- •Unit 1 history of computer engineering

- •Vocabulary

- •Match the words with their definitions:

- •Watching

- •Find and learn Russian equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •Find and learn English equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •3. Create a word finder for any 20 computer terms using the following website:

- •Look at these sentences from the article, underline and name the Passive forms:

- •Find and underline other examples in the text.

- •Find the mistakes and correct the sentence.

- •Make up another sentence with the same meaning using passive structures.

- •Translate the following sentences into Russian.

- •Translate the following sentences into English.

- •10. Answer the following questions.

- •What the first computer originally was?

- •Unit 2

- •Information is a fundamental property of the world around

- •Vocabulary

- •Match the words with their definitions:

- •Watching

- •Now watch a video ‘What is information?’ and mark True (t) or False (f).

- •1. Discuss with your partner the following questions.

- •Skim the text to check your ideas.

- •What is information?

- •Find and learn Russian equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •Find and learn English equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •Information

- •Find and underline other examples in the text.

- •Find the mistakes and correct the sentence.

- •Use the prompts to make conditional sentences.

- •Translate the following sentences into Russian.

- •Translate the following sentences into English.

- •Answer the following questions.

- •Topics for discussion.

- •Prepare a presentation on the topic being discussed.

- •Unit 3

- •Vocabulary measuring amount of information

- •Match the words with their definitions:

- •Watching

- •Nasa Kids Science News segment explains the difference between bits and bytes. Now watch a video ‘What’s the difference between bits and bytes?’ and mark True (t) or False (f).

- •Discuss with your partner the following question.

- •Skim the text to check your ideas.

- •How bits & bytes work

- •Find and learn Russian equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •Find and learn English equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •Find and underline other examples of participles in the text.

- •Underline the correct item.

- •Find the mistakes and correct the sentence.

- •Translate the following sentences into Russian.

- •Translate the following sentences into English.

- •Answer the following questions.

- •Topics for discussion.

- •Prepare a presentation on the topic being discussed.

- •Standard ascii Character Set

- •Unit 4

- •Vocabulary microsoft office

- •Match the words with their definitions:

- •Watching

- •Before you read

- •Discuss with your partner the following question.

- •Skim the text to check your ideas. Reading microsoft software suit

- •Find and learn Russian equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •Find and learn English equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •Find and learn the definitions for the following abbreviations.

- •Find the example of this structure in the text and translate the sentence.

- •Complete the following sentences with the right preposition.

- •Translate the following sentences into Russian.

- •Translate the following sentences into English.

- •Answer the following questions.

- •Topics for discussion.

- •References, useful links and further reading References and further reading Prepare a presentation on the topic being discussed.

- •Unit 1 (12)

- •Vocabulary computation

- •Match the words with their definitions:

- •Discuss with your partner the following questions.

- •Skim the text to check your ideas.

- •Algorithms

- •Find and learn Russian equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •Find and learn English equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •Insertion sort

- •Translate the following sentences into Russian.

- •Translate the following sentences into English.

- •Answer the following questions.

- •Paragraph

- •The sentences below make up a paragraph, but have been mixed up. Use the table to re-write the sentences in the correct order.

- •You are writing an essay on ‘Algorithms’. Using the notes below, complete the introductory paragraph, following the structure provided.

- •Introduction

- •What is the purpose of the introduction to an essay? Choose from the items below:

- •Write an introduction (about 100 words) to an essay on a subject from your own discipline.

- •Organising the Main Body

- •Complete with suitable phrases the following extract from an essay on ‘Data structure’.

- •Write the main body (about 100 words) to an essay on a subject from your own discipline.

- •Conclusion

- •The following may be found in conclusions. Decide on the most suitable order for them (1-5).

- •Read the following extracts from the conclusion and match them with the list of functions in the box. Decide on the most suitable order for them.

- •Write a conclusion (about 100 words) to an essay on a subject from your own discipline.

- •Unit 2 (13) computer modelling

- •Vocabulary

- •Match the words with their definitions:

- •Discuss with your partner the following questions.

- •Skim the text to check your ideas.

- •The computer modeling process

- •Find and learn Russian equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •Find and learn English equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •Virtual Reality

- •Translate the following sentences into Russian.

- •Translate the following sentences into English.

- •Answer the following questions.

- •Prepare a presentation on the topic being discussed.

- •Elements of writing (1)

- •Complete the following sentences with a suitable verb or conjunction.

- •Write three more sentences from your own subject area.

- •Cohesion

- •Read the following paragraph and complete the table.

- •Definitions

- •Insert suitable category words in the following definitions.

- •Complete and extend the following definitions.

- •Discussion

- •Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of simulation Simulation Pros and Cons

- •Study the example and write similar sentences about simulation using ideas from (7).

- •Examples

- •Use suitable example phrases to complete the following sentences.

- •Generalisations

- •Write generalisations on the following topics.

- •Unit 3 (14) programming languages & paradigms

- •Vocabulary

- •Match the words with their definitions:

- •Discuss with your partner the following questions.

- •Is there any difference? Which one if any?

- •Skim the text to check your ideas.

- •What is what?

- •Find and learn Russian equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •Find and learn English equivalents for the following words and expressions:

- •Imperative paradigm

- •Translate the following sentences into Russian.

- •Translate the following sentences into English.

- •Answer the following questions.

- •Prepare a presentation on the topic being discussed.

- •Elements of writing (2)

- •Only Four People Showed Up to Protest Apple at Grand Central

- •2. Rewrite each sentence in a simpler way, using one of the expressions above.

- •3. Write a summary of the author’s ideas, including a suitable reference.

- •In the following, first underline the examples of poor style and then re-write them in a more suitable way:

- •Replace all the words or phrases in italic with suitable synonyms.

- •Below are illustrations of some of the main types of visuals used in academic texts. Match the uses (a-f) to the types (1-6) and the examples (a-f) in the box below.

- •Place the correct letter in the right box.

CONTENTS

Unit 1 |

History of computer engineering: Hardware History Overview |

|

Unit 2 |

Information Is A Fundamental Property Of The World Around: What Is Information? |

|

Unit 3 |

Measuring Amount Of Information: How Bits & Bytes Work |

|

Unit 4 |

Microsoft Office: Microsoft Software Suit |

|

Unit 5 |

|

|

Unit 1 history of computer engineering

Vocabulary

Match the words with their definitions:

1) cipher (n.) also cypher |

['saɪfə] |

a) present, appearing, or found everywhere |

2) non-volatile (adj.) |

[nɔn'vɔlətaɪl] |

b) a tube with a nozzle and piston or bulb for sucking in and ejecting liquid in a thin stream |

3) inefficient (adj.) |

[ˌɪnɪ'fɪʃ(ə)nt] |

c) taking up much space, typically inconveniently; large and unwieldy |

4) bulky (adj.) |

['bʌlkɪ] |

d) an annual calendar containing important dates and statistical information such as astronomical data and tide tables |

5) domain (n.) |

[dəu'meɪn] |

e) a table or device designed to assist with calculation |

6) almanac (n.) |

['ɔːlmənæk] |

f) not achieving maximum productivity; wasting or failing to make the best use of time or resources |

7) abacus (n.) |

['abəkəs] |

g) unreasonably high |

8) operand (n.) |

['ɔpər(ə)nd] |

h) retaining data even if there is a break in the power supply |

9) exorbitant (adj.) |

[ɪg'zɔːbɪt(ə)nt] |

i) a simple device for calculating, consisting of a frame with rows of wires or grooves along which beads are slid |

10) syringe (n.) |

[sɪ'rɪnʤ] |

j) write-protected |

11) reckoner (n.) |

['rek(ə)nə] |

k) an area of territory owned or controlled by a ruler or government |

12) read-only (adj.) |

[ri:dəunli] |

l) the quantity on which an operation is to be done |

13) ubiquitous (adj.) |

[juː'bɪkwɪtəs |

m) a secret or disguised way of writing; a code |

Watching

1. Now watch a video ‘Computer history in 140 seconds’ and say what computer is.

BEFORE

YOU READ

1. Discuss with your partner the following questions.

What do you know about the computers?

What are the reasons for inventing things?

READING

HARDWARE HISTORY OVERVIEW

The first computers were people! That is, electronic computers (and the earlier mechanical computers) were given this name because they performed the work that had previously been assigned to people. "Computer" was originally a job title: it was used to describe those human beings (predominantly women) whose job it was to perform the repetitive calculations required to compute such things as navigational tables, tide charts, and planetary positions for astronomical almanacs. Imagine you had a job where hour after hour, day after day, you were to do nothing but compute multiplications. Boredom would quickly set in, leading to carelessness, leading to mistakes. And even on your best days you wouldn't be producing answers very fast. Therefore, inventors have been searching for hundreds of years for a way to mechanize (that is, find a mechanism that can perform) this task [John Kopplin © 2002].

The

abacus

was an early aid for mathematical computations. Its only value is

that it aids the memory of the human performing the calculation. A

skilled abacus operator can work on addition and subtraction problems

at the speed of a person equipped with a hand calculator

(multiplication and division are slower). The abacus is often wrongly

attributed to China. In fact, the oldest surviving abacus was used in

300 B.C. by the Babylonians.

The

abacus

was an early aid for mathematical computations. Its only value is

that it aids the memory of the human performing the calculation. A

skilled abacus operator can work on addition and subtraction problems

at the speed of a person equipped with a hand calculator

(multiplication and division are slower). The abacus is often wrongly

attributed to China. In fact, the oldest surviving abacus was used in

300 B.C. by the Babylonians.

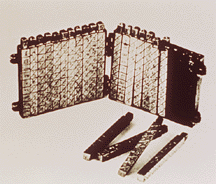

I

n

1617 an eccentric Scotsman named John Napier invented logarithms,

which are a technology that allows multiplication to be performed via

addition. The magic ingredient is the logarithm of each operand,

which was originally obtained from a printed table. But Napier also

invented an alternative to tables, where the logarithm values were

carved on ivory sticks which are now called Napier's

Bones.

n

1617 an eccentric Scotsman named John Napier invented logarithms,

which are a technology that allows multiplication to be performed via

addition. The magic ingredient is the logarithm of each operand,

which was originally obtained from a printed table. But Napier also

invented an alternative to tables, where the logarithm values were

carved on ivory sticks which are now called Napier's

Bones.

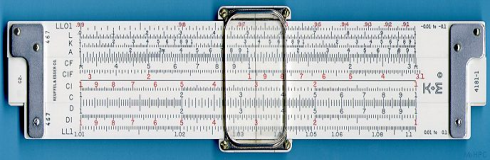

Napier's invention led directly to the slide rule, first built in England in 1632 and still in use in the 1960's by the NASA engineers of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs which landed men on the moon.

L eonardo

da Vinci (1452-1519) made drawings of gear-driven calculating

machines but apparently never built any.

eonardo

da Vinci (1452-1519) made drawings of gear-driven calculating

machines but apparently never built any.

T he

first gear-driven calculating machine to actually be built was

probably the calculating

clock,

so named by its inventor, the German professor Wilhelm Schickard in

1623. This device got little publicity because Schickard died soon

afterward in the bubonic plague.

he

first gear-driven calculating machine to actually be built was

probably the calculating

clock,

so named by its inventor, the German professor Wilhelm Schickard in

1623. This device got little publicity because Schickard died soon

afterward in the bubonic plague.

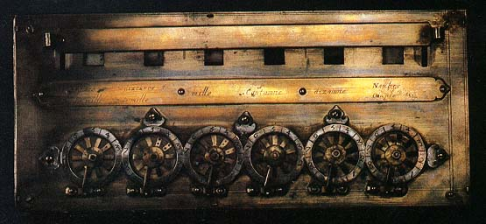

I n

1642 Blaise Pascal, at age 19, invented the Pascaline

as an aid for his father who was a tax collector. Pascal built 50 of

this gear-driven one-function calculator (it could only add) but

couldn't sell many because of their exorbitant

cost and because they really weren't that accurate (at that time it

was not possible to fabricate gears with the required precision). Up

until the present age when car dashboards went digital, the odometer

portion of a car's speedometer used t

n

1642 Blaise Pascal, at age 19, invented the Pascaline

as an aid for his father who was a tax collector. Pascal built 50 of

this gear-driven one-function calculator (it could only add) but

couldn't sell many because of their exorbitant

cost and because they really weren't that accurate (at that time it

was not possible to fabricate gears with the required precision). Up

until the present age when car dashboards went digital, the odometer

portion of a car's speedometer used t he

very same mechanism as the Pascaline to increment

the next wheel after each full revolution of the prior wheel. Pascal

was a child

prodigy.

At the age of 12, he was discovered doing his version of Euclid's

thirty-second proposition on the kitchen floor. Pascal went on to

invent probability theory, the hydraulic press, and the syringe.

he

very same mechanism as the Pascaline to increment

the next wheel after each full revolution of the prior wheel. Pascal

was a child

prodigy.

At the age of 12, he was discovered doing his version of Euclid's

thirty-second proposition on the kitchen floor. Pascal went on to

invent probability theory, the hydraulic press, and the syringe.

Just a few years after Pascal, the German Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (co-inventor with Newton of calculus) managed to build a four-function (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division) calculator that he called the stepped reckoner because, instead of gears, it employed fluted drums having ten flutes arranged around their circumference in a stair-step fashion. Although the stepped reckoner employed the decimal number system (each drum had 10 flutes), Leibniz was the first to advocate use of the binary number system which is fundamental to the operation of modern computers. Leibniz is considered one of the greatest of the philosophers but he died poor and alone.

I

n

1801 the Frenchman Joseph Marie Jacquard invented a power loom

that could base its weave (and hence the design on the fabric) upon a

pattern automatically read from punched wooden cards, held together

in a long row by rope. Descendents

of these punched

cards

have been in use ever since (remember the "hanging chad"

from the Florida presidential ballots of the year 2000).

n

1801 the Frenchman Joseph Marie Jacquard invented a power loom

that could base its weave (and hence the design on the fabric) upon a

pattern automatically read from punched wooden cards, held together

in a long row by rope. Descendents

of these punched

cards

have been in use ever since (remember the "hanging chad"

from the Florida presidential ballots of the year 2000).

Jacquard's technology was a real boon (benefit) to mill owners, but put many loom operators out of work. Angry mobs smashed Jacquard looms and once attacked Jacquard himself. History is full of examples of labor unrest following technological innovation yet most studies show that, overall, technology has actually increased the number of jobs.

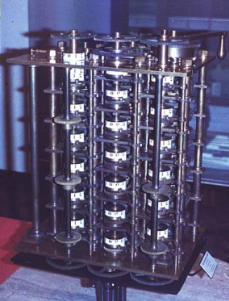

B y

1822 the English mathematician Charles

Babbage

was proposing a steam driven calculating machine the size of a room,

which he called the Difference

Engine.

This machine would be able to compute tables of numbers, such as

logarithm tables. He obtained government funding for this project due

to the importance of numeric tables in ocean navigation. By promoting

their commercial and military navies, the British government had

managed to become the earth's greatest empire. But in that time frame

the British government was publishing a seven volume set of

navigation tables which came with a companion volume of corrections

which showed that the set had over 1000 numerical errors. It was

hoped that Babbage's machine could eliminate errors in these types of

tables. But construction of Babbage's Difference Engine proved

exceedingly difficult and the project soon became the most expensive

government funded project up to that point in English history. Ten

years later the device was still nowhere near complete, acrimony

abounded between all involved, and funding dried up. The device was

never finished.

y

1822 the English mathematician Charles

Babbage

was proposing a steam driven calculating machine the size of a room,

which he called the Difference

Engine.

This machine would be able to compute tables of numbers, such as

logarithm tables. He obtained government funding for this project due

to the importance of numeric tables in ocean navigation. By promoting

their commercial and military navies, the British government had

managed to become the earth's greatest empire. But in that time frame

the British government was publishing a seven volume set of

navigation tables which came with a companion volume of corrections

which showed that the set had over 1000 numerical errors. It was

hoped that Babbage's machine could eliminate errors in these types of

tables. But construction of Babbage's Difference Engine proved

exceedingly difficult and the project soon became the most expensive

government funded project up to that point in English history. Ten

years later the device was still nowhere near complete, acrimony

abounded between all involved, and funding dried up. The device was

never finished.

Babbage was not deterred, and by then was on to his next brainstorm, which he called the Analytic Engine. This device, large as a house and powered by 6 steam engines, would be more general purpose in nature because it would be programmable, thanks to the punched card technology of Jacquard. But it was Babbage who made an important intellectual leap regarding the punched cards. In the Jacquard loom, the presence or absence of each hole in the card physically allows a colored thread to pass or stops that thread. Babbage saw that the pattern of holes could be used to represent an abstract idea such as a problem statement or the raw data required for that problem's solution. Furthermore, Babbage realized that punched paper could be employed as a storage mechanism, holding computed numbers for future reference. Because of the connection to the Jacquard loom, Babbage called the two main parts of his Analytic Engine the "Store" and the "Mill", as both terms are used in the weaving industry. The Store was where numbers were held and the Mill was where they were "woven" into new results. In a modern computer these parts are called the memory unit and the CPU. The Analytic Engine also had a key function that distinguishes computers from calculators: the conditional statement.

Babbage befriended Ada Byron, the daughter of the famous poet Lord Byron. Though she was only 19, she was fascinated by Babbage's ideas and through letters and meetings with Babbage she learned enough about the design of the Analytic Engine to begin fashioning programs for the still unbuilt machine. While Babbage refused to publish his knowledge for another 30 years, Ada wrote a series of "Notes" wherein she detailed sequences of instructions she had prepared for the Analytic Engine. The Analytic Engine remained unbuilt but Ada earned her spot in history as the first computer programmer. Ada invented the subroutine and was the first to recognize the importance of looping. Babbage himself went on to invent the modern postal system, cowcatchers on trains, and the ophthalmoscope, which is still used today to treat the eye.

T he

next breakthrough occurred in America. The U.S. Constitution states

that a census

should be taken of all U.S. citizens every 10 years in order to

determine the representation of the states in Congress. While the

very first census of 1790 had only required 9 months, by 1880 the

U.S. population had grown so much that the count for the 1880 census

took 7.5 years. Automation was clearly needed for the next census.

The census bureau offered a prize for an inventor to help with the

1890 census and this prize was won by Herman Hollerith, who proposed

and then successfully adopted Jacquard's punched cards for the

purpose of computation.

he

next breakthrough occurred in America. The U.S. Constitution states

that a census

should be taken of all U.S. citizens every 10 years in order to

determine the representation of the states in Congress. While the

very first census of 1790 had only required 9 months, by 1880 the

U.S. population had grown so much that the count for the 1880 census

took 7.5 years. Automation was clearly needed for the next census.

The census bureau offered a prize for an inventor to help with the

1890 census and this prize was won by Herman Hollerith, who proposed

and then successfully adopted Jacquard's punched cards for the

purpose of computation.

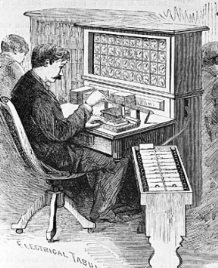

Hollerith's invention, known as the Hollerith desk, consisted of a card reader which sensed the holes in the cards, a gear driven mechanism which could count, and a large wall of dial indicators to display the results of the count.

The patterns on Jacquard's cards were determined when a tapestry was designed and then were not changed. Today, we would call this a read-only form of information storage. Hollerith had the insight to convert punched cards to what is today called a read/write technology. While riding a train, he observed that the conductor didn't merely punch each ticket, but rather punched a particular pattern of holes whose positions indicated the approximate height, weight, eye color, etc. of the ticket owner. This was done to keep anyone else from picking up a discarded ticket and claiming it was his own. Hollerith realized how useful it would be to punch (write) new cards based upon an analysis (reading) of some other set of cards. Complicated analyses, too involved to be accomplished during a single pass through the cards, could be accomplished via multiple passes through the cards using newly printed cards to remember the intermediate results. Unknown to Hollerith, Babbage had proposed this long before.

H ollerith's

technique was successful and the 1890 census was completed in only 3

years at a savings of 5 million dollars.

ollerith's

technique was successful and the 1890 census was completed in only 3

years at a savings of 5 million dollars.

Hollerith built a company, the Tabulating Machine Company which, after a few buyouts, eventually became International Business Machines, known today as IBM. IBM grew rapidly and punched cards became ubiquitous. Your gas bill would arrive each month with a punch card you had to return with your payment. This punch card recorded the particulars of your account: your name, address, gas usage, etc.

M odern

computing can probably be traced back to the 'Harvard Mk I' and

Colossus. Colossus was an electronic computer built in Britain at the

end 1943 and designed to crack the German coding system - Lorenz

cipher.

The 'Harvard Mk I' was a more general purpose electro-mechanical

programmable computer built at Harvard University with backing from

IBM. These computers were among the first of the 'first generation'

computers.

odern

computing can probably be traced back to the 'Harvard Mk I' and

Colossus. Colossus was an electronic computer built in Britain at the

end 1943 and designed to crack the German coding system - Lorenz

cipher.

The 'Harvard Mk I' was a more general purpose electro-mechanical

programmable computer built at Harvard University with backing from

IBM. These computers were among the first of the 'first generation'

computers.

First generation computers were normally based around wired circuits containing vacuum valves and used punched cards as the main (non-volatile) storage medium. Another general purpose computer of this era was 'ENIAC' (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) which was completed in 1946. It was typical of first generation computers, it weighed 30 tones contained 18,000 electronic valves and consumed around 25KW of electrical power. It was, however, capable of an amazing 100,000 calculations a second.

The next major step in the history of computing was the invention of the transistor in 1947. This replaced the inefficient valves with a much smaller and more reliable component. Transistorized computers are normally referred to as 'Second Generation' and dominated the late 1950s and early 1960s. Despite using transistors and printed circuits these computers were still bulky and strictly the domain of Universities and governments.

The explosion in the use of computers began with 'Third Generation' computers. These relied Jack St. Claire Kilby's invention - the integrated circuit or microchip; the first integrated circuit was produced in September 1958 but computers using them didn't begin to appear until 1963. While large 'mainframes' such as the I.B.M. 360 increased storage and processing capabilities further, the integrated circuit allowed the development of Minicomputers that began to bring computing into many smaller businesses. Large scale integration of circuits led to the development of very small processing units, an early example of this is the processor used for analyising flight data in the US Navy's F14A `TomCat' fighter jet. This processor was developed by Steve Geller, Ray Holt and a team from AiResearch and American Microsystems.

On November 15th, 1971, Intel released the world's first commercial microprocessor, the 4004. Fourth generation computers were developed, using a microprocessor to locate much of the computer's processing abilities on a single (small) chip. Coupled with one of Intel's inventions - the RAM chip (Kilobits of memory on a single chip) - the microprocessor allowed fourth generation computers to be even smaller and faster than ever before. The 4004 was only capable of 60,000 instructions per second, but later processors (such as the 8086 that all of Intel's processors for the IBM PC and compatibles are based) brought ever increasing speed and power to the computers. Supercomputers of the era were immensely powerful, like the Cray-1 which could calculate 150 million floating point operations per second. The microprocessor allowed the development of microcomputers, personal computers that were small and cheap enough to be available to ordinary people. The first such personal computer was the MITS Altair 8800, released at the end of 1974, but it was followed by computers such as the Apple I & II, Commodore PET and eventually the original IBM PC in 1981.

Although processing power and storage capacities have increased beyond all recognition since the 1970s the underlying technology of LSI (large scale integration) or VLSI (very large scale integration) microchips has remained basically the same, so it is widely regarded that most of today's computers still belong to the fourth generation.

http://trillian.randomstuff.org.uk

LANGUAGE

DEVELOPMENT