- •Preface

- •Content

- •Contributors

- •2 Practicing Evidence-Based Surgery

- •5 Surgical Critical Care

- •7 Shock

- •8 Surgical Bleeding and Hemostasis

- •11 Head and Neck Lesions

- •16 Acute and Chronic Chest Pain

- •17 Stroke

- •18 Surgical Hypertension

- •19 Breast Disease

- •20 Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •21 Abdominal Pain

- •23 Abdominal Masses: Vascular

- •24 Jaundice

- •25 Colon and Rectum

- •26 Perianal Complaints

- •28 The Ischemic Lower Extremity

- •29 The Swollen Leg

- •30 Skin and Soft Tissues

- •31 Trauma Fundamentals

- •33 Musculoskeletal Injuries

- •34 Burns

- •36 Neonatal Intestinal Obstruction

- •37 Lower Urinary Tract Disorders

- •38 Evaluation of Flank Pain

- •39 Scrotal Disorders

- •40 Transplantation of the Kidney

- •41 Transplantation of the Pancreas

- •42 Transplantation of the Liver

- •Index

25

Colon and Rectum

Stephen F. Lowry and Theodore E. Eisenstat

Objectives

1.To describe the presentation and potential complications of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

2.To contrast the pathology, anatomic location and pattern, cancer risk, and diagnostic evaluation of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

3.To discuss the role of surgery in the treatment of patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

4.To outline the diagnosis and management of colonic volvulus and diverticular disease.

5.To outline the treatment of carcinoma located at different levels of the colon and rectum.

Cases

Case 1

A 35-year-old Caucasian man presents with a 48-hour history of bloody diarrhea, diffuse abdominal pain, and feverishness. He experienced some blood in his stools 6 months previously, but he did not seek medical attention. His temperature is 102°F and his white blood count (WBC) is 20,000 cm2. Rectal exam shows gross blood and mucus in the stool. Physical exam reveals abdominal distention, slight rebound tenderness diffusely, and hyperactive bowel sounds. Aside from evidence of dehydration, there are no other significant findings. An abdominal series reveals diffusely dilated large bowel with no evidence of obstruction.

Case 2

A 60-year-old man presents with a 12-hour history of persistent bright red blood per rectum. Aside from a weight loss of 5 pounds over

446

25. Colon and Rectum 447

the prior 2 months, he has been healthy with no significant medical history. His blood pressure is 100/50 (supine), and his pulse is 100 beats per minute. A hematocrit reading is 28%. Abdominal exam reveals no masses or tenderness. Radiographs of the chest and abdomen are unrevealing.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Colon and Rectum

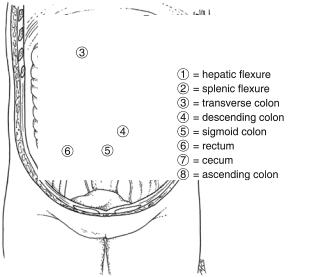

The colon is one structural unit with two embryologic origins. The cecum, right colon, and midtransverse colon are of midgut origin and as such are supplied by the superior mesenteric artery. The distal transverse colon, splenic flexure, descending colon, and sigmoid colon are of hindgut origin and receive blood from the inferior mesenteric artery. The transverse and sigmoid colons are completely covered with peritoneum and are attached by long mesenteries, allowing for great variation in the location of these structures (Fig. 25.1).

The blood supply to the colon is quite variable, but general patterns exist (Fig. 25.2). The venous drainage (Fig. 25.3) of the colon is through veins that bear the same name as the arteries with which they run except for the inferior mesenteric vein.

Small numbers of lymphatics actually exist in the lamina propria, but, for practical purposes, lymphatic drainage and therefore, the

Figure 25.1. The posterior aspects of the ascending and descending colon are “extraperitoneal,” as those surfaces are not covered with peritoneum, whereas the transverse and sigmoid colon are completely intraperitoneal, as these segments are completely peritonealized and on mesenteries. (Reprinted from Schecter WP. Peritoneum and Acute Abdomen. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001, with permission.)

448 S.F. Lowry and T.E. Eisenstat

Figure 25.2. The arterial supply to the colon and rectum. The lymphatic drainage parallels the arterial supply. (Reprinted from Schecter WP. Peritoneum and Acute Abdomen. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001, with permission.)

ability of malignancies to metastasize, begin once the tumor has invaded through the muscularis mucosa. The extramural lymphatic vessels and nodes follow along the arteries to their origins at the superior and inferior mesenteric vessels. The colon is innervated via the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Sympathetic stimulation inhibits peristalsis, whereas it is promoted by the parasympathetic system.

The major functions of the colon are absorption, storage, propulsion, and digestion of the output of the proximal intestinal tract. Absorption of the salts and water of the ileal output is critical in the maintenance of normal fluid and electrolyte balance. It is regulated through a complex, integrated, neurohormonal pathway in normal individuals; the ileum expels approximately 1500 mL of fluid per day, of which 1350 mL is absorbed by the colon.

The rectum is approximately 12 to 15 cm long. It extends from the rectosigmoid junction, marked by the fusion of the taenia, to the anal canal, marked by the passage of the bowel into the pelvic floor musculature. The rectum lies in the hollow of the sacrum and forms three distinct curves, creating folds that, when visualized endoscopically, are known as the valves of Houston.

See Algorithm 25.1 for the initial workup of large-bowel disease.

25. Colon and Rectum 449

Figure 25.3. The venous drainage of the colon and rectum. (Reprinted from Schecter WP. Peritoneum and Acute Abdomen. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001, with permission.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Physical exam |

Indicated |

||||||||||

|

History |

Intensity and |

|

Diagnostic tests: |

|

|

|

|

includes |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

radiology, endoscopy, etc., |

location of |

operation |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

includes: |

|

|

nature of pain |

|

suggest |

|

|

|

|

|

pain |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prior |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ischemia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

Acute |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Peritoneal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emergency, |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

signs |

|

|

|

|

|

immediate |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perforation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Illnesses: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GI, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Complete |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Obstruction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

other |

|

|

|

Chronic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Partial |

|

Urgent |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Bleeding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inflammation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

None |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mass |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Elective |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Therapies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Malignancy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

medications |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Algorithm 25.1. Algorithm for the initial workup of large-bowel disease.

450 S.F. Lowry and T.E. Eisenstat

Benign Diseases

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Crohn’s Disease

The etiology of Crohn’s disease remains elusive, as does the etiology of ulcerative colitis with which it shares many similarities. The presentation of Crohn’s disease can be difficult to appreciate. Patients have a variety of symptoms that are directly related to the extent, character, and location of the inflammation. The classic symptoms are abdominal pain, diarrhea (which can be bloody), and weight loss. Other signs and symptoms include fever, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, palpable abdominal mass, aphthous ulcerations of the mouth, cholelithiasis, and renal calculi.

The nature of Crohn’s disease can be divided into three categories: inflammatory, stricturing, and fistulizing. Patients with stricturing Crohn’s disease may have only symptoms of obstruction, whereas those with a fistula or abscess may have a more septic presentation. Patients with an inflammatory presentation may have symptoms of malabsorption with its sequelae.

The evaluation for Crohn’s disease verifies the diagnosis and assesses the severity and extent of the disease. Upper and lower endoscopy with directed and random biopsies and radiographic imaging help to elucidate the diagnosis. Stool cultures may find evidence of infectious enterocolitis that may mimic Crohn’s disease. Colonoscopy is the most sensitive test for identifying a patchy distribution of inflammation, terminal ileal involvement, and rectal sparing that are highly suggestive of Crohn’s. Endoscopic findings include mucosal edema and erythema, aphthous or linear ulcerations, and fibrotic strictures.

Many patients with colonic disease also have small-bowel findings, which distinguishes Crohn’s from ulcerative colitis. To evaluate the extent of the disease, an upper gastrointestinal (GI) examination with small-bowel follow-through is imperative to find lesions of the stomach, duodenum, or small intestine such as strictures or fistulas.

The most common symptoms found outside the GI tract involve the skin, eyes, and joints. Multiple subcutaneous nodules that are tender, red, raised, and microscopically composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes characterize erythematous lesions that may form a tender necrotizing ulcer. Most of these occur in the pretibial area, but they also can occur anywhere on the body. Ocular manifestations include uveitis, iritis, episcleritis, vasculitis, and conjunctivitis. These findings are associated more commonly with colonic disease and infrequently precede any intestinal symptoms.

The incidence of carcinoma is increased in the setting of Crohn’s disease and should be suspected in patients with a severe or chronic stricture.

Medical Therapy: The primary treatment of Crohn’s disease is medical. Surgery is indicated for complications of the disease process.

25. Colon and Rectum 451

Sulfasalazine and mesalamine are the two aminosalicylates used for Crohn’s disease. For patients with exacerbations leading to moderate or severe Crohn’s disease, steroids are the primary therapy.

As increasing evidence points to an immunologic etiology of inflammatory bowel disease, efforts have been made to utilize various immunotherapies. The drugs most commonly used are azathioprine and its metabolite, 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP). Methotrexate is a folate analogue that inhibits purine and pyrimidine synthesis and has been shown in a number of trials to be effective in treating Crohn’s disease. However, this drug has significant side effects including hepatotoxicity and bone marrow suppression and thus is reserved for patients with severe Crohn’s that is refractory to other therapies. Recently, anti–a- tumor necrosis factor (a-TNF) monoclonal antibody has been proven to be useful in the management of Crohn’s disease.

Surgical Therapy: As previously noted, the primary treatment of

Crohn’s disease is medical, and surgery is considered for patients with specific complications of the disease. See Algorithm 25.2. Crohn’s disease cannot be cured by an operation, but surgery can help ameliorate certain situations (Table 25.1).

Small intestinal or ileocolic stenotic disease is treated by resection with primary anastomosis. Only grossly involved intestine should be resected, because wide resection or microscopically negative margins of resection have no impact on the recurrence rate of the

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Small-bowel |

|

|

|

|

|

Bypass |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

disease |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stricturoplasty |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Indications for surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total proctocolectomy with |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

• Failed medical therapy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ileostomy |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

• Obstruction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

• Complicated fistulas |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abdominal colectomy with |

||

|

|

|

Colonic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

• Perforation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ileorectal anastomosis |

|||||

|

|

|

disease |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

• Cancer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

• Hemorrhage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Subtotal colectomy with |

||

• Abscess |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ileostomy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Segmental resection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abscess drainage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fistulotomy |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

disease |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Seton |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Algorithm 25.2. Algorithm for the management of Crohn’s disease.

452 S.F. Lowry and T.E. Eisenstat

Table 25.1. Indications for surgical treatment of Crohn’s disease.

Failure of medical treatment

Persistence of symptoms despite corticosteroid therapy for longer than 6 months

Recurrence of symptoms when high-dose corticosteroids tapered Worsening symptoms or new onset of complications with maximal

medical therapy

Occurrence of steroid-induced complications (cushingoid features, cataracts, glaucoma, systemic hypertension, aseptic necrosis of the head of the femur, myopathy, or vertebral body fractures)

Obstruction

Intestinal obstruction (partial or complete) Septic complications

Inflammatory mass or abscess (intraabdominal, pelvic, perineal) Fistula if

Drainage causes personal embarrassment (e.g., enterocutaneous, enterovaginal fistula, fistula in ano)

Fistula communicates with the genitourinary system (e.g., enteroor colovesical fistula)

Fistula produces functional or anatomic bypass of a major segment of intestine with consequent malabsorption and/or profuse diarrhea (e.g., duodenocolic or enterorectosigmoid fistula)

Free perforation Hemorrhage Carcinoma

Growth retardation

Fulminant colitis with or without toxic megacolon

Source: Reprinted from Michelassi F, Milsom J. Operative Strategies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1999.

disease. It may lead to additional complications, such as short bowel syndrome.

Patients who present with fistulizing disease with either established fistulas or undrained sepsis require the greatest amount of judgment and caution. The surgical inclination is to operate urgently. However, percutaneous drainage, parenteral nutrition, and bowel rest usually control sepsis and allow the inflammation of the uninvolved bowel and surrounding structures to resolve.

For isolated Crohn’s colitis, a total proctocolectomy with ileostomy or total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis or ileostomy and rectal stump are the primary therapies.

The manifestations of perianal Crohn’s disease are multiple, including abscesses, fistulas, fissures, ulcers, strictures, and incontinence. Perianal disease is the first presentation of Crohn’s disease in 8% of cases. Estimates of the number of Crohn’s patients who develop perianal manifestations at some time range from 10% to 80%. As with Crohn’s disease proximally, palliation of symptoms and preservation of functional bowel are the priorities guiding surgical intervention. Likewise, the aim of therapy is the treatment of complications of disease rather than the disease itself. Two mandates clarify these principles with respect to perianal disease: (1) the management of a septic focus is an indication for surgery, and (2) the sphincter should be preserved as long as the patient is coping well. As painful as Crohn’s per-

25. Colon and Rectum 453

ineal lesions often appear, they surprisingly are well tolerated. In fact, the complaint of pain is indicative of an abscess, and surgical consultation should be arranged promptly.

Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a mucosal inflammatory condition of the GI tract confined to the colon and rectum. Like Crohn’s, it is considered a manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), as discussed in Case 1. Although the medical therapy is similar for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, the surgical therapies for each differ greatly, and it is imperative that a clear diagnosis is made whenever possible.

The clinical manifestations of ulcerative colitis vary with the severity of the disease. Patients may have active disease with intervening periods of quiescence. The most common symptom of ulcerative colitis is bloody diarrhea. Patients with mild disease may have occasional blood and mucus and a moderate number of stools. Frequent, explosive diarrhea with significant bleeding or discharge of mucus and pus manifests more severe disease. Massive hemorrhage from ulcerative colitis is rare. Severe disease also may be associated with fever, abdominal pain, tenesmus, malaise, anemia, or weight loss. Some may have fecal incontinence with severe disease activity.

Most patients present with mild to moderate disease involving the rectum and a contiguous segment of the distal colon. About 20% of patients present with pancolitis. The so-called toxic “megacolon” is a presentation of fulminant colitis with fever, abdominal pain, and leukocytosis that may or may not be associated with radiographic evidence of colonic dilatation. As presented in Case 1, patients may require emergent operation for perforation or resistance to medical therapy.

The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis is made endoscopically. A sigmoidoscopy may be diagnostic, and colonoscopy is hazardous (perforation) when active disease is present. Enemas should not be given before the exam for the same reasons. Surveillance by colonoscopy in ulcerative colitis is important because of the increased risk of colorectal dysplasia and carcinoma. Patients at higher risk are those with colitis proximal to the splenic flexure and those with long-standing disease, at least 8 to 10 years.

The extraintestinal manifestations of ulcerative colitis are similar to those of Crohn’s disease, with the exception of hepatobiliary complications, which are more common and can be quite severe. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is uncommon with Crohn’s disease and occurs in 7.5% of patients with UC. The only cure for this disease is liver transplant.

Medical Therapy: The medical therapy for ulcerative colitis overlaps significantly with those therapies used for Crohn’s disease, discussed earlier. Sulfasalazine, as well as preparations that delay the release of the active ingredient [5-acetylsalicylic acid (5-ASA)], are more useful in treating ulcerative colitis. Drugs to treat the presumed immune basis for UC also may be useful.

454 S.F. Lowry and T.E. Eisenstat

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consider for |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hemorrhage |

Abdominal |

|

|

sphincter |

|||

Indications for |

|

|

|

|

|

Perforation |

|

|

preservation |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

colectomy with |

|

|

||||||

urgent surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

at a later date |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

Toxic colitis |

ileostomy |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

when health |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Megacolon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

has been restored |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total proctocolectomy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Refractory to medical Rx |

|

|

|

|

|

|

and Brook ileostomy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Poor sphincter |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Steroid dependent |

function |

|

|

Subtotal colectomy with |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

Indications for |

|

|

|

|

|

Stricture |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Brook ileostomy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

elective surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

Dysplasia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(later proctectomy) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intolerable side effects |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adbominal colectomy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

of medication |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adequate sphincter |

|

|

|

with ileorectal |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Failure to thrive |

|

|

|

anastomosis |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

function |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

High cancer risk |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Colectomy, proctectomy, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ileopouch—anal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

anastomosis, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

temporary ileostomy |

Algorithm 25.3. Algorithm for the management of ulcerative colitis.

Surgical Therapy: Approximately 30% of all patients with ulcerative colitis ultimately have surgery. (See Algorithm 25.3.) The surgical therapy employed most often involves removing the colon and, in most cases, the rectum. For patients with chronic active or quiescent disease, the indications for surgery include an inability to wean from steroids, extracolonic manifestations that may respond to colectomy, and the presence of dysplasia or carcinoma on colonoscopy screening. Children with UC may require surgery to treat delayed growth and maturation secondary to medical therapy or malnutrition.

The ileal pouch–anal anastomosis has become the standard operation for ulcerative colitis. The advantage of the procedure is that it allows the patient to void per anus, thus avoiding a stoma. The disadvantages are that the procedure is associated with significant morbidity and that the risk of cancer is not completely eliminated, as it is when a standard proctocolectomy is performed.

Diverticular Disease

Diverticulosis: Diverticulosis is common. As the incidence of diverticulosis increases with age, the risk of complications, other than bleeding, does not increase. In fact, the risk of complications related to perforation may be higher in the younger age groups. Medical treatment is less effective for recurrent attacks, and complications associated with an acute attack increase from 23% for the first attack to 58% after more than one attack. Complications requiring surgery occur only

25. Colon and Rectum 455

in approximately 1% of patients with the disease, whereas nearly one third of symptomatic patients may require surgery at some point.

Colonoscopy is preferred over barium enema in the initial workup of suspected diverticular disease because of its superior sensitivity and specificity. However, colonoscopy is less rewarding and more dangerous in the evaluation of acute complications of perforated diverticular disease.

Fiber is the mainstay of the medical management of uncomplicated diverticulosis or mild diverticulitis. A high-fiber diet is believed to reduce intracolonic pressures, presumably eliminating the “cause” of diverticular disease.

Complications of colonic diverticula that may require surgical consultation or intervention are hemorrhage and the complications of perforation of a diverticulum, which include chronic left lower quadrant pain, phlegm, abscess, peritonitis, fistula, and stricture. Hemorrhage occurs in up to 20% of patients with diverticulosis. In 5%, the hemorrhage is massive. The source of the bleeding is generally right sided, even though the diverticula predominantly are present on the left. The majority of patients (70–82%) stop bleeding; up to one third continue to bleed and require intervention.

Once resuscitation is under way, attention is directed toward localization of the source. If the nasogastric tube and proctosigmoidoscopic evaluation suggest a distal source, a nuclear medicine test is the preferred first step. Angiographic localization is attempted in those with a positive nuclear medicine scan. Embolization or Pitressin infusion following angiography may control bleeding.

Diverticulitis: Diverticulitis develops when a diverticulum ruptures. In most cases, the perforation is microscopic, causing localized inflammation in the colonic wall or paracolic tissues. In more severe cases, an abscess may form or the diverticulum freely may rupture into the peritoneal cavity, causing generalized peritonitis. The average age at presentation is the early 60s; more than 90% of cases occur after 50 years of age.

Patients with acute diverticulitis typically present with the gradual onset of left lower quadrant pain and low-grade fever. The pain is constant and does not radiate. On physical examination, tenderness to palpation usually is present in the left lower quadrant or suprapubic region. A mass suggestive of a peridiverticular abscess or phlegmon also may be palpable. Rectal examination may reveal a boggy mass anteriorly if a pelvic abscess is present. Unlike diverticulosis, acute diverticulitis usually is not associated with hemorrhage, but 30% to 40% of cases have guaiac-positive stool.

Plain-film abdominal series including an upright chest x-ray should be obtained to rule out free intraperitoneal air or lower lobe pneumonia. These studies may be normal or may demonstrate a distal largebowel obstruction, localized ileus, or extracolonic air. Computed tomography with IV, oral, and rectal contrast is the study of choice (Fig. 25.4). Endoscopy generally is contraindicated in the setting of acute diverticulitis.

456 S.F. Lowry and T.E. Eisenstat

Figure 25.4. Computed tomography (CT) scan of a patient with acute diverticulitis. Note the “streaking” of the fat characteristic of inflammation and the thickening of the sigmoid colon bowel wall. (Reprinted from Schecter WP. Peritoneum and Acute Abdomen. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001, with permission.)

Mild cases of acute diverticulitis in immunocompetent patients can be managed on an outpatient basis with clear liquids and oral antibiotics. Ideal patients for outpatient management are those who are able to tolerate a diet, have no systemic symptoms or peritoneal signs, and are reliable. Immunocompromise, steroid therapy, and advanced age are contraindications to outpatient therapy (see Algorithm 25.4).

Purulent or fecal peritonitis may develop secondary to rupture of a contained abscess or free perforation of a diverticulum. Most present with an acute abdomen and some degree of septic shock. Aggressive intravenous resuscitation, antibiotics, and surgery are required for patients who present in this fashion. The presentation in the immunosuppressed population may not be as clear, and abdominal films and a computed tomography (CT) scan may be necessary to make the diagnosis. Nonetheless, the treatment is the same. They are explored urgently, and a resection with descending colostomy and oversewing of the rectal stump is performed in all but the sickest patients.

Fistulas develop in only 2% of patients with diverticulitis, but fistula is the indication for surgery in 20% of those undergoing surgery for diverticulitis and its associated complications (Fig. 25.5). The bladder is affected most commonly, with nearly two thirds of all patients in one series having colovesical fistulas. Such patients may present with pneumaturia, fecaluria, abdominal pain, urinary symptoms (frequency, urgency, dysuria), hematuria, and fever and chills. Colovaginal fistulas, the next most common diverticular fistula, present with vaginal discharge, air, or stool per vagina.

The indications for surgery for diverticulitis are recurrent attacks, a severe attack, age less than 50 years, immunocompromised patients, or a severe complication of perforation such as significant

25. Colon and Rectum 457

Acute diverticulitis

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

is diagnosed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

Systemic or peritoneal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symptoms are mild, |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

no systemic or peritoneal |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

signs are present |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

signs are present |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inpatient therapy: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Consider outpatient |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NPO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

treatment: |

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IV antibiotics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

clear liquids |

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hydration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

oral antibiotics |

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

±NGT decompression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Follow-up 48–72 hrs |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reassess during initial |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reassess at 48–72 hours |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

resuscitation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not Improved |

|

|

|

Improved |

|||||||||

|

|

Emergency surgery is |

|

Emergency surgery is not |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

indicated: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

indicated |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

Diffuse peritonitis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Continue treatment |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

Free air on plain film |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Medical management: |

|

|

|

|

10–14 d antibiotics |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NPO |

|

|

|

|

|

Advance diet when ready |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IV antibiotics |

|

|

F/U with surgeon and PMD |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Indication for surgery |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

hydration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

uncertain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

±NGT decompression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reassess at 48–72 hours |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not Improved |

Improved |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Imaging: CT or |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Continue treatment |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

hypaque enema |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10–14 d antibiotics |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Diverticulitis |

|

|

|

|

|

Advance diet when ready |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

Emergency |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

F/U with surgeon and PMD |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

not seen |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

surgery is |

|

|

Simple |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

indicated: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reevaluate |

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Free air |

|

|

abscess |

|

|

|

|

|

|

diagnosis and |

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

Complex abscess |

|

|

|

|

|

Large |

|

|

treatment |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

or phlegmon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Necrotic bowel |

|

|

|

Small |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

Surgery is not |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

Resuscitate and prepare |

|

Consider percutaneous |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

indicated |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

drainage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

for surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trial of medical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Surgery |

|

|

Return to medical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

management |

|

|

|

|

management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Algorithm 25.4. Algorithm for the management of acute diverticulitis. NGT, nasogastric tube; PMD, primary medical doctor. (Reprinted from Schecter WP. Peritoneum and Acute Abdomen. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001, with permission.)

458 S.F. Lowry and T.E. Eisenstat

Figure 25.5. CT scan of a patient with a fistula to the bladder. Note the air collection outside the colon that can be traced down to the bladder on serial images. Air in the bladder without a history of recent catheterization is diagnostic of a communication with the gastrointestinal tract. (Reprinted from Schecter WP. Peritoneum and Acute Abdomen. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001, with permission.)

25. Colon and Rectum 459

phlegmon/abscess, peritonitis, fistula, or stricture. The goals of surgical therapy are to minimize morbidity and mortality, remove the septic focus and diseased colon, avoid or at least minimize the risks of a second operation, and convert an emergent situation to an urgent or elective operation.

Infectious Colitides

Infections of the large bowel usually cause diarrhea and can produce fever or abdominal pain. Infectious colitis must be differentiated from other etiologies of colitis. It is critical to elicit a complete history from the patient, including recent travel, unusual ingestions suspect for food poisoning, similar illnesses among family members, recent hospitalizations, treatment with antibiotics, sexual history, immunosuppression, and evidence of systemic disease.

Diarrhea that develops during antibiotic administration may be related to a change in the bacterial flora of the colon. This resolves spontaneously after cessation of therapy. However, a minority of patients on antibiotics have a proliferation of the toxin-producing strains of Clostridium difficile, a gram-positive, anaerobic organism. It is now known that any antibiotic can produce this colitis. Patients present with watery diarrhea, fever, and leukocytosis. Abdominal pain and tenderness also are common. Some patients develop toxic megacolon. Symptoms can occur both during antibiotic administration and weeks to months after cessation of treatment. The diagnosis is made by rapid immunoassays that test for antigens or toxins in the stool. On endoscopic exam, the mucosa can look inflamed or develop plaque-like membranes, which is why it has been called “pseudomembranous” colitis.

Volvulus

Intestinal volvulus is a closed-loop obstruction of the bowel resulting from an axial twist of the intestine upon its mesentery of at least 180 degrees; this results in luminal obstruction and progressive strangulation of the blood supply. The early diagnosis and treatment of volvulus are important in avoiding intestinal ischemia or gangrene that can lead to a high morbidity and mortality.

The more common sigmoid volvulus usually presents with the triad of abdominal pain, distention, and obstipation. Upon questioning, one often elicits a history of previous attacks. On exam, the abdomen is distended dramatically, with high-pitched bowel sounds and tympany to percussion. The diagnosis may be confirmed with an abdominal radiograph (Fig. 25.6). Minimal tenderness may be elicited in spite of this presentation.

When patients do not show signs of intestinal strangulation, the initial treatment of choice is endoscopic decompression; this allows the volvulus to reduce so that surgical treatment can be performed electively, after a full mechanical bowel preparation, with lower morbidity and mortality. Rigid sigmoidoscopy can reduce and decompress the bowel, evaluate the rectal and colonic mucosa, and allow for the passage of a rectal tube to keep the bowel decompressed. Endoscopic decompression is successful about 85% of the time.

460 S.F. Lowry and T.E. Eisenstat

Figure 25.6. Classic sigmoid volvulus. Note that pelvis of kidney bean–shaped volvulus points to origin of volvulus. (Reprinted from Schecter WP. Peritoneum and Acute Abdomen. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001, with permission.)

Patients with gangrene may present with a more fulminating picture of systemic illness and an acute abdomen. The goals of treatment are to untwist and decompress the bowel before strangulation and to prevent recurrences. Those patients admitted with signs of sepsis indicative of gangrenous bowel must be resuscitated aggressively and taken emergently to the operating room.

Cecal volvulus is the second most common type of volvulus, although it is the cause of only 1% of all intestinal obstructions. Most patients present with symptoms of a small-bowel obstruction: nausea, vomiting, cramping, abdominal pain, and distention. Two types of volvulus can occur: an ileocolic twisting, generally in a clockwise direction; or a cecal bascule, which is an anterior and superior folding of the cecum over the ascending colon. The latter is much less common, occurring 10% of the time.

These patients cannot be reduced endoscopically and require operation for definitive treatment. If the bowel is gangrenous, right hemicolectomy with ileostomy is the standard treatment. The mortality of this procedure ranges from 22% to 40%. However, if no perforation is present and the patient is hemodynamically stable, then an ileocolectomy and primary anastomosis may be performed safely.

25. Colon and Rectum 461

Malignant Diseases

Incidence

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of death by cancer in the United States (estimated at 15% of all malignancies). Approximately 30% are located in the rectum, 28% in the sigmoid, 9% in the descending colon, 11% in the transverse colon, 9% in the ascending colon, and 13% in the cecum.

Screening and Surveillance

Cancer screening refers to the testing of a population of apparently asymptomatic individuals to determine the risk of developing colorectal cancer. Various screening and surveillance modalities are available to detect colorectal cancers and adenomatous polyps (Table 25.2). Surveillance refers to the ongoing monitoring of individuals who have an increased risk for the development of a disease. For colorectal cancer, surveillance is reserved for patients with inflammatory bowel disease, family cancer syndromes, APC disorders, and a previous history of colorectal cancer or colorectal adenomas.

Signs and Symptoms

The presentation of large-bowel malignancy generally falls into three categories: insidious onset of chronic symptoms, acute onset of intestinal obstruction, and acute perforation. The most common presentation is that of an insidious onset of chronic symptoms (77–92%), followed by obstruction (6–16%), and perforation with local or diffuse peritonitis (2–7%).

As in Case 2, bleeding is the most common symptom of colorectal malignancy. Unfortunately, patient and physician alike often attribute the bleeding to hemorrhoids. Change in bowel habits is the second most common complaint, with patients noting either diarrhea or constipation. Perforation is the third general class of presentation of colorectal malignancy. It may result in localized peritonitis or gen-

Table 25.2. Patients who should be screened or in surveillance programs.

Screen |

|

|

|

Surveillance |

Average risk and |

Average risk |

Average risk and |

|

Personal |

symptoms |

and age >50 |

request screen |

Increased risk |

history |

Change in bowel |

|

|

Family history of |

IBD, previous |

habits, per anal |

|

|

CRC, adenomas in 1st- |

adenomas, |

bleeding, unclear |

|

|

degree relatives <60 |

previous |

abdominal pain, |

|

|

years old, genetic |

CRC, genetic |

unclear anemia |

|

|

family syndrome |

syndromes |

|

|

|

(HNPCC, FAP) |

|

CRC, colorectal carcinoma; FAP, familial adenomatous polyposis; HNPCC, hereditary nonpolyposis coli syndrome; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Source: Reprinted from Welton ML, Varma MG, Amerhauser A. Colon, rectum, and anus. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001, with permission.

462 S.F. Lowry and T.E. Eisenstat

eralized peritonitis, or, if walled off, it may present with obstruction or fistula to an adjacent structure, such as the bladder.

Staging

Staging systems are important for predicting outcomes, selecting patients for various therapies, and comparing therapies for like patients across institutions. For a tumor to be considered as an invasive cancer and staged, it must penetrate through the muscularis mucosa. Several classification systems are utilized, including the Dukes, which is based on the extent of direct extension, along with the presence or absence of regional lymphatic metastases for the staging of rectal cancer. Dukes’ A lesions are those in which the depth of penetration of the primary tumor is confined to the bowel wall. Dukes’ B lesions have primary tumor penetration through the full thickness of the bowel to include serosa or fat. Dukes’ C lesions have local (C1) or regional (C2) nodal involvement. Although not initially described, it became accepted by common practice to add a fourth category for distant spread (D) outside the resected specimen.

The TNM (tumor/node/metastasis) classification was proposed by the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer to incorporate findings at laparotomy. The stages of the TNM system roughly correlate to the stages of Dukes’ C; stage 4 is the equivalent of Dukes’ D (Tables 25.3 and 25.4).

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has settled on two classifications: low grade (well and moderately differentiated) and high grade (poorly and undifferentiated). DNA ploidy assessment is the

Table 25.3. TNM staging system.

Stage |

Depth |

Nodal status |

Distant metastasis |

Stage 1 |

T1, T2 |

N0 |

M0 |

Stage 2 |

T3, T4 |

N0 |

M0 |

Stage 3 |

Any T |

Any N (except N0) |

M0 |

Stage 4 |

Any T |

Any N |

M1 |

|

|

|

|

TX |

Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

|

|

T0 |

No evidence of primary tumor |

|

|

Tis |

Carcinoma in situ |

|

|

T1 |

Tumor invades into submucosa |

|

|

T2 |

Tumor invades into muscularis propria |

|

|

T3 |

Tumor invades through muscularis propria |

|

|

T4a |

Tumor perforates visceral peritoneum |

|

|

T4b |

Tumor directly invades other structures |

|

|

NX |

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

|

|

N0 |

No regional lymph nodes |

|

|

N1 |

1–3 regional lymph nodes |

|

|

N2 |

More than 4 regional lymph nodes |

|

|

N3 |

Regional lymph nodes along a named vascular trunk |

|

|

MX |

Presence of distant metastasis cannot be assessed |

|

|

M0 |

No distant metastases |

|

|

M1 |

Distant metastases |

|

|

Source: Reprinted from Welton ML, Varma MG, Amerhauser A. Colon, rectum, and anus. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001, with permission.

25. Colon and Rectum 463

Table 25.4. Comparison of TNM system to Dukes’ classification.

|

Tumor |

Nodes |

Distant disease |

A |

Tis, T1, T2 |

N0 |

M0 |

|

T3 |

|

|

B |

T4 |

N0 |

M0 |

C1 |

T1, T2, T3 |

Any N (except N0) |

M0 |

C2 |

T4 |

Any N (except N0) |

M0 |

D |

ANY T |

ANY N |

M1 |

Source: Reprinted from Welton ML, Varma MG, Amerhauser A. Colon, rectum, and anus. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001, with permission.

measurement of the quantum amount of DNA in cells. Diploidy is correlated with good prognoses; aneuploidy is correlated with poor prognoses. Bowel perforation and elevated preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) are associated with poorer prognosis.

Preoperative Staging for Colorectal Cancer

The general physical examination remains a cornerstone in assessing a patient preoperatively to determine the extent of the local disease, disclosing distant metastases, and appraising the general operative risk. Special attention should be paid to weight loss, pallor as a sign of anemia, and signs of portal hypertension. In addition, a complete workup should include the investigations listed in Table 25.5.

Cancer of the Colon

Natural History

Surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment for colorectal cancer, but it has inherent limitations imposed by the biology and stage of the tumor as well as its location. Ultimately, 50% of patients who undergo curative resection develop local, regional, or widespread recurrence. Operative management is discussed briefly below, and additional therapies, based on pathologic findings, are outlined in Algorithm 25.5.

Table 25.5. Preoperative evaluation for colorectal malignancy.

Routine blood work

Colonoscopy

Radiographs

Ultrasound

CBC, LFT, CEA

Tissue diagnosis, synchronous disease

CXR, seleced CT abdomen/pelvis

Transrectal ultrasound

CBC, complete blood count; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CT, computed tomography; CXR, chest x-ray; LET, liver function test.

Source: Reprinted from Welton ML, Varma MG, Amerhauser A. Colon, rectum, and anus. In: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, et al, eds. Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2001, with permission.

464 S.F. Lowry and T.E. Eisenstat

Preliminary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stage* |

|

|

|

|

Adjuvant |

|

|||||

|

concerns |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Favorable |

|

Observe |

Stage 0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

Pedunculated |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carcinoma in situ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

features |

|

|

|

|

None |

|||||||||||||||||||||

polyp removed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

Unfavorable |

|

|

|

Stage 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

endoscopically |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Colectomy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

features |

|

T1N0M0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

Sessile polyp |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Colectomy |

|

|

T2N0M0 |

|

|

|

None |

||||||||||||||||||

with cancer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

AC–A1, B1 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dukes A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stage 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Invasive, nonobstructing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Colectomy |

|

|

|

None, except T4 |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T3N0M0 |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(controversial) |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Diversion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Resection at a |

T4N0M0 |

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

Obstructing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

second stage |

AC–B2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

cancer |

|

|

|

|

|

Colectomy |

|

|

|

|

|

Hartmann’s |

Dukes B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

resection |

Stage 3 |

|

|

|

5-FU and leucovorin, |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anastomosis, |

Any T with +nodes |

|

|

|

or levamisole |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Special conditions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

diverson |

AC–C1, C2 |

|

|

|

If metachronous, |

|||||||||||||

|

• Familial polyposis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|