- •Preface

- •Content

- •Contributors

- •2 Practicing Evidence-Based Surgery

- •5 Surgical Critical Care

- •7 Shock

- •8 Surgical Bleeding and Hemostasis

- •11 Head and Neck Lesions

- •16 Acute and Chronic Chest Pain

- •17 Stroke

- •18 Surgical Hypertension

- •19 Breast Disease

- •20 Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •21 Abdominal Pain

- •23 Abdominal Masses: Vascular

- •24 Jaundice

- •25 Colon and Rectum

- •26 Perianal Complaints

- •28 The Ischemic Lower Extremity

- •29 The Swollen Leg

- •30 Skin and Soft Tissues

- •31 Trauma Fundamentals

- •33 Musculoskeletal Injuries

- •34 Burns

- •36 Neonatal Intestinal Obstruction

- •37 Lower Urinary Tract Disorders

- •38 Evaluation of Flank Pain

- •39 Scrotal Disorders

- •40 Transplantation of the Kidney

- •41 Transplantation of the Pancreas

- •42 Transplantation of the Liver

- •Index

39

Scrotal Disorders

Robert E. Weiss

Objectives

1.To discuss the diagnosis and treatment of the undescended testicle. Be sure to consider the age of the patient.

2.To generate a list of potential diagnoses for the patient who presents with pain or a mass in the scrotum. Be sure to:

•Discuss testicular versus extratesticular origins

•Discuss benign versus malignant causes

•Discuss emergent versus nonemergent causes

3.To list the history and physical exam findings that help differentiate etiologies. Be sure to discuss the following issues:

•Pain—presence, absence, onset, severity

•Palpation—distinguish testicular from extratesticular (adnexal) mass

•Transillumination

4.To discuss the diagnostic algorithm for scrotal swelling and/or pain.

5.To discuss the treatment of nonmalignant causes of scrotal swelling or pain.

6.To discuss the staging and treatment of testicular cancer.

Cases

Case 1

A mother brought her 15-month-old son in for evaluation because he has “only one testicle.”

693

694 R.E. Weiss

Case 2

A 15-year-old boy presented to the emergency department with acute testis pain and nausea.

Case 3

A 24-year-old man presented to his physician with a “lump on his testis.”

Introduction

This chapter discusses the diagnosis and treatment of cryptorchidism, the acute scrotum, and testis cancer.

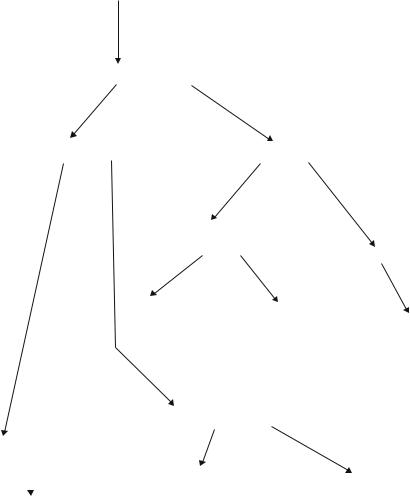

The testicle’s primary responsibility is to make sperm and testosterone. Testicular development and descent are controlled intricately by the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad axis (Fig. 39.1). The hypothalmus releases GNRH which stimulates the pituitary to release LH and FSH. LH and FSH stimulate the testis to grow and make testosterone. Testosterone regulates its own production by regaling feedback on the hypothalmus and pituitary. Testicular endocrine function becomes fully developed after puberty.

Descent of the testis and epididymis from the abdomen occurs only in mammals. Scrotal development in males is a result of the testis and epididymis descending, causing the skin to stretch. Sperm fertility is enhanced by being stored in a cooler region within the scrotum rather than in the abdomen. Cryptorchid or “undescended testis” results in infertility if the testis is not placed in the scrotum.

Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

Hypothalmus

GNRH |

(Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone) |

Pituitary

LH (Luteinizing Hormone)

FSH (Follicular Stimulating Hormone)

T (Testosterone)

Testis

Figure 39.1. Hypothalmic-pituitary-gonadal axis.

39. Scrotal Disorders 695

During early development, the testes originates in the abdomen near the kidney. During early embryologic development, the processus vaginalis is an invagination at the inguinal ring. The gubernaculum attaches superiorly onto the Wolffian duct and inferiorly into the inguinal canal. As the fetus matures, the testis descends into the scrotum. This descent from abdomen to scrotum explains why the testis lymphatic drainage is to the nodes below the renal hilum and the venous drainage is to the vena cava on the right and to the renal vein on the left.

Cryptorchidism

Cryptorchidism or undescended testis is defined as an abnormal descent of the testis and can be unilateral or bilateral. The incidence is 3.4% to 5.8% in full-term boys and 1.82% at 1 year of age. The testis can be found in the upper scrotum, inguinal canal, or abdomen. Two thirds of the cases are unilateral, while one third of the cases are bilateral. It is more common in premature boys.

For the examination, the child should be placed in the cross-legged position. Initial visual inspection should reveal a scrotum that is developed bilaterally. The testis should be palpated between the thumb and forefinger. The testes should have equivalent size and texture. The undescended testis may be retractile and easily manipulated into the scrotum. Often, slight groin pressure with the forefinger brings the testis down into the scrotum. If the testis is not palpated in the scrotum or groin, ultrasonography may be necessary to locate it above the internal inguinal ring or within the abdomen. Most retractile testes descend by 1 year of age.

If the testis does not appear to be descending properly, surgical orchiopexy is the necessary treatment to place the testis in the scrotum, which allows appropriate testis maturation and eventual fertility. Most surgeons perform this procedure by the time the patient has reached 1 year of age. Cryptorchid testis is associated with inguinal hernia in 25% of patients due to a patent processus vaginalis. The hernia should be repaired when the orchiopexy is performed. Orchiopexy usually is performed through an inguinal incision, allowing the surgeon to mobilize the testis and its blood supply to reach the scrotum. Associated hernias also can be repaired. The testis is sutured to the dartos in the scrotum to keep it in place.

Case Discussion

In the child in Case 1, there was no history of trauma or infection, and the mother stated that she had noted this condition for several months. The child was examined in a cross-legged position. The right testis was in a normal position within the scrotum; however, the left testis was in the groin, near the external ring, and could not be manipulated into the scrotum. The mother discussed the situation with the urologist and decided that her child should have an elective orchipexy.

696 R.E. Weiss

Scrotal Pain

Scrotal pain can be due to several etiologies that range from chronic to surgical emergency. The differential diagnosis for a painful testis includes testis torsion, epididymitis, trauma, tumor, torsion of appendix testis or appendix epididymis, incarcerated hernia, and ureteral calculi. See Algorithm 39.1. Occasionally, kidney stones that migrate to the distal ureter cause pain referred to the groin, but this pain usually is colicky in nature.

Testis Torsion

The patient who presents with acute testis pain should be treated as a surgical emergency. A patient who has a testis torsion and is not treated within 3 to 12 hours may suffer testis atrophy. Testis torsion occurs because the testis rotates or twists its blood supply, essentially strangling the testis. Vascular occlusion results in acute pain as the testis becomes edematous.

Testis torsion usually occurs in adolescent males, but it may be seen in cryptorchid testis or as a result of testis trauma. The cremasteric muscle spasms, causing the spermatic cord to rotate upon itself.

The patient’s history of torsion usually is consistent with sudden onset, acute pain, nausea, and vomiting. The patient should have a urinalysis, urine culture and sensitivity, and complete blood count

Acute testis pain |

|

|

|

||

|

Duration |

|

Differential |

||

|

|||||

|

|

||||

History and |

|

|

|

||

|

– Torsion of testis |

||||

Physical |

|

||||

|

|

|

– Epididymo-orchitis |

||

|

|

|

– Trauma |

||

|

|

|

– Hernia |

||

|

|

|

– Appendix |

||

|

|

|

– Torsion of Appendages |

||

Trauma: |

Scrotal |

||||

ultrasound |

|||||

– Conservative |

|

|

|

||

– Surgery if testis is ruptured or |

|

|

Conservative therapy |

||

tunica albuginea is violated |

|

|

|||

Hernia |

|||||

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

Surgery if incarcerated |

|

|

Epididymo-orchitis |

Torsion of testis |

|||

|

Antibiotic |

||||

|

– Surgical treatment |

||||

|

treatment |

||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Torsion of appendage |

|||

|

|

– Surgical or conservative management |

|||

Algorithm 39.1. Algorithm for workup of acute testis pain.

39. Scrotal Disorders 697

(CBC) to evaluate infectious sources consistent with epididymitis.

Physical examination of the patient with torsion reveals a tender, erythematous scrotum with a high or horizontal position of the testis.

The cremasteric reflex usually is absent. Epididymitis usually presents with gradual onset, white blood cells in the urine, and increased tenderness behind the testis along the epididymis. The patient may have a history of recent sexual activity or symptoms of urinary infection or prostatitis. Differentiating the two may be difficult. Epididymitis may progress to epididymo-orchitis.

Diagnosis should be confirmed with an emergency Doppler ultrasonography. A testis torsion appears as hypovascular, while epididymitis appears as hypervascular. Since Doppler ultrasonography technology has improved, nuclear scanning rarely is necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

For treatment, manual detorsion may be attempted if the torsion has occurred within a few hours. This consists of infiltration of the spermatic cord near the external ring with lidocaine. The left testis is rotated counterclockwise manually, while the right testis is rotated clockwise manually. Manual detorsion usually is not effective because of the patient’s degree of pain. Emergent surgical scrotal exploration should be performed under general anesthesia. A scrotal incision is made, the spermatic cord is untwisted, and the testis is inspected. If the testis appears viable, it should be sutured in place to the surrounding tissue. The contralateral testis also should undergo orchiopexy during the same procedure. Nonviable testis require orchiectomy.

Torsion of the testicular appendages may mimic testis torsion and usually occurs in boys younger than 16 years of age. The appendix testis (remnant of the Müllerian duct) and appendix epididymis (remnant of the Wolffian duct) may twist and cause venous engorgement and infarction, producing the “blue-dot sign.” These cases may be managed conservatively with pain medications. If the pain persists or there is concern of testis torsion, emergent surgical exploration should be performed.

Case Discussion

The patient in Case 2 stated that the pain occurred suddenly about 2 hours previously and continued to be unbearable. He denied trauma or sexual activity. Urinalysis was negative for white blood cells, and Doppler ultrasonography revealed decreased flow to the testis. The patient underwent emergent scrotal exploration in the operating room, where a testis torsion was found. The spermatic cord was untwisted, and the testis regained its pink color. The testis was sutured to surrounding tissue (orchipexy) to prevent future torsion and the contralateral testis also underwent orchiepexy. The patient recovered without problem.

Epididymo-orchitis

Acute epididymitis is extremely painful and may mimic the symptoms of testicular torsion. The incidence of epididymitis is much higher than that of testicular torsion. Acute epididymitis is an infectious process

698 R.E. Weiss

caused by reflux of bacteria via the vas deferens. It is caused by urinary tract pathogens, such as gram-negative organisms, and often originates from prostatitis or an indwelling urethral catheter. Acute epididymitis also can be associated with sexually transmitted diseases, such as those caused by Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhea. The patient usually presents with gradual onset of pain. Acute onset, however, may occur and mimic testis torsion. The patient complains of tenderness, scrotal erythema, and fever.

Laboratory findings reveal white blood cells in the urine and a positive Gram stain. The CBC shows an elevated white cell count, with a shift to the left. Ultrasonography reveals a hypervascular area consistent with the inflammatory response of infection.

Treatment should include immediate antibiotics. If a urinary pathogen is suspected, the patient should be given a quinolone or a trimethoprim sulfate until urine and blood culture sensitivities return. If a sexually transmitted disease is suspected, the patient should be given an injection of ceftriaxone followed by oral doxycycline or tetracycline. Depending on the severity of the infection, the patient may need pain medications, ice packs to the scrotum, and bed rest.

The pain may not resolve for 2 weeks or longer. The patient should be followed closely for possible abscess. Infertility may be a long-term sequela. Some patients progress to chronic epididymitis and require long-term antibiotic coverage and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication.

Testis Masses

Testis masses include benign lesions of the scrotum and testis tumors. See Algorithm 39.2.

Benign Lesions of the Scrotum

Hydrocele

Hydroceles are a common scrotal problem. They usually are benign, but they must be differentiated from testis tumors and inguinal hernias.

Hydroceles in children usually are due to persistent patency of the processus vaginalis. The processus usually closes, and the hydrocele resolves. Persistent hydroceles after the age of 2 years usually are repaired surgically.

Hydroceles in adults usually are due to fluid collection within the tunica vaginalis. They often are due to nonspecific epididymitis or orchitis or are a result of scrotal trauma. Occasionally, they can be related to testis cancer, tubercular epididymitis, or radiotherapy.

Physical examination of the hydrocele reveals a uniformly enlarged mass in the scrotum. It usually is nontender and can be transilluminated. Ultrasonography confirms the diagnosis of hydrocele and rules out the presence of testis tumor or inguinal hernia.

Treatment of a hydrocele depends on the symptoms. If the hydrocele is small and the patient has no discomfort, the patient is managed conservatively. If the hydrocele is large, it should be explored

39. Scrotal Disorders 699

Testis mass

|

|

|

|

|

Differential |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

History and physical |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

–Testis tumor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

–Varicocele |

|

|

|

|

|

|

–Spermatocele |

|

|

|

|

|

|

–Hydrocele |

|

|

|

|

|

|

–Tunica albuginea cyst |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scrotal ultrasound |

||

|

|

|

|

Varicocele |

||

|

|

|

|

– Conservative |

||

Testis |

|

|

– Surgery for pain |

|||

|

|

or infertility |

||||

Tumor |

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

||

(see Algorithm |

|

|

Spermatocele |

|||

39.3) |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

–Conservative |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

–Surgery for pain |

||

Hydrocele |

|

Tunica cyst |

||||

|

||||||

|

|

–Conservative |

||||

–Conservative

–Surgery for large size

Algorithm 39.2. Algorithm for workup of testis mass.

surgically, and the tunica vaginalis should be resected. Simple aspiration of the fluid often results in recurrence or infection.

Spermatocele

Spermatocele is another common benign mass. It usually is small, with the patient complaining of a nontender, firm testis mass. The spermatocele is located in the epididymis, posterior to the testis and clearly separate. The spermatocele is caused by obstruction of the tubules connecting the rete testis to the head of the epididymis. The cystic nature of the spermatocele should be confirmed by ultrasonography. Initial treatment should be conservative. If the patient complains of persistent pain over a period of time, surgical excision may be performed.

Varicocele

A varicocele is the dilation of the pampiniform venous plexus, which drains the testis. Varicoceles probably are due to incompetence of venous valves. The higher prevalence of left varicoceles may be caused by the insertion of the left spermatic vein on the left renal vein. Approximately 20% of men have varicoceles, and they usually are benign. In a small number of men, these veins become painful, especially when standing upright for long periods of time. Rapid onset of

700 R.E. Weiss

a varicocele in an older man may be an indication of a renal tumor obstructing the spermatic vein. Large varicoceles also have been associated with infertility. Varicoceles may affect the temperature of the testes and subsequently alter sperm count, sperm motility, and morphology.

Physical examination of men with varicoceles should be performed with the patient in the upright position. The engorged veins can be palpated superior to the testis following the path of the spermatic cord. These veins usually dilate when the patient performs the Valsalva maneuver and empty when the patient is in the reclining position. Testicular size should be compared to the contralateral side.

Most men with varicoceles do not need treatment. Surgery may become necessary if the patient demonstrates diminished testicular size or abnormal sperm parameters or if the patient complains of persistent pain. Surgery may be performed by high ligation of the spermatic veins in the abdomen or ligation of the branches of inferior veins in the spermatic cord. It is important to identify all collaterals to prevent recurrence.

Testis Tumors

Testis tumors commonly occur in young men between the ages of 20 and 40 years old. There are two to three new cases of testis cancer per 100,000 men in the United States per year. Only 1% to 2% of these cases occur bilaterally. Six percent of men with testis cancer have a history of cryptorchidism. Testis tumors tend to occur in an age group of men who often do not have routine physical examinations. Therefore, patient awareness and self-examination are very important. Early detection is essential, as the cure rate is high. Due to improvements of chemotherapy, the 5-year survival rate exceeds 90%. See Algorithm

39.3.

Testis tumors can be divided into two groups: seminoma and nonseminoma. Seminoma represents 35% of testis tumors. Nonseminomatous tumors include embryonal carcinoma (20%), teratoma (5%), choriocarcinoma (<1%), and mixed teratocarcinoma (40%). Serum tumor markers for testis cancer are b-human chorionic gonadotropin (b-HCG), a-fetoprotein (AFP), and lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH).

These serum markers should be drawn if testis cancer is suspected. b- Human chorionic gonadotropin is present in 5% to 10% of men with seminoma, in 40% to 60% of men with embryonal carcinoma, and in all men with choriocarcinoma. It is made by syncytiotrophoblasts and can be used to follow the tumor’s response to therapy. It has a half-life of 24 hours. a-Fetoprotein is produced by the yolk sac. It is found primarily in pure embryonal carcinoma, in mixed (teratocarcinoma), and in yolk sac tumors, but it is never elevated in seminoma or pure choriocarcinoma. The half-life of AFP is 5 days. Lactic acid dehydrogenase is a less specific tumor marker that may be elevated in patients with metastatic disease.

Patients present with a palpable mass in their testis. Delay in diagnosis often occurs because young patients do not present immediately

39. Scrotal Disorders 701

Testis tumor

check serum b-HCG, AFP, LOH

Radical orchiectomy

Nonseminoma |

|

|

Seminoma |

||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

Chest X-ray |

||

|

|

|

CT scan of |

|

|

|

|

abdomen and pelvis |

|||

Chest X-ray |

No metastatic |

||||

disease |

|||||

CT scan of |

|

|

|

|

Metastatic disease |

abdomen |

|

|

|

|

|

and pelvis |

|

|

|

|

|

Prophylactic |

|

|

Surveillance |

||

radiation |

|

|

|

|

Chemotherapy |

|

|

No metastatic disease |

|

Metastatic disease |

|

|

|

|

|

Retroperitonal |

Surveillance |

|

|

||

|

|

lymph node |

|

Chemotherapy |

|

||

dissection |

|

||

Algorithm 39.3. Algorithm for workup of testis tumor. AFP, a-fetoprotein; b-HCG, b-human chorionic gonadotropin; CT, computed tomography; CXR, chest x-ray; LDH, lactic acid dehydrogenase.

to their physicians or because they are mistakenly diagnosed as having epididymitis. Physical examination and scrotal ultrasonography are essential in order to make the diagnosis. For patients with indeterminate lesions, magnetic resonance imaging may assist in the evaluation.

Testis cancer is treated by radical orchiectomy. An incision is made in the groin. The spermatic artery and vein are clamped to avoid tumor spread, and the testis is removed along with the spermatic cord. Sites of metastases include the retroperitonem and the lung. Therefore, staging includes abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan and chest x-ray. Testis tumors on the right tend to metastasize to the interaortocaval area at the level of the renal hilum (following the drainage of the right spermatic vein) and on the left to the periaor-

702 R.E. Weiss

tic area at the left renal hilum (following the drainage of the left spermatic vein). Once the testis tumors metastasize to these “primary landing sites,” they tend to progress in a stepwise manner to other lymph nodes in the retroperitoneum. Disease also may progress to the lung, liver, and brain. Choriocarcinoma, however, may spread initally to the lung. See Table 39.1 for the TNM staging stystem for testis cancer.

After the orchiectomy is performed, markers should decline and eventually normalize. If they remain elevated, residual disease is present. Seminoma is very radiosensitive. Patients with no disease or minimal retroperitoneal disease are advised to have radiation to the retroperitoneum as prophylaxis or treatment. Patients with higher stage disease are given chemotherapy: etoposide and platinol (cisplatin) (EP) or bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP).

Patients with nonseminomatous tumors eventually should have normal serum markers after orchiectomy if there is no metastatic disease. Patients with gross mestastases or persistently positive markers are given chemotherapy (EP or BEP). Patients who have normal markers and no gross evidence of disease have an approximately 25% to 40% possibility of relapse, depending on the pathology. Because of this, they are advised to undergo a retroperitoneal lymph node dissection. This procedure requires an abdominal incision, and lymph nodes are removed below the renal hilum and along the vena cava or aorta, depending on the side of the testis tumor and the suspected landing site. Side effects of the surgery may include impairment of ejaculatory function (retrograde), which may result in infertility. Some patients opt not to have the surgery and require intensive surveillance with frequent CT scans in order to identify metastatic disease.

Table 39.1. TNM staging system for testis cancer.

T: Primary tumor

Tx |

Cannot be assessed |

T0 |

No evidence of primary tumor |

Tis |

Intratubular cancer (CIS) |

T1 |

Limited to testis and epididymis, no vascular invasion |

T2 |

Limited to testis and epididymis with vascular invasion or invades |

|

into tunica vaginalis |

T3 |

Invades spermatic cord |

T4 |

Invades scrotum |

N: Regional lymph nodes |

|

Nx |

Cannot be assessed |

N0 |

No regional lymph node metastasis |

N1 |

Metastasis in a lymph node mass 2 cm or less |

N2 |

Metastasis in a lymph node mass >2 cm and <5 cm or multiple |

|

nodes none >5 cm |

N3 |

Metastasis in lymph node mass >5 cm |

M: Distant metastasis |

|

Mx |

Cannot be assessed |

M0 |

No distant metastasis |

M1 |

Distant metastasis present |

Source: Reprinted from Presti JC Jr. Urology. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001, with permission.

39. Scrotal Disorders 703

Patients who develop recurrence have an excellent response to BEP.

Testis tumors are one of the few tumors for which long-term cures have been achieved with chemotherapy.

Case Discussion

The patient in Case 3 denied trauma or pain. The physician examined the patient and found a firm nodule on the testis that did not transilluminate. The physician ordered serum b-HCG, AFP, and LDH tests and a scrotal ultrasound. The ultrasound revealed a solid left testis mass and the serum markers showed an elevated AFP level, but normal b-HCG and LDH levels. The patient underwent a left radical orchiectomy through an inguinal incision. Three weeks after the surgery, the AFP level returned to normal, and the patient’s chest x-ray and abdominal CT scan showed no evidence of metastatic disease. The patient will undergo a surgical retroperitoneal lymph node dissection to determine if he has metastatic disease in the retroperitoneum.

Summary

This chapter discussed the diagnosis and management of the undescended testis, and the evaluation and management of the acute scrotum. Testis torsion must be diagnosed promptly so that the proper surgery can be performed to salvage the testis.

There are several benign etiologies for scrotal masses including hydroceles, varicoceles, and spermatoceles. Testis tumors occur in young men and must be diagnosed early for proper treatment. Ultrasonography provides the best diagnostic test to differentiate benign from malignant lesions of the testis.

Selected Readings

Albanese CT. Pediatric surgery. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: SpringerVerlag, 2001.

Berkowitz GS, Lapinski RH, Dolgin SE, Gonzella JG, Bodian CA, Holzman IR. Prevalence and natural history of cryptorchism. Pediatrics 1993;92:44–49.

Carroll PR, Presti JC, eds. Testis cancer. Urol Clin North Am 1998;365–531. Cuckow PM, Frank JD. Torsion of the testis. Br J Urol 2000;86(3):349–353. Dearnaley DP, Huddart RA, Horwich A. Managing testis cancer. Br Med J

2001;322(7302):1583–1588.

Foster RS, Donahue JP. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for the management of clinical stage I non-seminoma. J Urol 2000;163(6):1788–1792.

Jefferson RH, Perez LM, Joseph DM. Critical analysis of the clinical presentation of the acute scrotum: 9-year experience at a single institution. J Urol 1997;158(3):1198–1200.

King LR. Undescended testis. JAMA 1996;276(11):856.

Noske HD, Kraus SW, Altinkilic BM, Weidner W. Historical milestones regarding torsion of scrotal organs. J Urol 1998;159(1):13–16.

Oliver RTD. Current opinion in germ cell cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 2000;12(3):249–254.

704 R.E. Weiss

Presti JC Jr. Urology. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001.

Rozanski TA, Bloom DA. The undescended testis: theory and management. Urol Clin North Am 1995;22(1):107–118.

Schmoll HJ. Treatment of testicular tumors based on risk factors. Curr Opin Urol 1999;9(5):431–438.