- •Contents

- •Preface

- •Contributors

- •01 Neuroanatomy

- •03 Seizures and Epilepsy

- •04 Disorders of Myelination

- •05 Tumors of the Nervous System

- •06 Headache and Pain Disorders

- •I. Episodic Headache

- •A. Episodic Headaches Lasting More than Four Hours

- •07 Behavioral Neurology

- •08 Movement Disorders

- •09 Diseases of the Nerves

- •10 Diseases of the Muscles

- •I. Bacteria

- •I. Diabetes Mellitus (DM)

- •Index

6

Headache and Pain Disorders

Note: Significant diseases are indicated in bold and syndromes in italics.

I. Episodic Headache

A. Episodic Headaches Lasting More than Four Hours

1.Migraine

a.symptoms: attacks last between 4–72 hours (but may be only 1 hour long in children), and typically involve

i.at least two of the following: unilateral location; pulsating quality of the pain; severe intensity; aggravation by movement

(1)nonpulsatile pain does not exclude the diagnosis of migraine

ii.at least one of the following: nausea, photophobia, phonophobia

b.subtypes of migraine: patients may have any combination of the various subtypes

i.migraine with aura (classic migraine) and without aura (common migraine): phases include

(1)prodrome phase (60%): involves psychological, neurological, and/or constitutional symptoms that develop hours to days before the headache onset

(a)psychological symptoms include depression, euphoria, and restlessness

(b)neurological symptoms include photo/phonophobia and dysphasia

(c)constitutional symptoms include anorexia or hunger, sluggishness, fluid retention, and diarrhea/constipation

(2)aura phase (in 30% of all migraine cases): auras evolve gradually, last 4–60 minutes, and involve positive and negative symptoms such as (Box 6.1)

(a)visual phenomenon: account for 99% of auras; includes the sensation of flashes of light {photopsia}, bilateral scotoma, or a fortification spectrum {teichopsia}

(b)complex visual disturbances, including macro/micropsia or metamorphopsia

(c)paresthesias and sensory loss (30%); clumsiness (20%); apraxias; speech disturbances; déjà vu/jamais vu; delirium

(i)usually these occur in conjunction with a visual aura

(3)headache phase: pain can be bilateral in 40%, and consistently is on one side of the head in only 20% of cases

(a)40% of cases involve sharp stabbing pains lasting a few seconds (i.e., idiopathic stabbing headache; see p. 143)

(4)postdrome phase: involves impaired concentration, fatigue, and/or irritability lasting for several hours following the headache

Box 6.1

In comparison with migranous auras, complex partial seizure auras are shorter ( 5 minutes), produce a change in consciousness, and include automatisms or myoclonic jerks.

Episodic Headache

137

6 Headache and Pain Disorders

138

ii.aura without migraine/migraine equivalent/acephalgic migraine— development of migraine aura phenomena without progression to the headache phase; usually occurs late in life

(1)abdominal migraine—episodes of abdominal pain and nausea often without headache that occur in children with a strong family history of migraine; all other causes of abdominal pain must be excluded prior to establishing the diagnosis

iii.complicated migraine/migraine with prolonged aura—migraines in which the aura phenomena persist beyond the duration of headache, or in which stroke-like focal neurological deficits develop

(1)migrainous infarction: persistence of the neurological deficits of a complicated migraine for 1 week or neuroimaging evidence of infarction

iv.migraine variants

(1)basilar migraine—the migraine aura is followed by any combination of dysarthria, vertigo, tinnitus, hearing loss, diplopia, ataxia, bilateral paresthesias or weakness, or confusion; the headache is usually bilateral and located over the occiput

(a)hemianopic visual auras may become bilateral, leading to complete vision loss

(2)confusional migraine—generally are mild classic migraines that are associated with confusion or agitation; sometimes are triggered by mild head trauma and they rarely recur thereafter

(a)usually a disorder of children who have a history of typical migraine; it also is the typical migraine that occurs in patients with cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL; see p. 67)

(3)ophthalmoplegic migraine—unilateral retroorbital eye pain associated with a cranial nerve palsy (III IV, VI); episodes occur over a period of days to months before spontaneously resolving; however, they are likely to recur

(a)may be related to the Tolosa-Hunt syndrome (see p. 34) because the involved nerves contrast enhance on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and both disorders respond to steroids

(4)hemiplegic migraine—migraine associated with acute-onset weakness and usually confusion, typically lasting 24 hours; often triggered by mild head trauma

(a)subtypes of hemiplegic migraine

(i)familial hemiplegic migraine (75% of cases): involves visual phenomena as well as paresthesias (100%) or aphasia (45%) as auras

1.autosomal dominant inheritance with variable penetration, linked to mutation of the P/Q-type voltagegated calcium channel gene located on chromosome 19 (Box 6.2)

2.20% of patients also exhibit slowly progressive nystagmus and ataxia between hemiplegic migraine attacks

3.may develop into a regular migraine syndrome in adulthood

4.sporadic hemiplegic migraine: indistinguishable from familial form

(ii)hemiplegic migraine associated with benign familial infantile convulsions (rare): mutation of ATP1A2 sodium-potassium ATPase on chromosome 1 (not the mutation that causes benign familial infantile convulsions without migraine—which is on chromosome 16)

Box 6.2

Other mutations of the P/Q voltage-gated calcium channels cause episodic ataxia type 2.

(5)menstrual/menopausal migraine: not associated with aura; headaches typically have a longer duration than regular migraine syndromes

(a)migraine during pregnancy does not affect the rate of spontaneous abortion, toxemia, or fetal malformations in comparison with pregnant women without migraine headaches

(6)status migrainosus—headache phase that lasts for more than 72 hours with headache-free intervals 4 hours (not including sleep)

c.pathophysiology

i.the aura is likely a primary neuronal phenomenon that is triggered by a preceding period of vasoconstriction; reduced blood flow may trigger a brief period of neuronal hyperactivity followed by a prolonged inactivation that spreads outward as a wave moving at 2–6 mm/min across the cortex surface {neuronal spreading depression}

ii.the headache is likely due to a combination of

(1)extracranial arterial vasodilation: initiated by an unknown trigger, but may be promoted by release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P from unmyelinated fibers of CN V

(2)neurogenic inflammation: develops in the region of vasodilation due to plasma protein extravasation as well as the inflammatory effects of neurokinin, CGRP, and substance P released from CN V sensory fibers

(3)decreased inhibition of central pain neurotransmission: abnormal function of second-order neurons in the caudal trigeminal nucleus and cervical dorsal horn (“trigeminocervical complex”) may account for headaches that overlap the trigeminal and cervical innervations

iii.risk factors for migraine

(1)right-to-left cardiac shunt and patent foramen ovale

(2)genetic: tumor necrosis factor (TNF) gene polymorphisms; polymorphisms in upstream regulatory region of serotonin transporter

(3)psychiatric comorbidities: depression

(a)dysthymia and bipolar disorders are associated specifically with migraine with aura

iv.epidemiology: age of onset is typically between 10–15 years of age; new-onset migraine is common in women after age 30, but by that age it becomes very rare in men

v.triggers include bright light, cigarette smoke, fasting, emotional stress, exercise, poor sleep, alcohol, caffeine, aged cheeses or other foods containing tyramine, chocolate, monosodium glutamate, nitrates, and menstruation

d.diagnostic testing

i.neuroimaging: not indicated for classic or common migraine unless it is atypical

(1)MRI demonstrates small T2 hyperintensities in the subcortical white matter that accumulate over time; occasionally infarctionlike changes (i.e., increased diffusion-weighted imaging [DWI] signal) may be seen acutely in cases of complicated migraine

(2)EEG can demonstrate any of several focal abnormalities during attacks (e.g., reduced and asymmetric alpha and theta rhythms, poor reactivity), none of which have diagnostic or predictive value

e.treatment

i.classic and common migraines

(1)acute treatment

(a)triptans: first-line medication for migraines that are of severe

intensity; act as agonists of multiple subtypes of the 5-HT1 receptor both on the vasculature and in brain nociceptive pathways (Table 6–1)

Episodic Headache

139

6 Headache and Pain Disorders

140

Table 6–1 Triptans

Medication |

Routes |

Benefits and limitations |

Metabolism |

|

|

|

|

Almotriptan |

PO |

Minimal side effects |

Hepatic (MAO-A) |

Eletriptan |

PO |

High efficacy; low-recurrence rate |

Hepatic (non-MAO) |

Frovatriptan |

PO |

Long half-life; low-recurrence rate but low |

Hepatic (MAO-A) |

|

|

efficacy; minimal side effects |

|

Naratriptan |

PO |

Low-recurrence rate; minimal side effects |

Mostly renal excretion; no MAO |

|

|

|

interaction |

Rizatriptan |

PO, disintegrating tablet |

High efficacy |

Hepatic (MAO-A) |

Sumatriptan |

PO, SQ, nasal spray |

High efficacy, particularly for SQ preparation |

Hepatic (MAO-A) |

Zolmitriptan |

PO, disintegrating tablet, |

High efficacy |

Hepatic (MAO-A) |

|

nasal spray |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: MAO, monoamine oxidase

(i)most triptans cause vasoconstriction via 5-HT1B receptors, and lipophilic triptans (eletriptan, naratriptan) may also act to reduce the activity of the second-order neurons via 5-HT1B/1D inhibitory receptors

(ii)general side effects of triptan agents include chest pain and paresthesias, therefore triptans should not be given to patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease considering the risk of coronary vasospasm

(b)nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): may be used as first-line medications for migraines of moderate intensity; act as inhibitors of the constitutive (COX-1) and/or inducible (COX-2) cyclooxygenase enzymes that produce prostaglandins

(i)prostaglandins are involved in neurogenic inflammation component of migraine; they also may cause vasodilation and increase the sensitivity of nociceptive pathways

(ii)NSAIDs can be used in low-dose combinations or in combined preparations with caffeine or opioids (Box 6.3)

(iii)side effects include GI ulceration and renal hypoperfusion causing reduced filtration and renal failure

(c)opioids: as effective as triptan agents

(d)ergots: generally are considered as rescue medications because of severe side effects (nausea, diarrhea, psychosis, vasoconstriction in the extremities), strict dose limitations, and parenteral administration routes; act on serotonin, adrenergic, and dopaminergic receptors

(i)ergotamine: not consistently shown to be better than triptans or NSAIDs

(ii)dihydroergotamine: can be administered by nasal spray

(e)antiemetics: should be used in conjunction with other treatments when nausea is a significant feature of the migraine

(2)prophylactic treatments

(a)blockers

(b)antidepressants: amitriptyline, fluoxetine

(c)antiepileptics: valproate, gabapentin, topiramate

(d)methysergide, which is an ergot that acts on 5-HT2 receptors

(i)cannot be used for more than 6 months at a time because of retroperitoneal fibrosis

Box 6.3

Acetaminophen does not have a clear benefit in migraine treatment.

(e)dietary supplements: riboflavin, butterbur extract, coenzyme Q10

(f)relaxation therapy

ii.migraine during pregnancy: to avoid harming the fetus, limit treatments to IV fluids, acetaminophen, opioids, and metoclopramide (for nausea)

iii.status migrainosus

(1)fluid and electrolyte replacement

(2)medication detoxification

(3)IV therapy (Box 6.4)

(a)headache: dihydroergotamine (DHE) glucocorticoids, ketorolac

(b)nausea: prochlorperazine, metoclopramide

(4)establish migraine prophylaxis thereafter

2.Tension-type headache

a.symptoms: lacks any prodromeor aura-like symptoms

i.diffuse pain of mild-to-moderate intensity and aching or squeezing quality that is not incapacitating or worsened by head movements; pain often involves the neck and/or jaw (Box 6.5)

(1)the pain often develops a pulsatile quality if it becomes severe

(2)occasionally involves mild migrainous symptoms (nausea, photo/ phonophobia); more commonly is associated with fatigue or lightheadedness

(3)can be triggered by sleep deprivation or emotional stress

ii.tenderness of the pericranial muscles and/or temporomandibular joint is an unreliable finding

b.pathophysiology

i.headaches are associated with a mild diffuse vasoconstriction and low serum magnesium levels (which can cause vasoconstriction); similar abnormalities are also observed in other types of headache as well

ii.headache frequency and severity are associated with high levels of anxiety and depression that are not necessarily pathological in severity

c.diagnostic testing: the spontaneous activity of the cranial muscles on an EMG is not higher in patients with tension-type headaches than it is in normal controls

d.treatment

i.regular sleep and exercise; relaxation therapy

ii.medical treatments

(1)NSAIDs; acetaminophen; caffeine-containing compounds; codeine

(a)triptan agents are effective against tension-type headaches only in patients who have coincident migraines

(2)anesthetic or botulinum toxin injection into tender cranial muscles

Box 6.4

Both headache and nausea treatments should be used together, even if the nausea is minor.

Box 6.5

Distinguish tension-type headache from cervical spine disease by the lack of exacerbation with movements; from temporomandibular joint disease by the lack of jaw clicking or exacerbation with chewing; both disorders will have joint tenderness.

Episodic Headache

B. Episodic Headaches Lasting Less than Four Hours

1.Cluster headache

a.symptoms: severe throbbing or stabbing pain located around the eye and orbit that may radiate to the jaw, neck, or temporal area; attacks last 45–90 minutes and occur regularly and repetitively over a period of 6–12 weeks before spontaneously remitting (Box 6.6)

i.attacks occur at the same time of day and clusters of attacks occur at the same time of the year, although they become less regular over time

(1)headache can be triggered by sleep deprivation, alcohol, organic solvents, or emotional stress

ii.patients are agitated and restless during the headache (unlike migraine)

Box 6.6 |

|

The Cluster Headache Phenotype |

|

Deep nasolabial furrows, peau d’orange |

|

skin, telangiectasias {leonine face} |

|

Masculinized face in women |

|

High-stress (type A) personality |

141 |

|

6 Headache and Pain Disorders

iii.pain is strictly unilateral, always occurring on the same side

iv.migrainous features (e.g., nausea, phono/photophobia) occur in 50%; rarely associated with aura

v.attacks are triggered by REM sleep, which is shortened by sleep deprivation, therefore patients may avoid sleep

vi.attacks are associated with multiple autonomic features: ptosis (70%); conjunctival injection (80%); lacrimation (80%); nasal congestion and rhinorrhea; bradycardia leading to syncope; hypertension

b.pathophysiology: likely involves the cavernous segment of the carotid artery and the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the supraoptic region of the hypothalamus because

i.attacks are associated with dilation of the ophthalmic artery and cavernous carotid, although this is not specific to cluster headache and can be induced to a lesser degree by pain applied to the CN V-1 region of the face

(1)patients exhibit a narrow middle cranial fossa, suggesting venous drainage abnormalities in the cavernous sinus

ii.patients exhibit an abnormal circadian rhythm of melatonin release from the pineal gland, which is under the control of the suprachiasmatic nucleus

c.epidemiology: typical onset between 25–30 years of age; 5:1 male predominance

i.occasional families exhibit autosomal dominant inheritance

ii.associated with heavy alcohol and tobacco use

d.treatment

i.good sleep hygiene with regular hours

ii.acute medical treatment

(1)oxygen inhalation: 100% oxygen at 7 L/min for 15 minutes via non-rebreather mask gives relief in 70%

(2)sumatriptan: effective in 70% when given by the SQ route; not effective as an abortive therapy when given orally

(3)dihydroergotamine (DHE) IV

(4)intranasal lidocaine, as an adjunct therapy

iii.prophylactic medical treatments: to be used during the cluster, then discontinued

(1)glucocorticoids: effective at headache prevention but headaches frequently recur during tapering

(2)lithium

(3)DHE

(4)valproate: particularly effective in patients with migrainous features

(5)topiramate

(6)methysergide

(7)intranasal capsaicin

(8)melatonin, as an adjunct therapy

iv.surgical treatment: trigeminal rhizotomy or microvascular decompression of the trigeminal/gasserian ganglia

2.Paroxysmal hemicrania

a.symptoms: severe throbbing or stabbing pain that is usually located in the orbital, supraorbital, and/or temporal areas; may have anywhere from a few to dozens of attacks lasting 2–45 minutes each

i.pain is strictly unilateral, always occurring on the same side

ii.attacks are associated with at least one of the following autonomic features: conjunctival injection; lacrimation; nasal congestion; rhinorrhea;

142 |

ptosis; eyelid edema |

iii.attacks can be triggered by pressure on the cervical nerve roots or cervical vertebrae

b.pathophysiology: headaches are related to pronounced increases in ipsilateral ocular blood flow and intraocular pressure

c.treatment: scheduled indomethacin is uniformly effective, and this responsiveness is necessary to establish the diagnosis

3.Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headaches with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT) syndrome

a.symptoms: unilateral stabbing or electrical pain of sudden onset lasting2 minutes, centered around the eye but radiating to the forehead, face, temple, and oropharyngeal cavity; upwards of 100 attacks per day may occur

i.periods of headaches last from several days to months followed by spontaneous remission ranging from weeks to years

ii.attacks are triggered by tactile stimulation to the head or neck (i.e., involving CN V and C2 distributions)

(1)no refractory period exists after a triggered attack, unlike trigeminal neuralgia

iii.attacks are associated with at least one of the following autonomic features: conjunctival injection; lacrimation; nasal congestion and rhinorrhea; ptosis; eyelid edema

b.pathophysiology: unknown

c.treatment: carbamazepine, which has limited effectiveness; verapamil actually worsens the condition

4.Hypnic headache

a.symptoms: unilateral or bilateral throbbing headache without associated migrainous or autonomic features that last 60 minutes, occurring 1–3 times per evening; headaches develop only during REM sleep, rarely during daytime naps

b.pathophysiology: unknown

c.epidemiology: occurs only in patients 60 years of age

d.treatment: lithium

5.Idiopathic stabbing headache/ice-pick headache/abs-and-jolts syndrome/ ophthalmodynia

a.symptoms: sharp pain lasting 1 second that causes a shock-like response (“jolt”); pain is typically unilateral, located in the orbit, forehead, and/or temple

i.attacks usually occur in clusters lasting a few days, followed by a period of remission

ii.involves migrainous or autonomic symptoms, and triggers

iii.60% have an additional subtype of headache, usually migraine

iv.10% have episodes involving ipsilateral conjunctival hemorrhage

b.pathophysiology: unknown, but has a high coincidence of ocular pathology (glaucoma, cataracts, amblyopia)

c.treatment: indomethacin, verapamil

II. Chronic Headaches

1.Definition: any headache type occurring more than 15 days per month

2.General pathophysiology (Box 6.7)

a.development of chronic headache: 75% of cases develop from episodic migraine {transformed migraine}, 10% of cases develop from episodic tensiontype headache, and 15% of cases develop without a previous headache history

i.chronic headache that does not develop from an existing episodic headache disorder is worrisome for having an underlying pathophysiology process (secondary chronic headache)

Chronic Headaches

Box 6.7 |

|

Secondary Chronic Headaches |

|

Posttraumatic headache |

|

Cervical spine disorders |

|

Cranial nerve injuries |

|

Ophthalmic disorders: glaucoma, corneal |

|

erosions, refractive errors, heterotropia/ |

|

phoria |

|

Vascular cranial disorders: arteriovenous |

|

malformation, giant cell arteritis, cerebral |

|

dissection, subdural hematoma |

|

Nonvascular cranial disorders: highor |

|

low-intracranial pressure, infection, |

|

neoplasm, Chiari malformation, inflam- |

|

matory disorders (sarcoidosis, Bechet’s |

|

syndrome) |

|

Oromandibular and temporomandibular |

|

disorders |

|

Sinus infections, ear disorders |

143 |

|

6 Headache and Pain Disorders

144

b.genetics

i.chronic tension-type headache exhibits multifactorial inheritance

ii.chronic cluster headache exhibits autosomal dominant inheritance

c.epidemiology: 4% prevalence for all subtypes in the general population versus 12% for episodic migraine and 38% for episodic tension-type headache

i.sex: overall relative risk in females 2–9 depending upon the subtype; male predominance is observed only with chronic cluster headache

d.associated conditions

i.psychiatric disorders: most common are anxiety disorders (45%), mood disorders (35%), and somatoform disorders (5%); coexisting psychiatric disorders often remit following successful chronic headache treatment

ii.medication overuse (40%)

(1)defined as the use of

(a)at least three simple (e.g., single-agent, nonbarbiturate, nonsedative) analgesic medications per day for at least 5 days per week

(b)triptans and/or multiagent analgesics on at least 3 days per week

(c)opioids and/or ergots on at least 3 days per week

(2)medication overuse leads to

(a)“rebound headaches” that are confused with the underlying headache disorder, thereby encouraging additional medication usage

(b)headaches that are refractory to prophylactic medications

(c)systemic toxicities of excessive analgesic use

3.Primary chronic headache 4 hours in duration

a.chronic migraine/transformed migraine—accounts for 65% of chronic headache

i.symptoms: chronic headache that is persistent for 3 months, and typically has

(1)a period of increasing headache frequency with decreasing severity of migrainous symptoms

(2)pain that is still throbbing in nature, although it is less severe than episodic migraine and involves features of other types of headaches

(a)chronic headaches with migraine and tension-type features should be considered as chronic migraine and treated as such

(3)persistence of triggers from the episodic migraine

ii.treatment

(1) prophylaxis: amitriptyline, fluoxetine, doxepin, tizanidine,

blockers, anticonvulsants (valproate, topiramate)

(2)acute attack: triptans, long-acting NSAIDs (e.g., diflunisal, naproxen, nabumetone, oxaprozin, piroxicam, phenylbutazone)

b.chronic tension-type headache—accounts for 30% of chronic headache

i.symptoms: chronic headache must be persistent for 6 months, and typically has

(1)pain that is pressing or tightening in quality, mild to moderate in severity, and bilaterally located; pain is not aggravated by routine physical activity

(2)pain that is associated with at most only one migrainous symptom

(3)tenderness of pericranial muscles that also exhibit increased electromyographic activity at rest

ii.treatment

(1)prophylaxis: amitriptyline, tizanidine, botulinum toxin injection into tender cranial muscles

(2)acute attacks: long-acting NSAIDs

c.hemicrania continua—does not reliably develop from an episodic headache condition (i.e., often is chronic at its onset)

i.symptoms: chronic headache persistent for 1 month that is characterized by

(1)unilateral, continuous pain of varying nature and severity

(2)at least one autonomic symptom (conjunctival injection, ptosis, lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, eyelid edema, miosis, facial sweating) during periods of severe headache

(3)an absence of triggers

ii.treatment: indomethacin PRN (as needed) for acute attacks, or scheduled for prophylaxis

(1)complete symptomatic relief following indomethacin treatment is essentially a diagnostic test for hemicrania continua

4.Chronic headaches 4 hours in duration: rarely cause chronic headache

a.chronic cluster headache

i.symptoms: 1–8 attacks of pain per day lasting 15–180 minutes (versus 45–90 minutes for episodic cluster headache) with clusters of daily attacks occurring regularly at the same time, wherein the clusters last 1 year in duration with 14 days of remission

(1)pain has a compressive or boring quality

(2)pain is strictly unilateral, and always on the same side; pain is typically located around the orbit and temporal region and occasionally radiates to the jaw and neck

(3)attacks are associated with autonomic symptoms (conjunctival injection, ptosis, lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, eyelid edema, miosis, facial sweating), but migrainous symptoms occur in 50%; rarely is associated with an aura

(4)headache triggers include REM sleep, alcohol, and nitrates

ii.treatment

(1)medical treatment

(a)prophylaxis: lithium, verapamil, methysergide, anticonvulsants (valproate, topiramate)

(b)acute attacks: oxygen supplementation, triptans, intranasal lidocaine

(2)surgical treatment: gamma-knife radiosurgery, trigeminal rhizotomy, or trigeminal root section for medically refractive cases

b.chronic paroxysmal hemicrania

i.symptoms: 4 attacks per day of headache lasting 2–45 minutes, wherein the attacks

(1)involve severe periorbital and temporal region boring or throbbing pain, which causes agitation and restlessness

(a)the pain is strictly unilateral, and always on the same side of the head

(2)are associated with autonomic symptoms (conjunctival injection, ptosis, lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, eyelid edema, miosis, facial sweating) ipsilateral to the pain; migrainous symptoms absent

(3)occur irregularly throughout the day or night, and can be triggered by head movements or pressure applied to cervical region (in 10% of cases)

ii.treatment: indomethacin should completely alleviate the headache, as in hemicrania continua

Chronic Headaches

145

6 Headache and Pain Disorders

146

5.General diagnostic testing

a.neuroimaging

i.brain MRI or CT scan

(1)chronic migraine does not require neuroimaging if it developed from episodic migraine, if it is symptomatically stable, and if the patient’s neurological examination is normal

(2)chronic tension-type headache: neuroimaging identifies a surgically treatable abnormality in 1.5% of patients compared with 0.4% of patients without headaches

(3)other chronic headaches: undefined yield of neuroimaging; they are all so rare; that they are aggressively evaluated

ii.MR venogram: venous sinus thrombosis can be observed in 10% of chronic migraine or chronic tension-type headache patients, although its significance is unclear

b.lumbar puncture: opening pressure may be 20 cm H2O in 20% of chronic headache patients but only half of chronic headache patients with elevated intracranial pressure have papilledema

6.General treatment

a.patient education

i.encourage regular sleep habits, exercise involving stretching, and regular meals

ii.dietary supplementation with L-5-hydroxytryptophan may reduce analgesic use during detoxification

b.identify comorbid psychiatric factors and treat appropriately

c.medication detoxification (Box 6.8)

i.gradually taper barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and opioids

ii.butalbital-containing analgesics can be substituted with phenobarbital, which can then be gradually tapered

iii.gradually switch from short-acting NSAIDs (including most over- the-counter medications except for naproxen) to long-acting NSAIDs

d.adjunctive treatment

i.psychotherapy: stress management, relaxation therapy, and biofeedback has been proven efficacious

ii.physiotherapy: cervical spine manipulation, massage, transcutaneous electrical neural stimulation (TENS), and ergonometric review have limited evidence supporting their use in the treatment of chronic tension-type headache

iii.acupuncture is proven ineffective

7.General prognosis

a.response to preventative medication takes up to 10 weeks following detoxification

b.60% of patients will revert to an episodic headache disorder

c.failure to improve following aggressive management is highly suggestive of an untreated psychiatric disorder

III. Special Headache Disorders

1.Pseudotumor cerebri

a.pathophysiology: a condition of elevated intracranial pressure that is idiopathic by definition; may be caused by reduced cerebrospinal fluid resorption or increased cerebrospinal fluid production

i.risk factors include obesity, female sex, withdrawal from glucocorticoid use, Addison’s disease, and the use of certain medications (nalidixic acid, nitrofurantoin, ketoprofen, vitamin A, isotretinoin, anabolic steroids)

Box 6.8

Indications for In-Hospital

Detoxification

Comorbid medical conditions that require monitoring

Detoxification from opioids, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, or ergots

Failed outpatient detoxification

(1)no relation to pregnancy or menstruation

(2)no proven relation to glucocorticoid use, only glucocorticoid withdrawal

ii.occasionally associated with Behçet’s syndrome (iritis, oral and genital ulcers)

b.symptoms

i.daily headache, usually diffuse and throbbing in nature; pain is exacerbated by eye movements and is associated with neck stiffness

ii.visual symptoms

(1)acute: transient unilateral loss of vision {visual obscurations} due to optic nerve ischemia; diplopia caused by CN VI palsy

(2)chronic: enlargement of the blind spot, peripheral visual field constriction, and scotomas caused by papilledema

iii.pulsatile tinnitus

c.diagnostic testing

i.neuroimaging to evaluate for mass lesions and MR venography to evaluate for venous sinus thrombosis

ii.lumbar puncture demonstrates elevated intracranial pressure with Lundberg waves (see p. 35), but no abnormalities of the cerebrospinal fluid

d.treatment

i.weight loss with fluid and salt restriction

ii.medical treatment: diuretics (acetazolamide, furosemide), digoxin, glucocorticoids

(1)lumbar puncture lowers intracranial pressure only for a few hours, so repeated lumbar puncture is unlikely to be of much benefit

iii.surgical treatment

(1)optic nerve sheath fenestration, which is effective only for visual symptoms

(2)lumboperitoneal shunt

2.Spontaneous intracranial hypotension

a.pathophysiology: can be caused by decreased intracranial pressure or low ventricular volume resulting from

i.leaks in the meninges that develop most commonly in the spine but occasionally in the skull base (e.g., cribriform plate); leaks can develop as a consequence of minor trauma (even from injury caused by bony or vertebral disk abnormalities of the spine), the Valsalva maneuver, or congenital weakness of the meninges (e.g., as in Marfan’s syndrome, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease)

ii.peripheral hypovolemia

b.symptoms

i.headache when standing that is relieved by lying and that often involves the neck and upper back

ii.tinnitus and/or vertigo, possibly because of traction on CN VIII or abnormalities of the perilymphatic fluid in the inner ear

c.diagnostic testing

i.lumbar puncture demonstrates a low opening pressure that may even be negative; mildly elevated protein and pleocytosis levels may occur

ii.cisternography demonstrates the site of radiolabel leakage or its accumulation in a meningeal diverticula, as well as the lack of accumulation of the radiolabel over the cerebral convexities 24 hours after administration; early accumulation ( 4 hours after administration) of the radiolabel in the kidneys is also suggestive of a cerebrospinal fluid leak

Special Headache Disorders

147

6 Headache and Pain Disorders

148

iii.neuroimaging may demonstrate reduced ventricle sizes, meningeal enhancement, and descent of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum (Chiari I malformation; see p.); extraaxial subdural fluid collections representing meningeal diverticula are rarely observed

d. treatment

i.bed rest and increased fluid intake

ii.caffeine; theophylline; glucocorticoids

iii.epidural blood patching: effective in 30% of cases of lumbar punctureinduced headaches; it is minimally effective in spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leaks

iv.intrathecal fluid administration

v.surgical closure of an identified meningeal defect

3.Trigeminal neuralgia/tic douloureux

a.pathophysiology: irritation of the nerve root at the site where central and peripheral myelin meet {Obersteiner-Redlich zone}; irritation is typically caused by demyelination (e.g., multiple sclerosis) or compression by a mass lesion (e.g., a vascular loop, meningioma)

i.pain attacks can be triggered by somatosensory stimulation of the trigeminal distribution may involve ephaptic transmission between mechanoreceptive fibers and nociceptive fibers at the site of irritation (Box 6.9)

ii.pain attacks may also involve the increased sensitivity of second-order nociceptive and mechanoreceptive neurons in the spinal trigeminal nucleus

iii.may occur in conjunction with hemifacial spasm {tic convulsif} with large intracranial lesions

b.symptoms: clusters of severe sharp pain lasting several seconds to a few minutes that is triggered by mild somatosensory stimulation to various parts of the face; patients may have dull pain in the affected regions between triggered attacks

i.distribution of pain: CN V2 V3 all three divisions CN V2 only CN V3 only

ii.pain never crosses the midline, nor do patients with bilateral disease have simultaneous bilateral attacks

iii.sensory loss in the trigeminal divisions affected by pain (Box 6.10)

c.diagnostic testing

i.neuroimaging: surgically treatable abnormalities are usually only detected by MRI in patients with facial numbness or who exhibit progressive disease; MRA may disclose vascular abnormalities

ii.trigeminal evoked potentials: an abnormal study is highly indicative of a mass lesion

d.treatment: all treatments appear to be less effective in those patients who have dull pain between triggered attacks

i.medical treatment: antiepileptics (carbamazepine, gabapentin); pimozide; clonazepam

(1)baclofen can be given as an adjunct medication with antiepileptics

ii.surgical treatment

(1)microvascular decompression: separation of the nerve from any aberrant vascular loops (usually from the superior cerebellar artery) by means of a suboccipital craniotomy

(a)the preferred surgical treatment in patients 65 years of age who have more than a 5-year life expectancy; effective in 80% of cases

Box 6.9

Other Diseases of Possible Ephaptic

Transmission at the Obersteiner-

Redlich Zone

Hemifacial spasm

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia

Box 6.10

Trigeminal Dysesthesia

A continuous burning pain in a region of the face caused by a mild injury to CN V (e.g., tooth extraction, zoster infection); does not involve triggers

Involved regions of the face exhibit abnormal skin temperature

(2) percutaneous trigeminal rhizotomy using glycerol or radiofrequency ablation: lesioning of the nerve roots behind the gasserian ganglia is achieved by advancing the surgical tool through the soft tissues of the cheek into Meckel’s cave via the foramen ovale

(a) particularly useful in cases of multiple sclerosis

(b) often causes significant sensory loss in the CN V distribution

(3) stereotactic radiosurgery of the trigeminal ganglia: generally reserved for patients who have failed other surgical treatments

4. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia

Figure 6–1 Nerves of the occipital area. (From McKhann GM et al. Q&A

a.pathophysiology: likely an irritative disorder of Color Review of Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. Stuttgart, Germany:

the nerve root entry zone of CN IX and/or CN X caused by an aberrant intracranial vascular loop;

cases have been associated with extracranial pathology such as oropharyngeal mass lesions

b.symptoms: sharp pain in the throat or ear, lasting several seconds to a few minutes; attacks may involve bradycardia that causes syncope

i.triggers include swallowing, yawning, and sneezing

ii.occurs with trigeminal neuralgia in 10% of cases

c.diagnostic testing: MRI studies should cover the head and neck to evaluate for causative lesions

d.treatment

i.medical treatment: as per trigeminal neuralgia; topical anesthetics to the oropharynx

ii.surgical treatment: microvascular decompression

5.Greater occipital neuralgia

a.pathophysiology: typically caused by trauma to the greater or lesser occipital nerves, as prolonged compression or after whiplash movements (Fig. 6–1)

b.symptoms: paroxysmal attacks of sharp pain radiating upward along the occiput from the neck or skull base that is usually triggered by neck extension or other neck movements; sensory loss over the C2 dermatome may occur

c.treatment: cervical collar; NSAIDs, muscle relaxants; local anesthetic or glucocorticoid injections

IV. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

1.Subtypes

a. CRPS-1/reflex sympathetic dystrophy

i.pathophysiology: develops after minor injury (e.g., trauma, surgery) in the absence of an obvious nerve lesion; the injury may occur in the limbs, thorax, or abdomen, and the symptoms can extend outside of the distribution of a single nerve

(1)some but not all patients have abnormal baseline sympathetic activity (e.g., abnormal local skin temperature) and responsiveness (e.g., inappropriate sweating) in the affected regions

ii.specific symptoms

(1)pain that is out of proportion to the severity of the inciting injury {hyperpathia} that often spreads to neighboring areas, which is perceived to be deep in the extremity; usually pain attacks occur spontaneous but they also are inducible by movement and palpation of the affected area

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

149

6 Headache and Pain Disorders

(2)dysesthesias and sensory loss to all modalities in the painful area (50%)

(3)skin changes, meaning hyperhidrosis and warm skin (acutely after injury) or hypohidrosis and cold skin (chronic state)

(4)weakness, decreased range of motion, tremor, and/or dystonia in the affected area

b.CRPS-2/causalgia

i.pathophysiology: develops after injury to a large nerve; abnormal sympathetic activity and reactivity are apparent in the affected region, as per CRPS-1

ii.symptoms

(1)hyperpathia, dysesthesia, and sensory loss as per CRPS-1, but no movement abnormalities

(2)skin changes: cold skin; hyperhidrosis; edema; smoothing and mottling; increased hair growth occurs in chronic state

2.General symptoms

a.psychiatric dysfunction: patients exhibit poor coping skills, depression, and/or anxiety disorders

b.symptoms are sensitive to emotional factors, stress, changes in environmental temperature, and limb position

3.Diagnostic testing: no tests are of proven accuracy in establishing the diagnosis

a.subcutaneous norepinephrine injection causes pain in cases of CRPS that involve sympathetic hyperactivity

b.nerve conduction studies demonstrate no evidence of nerve injury in CRPS-1, unlike CRPS-2

c.quantitative sensory testing to determine any asymmetry in sensory thresholds

d.autonomic testing: laser Doppler flowmetry, infrared thermography, quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test

4.Treatment

a.medications: clonidine; tricyclic antidepressants; carbamazepine; type Ib antiarrhythmic agents (lidocaine, mexiletine, tocainide); glucocorticoids

b.regional sympathetic blockade: ineffective for pain control but may be useful against edema

c.TENS

d.physical therapy

V. Fibromyalgia

1.Pathophysiology

a.biological

i.subjective reporting of increased pain sensitivity and an increased temporal summation of repetitive painful stimuli is paralleled by

(1)lowered threshold for activation of pain-sensitive brain regions, as demonstrated by PET scan

(2)increased cortical somatosensory evoked potential amplitudes to standard stimuli

ii.increased substance P levels in cerebrospinal fluid suggest hyperactive nociceptive neurotransmission

iii.baseline hypoperfusion of the caudate and thalamus is also seen in other chronic pain conditions

b.psychological: unclear causative relationship to emotional stress, although it seems to exacerbate the symptoms; fibromyalgia is more

150common in patients with depression, anxiety disorders, and somatoform disorders

2.Epidemiology: more common in women

3.Symptoms

a.multifocal musculoskeletal pain, generally continuous in nature although the location of the painful sites can change over time

i.generally develops after a focal, chronic pain condition (e.g., low back pain)

b.fatigue and nonrestorative sleep

4.Diagnostic testing: polysomnography demonstrates reduced time spent in slow-wave sleep stages 3 and 4

5.Treatment

a.graded exercise programs, which are particularly useful in the subgroup of fibromyalgia patients that demonstrates phobic-like avoidance of physical activity

b.behavioral psychotherapy

c.medications: antidepressants; muscle relaxants; adenosyl-methionine and niacin supplementation

6.Prognosis: 10% exhibit long-term improvement

VI. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Neurasthenia

1.Pathophysiology

a.biological: patients exhibit an increase—(not the normal decrease) in adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol levels in response to serotonin agonists and exhibit reduced ACTH and cortisol responses to CRH, suggesting abnormal hypothalamic-pituitary function

b.psychological: patients have an increased use of avoidance-escape behavioral strategies, suggesting maladaptive coping skills

2.Epidemiology: more common in women; unclear relation to socioeconomic status

a.increased risk in family members of an affected individual

b.high coincidence with fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and multiple chemical sensitivities

3.Symptoms

a.fatigue 6 months in duration, typically beginning after a nonspecific flu-like illness and that is disproportionately exacerbated by exercise

b.at least four of the following: polyarthralgia, polymyalgia, impaired memory or concentration, headache, nonrestorative sleep, sore throat, lymph node tenderness

4.Diagnostic testing

a.neuropsychological testing: minimal impairment of concentration and memory function is usually delectable

b.polysomnography does not reliably demonstrate any abnormality

5.Treatment

a.graded exercise programs

b.behavioral psychotherapy

c.low-dose glucocorticoids; tricyclic antidepressants; NSAIDs; magnesium supplements

6.Prognosis: 10% exhibit long-term improvement; 60% have impaired work performance

VII. Low Back Pain

1.Pathophysiology: cause for pain can be identified in only 20% of cases

a.soft tissue and bone disorders: includes vertebral body disease, spinal stenosis, degenerative facet disease, and muscle injury (either primary or due to overuse from stabilization of misaligned bony structures)

Low Back Pain

151

6 Headache and Pain Disorders

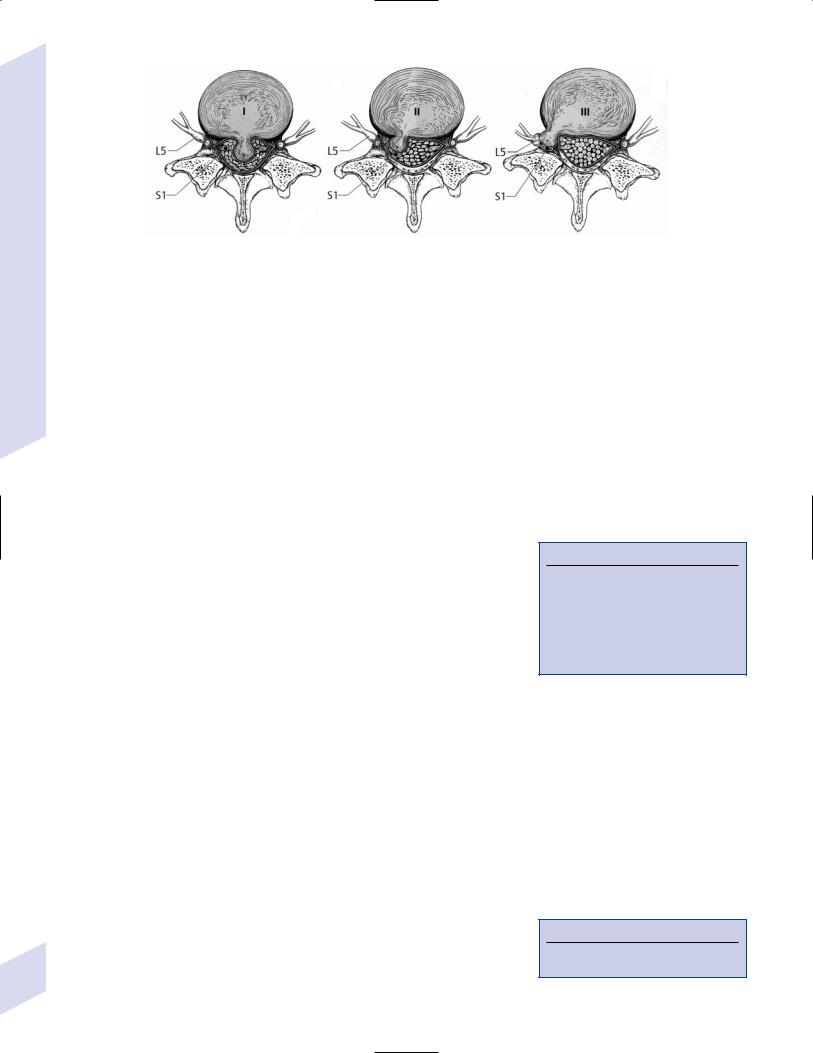

Figure 6–2 Disk herniations. (A) Central disk herniation compresses the |

level above the disk and occasionally the level from the level of the disk. |

dural sac (e.g., cauda equina). (B) Intermediate disk herniation com- |

(From Hosten N, Liebig T, CT of the Head and Spine. Stuttgart, Germany: |

presses the dural sac and the nerve root from the level below the disk. |

Georg Thieme; 2002:346, Fig.12.58. Reprinted by permission.) |

(C) Extreme lateral disk herniation compresses the nerve root from the |

|

b.disk herniation: rupture or protrusion of the nucleus pulposus through the annular fibers of the disk occurs after tearing of the inner annular fibers from rotational or sliding (not compressive) movements of the adjacent vertebral bodies; pain is generated by injury to the disk itself and/or by compression of nearby structures (e.g., spinal ligaments, dura, nerve roots)

i.location of disk herniations (Fig. 6–2)

(1)extreme lateral herniation hits the nerve root from underneath (e.g., an L4–5 disk hits the L4 nerve root)

(2)intermediate lateral herniation hits the nerve root from the top (e.g., an L4–5 disk hits the L5 nerve root)

(3)central herniation hits multiple nerve roots in the cauda equina that are derived from several spinal cord levels below the vertebral level of the herniation

c.nerve root compression {radiculopathy}: can be caused by facet hypertrophy, osteophyte formation, disk herniation, or diseases that involve the ganglia (Box 6.11)

2.Symptoms (Table 6–2)

a.pain radiating down the lower extremity that is relieved by knee and hip flexion and that is exacerbated by straight leg raises, immobility, or the Valsalva maneuver

b.referred pain and paresthesias to the flank and buttocks in cases with significant soft tissue disease; the pain reliably does not extend below the knee, but its location does not identify the site of the lesion

3.Diagnostic testing: In the absence of neurological deficits or any likelihood of a secondary cause for the back pain, no neuroimaging should be performed until several weeks of medical management has failed

a.in asymptomatic persons, 50% exhibit degenerative joint disease and 20% exhibit disk herniations on neuroimaging

b.disk herniations can resolve spontaneously on sequential neuroimaging studies

Box 6.11

Noncompressive but Painful Diseases of the Nerve Roots

Diabetes (proximal diabetic neuropathy, see p.)

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Lyme disease, syphilis (tabes dorsalis)

Guillain-Barre syndrome

Table 6–2 Lumbar Radiculopathies

|

|

Pain is located in |

Weakness is in |

Decreased reflex in |

|

|

|

|

|

|

L4 nerve root |

Anterior thigh |

Knee extension |

Patellar tendon |

|

L5 nerve root |

Posterior thigh |

Foot dorsiflexion; ankle |

Quadriceps femoris |

|

|

and calf |

inversion and eversion; |

|

|

|

|

hip extension/abduction |

|

|

|

|

(Box 6.12) |

|

|

S1 nerve root |

Posterior thigh, |

Foot plantar flexion |

Ankle |

152 |

|

calf, and foot |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Box 6.12

Inversion and hip extension distinguish an L5 lesion from peroneal nerve injury.

4.Treatment

a.medical treatment

i.minimal, if any, bed rest; continue with nonexertional daily activities

ii.NSAIDs, muscle relaxants

iii.no benefit of traction or TENS

b.surgical treatment: lumbar spinal fusion; laminectomy; diskectomy; vertebroplasty

5.Prognosis: 80% of cases improve with NSAIDs, muscle relaxants, and physical therapy

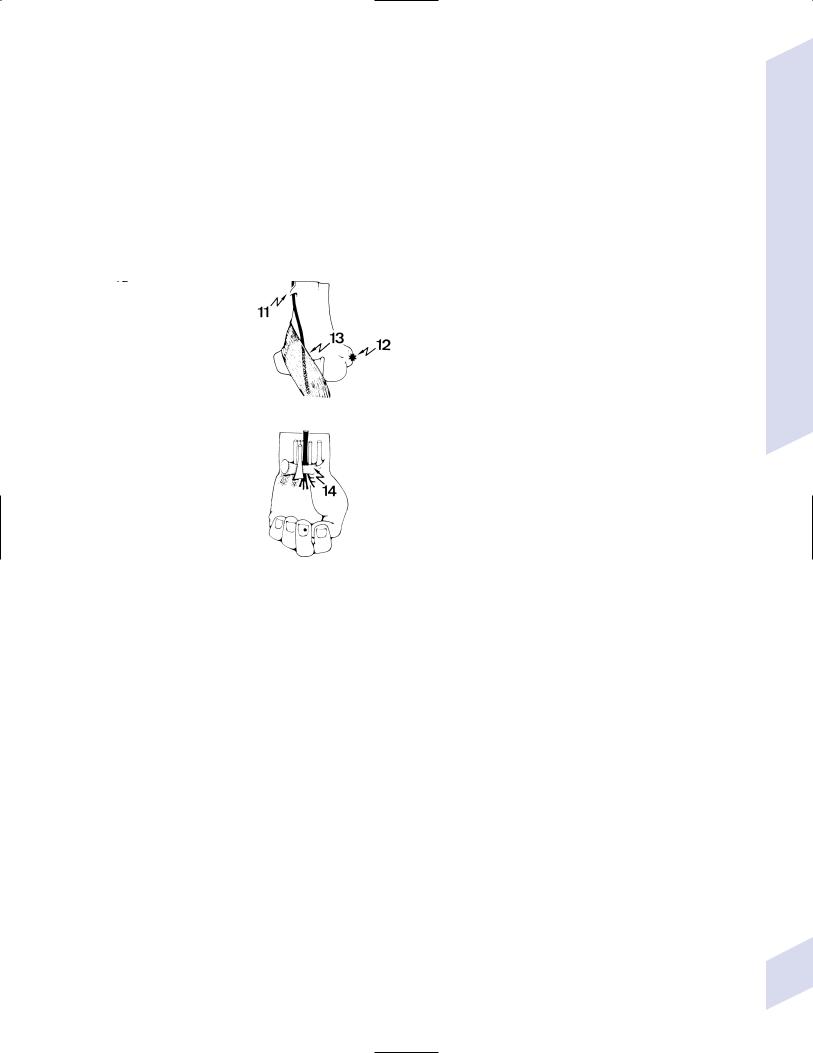

VIII. Neck, Shoulder, and Arm Pain (Fig. 6–3)

Figure 6–3 Common causes of shoulder and arm pain. 1, syringomyelia; 2, root neurinoma; 3, spondylosis with root encroachment; 4, Pancoast tumor; 5, referred pain; 6a, cervical rib; 6b, scalenus tunnel; 7a, first rib; 7b, clavicle; 8a, supraspinatus muscle; 8b, supraspinatus muscle; 9, shoulder arthritis; 10, bone sarcoma; 11, supracondylar humeral process; 12, radial epicondylitis; 13, median nerve–pronator teres muscle; 14, carpal tunnel syndrome. (From Mumenthaler M, Neurological Differential Diagnosis. 2nd ed. Stuttgart, Germany: Georg Thieme; 1992:150, Fig. 55. Reprinted by permission.)

Neck, Shoulder, and Arm Pain

153