- •Preface

- •List of contributers

- •History, epidemiology, prevention and education

- •A history of burn care

- •“Black sheep in surgical wards”

- •Toxaemia, plasmarrhea, or infection?

- •The Guinea Pig Club

- •Burns and sulfa drugs at Pearl Harbor

- •Burn center concept

- •Shock and resuscitation

- •Wound care and infection

- •Burn surgery

- •Inhalation injury and pulmonary care

- •Nutrition and the “Universal Trauma Model”

- •Rehabilitation

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Epidemiology and prevention of burns throughout the world

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology

- •The inequitable distribution of burns

- •Cost by age

- •Cost by mechanism

- •Limitations of data

- •Risk factors

- •Socioeconomic factors

- •Race and ethnicity

- •Age-related factors: children

- •Age-related factors: the elderly

- •Regional factors

- •Gender-related factors

- •Intent

- •Comorbidity

- •Agents

- •Non-electric domestic appliances

- •War, mass casualties, and terrorism

- •Interventions

- •Smoke detectors

- •Residential sprinklers

- •Hot water temperature regulation

- •Lamps and stoves

- •Fireworks legislation

- •Fire-safe cigarettes

- •Children’s sleepwear

- •Acid assaults

- •Burn care systems

- •Role of the World Health Organization

- •Conclusions and recommendations

- •Surveillance

- •Smoke alarms

- •Gender inequality

- •Community surveys

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •Prevention of burn injuries

- •Introduction

- •Burns prevalence and relevance

- •Burn injury risk factors

- •WHERE?

- •Burn prevention types

- •Burn prevention: The basics to design a plan

- •Flame burns

- •Prevention of scald burns

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Burns associated with wars and disasters

- •Introduction

- •Wartime burns

- •Epidemiology of burns sustained during combat operations

- •Fluid resuscitation and initial burn care in theater

- •Evacuation of thermally-injured combat casualties

- •Care of host-nation burn patients

- •Disaster-related burns

- •Epidemiology

- •Treatment of disaster-related burns

- •The American Burn Association (ABA) disaster management plan

- •Summary

- •References

- •Education in burns

- •Introduction

- •Surgical education

- •Background

- •Simulation

- •Education in the internet era

- •Rotations as courses

- •Mentorship

- •Peer mentorship

- •Hierarchical mentorship

- •What is a mentor

- •Implementation

- •Interprofessional education

- •What is interprofessional education

- •Approaches to interprofessional education

- •References

- •European practice guidelines for burn care: Minimum level of burn care provision in Europe

- •Foreword

- •Background

- •Introduction

- •Burn injury and burn care in general

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Pre-hospital and initial management of burns

- •Introduction

- •Modern care

- •Early management

- •At the accident

- •At a local hospital – stabilization prior to transport to the Burn Center

- •Transportation

- •References

- •Medical documentation of burn injuries

- •Introduction

- •Medical documentation of burn injuries

- •Contents of an up-to-date burns registry

- •Shortcomings in existing documentation systems designs

- •Burn depth

- •Burn depth as a dynamic process

- •Non-clinical methods to classify burn depth

- •Burn extent

- •Basic principles of determining the burn extent

- •Methods to determine burn extent

- •Computer aided three-dimensional documentation systems

- •Methods used by BurnCase 3D

- •Creating a comparable international database

- •Results

- •Conclusion

- •Financing and accomplishment

- •References

- •Pathophysiology of burn injury

- •Introduction

- •Local changes

- •Burn depth

- •Burn size

- •Systemic changes

- •Hypovolemia and rapid edema formation

- •Altered cellular membranes and cellular edema

- •Mediators of burn injury

- •Hemodynamic consequences of acute burns

- •Hypermetabolic response to burn injury

- •Glucose metabolism

- •Myocardial dysfunction

- •Effects on the renal system

- •Effects on the gastrointestinal system

- •Effects on the immune system

- •Summary and conclusion

- •References

- •Anesthesia for patients with acute burn injuries

- •Introduction

- •Preoperative evaluation

- •Monitors

- •Pharmacology

- •Postoperative care

- •References

- •Diagnosis and management of inhalation injury

- •Introduction

- •Effects of inhaled gases

- •Carbon monoxide

- •Cyanide toxicity

- •Upper airway injury

- •Lower airway injury

- •Diagnosis

- •Resuscitation after inhalation injury

- •Other treatment issues

- •Prognosis

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Respiratory management

- •Airway management

- •(a) Endotracheal intubation

- •(b) Elective tracheostomy

- •Chest escharotomy

- •Conventional mechanical ventilation

- •Introduction

- •Pathophysiological principles

- •Low tidal volume and limited plateau pressure approaches

- •Permissive hypercapnia

- •The open-lung approach

- •PEEP

- •Lung recruitment maneuvers

- •Unconventional mechanical ventilation strategies

- •High-frequency percussive ventilation (HFPV)

- •High-frequency oscillatory ventilation

- •Airway pressure release ventilation (APRV)

- •Ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP)

- •(a) Prevention

- •(b) Treatment

- •References

- •Organ responses and organ support

- •Introduction

- •Burn shock and resuscitation

- •Post-burn hypermetabolism

- •Individual organ systems

- •Central nervous system

- •Peripheral nervous system

- •Pulmonary

- •Cardiovascular

- •Renal

- •Gastrointestinal tract

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Critical care of thermally injured patient

- •Introduction

- •Oxidative stress control strategies

- •Fluid and cardiovascular management beyond 24 hours

- •Other organ function/dysfunction and support

- •The nervous system

- •Respiratory system and inhalation injury

- •Renal failure and renal replacement therapy

- •Gastro-intestinal system

- •Glucose control

- •Endocrine changes

- •Stress response (Fig. 2)

- •Low T3 syndrome

- •Gonadal depression

- •Thermal regulation

- •Metabolic modulation

- •Propranolol

- •Oxandrolone

- •Recombinant human growth hormone

- •Insulin

- •Electrolyte disorders

- •Sodium

- •Chloride

- •Calcium, phosphate and magnesium

- •Calcium

- •Bone demineralization and osteoporosis

- •Micronutrients and antioxidants

- •Thrombosis prophylaxis

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Treatment of infection in burns

- •Introduction

- •Clinical management strategies

- •Pathophysiology of the burn wound

- •Burn wound infection

- •Cellulitis

- •Impetigo

- •Catheter related infections

- •Urinary tract infection

- •Tracheobronchitis

- •Pneumonia

- •Sepsis in the burn patient

- •The microbiology of burn wound infection

- •Sources of organisms

- •Gram-positive organisms

- •Gram-negative organisms

- •Infection control

- •Pharmacological considerations in the treatment of burn infections

- •Topical antimicrobial treatment

- •Systemic antimicrobial treatment (Table 3)

- •Gram-positive bacterial infections

- •Enterococcal bacterial infections

- •Gram-negative bacterial infections

- •Treatment of yeast and fungal infections

- •The Polyenes (Amphotericin B)

- •Azole antifungals

- •Echinocandin antifungals

- •Nucleoside analog antifungal (Flucytosine)

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Acute treatment of severely burned pediatric patients

- •Introduction

- •Initial management of the burned child

- •Fluid resuscitation

- •Sepsis

- •Inhalation injury

- •Burn wound excision

- •Burn wound coverage

- •Metabolic response and nutritional support

- •Modulation of the hormonal and endocrine response

- •Recombinant human growth hormone

- •Insulin-like growth factor

- •Oxandrolone

- •Propranolol

- •Glucose control

- •Insulin

- •Metformin

- •Novel therapeutic options

- •Long-term responses

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Adult burn management

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology and aetiology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Assessment of the burn wound

- •Depth of burn

- •Size of the burn

- •Initial management of the burn wound

- •First aid

- •Burn blisters

- •Escharotomy

- •General care of the adult burn patient

- •Biological/Semi biological dressings

- •Topical antimicrobials

- •Biological dressings

- •Other dressings

- •Exposure

- •Deep partial thickness wound

- •Total wound excision

- •Serial wound excision and conservative management

- •Full thickness burns

- •Excision and autografting

- •Topical antimicrobials

- •Large full thickness burns

- •Serial excision

- •Mixed depth burn

- •Donor sites

- •Techniques of wound excision

- •Blood loss

- •Antibiotics

- •Anatomical considerations

- •Skin replacement

- •Autograft

- •Allograft

- •Other skin replacements

- •Cultured skin substitutes

- •Skin graft take

- •Rehabilitation and outcome

- •Future care

- •References

- •Burns in older adults

- •Introduction

- •Burn injury epidemiology

- •Pathophysiologic changes and implications for burn therapy

- •Aging

- •Comorbidities

- •Acute management challenges

- •Fluid resuscitation

- •Burn excision

- •Pain and sedation

- •End of life decisions

- •Summary of key points and recommendations

- •References

- •Acute management of facial burns

- •Introduction

- •Anatomy and pathophysiology

- •Management

- •General approach

- •Airway management

- •Facial burn wound management

- •Initial wound care

- •Topical agents

- •Biological dressings

- •Surgical burn wound excision of the face

- •Wound closure

- •Special areas and adjacent of the face

- •Eyelids

- •Nose and ears

- •Lips

- •Scalp

- •The neck

- •Catastrophic injury

- •Post healing rehabilitation and scar management

- •Outcome and reconstruction

- •Summary

- •References

- •Hand burns

- •Introduction

- •Initial evaluation and history

- •Initial wound management

- •Escharotomy and fasciotomy

- •Surgical management: Early excision and grafting

- •Skin substitutes

- •Amputation

- •Hand therapy

- •Secondary reconstruction

- •References

- •Treatment of burns – established and novel technology

- •Introduction

- •Partial thickness burns

- •Biological membranes – amnion and others

- •Xenograft

- •Full thickness burns

- •Dermal analogs

- •Keratinocyte coverage

- •Facial transplantation

- •Tissue engineering and stem cells

- •Gene therapy and growth factors

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Wound healing

- •History of wound care

- •Types of wounds

- •Mechanisms of wound healing

- •Hemostasis

- •Proliferation

- •Epithelialization

- •Remodeling

- •Fetal wound healing

- •Stem cells

- •Abnormal wound healing

- •Impaired wound healing

- •Hypertrophic scars and keloids

- •Chronic non-healing wounds

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Pain management after burn trauma

- •Introduction

- •Pathophysiology of pain after burn injuries

- •Nociceptive pain

- •Neuropathic pain

- •Sympathetically Maintained Pain (SMP)

- •Pain rating and documentation

- •Pain management and analgesics

- •Pharmacokinetics in severe burns

- •Form of administration [21]

- •Non-opioids (Table 1)

- •Paracetamol

- •Metamizole

- •Non-steroidal antirheumatics (NSAID)

- •Selective cyclooxygenasis-2-inhibitors

- •Opioids (Table 2)

- •Weak opioids

- •Strong opioids

- •Other analgesics

- •Ketamine (see also intensive care unit and analgosedation)

- •Anticonvulsants (Gabapentin and Pregabalin)

- •Antidepressants with analgesic effects

- •Regional anesthesia

- •Pain management without analgesics

- •Adequate communication

- •Psychological techniques [65]

- •Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

- •Particularities of burn pain

- •Wound pain

- •Breakthrough pain

- •Intervention-induced pain

- •Necrosectomy and skin grafting

- •Dressing change of large burn wounds and removal of clamps in skin grafts

- •Dressing change in smaller burn wounds, baths and physical therapy

- •Postoperative pain

- •Mental aspects

- •Intensive care unit

- •Opioid-induced hyperalgesia and opioid tolerance

- •Hypermetabolism

- •Psychic stress factors

- •Risk of infection

- •Monitoring [92]

- •Sedation monitoring

- •Analgesia monitoring (see Fig. 2)

- •Analgosedation (Table 3)

- •Sedation

- •Analgesia

- •References

- •Nutrition support for the burn patient

- •Background

- •Case presentation

- •Patient selection: Timing and route of nutritional support

- •Determining nutritional demands

- •What is an appropriate initial nutrition plan for this patient?

- •Formulations for nutritional support

- •Monitoring nutrition support

- •Optimal monitoring of nutritional status

- •Problems and complications of nutritional support

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •HBO and burns

- •Historical development

- •Contraindications for the use of HBO

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Nursing management of the burn-injured person

- •Introduction

- •Incidence

- •Prevention

- •Pathophysiology

- •Severity factors

- •Local damage

- •Fluid and electrolyte shifts

- •Cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and renal system manifestations

- •Types of burn injuries

- •Thermal

- •Chemical

- •Electrical

- •Smoke and inhalation injury

- •Clinical manifestations

- •Subjective symptoms

- •Possible complications

- •Clinical management

- •Non-surgical care

- •Surgical care

- •Coordination of care: Burn nursing’s unique role

- •Nursing interventions: Emergent phase

- •Nursing interventions: Acute phase

- •Nursing interventions: Rehabilitative phase

- •Ongoing care

- •Infection prevention and control

- •Rehabilitation medicine

- •Nutrition

- •Pharmacology

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Outpatient burn care

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology

- •Accident causes

- •Care structures

- •Indications for inpatient treatment

- •Patient age

- •Total burned body surface area (TBSA)

- •Depth of the burn

- •Pre-existing conditions

- •Accompanying injuries

- •Special injuries

- •Treatment

- •Initial treatment

- •Pain therapy

- •Local treatment

- •Course of treatment

- •Complications

- •Infections

- •Follow-up care

- •References

- •Non-thermal burns

- •Electrical injury

- •Introduction

- •Pathophysiology

- •Initial assessment and acute care

- •Wound care

- •Diagnosis

- •Low voltage injuries

- •Lightning injuries

- •Complications

- •References

- •Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of chemical burns

- •Chemical burns

- •Decontamination

- •Affection of different organ systems

- •Respiratory tract

- •Gastrointestinal tract

- •Hematological signs

- •Nephrologic symptoms

- •Skin

- •Nitric acid

- •Sulfuric acid

- •Caustic soda

- •Phenol

- •Summary

- •References

- •Necrotizing and exfoliative diseases of the skin

- •Introduction

- •Necrotizing diseases of the skin

- •Cellulitis

- •Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

- •Autoimmune blistering diseases

- •Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

- •Necrotizing fasciitis

- •Purpura fulminans

- •Exfoliative diseases of the skin

- •Stevens-Johnson syndrome

- •Toxic epidermal necrolysis

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Frostbite

- •Mechanism

- •Risk factors

- •Causes

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Rewarming

- •Surgery

- •Sympathectomy

- •Vasodilators

- •Escharotomy and fasciotomy

- •Prognosis

- •Research

- •References

- •Subject index

Nursing management of the burn-injured person

to be infected, with the organisms having invaded into viable tissue. Local signs of burn wound infection include a change in wound exudate, alteration in wound appearance, increase in wound pain, erythema, edema, cellulitis and induration at the wound edges. In the presence of a burn wound infection, a partial-thickness wound can convert to a full-thick- ness wound. If the organisms enter the lymphatic system, the patient can develop septicemia. Sepsis accounts for about 70% of deaths post-burn. Multisystem organ failure, often secondary to sepsis, is a serious and frequently fatal consequence of septicemia. Signs and symptoms of sepsis include an elevated temperature, increased pulse and respiratory rate, and decreased blood pressure and urinary output. The patient may become confused, feel and look unwell, have a diminished appetite and experience chills. It is important to identify and treat the source of sepsis as quickly as possible before multiple organ systems begin to fail. Cultures should be obtained from the blood, urine, sputum, invasive device sites and wounds. Intravenous antibiotics may then be ordered by the burn centre physicians, in consultation with the Infectious Disease service in the hospital. Initially, antibiotics can be ordered on speculation, pending culture and sensitivity reports from the lab. If necessary, the antibiotics may be changed to provide coverage specific to the organisms cultured. If the burn wounds, grafted areas or donor sites appear infected, topical antimicrobial coverage on the burn wound may need to be changed or instituted in order to provide treatment at a local level.

Clinical management

Non-surgical care

Therapeutic management of the burned person is conducted within these same three phases of burn recovery – emergent, acute and rehabilitative.

The emergent phase priorities include airway management, fluid therapy and initial wound care. The goals of care are initial assessment, management and stabilization of the patient during the first 48 hours post-burn.

Assessment: During the rapid, primary survey, performed soon after admission, the airway and breathing assume top priority. Particularly with a

large body surface area burn admission, some staff may feel a tendency to be overwhelmed by the sight and smell of the burn wound. The wounds are, however, a much lower priority than the airway. A compromised airway requires prompt attention and breath sounds verified in each lung field. If circumferential, full-thickness burns are present on the upper trunk and back, ventilation must be closely monitored as breathing might be impaired and releasing escharotomies necessary. The spine must be stabilized until c-spines are cleared. The circulation is assessed by examining skin colour, sensation, peripheral pulses and capillary filling. Circumferential, full-thickness burns to the arms or legs need to be assessed via palpation or doppler for evidence of adequate circulation. Escharotomies might be required. Typically, burn patients are alert and oriented during the first few hours post-burn. If that is not the case, consideration must be given to associated head injury, (including a complete neurological assessment), substance abuse, hypoxia or pre-existing medical conditions. All clothing and jewellery need to be removed in order to visualize the entire body and avoid the “tourniquet-like” effect of constricting items left in place as edema increases. Adherent clothing needs to be gently soaked off with normal saline to avoid further trauma and unnecessary pain. Attention then turns to prompt fluid resuscitation to combat the hypovolemic shock. The secondary, head-to-toe survey then rules out any associated injuries. A thorough assessment ensures all medical problems are identified and managed in a timely fashion. Circumstances of the injury should be explored as care can be influenced by the mechanism, duration and severity of the injury. The patient’s pertinent medical history includes identification of pre-existing disease or associated illness (cardiac or renal disease, diabetes, hypertension), medication/alcohol/drug history, allergies and tetanus immunization status. A handy mnemonic can be used to remember this information (Box 7).

Box 7. Secondary survey highlights

A |

allergies |

M |

medications |

P |

previous illness, past medical history |

L |

last meal or drink |

E |

events preceding injury |

|

|

403

J. Knighton, M. Jako

Management: The top priority of care is to stop the burning process (Box 8). During the initial first aid period at the scene, the patient must be removed from the heat source, chemicals should be brushed off and/or flushed from the skin, and the patient wrapped in a clean sheet and blanket ready for transport to the nearest hospital. Careful, local cooling of the burn wound with saline-moistened gauze can continue as long as the patient’s core temperature is maintained and he/she does not become hypothermic. Upon arrival at the hospital, the burned areas can be cooled further with normal saline, followed by a complete assessment of the patient and initiation of emergency treatment (Box 9). In a burn centre, the cooling may take place, using a cart shower system, in a hydrotherapy room (Fig. 12). The temperature of the water is adjusted to the patient’s comfort level, but tepid is usually best, while the wounds are quickly cleaned and dressings applied.

Airway management includes administration of 100% oxygen if burns are 20% body surface area or greater. Suctioning and ventilatory support may be necessary. If the patient is suspected of having or has an inhalation injury, intubation needs to be performed quickly. Circulatory management includes intravenous infusion of fluid to counteract the effects of hypovolemic shock for adult patients with burns > 15% body surface area and children with burns > 10% body surface area. Upon admission, 2 large bore, intravenous catheters should be in-

Box 8. First aid management at the scene

STEPS ACTION

Step 1 Stop the burning process – remove patient from heat source.

Step 2 Maintain airway – resuscitation measures may be necessary.

Step 3 Assess for other injuries and check for any bleeding.

Step 4 Flush chemical burns copiously with cool water.

Step 5 Flush other burns with cool water to comfort.

Step 6 Protect wounds from further trauma.

Step 7 Provide emotional support and have someone remain with patient to explain help is on the way.

Step 8 Transport the patient as soon as possible to nearby emergency department.

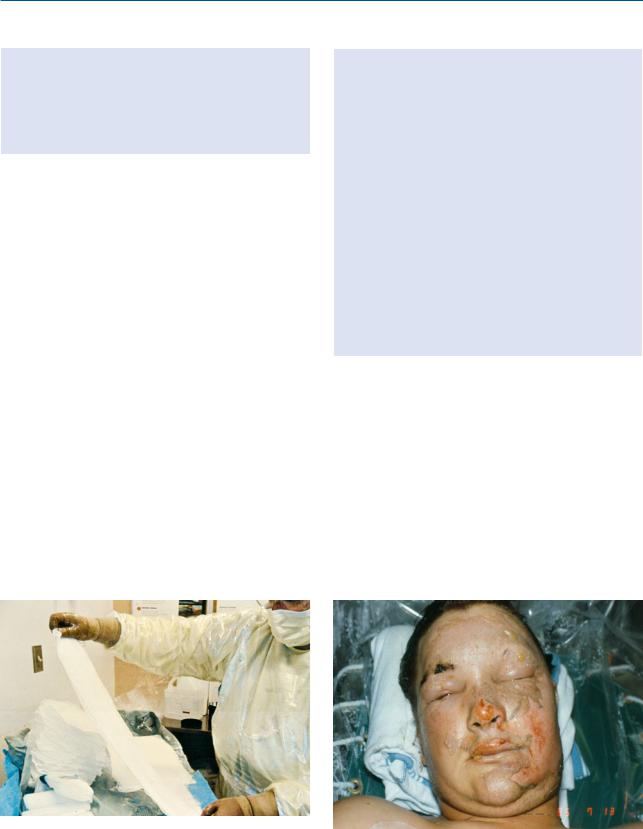

Fig. 12. Cart shower for hydrotherapy

serted, preferably into unburned tissue. However, if the only available veins are in a burned area, they should be used. Patients who have large burns, where intravenous access will be necessary for a number of days, benefit from a central venous access device inserted into either the subclavian, jugular or femoral

Box 9. Treatment of the severely burned patient on admission

STEPS ACTION

Step 1 Stop the burning process.

Step 2 Establish and maintain an airway; inspect face and neck for singed nasal hair, soot in the mouth or nose, stridor or hoarseness.

Step 3 Administer 100% high flow humidified oxygen by non-rebreather mask. Be prepared to intubate if respiratory distress increases.

Step 4 Establish intravenous line(s) with large bore cannula(e) and initiate fluid replacement using Lactated Ringer’s solution.

Step 5 Insert an indwelling urinary catheter.

Step 6 Insert a nasogastric tube.

Step 7 Monitor vital signs including level of consciousness and oxygen saturation.

Step 8 Assess and control pain.

Step 9 Gently remove clothing and jewellery.

Step 10 Examine and treat other associated injuries.

Step 11 Assess extremities for pulses, especially with circumferential burns.

Step 12 Determine depth and extent of the burn.

Step 13 Provide initial wound care – cool the burn and cover with large, dry gauze dressings.

Step 14 Prepare to transport to a burn centre as soon as possible.

404

Nursing management of the burn-injured person

vein. The overall goal is to establish an access route that will accommodate large volumes of fluid for the first 48 hours post-burn. The aim of fluid resuscitation is to maintain vital organ function, while avoiding the complications of inadequate or excessive therapy. Fluid calculations are based on the extent of the burn, the weight and age of the patient, pre-burn conditions (dehydration) or pre-existing chronic illnesses (respiratory, renal). The most commonly used fluid resuscitation regimen is the Parkland (Baxter) formula (Box 10). It involves the use of crystalloid (Lactated Ringer’s) solution. Fluids are calculated for the first 24 hours post-burn with “0” hours being the time of the burn, not the time of admission to hospital. One-half of the 24 hour total needs to be administered over the first 8 hours post-burn as this is the period during which extravasation of fluid into the interstitial space is greatest, along with the risk of renal tubule blockage from hemoglobin and myoglobin pigments. The remaining half of the estimated resuscitation volume should be administered over the subsequent 16 hours of the first post-burn day. It is important to remember that the formula is only a guideline. The infusion needs to be adjusted based on the patient’s clinical response, which includes vital signs, sensorium and urinary output. For adults, 30–50 mL urine per hour is the goal and 1 mL/kg/hr in children weighing less than 30 kg. An indwelling urinary catheter needs to be inserted at the same time as the IV’s are established in order to reliably measure the adequacy of the fluid resuscitation [9]. Vital signs should be trending around a systolic BP of ≥ 90 to 100 mg Hg, a pulse rate of < 120

for the older child/adult, < 140 bpm in the child between 2–5 years of age and < 160 bpm in the child under 2 years of age, with respirations at 16–20 breaths/minute. The patient’s sensorium should be such that he/she is alert and oriented to time, person and place. An exception is made regarding the sensorium assessment for the intubated patient. During the second 24 hours post-burn, the need for aggressive fluid resuscitation is generally less as capillary permeability begins to return to normal. Colloids, such as albumin, can be given as volume expanders to replace lost protein and minimize ongoing fluid requirements. Earlier administration of colloid would result in leakage out of the vascular space because of the increased capillary permeability. Some patients require extra fluid above and beyond the formula guidelines in order to produce satisfactory urinary output, stable vital signs and an adequate sensorium. They include those with a) high voltage injury, b) inhalation injury, c) delayed resuscitation, or d) prior dehydration. Those patients with a high voltage injury require administration of a diuretic to produce a urinary output of 75–100 mL/hour in order to clear the tubules of hemoglobin and myoglobin pigments. The usual choice is Mannitol 12.5 gram/litre of fluid. Since the heme pigments are more soluble in an alkaline medium, sodium bicarbonate can be added to the resuscitation fluid as needed to maintain a slightly alkaline urine. Patients with severe inhalation injury and body surface area burns may require 40–50% more fluid in order to achieve adequate tissue perfusion. The need for extra fluid must be balanced against the risk of pulmonary ede-

Box 10. Fluid resuscitation using the Parkland (Baxter) formula

Formula |

Administration |

Example |

4 mL Lactated Ringer’s solution per kg body |

½ total in first 8 hours |

For a 65 kg patient with a 40 % burn injured |

weight per % total body surface area (TBSA) |

¼ total in second 8 hours |

at 1000 hours: |

burn |

¼ total in third 8 hours |

4 mL x 65 kg x 40% burn = 10,400 mL in first |

= |

|

24 hours |

total fluid requirements for the first 24 hours |

|

½ total in first 8 hours (1000-1800 hours) |

post-burn (0 hours = time of injury) |

|

= 5200 mL (650 mL/hr) |

|

|

¼ total in second 8 hours (1800-0200 hours) |

|

|

= 2600 mL (325 mL/hr) |

|

|

¼ total in third 8 hours (0200-1000 hours) |

|

|

= 2600 mL (325 mL/hr) |

N.B. Remember that the formula is only a guideline. Titrate to maintain urinary output at 30–50 mL/hr, stable vital signs and adequate sensorium.

405

J. Knighton, M. Jako

ma and “fluid creep”/overload[10]. There are others who are considered “volume sensitive”. They are a) ≥ 50 years of age, b) ≤ 2 years of age, or c) have preexisting cardiopulmonary or renal disease. Particular caution must be exercised with these patients.

Wound care. Once a patent airway, adequate circulation and fluid replacement have been established, attention can turn to wound care and the ultimate long-term goal of wound closure. Such closure will halt or reverse the various fluid/electrolyte, metabolic and infectious processes associated with an open burn wound. The burns are gently cleansed with normal saline, if the care is being provided on a stretcher or bed. If a hydrotherapy cart shower or immersion tank are used, tepid water cleans the wounds of soot and loose debris (Fig. 13).

Sterile water is not necessary. Chemical burns should be flushed copiously for at least 20 minutes, preferably longer. Tar cannot be washed off the wound. It requires numerous applications of an emulsifying agent, such as Tween 80 , Medisol or Polysporin ointment. After several applications, the tar will have been removed without unnecessary trauma to healthy tissue. During hydrotherapy, loose, necrotic tissue (eschar) may be gently removed (debrided) using sterile scissors and forceps. Hair-bear- ing areas that are burned should be carefully shaved, with the exception of the eyebrows. This serves to minimize the accumulation of organisms. Showering or bathing should be limited to 20 minutes in

Fig. 13. Initial wound care post-admission

order to minimize patient heat loss and physical/ emotional exhaustion. More aggressive debridement should be reserved for the operating room, unless the patient receives conscious sedation. After the initial bath or shower, further decisions are made regarding wound care. There are three methods of treatment used in caring for burn wounds. In the open method, the wound remains exposed, with only a thin layer (2.0 mm to 4.0 mm) of topical antimicrobial ointment spread on the wound surface using a sterile gloved hand or applicator. With the closed method, a dressing is left intact for two to seven days. The most common approach is to make multiple dressing changes, usually twice a day. The frequency depends on the condition of the wound and the properties of the dressing employed. The choice of treatment method varies among institutions and also according to the severity of the burn wound. All treatment approaches have certain objectives in common (Table 6). In the emergent phase, wounds are generally treated with a thin layer of topical antimicrobial cream. Topical coverage is selected according to the condition of the wound, desired results, and properties of the topical agent (Table 7). Assessment criteria have been established for choosing the most appropriate agent (Box 11). The most commonly selected topical antimicrobial agent is silver sulphadiazene, which can be applied directly to saline-moistened gauze, placed on the wound, covered with additional dry gauze or a burn pad, and secured with gauze wrap or flexible netting (Fig. 14). These dressings are usually changed twice a day. If the hydrotherapy room is used for the morning dressing change, the evening dressing is done in the patient’s room as it is too physically and emotionally exhausting to shower the burned person twice daily. It is preferred that the antimicrobial be applied directly to the gauze as opposed to being spread on the wound for two reasons: it is less likely that you will spread organisms from one part of a burn wound to another and it is generally less painful for the patient. Patients lose a lot of body heat during dressing changes, so it is advised that the temperature of the room be elevated slightly and that only small to moderate-sized areas of the body be exposed at any one time. Cartilagenous areas, such as the nose and ears, are usually covered with mafenide acetate (Sulfamylon ), which has greater eschar penetration

406

|

Nursing management of the burn-injured person |

Table 6. Objectives of burn wound care |

|

Objective |

Rationale |

Prevention of conversion |

Wounds that dry out or develop an infection can become deeper. A partial-thickness wound could |

|

then convert to full-thickness and require skin grafting. |

Removal of devitalized |

Debridement, either through dressing changes or surgery, is necessary to clean the wounds and |

tissue |

prepare for spontaneous healing or grafting. |

Preparation of healthy |

Healthy tissue, free of eschar and nourished by a good blood supply, is essential for new skin |

granulation tissue |

formation. |

Minimization of |

Eschar contains many organisms. Removal is essential in order to decrease the bacterial load and |

systemic infection |

reduce the risk of burn wound infection. |

Completion of the |

Full-thickness wounds require the application of autologous skin grafts from available donor sites. |

autografting process |

|

Limitation of scars and |

Wounds that heal well the first time tend to have fewer scars and contractures. Some degree of scar |

contractures |

and contracture formation are, however, part of the healing process and cannot be entirely prevented. |

ability. Face care includes the application of warmed, saline-moistened gauze to the face for 20 minutes, followed by a gentle cleansing and reapplication of a thin layer of ointment, such as polymyxin B sulphate (Polysporin ) (Fig. 15). A number of silver-impregnat- ed dressings (Acticoat /Acticoat Flex, AQUACEL Ag) have also been commonly used in the emergent phase of burn wound care. These dressings are mois-

tened with sterile water, placed on a burn wound and left intact anywhere from 3–4 days to as long as 21 days, depending on the patient’s individual clinical status and particular product.

Infection may develop under the eschar as a result of organisms that were present deep in ducts or on adjacent areas which were not destroyed at the time of the burn. Topical antimicrobial coverage is

Table 7. Topical antimicrobial agents used on burn wounds

Product |

Preparation |

Antimicrobial Action |

Applications |

Silver sulphadiazene |

1% water-soluble |

Broad-spectrum antimicrobial |

Burn wound: |

(SSD , Silvadene , |

cream |

activity |

Applied using the open or closed |

Flamazine ) |

|

Poor solubility with limited |

dressing method of wound care. |

|

|

diffusion into eschar. |

|

Mafenide acetate |

8.5% water-soluble |

Bacteriostatic for gram-positive |

Deep partial-thickness and full-thickness burns: |

(Sulfamylon ) |

cream |

and gram-negative organisms. |

Applied using either the open (exposure) |

|

|

Highly soluble and diffuses |

or closed (occlusive) dressing method. |

|

|

through the eschar. |

Graft site: |

|

|

|

Saturated dressings are applied. |

|

5% solution |

Same as above |

|

Silver Nitrate |

0.5% solution |

Broad-spectrum antimicrobial |

Burn wound or graft site: |

|

|

activity |

Saturated, multi-layered dressings are |

|

|

Hypotonic solution |

applied to the wound or grafted surface. |

Petroleum and |

Neosporin (neomyBactericidal for a variety of |

Superficial burn wound: |

|

mineral oil-based |

cin, bacitracin, |

gram-positive and gram-negative |

Applied to wound in a thin (1 mm) layer. |

antimicrobial |

polymyxin B); |

organisms. |

Should be reapplied as needed to keep |

ointments (e.g. |

Bacitracin |

Ointments have limited ability to |

ointment in contact with wound. |

Neosporin , |

(bacitracin zinc); |

penetrate eschar. |

|

Bacitracin , |

Polysporin (baci- |

|

|

Polysporin ) |

tracin, |

|

|

|

polymyxin B) |

|

|

407

J. Knighton, M. Jako

Box 11. Properties of topical antimicrobial agents

Readily available

Pharmacologic stability

Sensitivity to specific organisms

Non-toxic

Cost effective

Non-painful on application

Capability of eschar penetration

selected according to the condition of the wound and desired results and properties of the topical agent. Whatever topical and dressing strategies are chosen, basic aseptic wound management techniques must be followed. Personnel need to wear isolation gowns over scrub suits, masks, head covers and clean, disposable gloves to remove soiled dressings or cleanse wounds. Sterile gloves should be used when applying inner dressings or ointment to the face. The choice of dressings should take into consideration the condition of the wound, desired clinical results, the properties of the particular dressing, physician preference and availability in each burn centre. There are currently a number of biologic, biosynthetic and synthetic wound coverings available. The ideal dressing should possess particular criteria (Box 12). During the first few days post-burn, the wounds are examined to determine actual depth. It usually takes a few days for deep, partial-thickness wounds to “declare” themselves. Some wounds are deeper than they initially appear on admission. Scald

Box 12. Criteria for burn wound coverings

Absence of antigenicity

Tissue compatibility

Absence of local and systemic toxicity

Water vapour transmission similar to normal skin

Impermeability to exogenous micro-organisms

Rapid and sustained adherence to wound surface

Inner surface structure that permits in-growth of fibrovascular tissue

Flexibility and pliability to permit conformation to irregular wound surface; elasticity to permit motion of underlying body tissue

Resistance to linear and shear stresses

Prevention of proliferation of wound surface flora and reduction of bacterial density of the wound

Tensile strength to resist fragmentation and retention of membrane fragments when removed

Biodegradability (important for “permanently” implanted membranes)

Low cost

Indefinite shelf life

Minimal storage requirements and easy delivery

injuries are almost always deeper than they appear on admission and need to be closely monitored. A treatment plan is then developed to ultimately close the burn wound, either through surgical or non-sur- gical means.

The focus of therapy in the acute phase is the management of any complications which might arise during the recovery period and closure of the burn wound. This phase can have a duration of anywhere from a week to several months. Com-

Fig. 14. Applying silver sulphadiazene cream to saline- |

|

moistened gauze |

Fig. 15. Facial burn wound care |

408

Nursing management of the burn-injured person

mencement of this phase begins with the onset of spontaneous diuresis and return of fluid to the intravascular space.

Assessment: The focus of attention is on the continued need for fluid therapy, wound care, physiotherapy and occupational therapy, pain and anxiety management. Fluid therapy is administered in accordance with the patient’s fluid losses and medication administration. Wounds are examined on a daily basis and adjustments made to the plan of care. The colour, drainage, odour, appearance and amount of pain are noted on a wound assessment and treatment record. If a wound is full-thick- ness, arrangements need to be made to take the patient to the operating room for surgical excision and grafting.

The physiotherapist and occupational therapist will see the patients daily and revise their plan of care accordingly. The plan of care is understandably different if the patient is critically ill versus acutely ill but ambulatory. Efforts are made to adapt the care around major treatments, such as O. R.’s, when the patient will be on bed-rest for a number of days. The patient’s level of pain and anxiety need to be measured and responded to on a daily basis. A variety of pharmacologic strategies are available (Table 8) and require the full commitment of the burn team in order to be most effective. It is helpful to have multiple modalities of medications to handle both the background discomfort from burn injury itself and the intense pain inflicted during procedural and rehabilitative activities.

Table 8. Sample burn pain management protocol

RECOVERY PHASE |

TREATMENT |

CONSIDERATIONS |

||

Critical/acute with mild to |

– |

IV morphine continuous infusion i.e. |

– |

Assess patient’s level of pain q 1h using VAS |

moderate pain experience |

|

2–4 mg q 1h |

|

(0–10) |

|

– |

bolus for breakthrough i.e. 1/3 continu- |

– |

Assess patient’s response to medication and |

|

|

ous infusion hourly dose. |

|

adjust as necessary |

|

– |

Bolus for acutely painful episodes/ |

– |

Assess need for anti-anxiety agents i.e. Ativan®, |

|

|

mobilization, i.e. 3 x continuous infusion |

|

Versed® |

|

|

hourly dose; consider hydromorphone or |

– |

Relaxation exercises |

|

|

fentanyl if morphine ineffective. |

– |

Music distraction |

Critical/acute with severe |

1. |

IV Morphine |

– |

Consider fentayl infusion for short-term |

pain experience |

– continuous infusion for background pain |

|

management of severe pain |

|

|

|

i.e. 2–4 mg q 1h |

– Assess level of pain q1h using VAS |

|

|

– |

bolus for breakthrough |

– |

Assess level of sedation using SASS score |

|

2. |

IV fentanyl |

– |

Relaxation exercises |

|

– |

bolus for painful dressing changes/ |

– |

Music distraction |

|

|

mobilization |

– |

Assess need for anti-anxiety/sedation agents i.e. |

|

3. IV Versed® |

|

Ativan®, Versed®. |

|

|

– |

bolus for extremely painful dressing |

|

|

|

|

change/mobilization |

|

|

|

4. |

Propofol Infusion |

|

|

|

– consult with Department of Anaesthesia |

|

|

|

|

|

for prolonged and extremely painful |

|

|

|

|

procedures i.e. major staple/ dressing |

|

|

|

|

removal |

|

|

Later acute/rehab with |

– |

Oral continuous release morphine or |

– |

Assess level of pain q1h using VAS |

mild to moderate pain |

|

hydromorphone – for background pain |

– Consult equianalgesic table for conversion |

|

experience |

|

BID |

|

from I.V. to P.O. |

|

– Oral morphine or hydromorphone for |

– Assess for pruritis |

||

|

|

breakthrough pain and dressing change/ |

|

|

|

|

mobilization |

|

|

|

– |

Consider adjuvant analgesics such as |

|

|

|

|

gabapentin, ketoprofen, ibuprofen, |

|

|

|

|

acetaminophen |

|

|

409

J. Knighton, M. Jako

Management: Selecting the most appropriate method to close the burn wound is by far the most important task in the acute period. However, the team needs to be able to respond quickly to a patient’s change in clinical status as he/she can become very sick despite an improvement in wound status. Commonfluid replacement choicesincludeintravenous normal saline, glucose in saline or water, or Lactated Ringer’s solution. On occasion, albumin, plasma and packed red blood cells might be given. Central lines, with multiple lumens, are essential when administering fluids and multiple medications simultaneously.

Wound care is performed daily and treatments adjusted according to the changing condition of the wounds (Table 9). During the dressing changes, nurses debride small amounts of loose tissue for a short period of time, ensuring that the patient is receiving adequate analgesia and sedation. A constant dialogue needs to take place between the nursing and medical staff to ensure the right medication in the right amount is available for each and every patient to avoid needless suffering by patients who live in fear of each dressing change. That preoccupation interferes with their ability to perform self-care and reduces their existence to a state of misery, both of which are unacceptable and unnecessary in the world of burn care today. As the eschar is removed from the areas of partial-thickness burn, the type of dressing selected is based on its ability to promote moist wound healing. There are biologic, biosynthetic and synthetic dressings and skin substitutes available today (Table 10). Areas of full-thickness damage require surgical excision and skin grafting. There are specific dressings appropriate for grafted areas and donor sites.

Physiotherapy and occupational therapy are an important part of a patient’s daily plan of care. Depending on the patient’s particular needs and stage of recovery, there are certain range-of-motion exercises, ambulation activities, chest physiotherapy, stretching and splinting routines to follow. The program adjusts on a daily/weekly basis as the patient makes progress towards particular goals and as his/ her clinical condition improves or worsens. Pain and anxiety management are critical in the acute period of care. Many of the activities a patient is required to do in order to get well cause him/her a degree of dis-

comfort. The ongoing nature of the pain and the unfamiliar world of burn care can quickly exhaust a patient’s pre-burn coping strategies. Establishment of unit-based protocols that can be adjusted to meet each patient’s individual needs assists greatly in managing the pain and anxiety so often associated with burn care.

The focus of therapy during the rehabilitative phase is directed towards working with the patient to return him/her to a state of optimal physical and psychosocial functioning. The clinical focus in on ensuring all open wounds eventually close, observing and responding to the development of scars and contractures, and ensuring that there is a plan for future reconstructive surgical care, if the need exists. The transition from hospital to home or to a rehabilitation facility is a difficult one for most burn survivors and their family members to make. Although they are given information as to what to expect on a number of occasions by various members of the burn team and reassured that things will be fine, predischarge anxiety levels can run high. Wound care is generally fairly simple at this time. Dressings should be minimal or non-existent. Most of the wounds should have healed or be very small. Frustration may result, however, when the patient realizes that his healed skin in still quite fragile and can break down with very little provocation. The need to moisturize the skin with water-based creams is emphasized in order to keep the skin supple and to decrease the itchiness that may be present. As the burn patient prepares to leave the protective environment of the burn centre, numerous feelings may be experienced. Burn team members need to be sensitive to and encourage patients to verbalize concerns and questions. The burned person may experience feelings of uncertainty, fear and anxiety about what lies ahead, decreased confidence following weeks and, perhaps, months of dependence on hospital staff, along with concerns about coping with treatment protocols and impaired physical mobility. Some may have to reenter society with an altered body image and decreased sense of self-esteem. Ongoing counselling to assist with adjusting to an altered appearance and a dramatic change in one’s life plan is a very necessary part of post-discharge care. Nervousness about returning home after a prolonged absence and concerns about resumption of previous roles and re-

410

|

|

Nursing management of the burn-injured person |

Table 9. Sample burn wound management protocol |

|

|

WOUND STATUS |

TREATMENT |

CONSIDERATIONS |

Early acute; partial |

– Silver Sulphadiazene – impregnated gauze |

– Apply thin layer (2-3mm) of Silver Sulphadia- |

or full – thickness; |

saline-moistened gauze |

zene to avoid excessive build up. |

eschar/blisters |

dry gauze – outer wrap |

– Monitor for local signs of infection i.e. purulent |

present |

– Mafenide acetate (Sulfamylon ) to cartilagenous areas of |

drainage, odour and notify M.D. re. potential |

|

face i.e. nose, ears polymyxin B sulphate (Polysporin ) |

need for alternative topical agents i.e. acetic |

|

ointment to face |

acid, mafenide acetate. |

|

– Change BID to body; face care q4h |

|

Mid-acute; partial |

– Saline – moistened gauze dry gauze – outer wrap |

– Saline dressings to be applied to a relatively |

or full-thickness; |

– Change BID |

small area due to potentially painful nature of |

leathery or cheesy |

– Full-thickness wounds to be excised surgically |

treatment |

eschar remaining |

|

– Potential use of enzymatic debriding agents |

|

|

(Collagenase Santyl , Elase , Accuzyme ) |

|

|

– Monitor for local signs of infection and notify |

|

|

M.D. |

Late acute; clean |

– Non-adherent greasy gauze dressing (Jelonet , Adaptic ) |

– Monitor for local signs of infection and notify |

partial-thickness |

Saline-moistened gauze dry gauze – outer wrap |

M.D. |

wound bed |

– Change once daily |

|

Post-op graft site |

– Non-adherent greasy gauze dressing (Jelonet , Adaptic ) |

– Select appropriate pressure-relieving sleep |

|

Saline–moistened gauze dry gauze outer wrap |

surface |

|

– Leave intact x4 days |

– Monitor for local signs of infection and notify |

|

– Post-op day 4, gently debulk to non-adherent gauze layer |

M.D. |

|

redress once daily |

|

|

– Post-op day 5, gently debulk to grafted area |

|

|

redress once daily |

|

Early rehab; healed |

– polymyxin B sulphate (Polysporin ) ointment until |

– Apply thin layer (2mm) of polymyxin B sulphate |

partial-thickness or |

wound stable BID |

(Polysporin ) ointment to avoid excessive |

graft site |

– When stable, moisturizing cream applied BID and prn |

build-up |

|

|

– Avoid lanolin and mineral-oil containing creams |

|

|

which clog epidermal pores and don’t reach dry, |

|

|

dermal layer |

Post-op donor site |

– Hydrophilic foam dressing (i.e. Allevyn , Mepilex ) or |

– Monitor for local signs of infection and notify |

|

medicated greasy gauze dressing (i.e. Xeroform ) |

M.D. |

|

– Cover foam with transparent film dressing and pressure |

|

|

wrap x 24 hrs |

|

|

– Remove wrap and leave dressing intact until day 4; |

|

|

replace on day 4 and leave intact until day 8. Remove |

|

|

and inspect |

|

|

– If wound unhealed, reapply a second foam dressing |

|

|

– If healed, apply polymyxin B suphate (Polysporin ) |

|

|

ointment BID |

|

|

– When stable, apply moisturizing cream BID and prn |

|

|

– Cover Xeroform with dry gauze and secure. Leave intact |

|

|

for 5 days. |

|

|

– Remove outer gauze on day 5 and leave open to air. Apply |

|

|

light layer of polymyxin B sulphate (Polysporin )ointment. |

|

|

If moist, reapply gauze dressing for 2–3 more days. |

|

|

– When Xeroform dressing lifts up as donor site heals, |

|

|

trim excess and apply polymyxin B sulphate (Polysporin ) |

|

|

ointment |

|

Face |

– Normal saline-moistened gauze soaks applied to face x15 |

– For male patients, carefully shave beard area on |

|

minutes |

admission and as necessary to avoid build-up of |

|

– Remove debris gently using gauze |

debris. Scalp hair may also need to be clipped |

|

– Apply thin layer of polymyxin B sulphate (Polysporin ) |

carefully on admission to inspect for any burn |

|

ointment |

wounds. |

|

– Repeat soaks q 4–6 h |

|

|

– Apply light layer of mafenide acetate (Sulfamylon ) |

|

|

cream to burned ears and nose cartilage |

|

411

J. Knighton, M. Jako

Table 10. Temporary and permanent skin substitutes

BIOLOGICAL |

BIOSYNTHETIC |

SYNTHETIC |

||

Temporary |

Temporary |

Temporary |

||

Allograft/Homograft (cadaver skin) |

Nylon polymer bonded to silicone |

Polyurethane and polyethylene thin |

||

– clean, partial and full-thickness burns |

|

membrane with collagenous porcine |

|

film (OpSite , Tegaderm , Omiderm , |

Amniotic membrane |

|

peptides (BioBrane ) |

|

Bioclusive |

– clean, partial thickness burns |

– |

Clean, partial-thickness burns, donor |

Composite polymeric foam (Allevyn , |

|

Xenograft (pigskin) |

|

sites |

|

Mepilex , Curafoam , Lyofoam ) |

– clean partial and full-thickness burns |

Calcium alginate from brown seaweed |

– |

clean, partial-thickness burns, donor |

|

|

|

(Curasorb , Kalginate ) |

|

sites |

|

– |

exudative wounds, donor sites |

Nonadherent gauze (Jelonet , |

|

|

Human dermal fibroblasts cultured |

|

Xeroform , Adaptic ) |

|

|

|

onto BioBrane (TransCyte ) |

– |

clean partial-thickness burns, skin |

|

– |

clean, partial-thickness burns |

|

grafts, donor sites |

Mesh matrix of oat beta-glucan and

collagen attached to gas-permeable polymer (BGC Matrix )

–clean, partial-thickness burns, donor sites

Semi-permanent |

Semi-permanent |

|

Mixed allograft seeded onto widely- |

Bilaminar membrane of bovine |

|

|

meshed autograft |

collagen and glycosaminoglycan |

– |

clean, full-thickness burns |

attached to Silastic layer (Integra ) |

Permanent |

– clean, full-thickness burns |

|

|

||

Cultured epithelial autografts (CEA) |

|

|

|

grown from patient’s own keratinoc- |

|

|

ytes (Epicel ) |

|

– |

clean, full-thickness burns |

|

Allograft dermis decellularized, freeze-dried and covered with thin

autograft or cultured keratinocytes (AlloDerm )

– clean, full-thickness burns

sponsibilities may also be experienced. If the burn survivor is being transferred to a rehabilitation facility, concerns are often expressed about adjusting to a new environment where one is unfamiliar with staff and routines. Anticipating these concerns and talking with patients and families before the transition occurs is an important part of the plan of care. Support to family is also important as they will assume the primary caretaker role once held by members of the burn team. Home care may need to be arranged and those health team members can bear some of the burden of care until the patient is more self-suffi- cient. Community-based caregivers can also alleviate some of the anxieties of family members. Visits to the outpatient burn clinic serve as important connections for staff, patients and family and provide an

opportunity to have questions and concerns answered, to receive feedback on progress to date, and to talk about changes in the treatment plan. The occupational therapist plays an important role in the rehabilitation period for this is the time when scar maturation begins and contractures may worsen. Scar management techniques, including pressure garments, inserts, massage and stretching exercises, need to be taught to patients and their importance reinforced with each and every visit. Encouragement is also essential in order to keep patients and families motivated, particularly during the times when progress is slow and there seems to be no end in sight to the months of therapy. The burn surgeon can also plan future reconstructive surgeries for the patient, taking into consideration what

412