- •Preface to the First Edition

- •Preface to the Second Edition

- •Contents

- •Diagnostic Challenges

- •Expert Centers

- •Patient Organizations

- •Clinical Trials

- •Research in Orphan Lung Diseases

- •Orphan Drugs

- •Orphanet

- •Empowerment of Patients

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Challenges to Overcome in Order to Undertake Quality Clinical Research

- •Lack of Reliable Data on Prevalence

- •Small Number of Patients

- •Identifying Causation/Disease Pathogenesis

- •Disease Complexity

- •Lack of Access to a Correct Diagnosis

- •Delay in Diagnosis

- •Challenges But Not Negativity

- •Some Success Stories

- •The Means to Overcome the Challenges of Clinical Research: Get Bigger Numbers of Well-Characterized Patients

- •The Importance of Patient Organizations

- •National and International Networks

- •End Points for Trials: Getting Them Right When Numbers Are Small and Change Is Modest

- •Orphan Drug Development

- •Importance of Referral Centers

- •Looking at the Future

- •The Arguments for Progress

- •Concluding Remarks

- •References

- •3: Chronic Bronchiolitis in Adults

- •Introduction

- •Cellular Bronchiolitis

- •Follicular Bronchiolitis

- •Respiratory Bronchiolitis

- •Airway-Centered Interstitial Fibrosis

- •Proliferative Bronchiolitis

- •Diagnosis

- •Chest Imaging Studies

- •Pulmonary Function Testing

- •Lung Biopsy

- •Mineral Dusts

- •Organic Dusts

- •Volatile Flavoring Agents

- •Infectious Causes of Bronchiolitis

- •Idiopathic Forms of Bronchiolitis

- •Connective Tissue Diseases

- •Organ Transplantation

- •Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

- •Drug-Induced Bronchiolitis

- •Treatment

- •Constrictive Bronchiolitis

- •Follicular Bronchiolitis

- •Airway-Centered Interstitial Fibrosis

- •Proliferative Bronchiolitis

- •References

- •Background and Epidemiology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Host Characteristics

- •Clinical Manifestations

- •Symptoms

- •Laboratory Evaluation

- •Skin Testing

- •Serum Precipitins

- •Eosinophil Count

- •Total Serum Immunoglobulin E Levels

- •Recombinant Antigens

- •Radiographic Imaging

- •Pulmonary Function Testing

- •Histology

- •Diagnostic Criteria

- •Historical Diagnostic Criteria

- •Rosenberg and Patterson Diagnostic Criteria

- •ISHAM Diagnostic Criteria

- •Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Diagnostic Criteria

- •General Diagnostic Recommendations

- •Allergic Aspergillus Sinusitis (AAS)

- •Natural History

- •Treatment

- •Corticosteroids

- •Antifungal Therapy

- •Monoclonal Antibodies

- •Monitoring for Treatment Response

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •5: Orphan Tracheopathies

- •Introduction

- •Anatomical Considerations

- •Clinical Presentation

- •Etiological Considerations

- •Idiopathic Subglottic Stenosis

- •Introduction

- •Clinical Features

- •Pulmonary Function Studies

- •Imaging Studies

- •Bronchoscopy

- •Treatment

- •Introduction and Clinical Presentation

- •Clinical Features

- •Pulmonary Function Studies

- •Imaging Studies

- •Bronchoscopy

- •Treatment

- •Tracheomalacia

- •Introduction

- •Clinical Features

- •Pulmonary Function Studies

- •Imaging Studies

- •Bronchoscopy

- •Treatment

- •Tracheobronchomegaly

- •Introduction

- •Clinical Features

- •Pathophysiology

- •Pulmonary Function Studies

- •Imaging Studies

- •Treatment

- •Tracheopathies Associated with Systemic Diseases

- •Relapsing Polychondritis

- •Introduction

- •Clinical Features

- •Laboratory Findings

- •Pulmonary Function and Imaging Studies

- •Treatment

- •Introduction

- •Clinical Features

- •Pulmonary Function Studies

- •Imaging Studies

- •Bronchoscopy

- •Treatment

- •Tracheobronchial Amyloidosis

- •Introduction

- •Clinical Features

- •Pulmonary Function Studies

- •Imaging Studies

- •Bronchoscopy

- •Treatment

- •Sarcoidosis

- •Introduction

- •Pulmonary Function Studies

- •Imaging Studies

- •Bronchoscopy

- •Treatment

- •Orphan Tracheopathies: Conclusions

- •References

- •6: Amyloidosis and the Lungs and Airways

- •Introduction

- •Diagnosis and Evaluation of Amyloidosis

- •Systemic AA Amyloidosis

- •Systemic AL Amyloidosis

- •Amyloidosis Localised to the Respiratory Tract

- •Laryngeal Amyloidosis

- •Tracheobronchial Amyloidosis

- •Parenchymal Pulmonary Amyloidosis

- •Pulmonary Amyloidosis Associated with Sjögren’s Disease

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Pathophysiology

- •Genetic Predisposition

- •Immune Dysregulation

- •Epidemiology

- •Incidence and Prevalence

- •Triggering Factors

- •Clinical Manifestations

- •General Symptoms

- •Pulmonary Manifestations

- •Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) Manifestations

- •Neurological Manifestations

- •Skin Manifestations

- •Cardiac Manifestations

- •Gastrointestinal Involvement

- •Renal Manifestations

- •Ophthalmological Manifestations

- •Complementary Investigations

- •Diagnosis

- •Diagnostic Criteria

- •Prognosis and Outcomes

- •Phenotypes According to the ANCA Status

- •Treatment

- •Therapeutic Strategies

- •Remission Induction

- •Maintenance Therapy

- •Other Treatments

- •Prevention of AEs

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •8: Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

- •A Brief Historical Overview

- •Epidemiology

- •Pathogenesis

- •Clinical Manifestations

- •Constitutional Symptoms

- •Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) Manifestations

- •Pulmonary Manifestations

- •Kidney and Urological Manifestations

- •Kidney Manifestations

- •Urological Manifestations

- •Neurological Manifestations

- •Peripheral Nervous System (PNS) Manifestations

- •Central Nervous System (CNS) Manifestations

- •Spinal Cord and Cranial Nerve Involvement

- •Skin and Oral Mucosal Manifestations

- •Eye Manifestations

- •Cardiac Involvement

- •Gastrointestinal Manifestations

- •Gynecological and Obstetric Manifestations

- •Venous Thrombosis and Other Vascular Events

- •Other Manifestations

- •Pediatric GPA

- •Diagnosis

- •Diagnostic Approach

- •Laboratory Investigations

- •Biology

- •Immunology

- •Pathology

- •Treatment

- •Glucocorticoids

- •Cyclophosphamide

- •Rituximab

- •Other Current Induction Approaches

- •Other Treatments in GPA

- •Intravenous Immunoglobulins

- •Plasma Exchange

- •CTLA4-Ig (Abatacept)

- •Cotrimoxazole

- •Other Agents

- •Principles of Treatment for Relapsing and Refractory GPA

- •Outcomes and Prognostic Factors

- •Survival and Causes of Deaths

- •Relapse

- •Damage and Disease Burden on Quality of Life

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •9: Alveolar Hemorrhage

- •Introduction

- •Clinical Presentation

- •Diagnosis (Table 9.1, Fig. 9.3)

- •Pulmonary Capillaritis

- •Histology (Fig. 9.4)

- •Etiologies

- •ANCA-Associated Small Vessel Vasculitis: Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA)

- •ANCA-Associated Small Vessel Vasculitis: Microscopic Polyangiitis

- •Isolated Pulmonary Capillaritis

- •Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- •Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome

- •Anti-Basement Membrane Antibody Disease (Goodpasture Syndrome)

- •Lung Allograft Rejection

- •Others

- •Bland Pulmonary Hemorrhage (Fig. 9.5)

- •Histology

- •Etiologies

- •Idiopathic Pulmonary Hemosiderosis

- •Drugs and Medications

- •Coagulopathy

- •Valvular Heart Disease and Left Ventricular Dysfunction

- •Other

- •Histology

- •Etiologies

- •Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT)

- •Cocaine Inhalation

- •Acute Exacerbation of Interstitial Lung Disease

- •Acute Interstitial Pneumonia

- •Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- •Miscellaneous Causes

- •Etiologies

- •Pulmonary Capillary Hemangiomatosis

- •Treatment

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Takayasu Arteritis

- •Epidemiology

- •Pathologic Features

- •Pathogenesis

- •Clinical Features

- •Laboratory Findings

- •Imaging Studies

- •Therapeutic Management

- •Prognosis

- •Behçet’s Disease

- •Epidemiology

- •Pathologic Features

- •Pathogenesis

- •Diagnostic Criteria

- •Clinical Features

- •Pulmonary Artery Aneurysm

- •Pulmonary Artery Thrombosis

- •Pulmonary Parenchymal Involvement

- •Laboratory Findings

- •Imaging Studies

- •Therapeutic Management

- •Treatment of PAA

- •Treatment of PAT

- •Prognosis

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Portopulmonary Hypertension (PoPH)

- •Epidemiology and Risk Factors

- •Molecular Pathogenesis

- •PoPH Treatment

- •Hepatopulmonary Syndrome (HPS)

- •Epidemiology and Risk Factors

- •Molecular Pathogenesis

- •HPS Treatment

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •12: Systemic Sclerosis and the Lung

- •Introduction

- •Risk factors for SSc-ILD

- •Genetic Associations

- •Clinical Presentation of SSc-ILD

- •Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs)

- •Imaging

- •Management

- •References

- •13: Rheumatoid Arthritis and the Lungs

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology

- •Risk Factors for ILD (Table 13.3)

- •Pathogenesis

- •Clinical Features and Diagnosis

- •Treatments

- •Prognosis

- •Epidemiology

- •Risk Factors

- •Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Outcome

- •Subtypes or RA-AD

- •Obliterative Bronchiolitis

- •Bronchiectasis

- •COPD

- •Cricoarytenoid Involvement

- •Pleural Disease

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- •Epidemiology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Pulmonary Manifestations

- •Pleural Disease

- •Shrinking Lung Syndrome

- •Thrombotic Manifestations

- •Interstitial Lung Disease

- •Other Pulmonary Manifestations

- •Prognosis

- •Sjögren’s Syndrome

- •Epidemiology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Pulmonary Manifestations

- •Airway Disorders

- •Lymphoproliferative Disease

- •Interstitial Lung Disease

- •Prognosis

- •Mixed Connective Tissue Disease

- •Epidemiology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Pulmonary Manifestations

- •Pulmonary Hypertension

- •Interstitial Lung Disease

- •Prognosis

- •Myositis

- •Epidemiology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Pulmonary Manifestations and Treatments

- •Interstitial Lung Disease

- •Respiratory Muscle Weakness

- •Other Pulmonary Manifestations

- •Prognosis

- •Other Therapeutic Options in CTD-ILD

- •Lung Transplantation

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Diagnostic Criteria

- •Controversies in the Diagnostic Criteria

- •Typical Clinical Features

- •Disease Progression and Prognosis

- •Summary

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Histiocytes and Dendritic Cells

- •Introduction

- •Cellular and Molecular Pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Clinical Presentation

- •Treatment and Prognosis

- •Erdheim-Chester Disease

- •Epidemiology

- •Cellular and Molecular Pathogenesis

- •Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

- •Clinical Presentation

- •Investigation/Diagnosis

- •Chest Studies

- •Cardiovascular Imaging

- •CNS Imaging

- •Bone Radiography

- •Other Imaging Findings and Considerations

- •Disease Monitoring

- •Pathology

- •Management/Treatment

- •Prognosis

- •Rosai-Dorfman Destombes Disease

- •Epidemiology

- •Etiology/Pathophysiology

- •Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

- •Clinical Presentation

- •Investigation/Diagnosis

- •Management/Treatment

- •Prognosis

- •Conclusions

- •Diagnostic Criteria for Primary Histiocytic Disorders of the Lung

- •References

- •17: Eosinophilic Pneumonia

- •Introduction

- •Eosinophil Biology

- •Physiologic and Immunologic Role of Eosinophils

- •Release of Mediators

- •Targeting the Eosinophil Cell Lineage

- •Historical Perspective

- •Clinical Presentation

- •Pathology

- •Diagnosis

- •Eosinophilic Lung Disease of Undetermined Cause

- •Idiopathic Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia

- •Clinical Features

- •Imaging

- •Laboratory Studies

- •Bronchoalveolar Lavage

- •Lung Function Tests

- •Treatment

- •Outcome and Perspectives

- •Clinical Features

- •Imaging

- •Laboratory Studies

- •Bronchoalveolar Lavage

- •Lung Function Tests

- •Lung Biopsy

- •Treatment and Prognosis

- •Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis

- •History and Nomenclature

- •Pathology

- •Clinical Features

- •Imaging

- •Laboratory Studies

- •Pathogenesis

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment and Prognosis

- •Long-Term Outcome

- •Hypereosinophilic Syndrome

- •Pathogenesis

- •Clinical and Imaging Features

- •Laboratory Studies

- •Treatment and Prognosis

- •Eosinophilic Pneumonias of Parasitic Origin

- •Tropical Eosinophilia [191]

- •Ascaris Pneumonia

- •Eosinophilic Pneumonia in Larva Migrans Syndrome

- •Strongyloides Stercoralis Infection

- •Eosinophilic Pneumonias in Other Infections

- •Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis

- •Pathogenesis

- •Diagnostic Criteria

- •Biology

- •Imaging

- •Treatment

- •Bronchocentric Granulomatosis

- •Miscellaneous Lung Diseases with Associated Eosinophilia

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Pulmonary Langerhans’ Cell Histiocytosis

- •Epidemiology

- •Pathogenesis

- •Diagnosis

- •Clinical Features

- •Extrathoracic Lesions

- •Pulmonary Function Tests

- •Chest Radiography

- •High-Resolution Computed Tomography (HRCT)

- •Bronchoscopy and Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL)

- •Lung Biopsy

- •Pathology

- •Treatment

- •Course and Prognosis

- •Case Report I

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology

- •Clinical Features

- •Histopathological Findings

- •Radiologic Findings

- •Prognosis and Therapy

- •Desquamative Interstitial Pneumonia

- •Epidemiologic and Clinical Features

- •Histopathological Findings

- •Radiological Findings

- •Prognosis and Therapy

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •19: Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

- •Introduction

- •Pathogenesis

- •Presentation

- •Prognosis

- •Management

- •General Measures

- •Parenchymal Lung Disease

- •Pleural Disease

- •Renal Angiomyolipoma

- •Abdominopelvic Lymphatic Disease

- •Pregnancy

- •Tuberous Sclerosis

- •Drug Treatment

- •Bronchodilators

- •mTOR Inhibitors

- •Anti-Oestrogen Therapy

- •Experimental Therapies

- •Interventions for Advanced Disease

- •Oxygen Therapy

- •Pulmonary Hypertension

- •References

- •20: Diffuse Cystic Lung Disease

- •Introduction

- •Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

- •Pathogenesis

- •Pathologic and Radiographic Characteristics

- •Diagnostic Approach

- •Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (PLCH)

- •Pathogenesis

- •Pathological and Radiographic Characteristics

- •Diagnostic Approach

- •Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome (BHD)

- •Pathogenesis

- •Pathological and Radiographic Characteristics

- •Diagnostic Approach

- •Lymphoproliferative Disorders

- •Pathogenesis

- •Pathological and Radiographic Characteristics

- •Diagnostic Approach

- •Amyloidosis

- •Light Chain Deposition Disease (LCDD)

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Lymphatic Development

- •Clinical Presentation of Lymphatic Disorders

- •Approaches to Diagnosis and Management of Congenital Lymphatic Anomalies

- •Generalized Lymphatic Anomaly

- •Etiopathogenesis

- •Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

- •Course/Prognosis

- •Management

- •Kaposiform Lymphangiomatosis

- •Etiopathogenesis

- •Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

- •Management

- •Course/Prognosis

- •Gorham Stout Disease

- •Etiopathogenesis

- •Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

- •Management

- •Course/Prognosis

- •Channel-Type LM/Central Conducting LM

- •Etiopathogenesis

- •Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

- •Management

- •Course/Prognosis

- •Yellow Nail Syndrome

- •Etiopathogenesis

- •Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

- •Management

- •Course/Prognosis

- •Summary

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Historical Note

- •Epidemiology

- •Pathogenesis

- •Surfactant Homeostasis in PAP

- •GM-CSF Signaling Disruption

- •Myeloid Cell Dysfunction

- •GM-CSF Autoantibodies

- •Lymphocytosis

- •Clinical Manifestations

- •Clinical Presentation

- •Secondary Infections

- •Pulmonary Fibrosis

- •Diagnosis

- •Pulmonary Function Testing

- •Radiographic Assessment

- •Bronchoscopy and Bronchoalveolar Lavage

- •Laboratory Studies and Biomarkers

- •GM-CSF Autoantibodies

- •Genetic Testing

- •Lung Pathology

- •Diagnostic Approach to the Patient with PAP

- •Natural History and Prognosis

- •Treatment

- •Whole-Lung Lavage

- •Subcutaneous GM-CSF

- •Inhaled GM-CSF

- •Other Approaches

- •Conclusions and Future Directions

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology

- •Gastric Contents

- •Pathobiology of GER/Microaspirate in the Lungs of Patients with IPF

- •GER and the Microbiome

- •Diagnosis

- •Clinical History/Physical Exam

- •Investigations

- •Esophageal Physiology

- •Upper Esophageal Sphincter

- •Esophagus and Peristalsis

- •Lower Esophageal Sphincter and Diaphragm

- •Esophageal pH and Impedance Testing

- •High Resolution Esophageal Manometry

- •Esophagram/Barium Swallow

- •Bronchoalveolar Lavage/Sputum: Biomarkers

- •Treatment

- •Anti-Acid Therapy (PPI/H2 Blocker)

- •GER and Acute Exacerbations of IPF

- •Suggested Approach

- •Summary and Future Directions

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Familial Interstitial Pneumonia

- •Telomere Related Genes

- •Genetic

- •Telomere Length

- •Pulmonary Involvement

- •Interstitial Lung Disease

- •Other Lung Disease

- •Hepatopulmonary Syndrome

- •Emphysema

- •Extrapulmonary Manifestations

- •Mucocutaneous Involvement

- •Hematological Involvement

- •Liver Involvement

- •Other Manifestations

- •Treatment

- •Telomerase Complex Agonists

- •Lung Transplantation

- •Surfactant Pathway

- •Surfactant Protein Genes

- •Pulmonary Involvement

- •Treatment

- •Heritable Forms of Pulmonary Fibrosis with Autoimmune Features

- •TMEM173

- •COPA

- •Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis

- •GMCSF Receptor Mutations

- •GATA2

- •MARS

- •Lysinuric Protein Intolerance

- •Lysosomal Diseases

- •Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome

- •Lysosomal Storage Disorders

- •FAM111B, NDUFAF6, PEPD

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical Presentation

- •Epidemiology

- •Genetic Causes of Bronchiectasis

- •Disorders of Mucociliary Clearance

- •Cystic Fibrosis

- •Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

- •Other Ciliopathies

- •X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia

- •Chronic Granulomatous Disease and Other Disorders of Neutrophil Function

- •Other Genetic Disorders Predisposing to Bronchiectasis

- •Idiopathic Bronchiectasis

- •Diagnosis of Bronchiectasis

- •Management of Patients with Bronchiectasis

- •Airway Clearance Therapy (ACT)

- •Management of Infections

- •Immune Therapy

- •Surgery

- •Novel Therapies for Managing Cystic Fibrosis

- •Summary

- •References

- •Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations

- •Background Pulmonary AVMs

- •Anatomy Pulmonary AVMs

- •Clinical Presentation of Pulmonary AVMs

- •Screening Pulmonary AVMs

- •Treatment Pulmonary AVMs

- •Children with Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia

- •Pulmonary Hypertension

- •Pulmonary Hypertension Secondary to Liver Vascular Malformations

- •Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension

- •Background HHT

- •Pathogenesis

- •References

- •27: Pulmonary Alveolar Microlithiasis

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology

- •Pathogenesis

- •Clinical Features

- •Diagnosis

- •Management

- •Summary

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome

- •Telomerase-Associated Pulmonary Fibrosis

- •Lysosomal Storage Diseases

- •Lysinuric Protein Intolerance

- •Familial Hypocalciuric Hypercalcemia

- •Surfactant Dysfunction Disorders

- •Concluding Remarks

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Background

- •Image Acquisition

- •Key Features of Fibrosis

- •Ancillary Features of Fibrosis

- •Other Imaging Findings in FLD

- •Probable UIP-IPF

- •Indeterminate

- •Alternative Diagnosis

- •UIP in Other Fibrosing Lung Diseases

- •Pleuroparenchymal Fibroelastosis (PPFE)

- •Combined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema

- •Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

- •Other Fibrosing Lung Diseases

- •Fibrosing Sarcoidosis

- •CTD-ILD and Drug-Induced FLD

- •Complications

- •Prognosis

- •Computer Analysis of CT Imaging

- •The Progressive Fibrotic Phenotype

- •Other Imaging Techniques

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL)

- •Technique

- •Interpretation

- •Transbronchial Biopsy (TBB)

- •Transbronchial Lung Cryobiopsy (TLCB)

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Overview of ILD Diagnosis

- •Clinical Assessment

- •Radiological Assessment

- •Laboratory Assessment

- •Integration of Individual Features

- •Multidisciplinary Discussion

- •Diagnostic Ontology

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

- •Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

- •Connective Tissue Disease

- •Drug-Induced Lung Diseases

- •Radiation Pneumonitis

- •Asbestosis

- •Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome

- •Risk Factors for Progression

- •Diagnosis

- •Pharmacological Management

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Historical Perspective

- •Epidemiology and Etiologies

- •Tobacco Smoking and Male Sex

- •Genetic Predisposition

- •Systemic Diseases

- •Other Etiological Contexts

- •Clinical Manifestations

- •Pulmonary Function and Physiology

- •Imaging

- •Computed Tomography Characteristics and Patterns

- •Thick-Walled Large Cysts

- •Imaging Phenotypes

- •Pitfalls

- •Pathology

- •Diagnosis

- •CPFE Is a Syndrome

- •Biology

- •Complications and Outcome

- •Mortality

- •Pulmonary Hypertension

- •Lung Cancer

- •Acute Exacerbation of Pulmonary Fibrosis

- •Other Comorbidities and Complications

- •Management

- •General Measures and Treatment of Emphysema

- •Treatment of Pulmonary Fibrosis

- •Management of Pulmonary Hypertension

- •References

- •Acute Interstitial Pneumonia (AIP)

- •Epidemiology

- •Presentation

- •Diagnostic Evaluation

- •Radiology

- •Histopathology

- •Clinical Course

- •Treatment

- •Epidemiology

- •Presentation

- •Diagnostic Evaluation

- •Radiology

- •Histopathology

- •Clinical Course

- •Desquamative Interstitial Pneumonia (DIP)

- •Presentation

- •Diagnostic Evaluation

- •Radiology

- •Histopathology

- •Clinical Course

- •Treatment

- •Epidemiology

- •Presentation

- •Diagnostic Evaluation

- •Radiology

- •Histopathology

- •Clinical Course

- •Treatment

- •References

- •Organizing Pneumonias

- •Epidemiology

- •Pathogenesis

- •Clinical Features

- •Imaging

- •Multifocal Form

- •Isolated Nodular Form

- •Other Imaging Patterns

- •Histopathological Diagnosis of OP Pattern

- •Etiological Diagnosis of OP

- •Treatment

- •Clinical Course and Outcome

- •Severe Forms of OP with Respiratory Failure

- •Acute Fibrinous and Organizing Pneumonia

- •Granulomatous Organizing Pneumonia

- •Acute Interstitial Pneumonia

- •Epidemiology

- •Clinical Picture

- •Imaging

- •Histopathology

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Outcome

- •References

- •36: Pleuroparenchymal Fibroelastosis

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology

- •Clinical Manifestations

- •Laboratory Findings

- •Respiratory Function

- •Radiologic Features

- •Pathologic Features

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Prognosis

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Acute Berylliosis

- •Chronic Beryllium Disease

- •Exposure

- •Epidemiology

- •Immunopathogenesis and Pathology

- •Genetics

- •Clinical Description and Natural History

- •Treatment and Monitoring

- •Indium–Tin Oxide-Lung Disease

- •Hard Metal Lung

- •Flock Worker’s Disease

- •Asbestosis

- •Nanoparticle Induced ILD

- •Flavoring-Induced Lung Disease

- •Silica-Induced Interstitial Lung Disease

- •Chronic Silicosis

- •Acute and Accelerated Silicosis

- •Chronic Obstructive Disease in CMDLD

- •Simple CMDLD

- •Complicated CMDLD

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •38: Unclassifiable Interstitial Lung Disease

- •Introduction

- •Diagnostic Scenarios

- •Epidemiology

- •Clinical Presentation

- •Diagnosis

- •Clinical Features

- •Radiology

- •Laboratory Investigations

- •Pathology

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •39: Lymphoproliferative Lung Disorders

- •Introduction

- •Nodular Lymphoid Hyperplasia

- •Lymphocytic Interstitial Pneumonia (LIP)

- •Follicular Bronchitis/Bronchiolitis

- •Castleman Disease

- •Primary Pulmonary Lymphomas

- •Primary Pulmonary MALT B Cell Lymphoma

- •Pulmonary Plasmacytoma

- •Follicular Lymphoma

- •Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis

- •Primary Pulmonary Hodgkin Lymphoma (PPHL)

- •Treatment

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Late-Onset Pulmonary Complications

- •Bronchiolitis Obliterans (BO)

- •Pathophysiology

- •Diagnosis

- •Management of BOS

- •Post-HSCT Organizing Pneumonia

- •Other Late-Onset NonInfectious Pulmonary Complications (LONIPCs)

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Pulmonary Hypertension Associated with Sarcoidosis (Group 5.2)

- •PH Associated with Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (Group 5.2)

- •PH in Combined Pulmonary Fibrosis and Emphysema (Group 3.3)

- •PH Associated with Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (Group 3)

- •Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (Group 1.2)

- •Pulmonary Veno-Occlusive Disease (Group 1.5)

- •Small Patella Syndrome (Group 1.2)

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology

- •Timing, Chronology, Delay Time

- •Route of Administration

- •Patterns of Involvement [3, 4]

- •Drugs and Agents Fallen Out of Favor

- •Drug-Induced Noncardiac Pulmonary Edema

- •Drug-Induced Cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema

- •The “Chemotherapy Lung”

- •Drug-Induced/Iatrogenic Alveolar Hemorrhage

- •Drugs

- •Superwarfarin Rodenticides

- •Transfusion Reactions: TACO–TRALI

- •Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia

- •Acute Granulomatous Interstitial Lung Disease

- •Acute Organizing Pneumonia (OP), Bronchiolitis Obliterans Organizing Pneumonia (BOOP), or Acute Fibrinous Organizing Pneumonia (AFOP) Patterns

- •Acute Amiodarone-Induced Pulmonary Toxicity (AIPT)

- •Accelerated Pulmonary Fibrosis

- •Acute Exacerbation of Previously Known (Idiopathic) Pulmonary Fibrosis

- •Anaphylaxis

- •Acute Vasculopathy

- •Drug-Induced/Iatrogenic Airway Emergencies

- •Airway Obstruction as a Manifestation of Anaphylaxis

- •Drug-Induced Angioedema

- •Hematoma Around the Upper Airway

- •The “Pill Aspiration Syndrome”

- •Catastrophic Drug-Induced Bronchospasm

- •Peri-operative Emergencies (Table 42.8)

- •Other Rare Presentations

- •Pulmonary Nodules and Masses

- •Pleuroparenchymal Fibroelastosis

- •Late Radiation-Induced Injury

- •Chest Pain

- •Rebound Phenomenon

- •Recall Pneumonitis

- •Thoracic Bezoars: Gossipybomas

- •Respiratory Diseases Considered Idiopathic That May Be Drug-Induced (Table 42.4)

- •Eye Catchers

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Cancer Mimics of Organizing Pneumonia

- •Lung Adenocarcinoma/Bronchioloalveolar Carcinoma

- •Primary Pulmonary Lymphoma

- •Cancer Mimics of Interstitial Lung Diseases

- •Lymphangitic Carcinomatosis

- •Epithelioid Hemangio-Endothelioma

- •Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis

- •Cystic Tumors

- •Cavitating Tumors

- •Intrathoracic Pseudotumors

- •Respiratory Papillomatosis

- •Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis

- •References

- •Index

Unclassifiable Interstitial Lung Disease |

38 |

|

|

Sabina A. Guler and Christopher J. Ryerson |

|

Clinical Vignette

A previously healthy 68-year-old man presented with a 1-year history of gradually worsening dyspnoea and fatigue. A chest X-ray had demonstrated bilateral basilar abnormalities, and he was treated with moxi oxacin by his family physician with no improvement. The patient had a history of gastroesophageal re ux for which he was on a proton pump inhibitor. He was on no other medication. He had quit smoking ten years earlier after a 30-pack-year smoking history. He reported no symptoms suggestive of connective tissue disease (CTD), no environmental or occupational exposures, and no remarkable family history.

His oxygen saturation was 93% while breathing room air, and decreased to 89% during a 6-min walk test. Physical examination revealed bilateral basal coarse crackles, no digital clubbing, and no signs of connective tissue disease or heart failure. Lung function tests included a forced vital capacity of 81%-pre- dicted and diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide of 64%-predicted. Blood tests revealed a borderline increased creatinine kinase and C-reactive peptide. Autoimmune serologies included a mildly abnormal anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide and SSA

S. A. Guler (*)

Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Inselspital, University Hospital Bern, Bern, Switzerland

e-mail: sabina.guler@insel.ch

C. J. Ryerson

Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Centre for Heart Lung Innovation, St. Paul’s Hospital, Vancouver, BC, Canada

St. Paul’s Hospital, Vancouver, BC, Canada e-mail: chris.ryerson@hli.ubc.ca

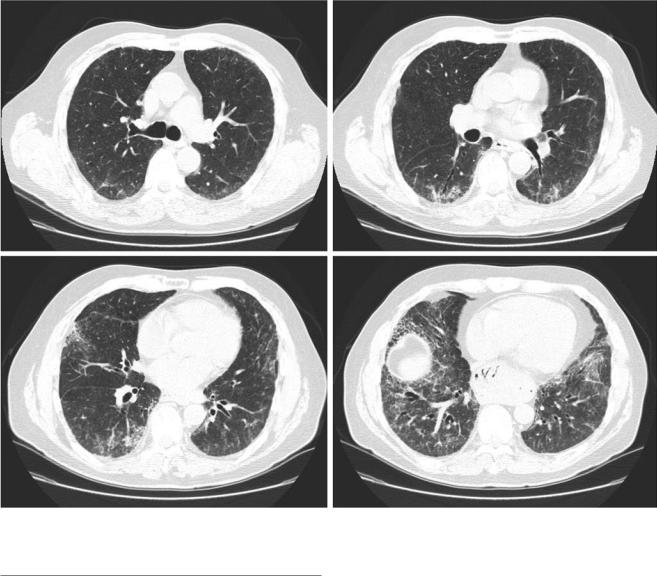

antibody. Serum precipitins were negative. Chest CT demonstrated lower-lung predominant reticulation, traction bronchiectasis, and some superimposed ground glass with a pattern most suggestive of nonspecifc interstitial pneumonia (Fig. 38.1. A surgical lung biopsy showed features of usual interstitial pneumonia, but with increased numbers of interstitial lymphocytes and both interstitial and airspace giant cells, beyond what would be expected in idiopathic pulmonary fbrosis.

A comprehensive assessment by a rheumatologist concluded there was no evidence of a connective tissue disease. Multidisciplinary discussion concluded an unclear aetiology of the ILD, with a differential diagnosis that included hypersensitivity pneumonitis, connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease, and less likely idiopathic pulmonary fbrosis. The patient was treated with immunosuppressive medications based on the more likely differential diagnoses of hypersensitivity pneumonitis and connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. He had initial stabilization in his symptoms and lung function, but eventually had progression of his disease and passed away 6 years after initial presentation.

© Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2023 |

671 |

V. Cottin et al. (eds.), Orphan Lung Diseases, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12950-6_38 |

|

672 |

S. A. Guler and C. J. Ryerson |

|

|

Fig. 38.1 Clinical vignette. Selected axial images from a high-resolution CT showing lower-lung predominant reticulation, traction bronchiectasis, and superimposed ground glass

Introduction

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a group of typically rare disorders that are distinct enough to be regarded as separate disease entities. ILDs damage the lung parenchyma in varying degrees of in ammation and fbrosis, with some having a known underlying cause and others where no cause can be identifed [1]. The most common of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIP) is idiopathic pulmonary fbrosis (IPF). Other common ILDs include fbrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), and connective tissue disease-associated ILD (CTDILD). Patients with ILD usually present with nonspecifc respiratory symptoms such as progressive dyspnoea and cough. The classifcation into a specifc ILD subtype can be challenging because the clinical, radiological, and pathological fndings frequently overlap. Accurate ILD classifcation informs prevention, management, and prognosis: Associated

exposures need to be eliminated, the indicated pharmacotherapy differs between ILD subtypes, and prognosis varies vastly. Most importantly, immunosuppressive therapy is frequently recommended for patients with CTD-ILD, [2, 3] whereas patients with IPF are potentially harmed by immunosuppression and are instead treated with antifbrotic medications [4– 6]. Despite its importance, the classifcation of an ILD cannot always be achieved. Even with a thorough investigation for potential aetiologies or features that allow the categorization of the ILD, a subset of ILD patients cannot be provided with a specifc ILD diagnosis and remain unclassifable [7].

The classifcation of the IIPs has evolved substantially since the frst classifcation by the pathologist Averill Abraham Liebow in 1968 [8]. In 2002, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) provided the frst standardized nomenclature and set of diagnostic criteria for the major IIPs [9]. The

Данная книга находится в списке для перевода на русский язык сайта https://meduniver.com/

38 Unclassifable Interstitial Lung Disease |

673 |

|

|

authors of this consensus paper acknowledged the diagnostic dilemma of unclassifable ILD with a subset of IIP patients that are not classifable even after a thorough clinical, radiological, and pathological investigations. Mainly based on lack of clinical utility, it was decided against creating an unclassifable ILD category at that time. The updated IIP classifcation consensus statement in 2013 introduced the category of unclassifable ILD, with the caution that the use of the label unclassifable ILD should not be used to justify avoidance of a thorough diagnostic process [1]. Over the last few years multiple cohort studies have described this heterogeneous population, tools to phenotype patients with unclassifable ILD are emerging, and clinical trials investigating pharmacotherapies are ongoing.

In this chapter we address the clinical picture of unclassifable ILD and discuss challenges and potential solutions for the management of these patients.

Defnition

Unclassifable, unclassifed, undefned, and undetermined ILD are terms that have been used to label the group of ILD patients that cannot be provided with a specifc, defned ILD [7]. There are no diagnostic criteria for unclassifable ILD,

and there is no universally accepted defnition of the term. The most consistently used defnition is the absence of a clear diagnosis following a multidisciplinary discussion that includes review of all available clinical, radiological, and pathological information [7, 10, 11]. Some clinicians and researchers have advocated to reserve the term unclassifable ILD to patients where a multidisciplinary team has reviewed results from a complete diagnostic workup including SLB, before calling a case unclassifable. In contrast, cases without a complete evaluation would be called unclassifed ILD. Unclassifed then indicates the possibility of classifying the ILD case later when new information becomes available (e.g., when a patient undergoes SLB) [10, 12]. Notably, patients with unclassifable ILD despite a SLB could similarly still be provided a diagnosis eventually following discovery of new information (e.g., a new diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis), indicating that the term “unclassifable” is also a temporary designation in some patients.

A more standardized approach to the defnition of unclassifable ILD was proposed in an ontological framework for fbrotic ILD: A confdent diagnosis is defned by having ≥90% diagnostic confdence, a provisional diagnosis by 51–89% confdence, and unclassifable ILD by the absence of a single diagnosis that is more likely than not (i.e., <51% confdence; Fig. 38.2) [13]. Using this approach, it is also

Patient presenting with fibrotic interstitial lung disease

Is there a leading diagnosis that meets guideline criteria or has ≥90% confidence?

No

Is there a leading diagnosis that has >50% confidence?

No

Yes |

Confident diagnosis |

|

|

“Provlslonal” diagnosis |

|

Yes |

High confidence diagnosis |

|

(70–89% confidence) |

||

|

||

|

Low confidence diagnosis |

|

|

(51–69% confidence) |

|

|

“Unclasslflable ILD” |

Document differential diagnosis

Fig. 38.2 Proposed approach to the classifcation of fbrotic interstitial lung disease (ILD). (Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2019 American Thoracic Society. Ryerson CJ, Corte TJ, Lee JS, Richeldi L, Walsh SLF, Myers JL, Behr J, Cottin V, Danoff SK, Flaherty KR, Lederer DJ, Lynch DA, Martinez FJ, Raghu G, Travis WD, Udwadia Z, Wells AU, Collard HR. /2017/ A

Standardized Diagnostic Ontology for Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease: An International Working Group Perspective/American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine/196/1249–1254. The

American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine is an offcial journal of the American Thoracic Society)