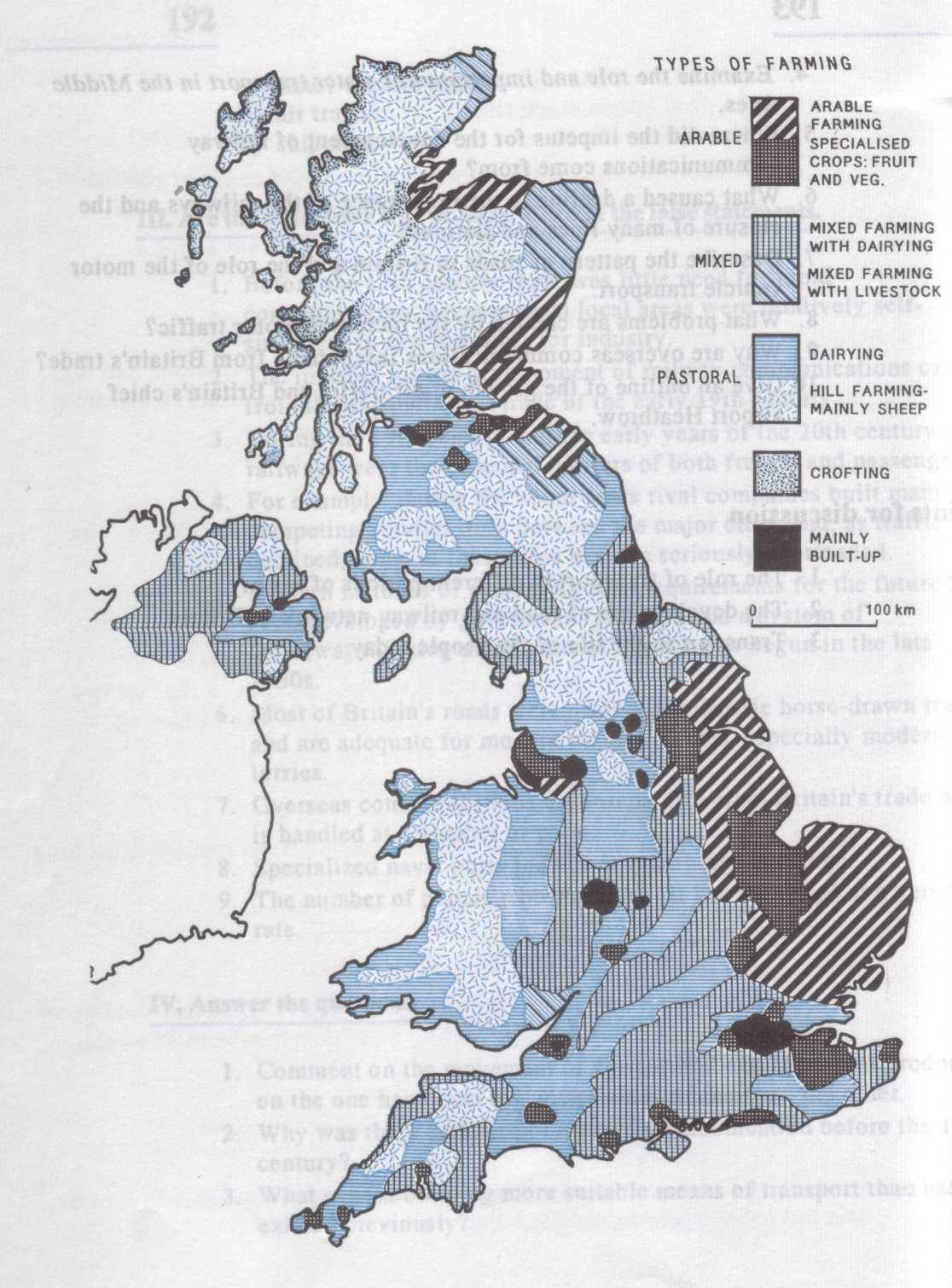

Agriculture

B efore

the Industrial Revolution, Britain had a comparatively small

population. She did not experience any difficulty in providing all

the grain and meat required for home consumption. But during the

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as the Industrial Revolution

gathered speed, not only did the number of people increase rapidly,

but also many of those who had previously been employed on the land

went to work in the factories and mines. Britain became an industrial

and trading nation which ceased to be self-supporting in foodstuffs.

It was necessary that the most efficient use should be made of the

country's limited agricultural resources. And important changes took

place which have given British farming its present character.

efore

the Industrial Revolution, Britain had a comparatively small

population. She did not experience any difficulty in providing all

the grain and meat required for home consumption. But during the

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as the Industrial Revolution

gathered speed, not only did the number of people increase rapidly,

but also many of those who had previously been employed on the land

went to work in the factories and mines. Britain became an industrial

and trading nation which ceased to be self-supporting in foodstuffs.

It was necessary that the most efficient use should be made of the

country's limited agricultural resources. And important changes took

place which have given British farming its present character.

A wide range of measures was introduced to increase agricultural efficiency. The careful crossing of existing breeds of cattle and sheep produced types of animals which gave increased yields of meat and milk. Artificial fertilizers came to be manufactured. A so-called rotation system was invented, in which the fertility of the land is maintained by growing different crops. And, of course, the introduction of up-to-date machinery was a decisive factor.

Although the vast majority of the population lives and works in towns, urban areas occupy a small proportion of the total land area of Britain. Over three-quarters of the land area is used for agriculture, the remainder being mountain, forest or put to urban and other uses. Britain's agriculture is famous for its high level of efficiency and productivity. In spite of the fact that the agricultural area of the country is fairly large, only about 2.5 per cent of the working population are engaged in agriculture. It produces nearly two-thirds of Britain's food requirements compared with just a half in 1960.

Land which is normally used for the cultivation of crops accounts for about 20 per cent of the land surface, rather less than the amount occupied by permanent grassland. Although cultivable land is found in almost every lowland, particular concentrations of such land occur in eastern England and eastern Scotland, where precipitation is less than 760 mm per year.

The present pattern of farming in Britain owes much to decisions taken by the Government. During the nineteenth century, Britain became increasingly dependent on imported food. The danger of this situation became particularly evident during the two world wars when the country realized what situation was like as a result of the German blockade. As a consequence it was decided to support agriculture by paying subsidies to farmers which would help them to compete with foreign producers. This meant that food could be sold in shops at prices which did not cover production costs and that the British farmer depended for his profit upon subsidies from the Government. So, British agriculture is protected by an artificial price structure and by taxes imposed on imported food.

Modern British farming displays two important characteristics. In the first place, it is intensive farming, in other words, no effort is spared to achieve maximum production from the available land. The output of crops per hectare and the quality of the livestock are very high. In the second place, it is mixed farming, in which both crops and livestock play an important part. Only in special areas, such as those devoted to market-gardening or fruit-growing, are activities concentrated upon one particular type of occupation.

The most widespread arable crops grown in Britain together with other minor cereals and root crops are wheat, barley and oats. Climate is the chief factor limiting the successful cultivation of cereal crops, especially of wheat. Therefore the farms devoted mostly to arable crops are found mainly in eastern and southern England and eastern Scotland.

Almost all Britain's WHEAT crop is "winter wheat" which is sown in the autumn. Because of the dampness of the climate it is of the type known as "soft" wheat, in contrast to the "hard" wheat produced in other countries, as the USA or Canada.-Since bread made only from soft wheat is of lower quality and slightly grey in colour it is customary to use flour of which about 70 per cent has been made from "hard" imported wheat. Soft wheat, however, is excellent for making biscuits. About one-third of the wheat crop is normally used for flour milling, and about one-third for animal feed.

BARLEY grows best under the same conditions as wheat. It is much more adaptable as far as soil, temperature and rainfall are concerned, and requires a shorter ripening period. That is why areas devoted to barley and wheat roughly coincide, but barley is also grown in cooler, more northerly districts of eastern Scotland and in moister regions in Ireland.

Barley is used principally for fodder (40 per cent). But a certain kind of barley with a low nitrogen content is particularly suitable for the production of beer and whisky (15 percent).

In recent years exports of wheat and barley have increased considerably, accounting for about a quarter of the total production.

Although OATS are more tolerant of poor soils and cool damp conditions the area under this crop is gradually decreasing. This is largely because it is being required less and less to feed horses as mechanisation takes over on the farms. Oats tend to be used in the areas in which they are grown. In England, Wales and Ireland their chief use is as winter feed for cattle. Scotland is one of the few countries in which oats are cultivated for human consumption, to make porridge, oatcakes, etc.

Of root crops cultivated in Britain, most important are potatoes and sugar beet. POTATOES are cultivated throughout the British Isles, but the main areas of production are Cambridgeshire and Lincolnshire in eastern England and in the eastern part of central Scotland. South-west Wales, Kent and south-west England, having a mild winter, are notable for early potatoes. High-grade seed potatoes are grown in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

SUGAR BEET is a root crop which in recent years has assumed considerable importance. Today it provides about 50 per cent of sugar requirements of the country. The best place for growing sugar beet is eastern England, and here for convenience, since it is a bulky crop to transport, most of the sugar-making factories are situated.

MARKET GARDENING may be defined as the intensive production of vegetables and fruit for human consumption. Market gardens specialise in their production. As the name implies, market gardening is strongly influenced by access to markets. This is largely because both fruit and vegetables deteriorate rapidly after packing and must, therefore, be moved to market as quickly as possible. As a result, market gardens have been growing up near to large industrial cities, supplying such industrial areas as Midland England, Lancashire and Yorkshire. Orchards in which fruit-growing is organised on a commercial scale are found principally in the southern half of England, where the climate is most favourable.

Glasshouses are widely used for growing tomatoes, cucumbers, lettuce, flowers, pot plants and nursery stock.

The climate of the British Isles is ideal for CATTLE. Therefore, they are found practically in all areas, particularly in the Midlands and south-west of England, the lowlands of Yorkshire and the coastal areas of Scotland, Wales, the Lake District and Northern Ireland. In contrast, sheep are concentrated in the upland areas of Scotland, Wales, northern and southwestern England and Northern Ireland.

Since British agriculture is highly specialised, cattle serve different purposes in different districts. There are two kinds of cattle: dairy cattle and beef cattle. The need for daily deliveries of fresh milk has given rise to particular concentration of dairy cattle on lowlands close to densely populated areas. Beef cattle are more widely distributed throughout the British Isles than dairy cattle, and rearing extends into upland regions far from urban areas.

SHEEP no longer play such an important part in British agriculture as they did in the past, when there was a steady export of wool to the continent of Europe. Nowadays they are in general numerous only on land which is unsuitable for other types of farming. Although lamb production is the main source of income for sheep farmers, wool is also important.

Most farmers keep PIGS and POULTRY. Pig production occurs in most areas but is particularly important in northern and eastern England. There exists a high degree of specialisation. Poultry farms are chiefly concerned with the supply of eggs to local markets and the production of poultry meat. Britain remains self-sufficient in both.

Nowadays the area available for farming is being gradually reduced to meet the needs of housing and industry. However, the loss is outweighed by the increase in output from what remains due to the introduction of up-to-date technology and fertilizers.

Comprehension Check