Revision Sinus Surgery

.pdf

Indications for Revision Endoscopic Sinus Surgery

nical factors that may not be revealed on endoscopy, such as residual ethmoid cells, obstructions to sinus drainage, or mucocele formation. Disease load can be determined by identifying the number of sinuses involved with disease and the extent of their involvement (mucosal thickening vs. opacification). The Lund-MacKay staging system is an effective method of standardizing reporting of radiologic severity of disease [3,9]. Care must be exercised in the face of exuberant local disease out of proportion to the rest of the sinus cavities to ensure against a missed diagnosis of neoplasm such as inverted papilloma.

When frontal sinus involvement is suspected, helical CT with three-dimensional reconstruction is needed for analysis of the anatomy of the frontal recess. Frontal sinus opacification is often noted on CT. However, this radiologic finding also needs to be assessed in terms of clinical context by assessing the patient’s symptoms. For example, it is not unusual in extensive sinonasal polyposis for patients to demonstrate a significant amount of frontal sinus involvement. Thus, in patients with nasal polyposis, frontal sinus opacification in the absence of frontal symptoms or bony remodeling is not in and of itself an indication for revision.

The Role of Image-Guided Surgery

When ordering imaging studies, consideration should be given to the possibility of image-guided surgery as part of the initial evaluation of the potential surgical patient. The rationale for this is that normal anatomy is invariably altered in previously operated patients, and the usual anatomic landmarks – including the middle turbinate, uncinate process, and basal lamella – may have been removed. Formal indications for computer-aided surgery endorsed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery are [1]:

1.Revision sinus surgery.

2.Distorted sinus anatomy of development, postoperative, or traumatic origin.

3.Extensive sinonasal polyposis.

4.Pathology involving the frontal, posterior ethmoid, and sphenoid sinuses.

5.Disease abutting the skull base, orbit, optic nerve, or carotid artery.

6.CSF rhinorrhea or conditions where there is a skullbase defect.

7.Benign and malignant sinonasal neoplasms.

17

pain: neuralgia, migraine equivalent (midfacial headache), or dental problems may be responsible. The axial CT should be used to carefully assess the possibility of a small periapical dental abscess producing pain. In individuals with a history of migraine or multiple surgeries, a trial of amitriptyline may be warranted.

Surgery

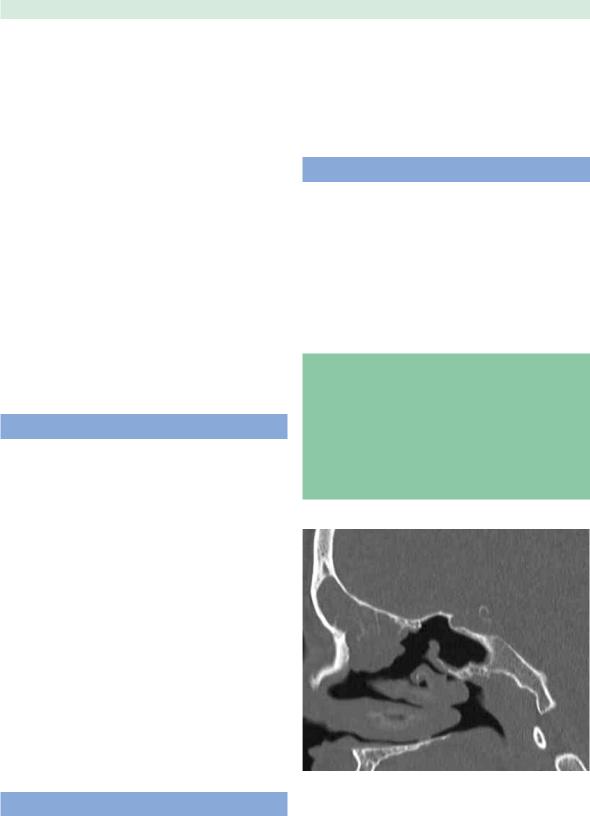

The role of revision surgery is principally to improve medical management, and surgery should be planned and executed to optimize this. This is achieved by either reducing disease load, by removing recurrent nasal polyps or hypertrophic sinonasal mucosa (Fig. 2.5), or improving access for continuing medical care in the form of topical solutions. Wide antrostomies are created for problem sinuses in order to provide better access for irrigating solutions. Continued postoperative medical therapy is essential and can be considered an integral part of surgical care.

Tips and Pearls

1.Ensure an adequate trial of maximal medical therapy before planning surgery.

2.Surgery is indicated only after failure of appropriate medical management.

3.Be wary of pain as a sole presenting symptom in the absence of other physical findings.

4.Know when and how to use navigation.

5.Know your limitations as a surgeon – be realistic.

Other Causes

In patients with post-ESS symptoms where no origin for their symptoms can be identified, other causes of sinonasal symptoms should be considered. In the case of facial

Fig. 2.5 Recurrence of sinonasal polyposis. Sagittal CT showing extensive soft-tissue changes and polypoid disease in the region of the frontal recess. Note is made of the persistence of the anterior ethmoid cells, which indicates that previous surgery has not addressed these areas

|

18 |

|

References |

2 |

1. AAO-HNS Policy on Intra-Operative Use of Computer- |

Aided Surgery (2005) American Academy of Otolaryngol- ogy-Head Neck Surgery. http://www.entlink.net/practice/ rules/image-guiding.cfm

Marc A. Tewfik and Martin Desrosiers

9.Kountakis SE, Bradley DT (2003) Effect of asthma on sinus computed tomography grade and symptom scores in patients undergoing revision functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol 17:215–219

10.Maniglia AJ (1991) Fatal and other major complications of endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope 101:349–354

2.Batra PS, Citardi MJ (2006) Endoscopic management of si11. Musy PY, Kountakis SE (2004) Anatomic findings in pa-

nonasal malignancy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 39:519– 637, x–xi

3.Bhattacharyya N (1999) Computed tomographic staging and the fate of the dependent sinuses in revision endoscopic sinus surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 125:994–999

4.Briggs RD, Wright ST, Cordes S, et al. (2004) Smoking in chronic rhinosinusitis: a predictor of poor long-term outcome after endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope 114:126–128

5.Chee L, Graham SM, Carothers DG, et al. (2001) Immune dysfunction in refractory sinusitis in a tertiary care setting. Laryngoscope 111:233–235

6.Chiu AG, Vaughan WC (2004) Revision endoscopic frontal sinus surgery with surgical navigation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 130:312–318

7.Chu CT, Lebowitz RA, Jacobs JB (1997) An analysis of sites of disease in revision endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol 11:287–291

8.Dessi P, Castro F, Triglia JM, et al. (1994) Major complications of sinus surgery: a review of 1192 procedures. J Laryngol Otol 108:212–215

tients undergoing revision endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Otolaryngol 25:418–422

12.Oikawa K, Furuta Y, Itoh T, et al. (2007) Clinical and pathological analysis of recurrent inverted papilloma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 116:297–303

13.Parsons DS, Stivers FE, Talbot AR (1996) The missed ostium sequence and the surgical approach to revision functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 29:169–183

14.Ramadan HH (1999) Surgical causes of failure in endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope 109:27–29

15.Schlosser RJ, Bolger WE (2004) Nasal cerebrospinal fluid leaks: critical review and surgical considerations. Laryngoscope 114:255–265

16.Stankiewicz JA (1989) Complications of endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 22:749–758

17.Wormald PJ, Ooi E, van Hasselt CA, et al. (2003) Endoscopic removal of sinonasal inverted papilloma including endoscopic medial maxillectomy. Laryngoscope 113:867–873

18.Zhang G, Rodriguez X, Hussain A, et al. (2007) Outcomes of the extended endoscopic approach for management of inverted papilloma. J Otolaryngol 36:83–87

Chapter 3

Predictors of Failure

of Primary Surgery

Iman Naseri and John M. DelGaudio

Core Messages

■Surgical success should be defined as significant symptom improvement or resolution, in addition to improvement of mucosal inflammation and sinus obstruction.

■Identification and maximal medical management of coexisting disease factors must be considered prior to ensuing surgical treatment to improve the results of endoscopic sinus surgery.

■Smoking has been found to increase the likelihood of a poor surgical outcome, and reflux disease is more common in surgically refractory patients with chronic rhinosinusitis.

■Significant nasal polyposis and advanced LundMacKay scores increase the chance of long-term failure of primary surgery.

Introduction

Endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) is the preferred treatment for patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) that has failed to respond to maximal medical treatment. ESS has been found to be effective in up to 90% of patients, with long-term symptomatic improvement in up to 98% of patients [7, 16, 17, 24, 37, 39].

Multiple factors are implicated in the increased the risk for failure of primary ESS. These include [6, 7, 16, 39]:

1.Allergies.

2.Tobacco use.

3.Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) disease.

4.Previous open sinus procedures.

5.Severe mucosal disease.

6.Stage of sinus disease.

7.Inadequate postoperative care.

8.Scarring and synechiae.

9.Inadequate surgery.

3

Contents |

|

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

. 19 |

Patient Selection Factors . . . . . . . . . . . . |

. 20 |

Comorbidities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

20 |

Disease Factors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21 |

|

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

22 |

The overall success rate of primary endoscopic sinus surgery ranges from 80 to 97% based on several criteria used to measure success [4, 9, 12, 13, 16, 24, 28, 36, 37, 43, 44]. It was shown that the extent of the disease measured preoperatively by computed tomography (CT) may dictate the surgical outcome [16]. CT scans and endoscopic examinations are used as outcome measurements in conjunction with subjective symptom evaluations. Among the staging systems that utilize CT scans, the LundMacKay staging system has been recommended by the Task Force on rhinosinusitis of the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery [27, 45]. Two tests have been used most in clinical practice for symptom evaluation, the sinonasal outcome test (SNOT-20) and the symptom score instrument [26, 35].

Prior to discussing the factors that predispose to increased risk of failure of ESS we need to define what would be considered a failure.

■If the goal of sinus surgery is to improve or resolve sinonasal symptoms, sinus obstruction, and mucosal inflammation, then failure to accomplish these goals should be considered a failure.

By using this definition of failure, we can divide the predictors of failure into several categories, including patient selection factors, comorbidities, disease factors, and anatomic and surgical factors.

20

Patient Selection Factors

A successful surgical procedure begins with appropriate indications. ESS is indicated for CRS refractory to maxi- 3 mal medical therapy, mucoceles, extrasinus extension of

CRS, and tumors.

■Sinus surgery may not be effective in resolving symptoms of postnasal drip (PND) or headache, even if the surgical procedure is technically perfect and the sinonasal mucosa is healthy in the postoperative period.

Also, the extent of surgery performed should be dictated by the degree of sinus disease observed on a preoperative CT scan. Failure to address involved sinuses at the primary procedure is likely to result in failure.

PND is a common symptom that can be found in patients with a myriad of sinonasal diseases. In patients with PND as the primary symptom, especially when there is minimal sinus disease on CT scan, the surgeon should be careful to treat other conditions that may be more likely to cause the PND prior to recommending surgery. Wise and DelGaudio found that in patients with and without CRS, those with a complaint of PND were significantly more likely to have pathologic reflux at the level of the nasopharynx and the hypopharynx [47]. Appropriate medical treatment of reflux should be performed prior to attributing this symptom to CRS, especially in the absence of purulent nasopharyngeal drainage.

■Sinus surgery may not be effective as a treatment for headache in the absence of sinus CT findings that correlate with the location of the headache

Multiple studies have found that over 90% of patients with a diagnosis of sinus headache and a normal CT scan of the sinuses meet the International Headache Society criteria for migraine headache [38]. DelGaudio has found that approximately 90% of patients presenting with a diagnosis of sinus headache and a normal or minimally diseased CT scan of the sinuses have reduction or resolution of their headaches with treatment with triptans (personal communication). Patients with sinus disease on CT scan and headache should be counseled that the sinus surgery may not resolve their headaches, especially if the headache location does not correlate to the area of sinus involvement.

Comorbidities

Reflux disease has been implicated to be associated with CRS, and has specifically been shown to be associated with a worse prognosis for ESS. Chambers et al. retro-

Iman Naseri and John M. DelGaudio

spectively reviewed 182 patients who had undergone ESS to determine the prognostic factors for poor outcome [7]. They found that a history of GER was the only historical factor that was a predictor of poor symptom outcome after ESS. DelGaudio showed that patients with persistent symptoms of CRS and sinonasal inflammation after ESS have significantly greater degrees of reflux at all levels of the aerodigestive tract, especially the nasopharynx, when compared to controls.

■This study is the first to demonstrate that direct nasopharyngeal reflux of gastric acid is found in adults with surgically refractory CRS at a significantly higher frequency than in control patients

The likely mechanism of effect on the nasal mucosa is mucosal edema and impaired mucociliary clearance. As acid travels up the digestive tract it reaches areas with less ability to protect against the acid and digestive enzymes present in the refluxate. It is likely that the nasopharyngeal and nasal mucosa have a lower threshold for injury from gastric contents. These results support the possibility that even more minor pH drops can cause harmful effects in the upper aerodigestive tract as a result of acid or pepsin exposure [11].

The role of reflux in CRS is especially evident in the pediatric population [34]. Treatment of GER in these patients leads to improvement of their sinus disease. Studies have also shown that medically refractory chronic sinusitis patients have improvement after treatment for GER [1]. Similarly, a significant reduction in the need for sinus surgery was also seen in such patients who underwent treatment for their reflux. Thus, one must recognize that reflux may play a role in worsening of symptoms of sinus disease, and the sinus surgeon should be wary of advocating surgery without proper diagnosis and treatment for this condition.

The deleterious effects of tobacco smoke on the aerodigestive tract are well documented. Despite the strong associations, there is a lack of controlled trials demonstrating the deleterious effects of tobacco smoke on sinonasal structures. Cigarette smoking has been shown to impede mucociliary transport and increase nasal resistance [3]. Although not a contraindication for ESS, patients who continue to smoke postoperatively are at a higher risk for complications and a worse outcome [6, 39]. This is most likely due to chronic mucosal irritation from the smoke, resulting in mucosal edema, poor mucosal healing, and increased postoperative scarring and synechiae formation. Little is known about the impact of smoking cessation and the reversal of these effects. Patients should be counseled on the effects of tobacco use on the success of ESS [8].

Predictors of Failure of Primary Surgery |

21 |

Many systemic diseases can affect the health of the sinonasal mucosa and negatively impact the results of ESS. Diseases such as sarcoidosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis affect the respiratory tract and cause nasal mucosal inflammation, crusting, and dryness, which have a significant negative impact on healing after surgery. These patients have extensive edema and crusting postoperatively that frequently results in scarring and synechiae formation. ESS should only be performed in these patients if absolutely necessary, and only after maximal medical therapy has failed and the underlying systemic inflammatory condition has been controlled as much as possible.

Disease Factors

The most important factors that determine whether a patient is likely to have a poorer long-term outcome from ESS are related to the underling sinonasal disease factors. Like other chronic conditions, the worse the disease at the time of surgery, the greater the likelihood of persistence or recurrence. Factors that have been shown to predict failure of primary ESS include nasal polyps, ciliary dysmotility, advanced Lund-MacKay score, hyperostosis of the sinonasal bones, and asthma.

Nasal polyps, regardless of their underlying etiology, represent an advanced stage of mucosal inflammation. In addition to causing sinonasal obstruction, the polypoid mucosa inhibits normal mucociliary clearance [46]. Since the treatment of inflammation is predominantly a medical endeavor, it is not surprising that patients with polyps have a lower long-term success rate with ESS when compared to CRS patients without polyps.

■Sinus surgery in patients with polyps is directed at reducing the obstructive symptoms and reducing the inflammatory load so that medical therapy has a greater likelihood of controlling the underlying disease

There is an established relationship between nasal polyposis and the need for revision ESS [15, 20, 23]. There is also a higher rate of revision surgery in the polyp versus CRS patients [10]. Liu et al. demonstrated that sinus surgery in patients with bilateral maxillary rhinosinusitis from polyps has a 20.5% success rate [25]. Overall, patients with nasal polyposis typically have worse postoperative outcomes both objectively and subjectively when compared to CRS alone. Higher preoperative Lund-MacKay scores seen in the presence of nasal polyposis may be attributed to the bulk and mass effect of the polyps on imaging. Subjectively, patients with polyps have higher SNOT-20 scores than those with CRS. Deal et al. postulate that higher degrees of nasal obstruction in addition

to the sequelae from decreased mucociliary transport may explain such observations [10].

As expected, patients with nasal polyposis have worse postoperative endoscopic findings and symptom scores than their CRS counterparts. Even at 1 year postoperatively, they have been found to have more severe disease, as evidenced by CT and endoscopy [45]. When bilateral nasal polyposis exists along with allergies, various immune interactions exist to cause a significant increase in their recurrence rates after surgery [40–42]. Thus, it is important to identify such patients and maximize their treatment for allergies.

■Asthma has been indicated for causing a significant increase in the need for revision surgery, and some would argue that it is the most important prognostic indicator for surgical failure [20, 22].

The frequency increases to 36–96% in aspirin-sensitive patients with asthma [2, 21]. Various reports have quoted the rate of nasal polyposis in asthmatics to be as high as 41% [22, 30]. Lawson et al. demonstrated a 50% success rate with asthmatics undergoing primary surgery, compared to 88% success among nonasthmatics [22]. Batra et al. demonstrated that improved postoperative sinonasal symptoms correlate directly with Lund-MacKay scores. In addition, aspirin-sensitive patients had higher LundMacKay scores preand postoperatively when compared with their aspirin-tolerant counterparts [2].

In patients with advanced disease, chronic use of systemic steroids has been associated with the need for revision ESS. These patients are likely to have hyper-reactive airway disease and must be properly identified because they are more likely to fail primary surgery and will require longer follow-up [31]. Strict control of asthma is strongly encouraged in the perioperative management of such patient groups.

■The correlation between asthma and CRS/nasal polyps most likely reflects the effect of an inflammatory process on the entire respiratory tract (the unified airway concept).

Recurrence rates are also higher in patients recognized to have Samter’s triad (asthma, nasal polyps, and sensitivity to aspirin). Endoscopic sinus surgery for such patients has indicated a reduction of both upperand lower-air- way symptoms. This has been demonstrated by lower Lund-MacKay scores and improved pulmonary function tests [2]. Although not adopted as a standard regimen, the use of leukotriene inhibitors may have a role in the treatment of nasal polyposis, especially in the presence of Samter’s triad.

22

Chronic rhinosinusitis is very common among patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). This population suffers from one of the highest rates of refractory CRS [32]. Because of the presence of ciliary dysmotility, these patients are at con-

3 stant risk for life-threatening pulmonary infections. The deficiency of the CF transmembrane regulator protein causes chloride channel dysfunction at the epithelial cells of the upper respiratory tract. The resultant increase of sodium chloride in these cells leads to dehydration of the extracellular fluids and accumulation of thickened secretions in the sinonasal cavities [48]. Up to 50% of pediatric CF patients have nasal polyposis, and this patient population typically requires multiple surgeries throughout life. These patients should be treated aggressively both medically and surgically as they present a significant challenge because of the significant effect that the sinus disease has on pulmonary function. Nonetheless, all patients with CF require careful follow-up and frequent endoscopic examinations.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease that may cause inflammatory rhinosinusitis refractory to the traditional treatments. In a study from the Mayo clinic involving 2319 patients with sarcoidosis, 9% had head and neck manifestations, and 1% had sinonasal involvement [29]. The clinical signs may mimic chronic rhinitis or CRS with extensive crusting. These patients should be treated with high suspicion for the diagnosis of sinonasal sarcoidosis [5]. Definitive diagnosis should be made by endoscopyguided biopsy of suspicious lesions to rule out chronic noncaseating granulomas. Extensive crusting and edema in the postoperative period can lead to synechiae and obstruction.

Osteitis has been shown to be present in the sinus bone of CRS specimens [14, 18, 33]. Kim et al. evaluated the effect of osteitis on surgical outcome in patients undergoing ESS for CRS. They found that the success rate of ESS for patients with preoperative CT scan evidence of osteitis was 51.9%, compared to a success rate of 75.9% in patients without CT evidence of osteitis [19]. The reason for this is unknown and requires further study. Longer treatment with antibiotics or anti-inflammatory agents may be necessary in the perioperative period in this group of patients.

Conclusion

Primary ESS has a very high rate of success, especially if the surgery is performed meticulously and for the appropriate indications. Predictors of failure include inappropriate patient selection, failure to medically address comorbidities, advanced sinonasal disease severity, and anatomic factors. Careful attention to each of these factors preoperatively may help to reduce failures.

Iman Naseri and John M. DelGaudio

References

1.Barbero GJ (1996) Gastroesophageal reflux and upper airway disease. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 29:27–38

2.Batra PS, Kern RC, Tripathi A, Conley DB, Ditto AM, et al. (2003) Outcome analysis of endoscopic sinus surgery in patients with nasal polyps and asthma. Laryngoscope 113:1703–1706

3.Benninger MS (1999) The impact of cigarette smoking and environmental tobacco smoke on nasal and sinus disease: a review of the literature. Am J Rhinol 13:435–438

4.Biedlingmaier JF (1993) Endoscopic sinus surgery with middle turbinate resection: results and complications. Ear Nose Throat J 72:351–355

5.Braun JJ, Gentine A, Pauli G (2004) Sinonasal sarcoidosis: review and report of fifteen cases. Laryngoscope 114:1960–1963

6.Briggs RD, Wright ST, Cordes S, Calhoun KH (2004) Smoking in chronic rhinosinusitis: a predictor of poor long-term outcome after endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope 114:126–128

7.Chambers DW, Davis WE, Cook PR, Nishioka GJ, Rudman DT (1997) Long-term outcome analysis of functional endoscopic sinus surgery: correlation of symptoms with endoscopic examination findings and potential prognostic variables. Laryngoscope 107:504–510

8.Das S, Becker AM, Perakis H, Prosser JD, Kountakis SE (2007) The effects of smoking on short-term quality of life outcomes in sinus surgery. Laryngoscope (in press)

9.Davis WE, Templer JW, LaMear WR (1991) Patency rate of endoscopic middle meatus antrostomy. Laryngoscope 101:416–420

10.Deal RT, Kountakis SE (2004) Significance of nasal polyps in chronic rhinosinusitis: symptoms and surgical outcomes. Laryngoscope 114:1932–1935

11.DelGaudio JM (2005) Direct nasopharyngeal reflux of gastric acid is a contributing factor in refractory chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope 115:946–957

12.Hoffman SR, Dersarkissian RM, Buck SH, Stinziano GD, Buck GM (1989) Sinus disease and surgical treatment: a results oriented quality assurance study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 100:573–577

13.Hoffman SR, Mahoney MC, Chmiel JF, Stinziano GD, Hoffman KN (1993) Symptom relief after endoscopic sinus surgery: an outcomes-based study. Ear Nose Throat J 72:413–414

14.Jang YJ, Koo TW, Chung SY, Park SG (2002) Bone involvement in chronic rhinosinusitis assessed by 99mTc-MDP bone SPECT. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci 27:156–161

15.Jiang RS, Hsu CY (2002) Revision functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 111:155–159

16.Kennedy DW (1992) Prognostic factors, outcomes and staging in ethmoid sinus surgery. Laryngoscope 102:1–18

Predictors of Failure of Primary Surgery

17.Kennedy DW, Wright ED, Goldberg AN (2000) Objective and subjective outcomes in surgery for chronic sinusitis. Laryngoscope 110:29–31

18.Khalid AN, Hunt J, Perloff JR, Kennedy DW (2002) The role of bone in chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope 112:1951–1957

19.Kim HY, Dhong HJ, Lee HJ, Chung YJ, Yim YJ, et al. (2006) Hyperostosis may affect prognosis after primary endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 135:94–99

20.King JM, Caldarelli DD, Pigato JB (1994) A review of revision functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope 104:404–408

21.Larsen K (1996) The clinical relationship of nasal polyps to asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc 17:243–249

22.Lawson W (1991) The intranasal ethmoidectomy: an experience with 1,077 procedures. Laryngoscope 101:367–371

23.Lazar RH, Younis RT, Long TE, Gross CW (1992) Revision functional endonasal sinus surgery. Ear Nose Throat J 71:131–133

24.Levine HL (1990) Functional endoscopic sinus surgery: evaluation, surgery, and follow-up of 250 patients. Laryngoscope 100:79–84

25.Liu CM, Yeh TH, Hsu MM (1994) Clinical evaluation of maxillary diffuse polypoid sinusitis after functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol 8:7–11

26.Lund VJ, Holmstrom M, Scadding GK (1991) Functional endoscopic sinus surgery in the management of chronic rhinosinusitis. An objective assessment. J Laryngol Otol 105:832–835

27.Lund VJ, Kennedy DW (1997) Staging for rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 117:S35–50

28.Matthews BL, Smith LE, Jones R, Miller C, Brookschmidt JK (1991) Endoscopic sinus surgery: outcome in 155 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 104:244–246

29.McCaffrey TV, McDonald TJ (1983) Sarcoidosis of the nose and paranasal sinuses. Laryngoscope 93:1281–1284

30.McFadden EA, Woodson BT, Fink JN, Toohill RJ (1997) Surgical treatment of aspirin triad sinusitis. Am J Rhinol 11:263–270

31.Moses RL, Cornetta A, Atkins JP Jr, Roth M, Rosen MR, et al. (1998) Revision endoscopic sinus surgery: the Thomas Jefferson University experience. Ear Nose Throat J 77:190–195

32.Moss RB, King VV (1995) Management of sinusitis in cystic fibrosis by endoscopic surgery and serial antimicrobial lavage. Reduction in recurrence requiring surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 121:566–572

33.Perloff JR, Gannon FH, Bolger WE, Montone KT, Orlandi R, et al. (2000) Bone involvement in sinusitis: an apparent pathway for the spread of disease. Laryngoscope 110:2095–2099

23

34.Phipps CD, Wood WE, Gibson WS, Cochran WJ (2000) Gastroesophageal reflux contributing to chronic sinus disease in children: a prospective analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 126:831–836

35.Piccirillo JF, Merritt MG Jr, Richards ML (2002) Psychometric and clinimetric validity of the 20-Item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-20). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 126:41–47

36.Schaefer SD, Manning S, Close LG (1989) Endoscopic paranasal sinus surgery: indications and considerations. Laryngoscope 99:1–5

37.Schaitkin B, May M, Shapiro A, Fucci M, Mester SJ (1993) Endoscopic sinus surgery: 4-year follow-up on the first 100 patients. Laryngoscope 103:1117–1120

38.Schreiber CP, Hutchinson S, Webster CJ, Ames M, Richardson MS, et al. (2004) Prevalence of migraine in patients with a history of self-reported or physician-diagnosed “sinus” headache. Arch Intern Med 164:1769–1772

39.Senior BA, Kennedy DW, Tanabodee J, Kroger H, Hassab M, et al. (1998) Long-term results of functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope 108:151–157

40.Settipane GA (1996) Epidemiology of nasal polyps. Allergy Asthma Proc 17:231–236

41.Settipane GA (1996) Nasal polyps and immunoglobulin E (IgE). Allergy Asthma Proc 17:269–273

42.Settipane GA, Klein DE, Settipane RJ (1991) Nasal polyps. State of the art. Rhinol Suppl 11:33–36

43.Smith LF, Brindley PC (1993) Indications, evaluation, complications, and results of functional endoscopic sinus surgery in 200 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 108:688–696

44.Stammberger H (1986) Endoscopic endonasal surgery – concepts in treatment of recurring rhinosinusitis. Part II. Surgical technique. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 94:147– 156

45.Toros SZ, Bolukbasi S, Naiboglu B, Er B, Akkaynak C, at al. (2007) Comparative outcomes of endoscopic sinus surgery in patients with chronic sinusitis and nasal polyps. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 264:1003–1008

46.Waguespack R (1995) Mucociliary clearance patterns following endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope 105:1–40

47.Wise SK, Wise JC, DelGaudio JM (2006) Association of nasopharyngeal and laryngopharyngeal reflux with postnasal drip symptomatology in patients with and without rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol 20:283–289

48.Yung MW, Gould J, Upton GJ (2002) Nasal polyposis in children with cystic fibrosis: a long-term follow-up study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 111:1081–1086

Chapter 4 |

4 |

Pathophysiology of Inflammation |

|

in the Surgically Failed Sinus Cavity |

Wytske J. Fokkens, Bas Rinia and Christos Georgalas

Core Messages

■Chronic rhinosinusitis with or without polyps is an inflammatory disease. Treatment should always consist of a sandwich of optimal medical treatment, if necessary followed by surgery and than always followed by a (sometimes extensive) period of medical treatment.

■Both extrinsic and intrinsic patient factors may be associated with an unfavourable outcome after endoscopic sinus surgery.

■A careful assessment of these factors may serve as a helpful prognostic indicator of the outcome of endoscopic sinus surgery.

■Optimising the management of underlying systemic disease is vital in order to achieve a satisfactory outcome, especially in revision surgery.

Introduction

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) with or without polyps is an inflammatory disease of the nose and the paranasal sinuses characterised by symptoms of nasal blockage/obstruction/congestion, nasal discharge (anterior/posterior nasal drip), facial pain/pressure, and deterioration or loss of the sense of smell [1]. Treatment should always consist of a sandwich of optimal medical treatment, if necessary followed by surgery and then always followed by a (sometimes extensive) period of medical treatment.

The primary goal of medical treatment is the reduction or resolution of the underlying inflammation. The primary goal of surgical treatment is to remove irreversibly diseased mucosa, to aerate the sinuses and to render them more accessible to medical treatment. Although most ear-nose-and-throat surgeons currently use sandwich therapy, approximately 10% of patients respond poorly to sinus surgery with concomitant medical therapy and

Contents |

|

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

. 25 |

Intrinsic factors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

. 26 |

Allergy and Atopy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

26 |

Asthma . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

. 26 |

Acetylsalicylic Acid intolerance . . . . . . . . |

. 26 |

“Osteitis” – the Role of Bone . . . . . . . . . |

. 27 |

Cystic Fibrosis and Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia . |

. 27 |

Immune Disorders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

27 |

Non-acquired Immunodeficiency Disorders . . . . . . . |

. 27 |

Specific Mucosal Diseases . . . . . . . . . . . |

27 |

Wegener’s Granulomatosis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

. 28 |

Sarcoidosis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

. 29 |

Churg-Strauss Syndrome . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

. 29 |

External Factors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

30 |

Microbiology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

30 |

Bacteria and Biofilms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

. 30 |

Fungus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

. 30 |

Environmental Factors . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

31 |

Acquired Immunodeficiency Disorders . . . . . . |

31 |

Human Immunodeficiency Virus . . . . . . . |

. 31 |

Bone Marrow Transplantation . . . . . . . . . |

31 |

Helicobacter pylori and Laryngopharyngeal

Reflux . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Immunopathophysiology . . . . . . . . . . . . |

32 |

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

32 |

eventually undergo a secondary surgical procedure [2]. In this chapter we will assess the role of inflammation in patients who fail sinus surgery, including the role of intrinsic patient factors and external factors that adversely influence surgical outcome.

26

Intrinsic factors

CRS most likely consists of different phenotypes. The different phenotypes of CRS are often lumped together as a single disease entity, because at this moment it seems impossible to clearly differentiate between them [1]. CRS

4 with nasal polyps (NP) is one of the subgroups that has the most distinctive characteristics; some studies have attempted to use inflammatory markers in order to differentiate CRS with NP from the other subgroups [3–5]. Although some of these studies point to more pronounced eosinophilia and interleukin-5 expression in patients with NPs than in patients with CRS, these studies also suggest the existence of a continuum in which differences might be evident towards the ends of the spectrum, but no clear cut-off point exists between patients with NP and other forms of CRS. In this chapter we will refer to CRS as a single entity except when clear differences between different phenotypes are described in the literature.

There are several intrinsic factors that can give rise to, or affect the clinical course of CRS. They need to be recognised and considered because they can adversely influence sinus surgery outcome. Some of these factors may also require specific therapeutic interventions, in addition to sinus surgery.

Allergy and Atopy

■Although there is still no clear evidence of a causal link between allergy and CRS, the chances of symptomatic improvement after endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) are optimised if the underlying allergy is addressed.

It is tempting to speculate that allergic inflammation in the nose predisposes the atopic individual to the development of CRS. Both conditions share the same trend of increasing prevalence [6] and frequently coexist in the same individual. It has been postulated that swelling of the nasal mucosa in allergic rhinitis at the site of the sinus ostia may compromise ventilation and even obstruct them completely, leading to mucus retention and infection. Furthermore, there is a growing consensus that the mucosa of the nasal airway is in a continuum with the paranasal sinuses, as reflected by the use of the term “rhinosinusitis” rather than “sinusitis”.

However, critical analysis of the papers citing atopy as a risk factor for chronic rhinosinusitis reveals that whilst there appears to be a higher prevalence of allergy in patients presenting with symptoms consistent with sinusitis than would be expected in the general population, this may be the result of selection bias, as the doctors involved often had an interest in allergy [7, 8]. Among CRS patients undergoing sinus surgery, the prevalence of sensitisation ranges from 30 to 62% [9–11], of which the major-

Wytske J. Fokkens, Bas Rinia and Christos Georgalas

ity (60%) are sensitive to multiple allergens [11]. Just like in asthma, there are some indications that in patients with more severe forms of CRS, allergy is less important [11]. Notwithstanding the lack of hard epidemiologic evidence of a clear causal relationship between allergy and CRS, it is obvious that failure to address allergy as a contributing factor to CRS diminishes the chances of success of surgical intervention [12]. Half of the patients who have had sinus surgery before, believed that the surgery alone was not sufficient to completely resolve the recurrent episodes of infection [12]. However, the rate of revision surgery was not significantly different between atopic and nonatopic patients [9].

Asthma

Asthma is frequently associated with CRS and NP. In patients with concomitant asthma, a trend to suffer from more severe forms of sinus disease is observed [13]. In addition, CRS is self-reported in a very high percentage (70%) of patients suffering from asthma [14]. Asthmatic patients with concomitant CRS had more asthma exacerbations, worse asthma scores, worse cough and worse sleep quality than those without CRS.

At the cellular level the difference between asthmatic and non-asthmatic patients suffering from CRS/NP becomes evident: Patients with NP who have concomitant asthma tend to have a more prominent eosinophilic infiltration . This suggests a more aggressive inflammatory response, especially in the subgroup with aspirin-intoler- ant asthma [15–22].

These data clearly support a strong link between the lower and the upper airways. Medical and/or surgical treatment of the upper airways of asthmatics with CRS/NP, positively influences the course of bronchial asthma. Several studies report asthma symptom improvement, less asthma attacks, less steroid use (topical and systemic) and improvement in peak expiratory flow after surgery and medical treatment of the upper airways [23–25]. There is no clear evidence that CRS/NP patients with asthma benefit less from sinus surgery than patients without asthma [13, 26, 27]. Nevertheless, post-operative endoscopic findings were worse in patients with concomitant asthma [28–30], and patients with asthma did require significantly more revision sinus procedures overall [31].

Acetylsalicylic Acid intolerance

■Patients with asthma and acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) intolerance tend to have worse outcomes following functional ESS (FESS) and require revision surgery more often.

Pathophysiology of Inflammation in the Surgically Failed Sinus Cavity |

27 |

Already in 1922, Widal described a triad of symptoms, which later came to be known as the Samter’s triad: intolerance to ASA compounds (e.g. aspirin), bronchial asthma and (often severe) CRS with NP. The mechanism of the hypersensitivity reaction to aspirin is not immunological, but may be related to the inhibition of cyclo-oxy- genase (COX-1 and COX-2), an enzyme responsible for prostaglandin synthesis, by aspirin.

Symptoms of this ASA triad usually commence around the 20th year of life. Initially, patients present with nasal blocking, rhinorrhea and hyposmia followed in a couple of years by the formation of NPs and (often steroid dependent) asthma. Ingestion of aspirin (or another nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, NSAID) results in an exacerbation of rhinitis and asthma, but independent of the exposure to NSAIDs, the disease will continue lifelong. Patients suffering from CRS and/or NP with ASA intolerance tend to suffer from more extensive sinus disease. They benefit from sinus surgery, but to a lesser extent than patients without ASA intolerance [32]. However, they are more prone to disease recurrence and more frequently have to undergo revision surgery than ASAtolerant CRS/NP patients [32–34].

“Osteitis” – the Role of Bone

Areas of increased bone density and irregular bony thickening are frequently seen on CT in areas of chronic inflammation in patients with CRS and may be a marker of the underlying chronic inflammatory process [35–37]. Although to date bacterial organisms have not been identified in the bone of either humans or animal models of CRS, it has been suggested that this irregular bony thickening is a sign of bony involvement, which might in turn maintain mucosal inflammation [35–37].

Cystic Fibrosis and Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

Both cystic fibrosis (CF) and primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) manifest, among other things, with recurrent upper and lower respiratory tract infections. Patients with CF almost without exception suffer from CRS, and develop NP in approximately 50% of cases. CRS is also almost always present in patients with PCD, but the prevalence of NP in this group of patients is only about 5%. Both CF and PCD are autosomal recessive genetic diseases and should be considered in children with CRS with or without NP.

When suspected, CF can be diagnosed by means of a sweat test or DNA analysis. Ciliary activity in PCD can be investigated in a mucosa biopsy from the upper or lower airways, if necessary after culturing. A nasal brush is also a possibility as a way of collecting nasal epithelial cells.

Long-term antibiotics and local/systemic steroids are the cornerstones of treatment. Multiple surgical procedures are often needed in order to achieve symptomatic relief of the upper, as well as the lower, airways. Since mucociliary clearance is compromised in both diseases, simple FESS is often not sufficient. In addition to nasal lavages, radical sinus surgery is often unavoidable [38, 39]. Perioperative morbidity is assumed to be higher in CF patients, due to underlying medical issues, such as acquired coagulopathies and advanced pulmonary disease.

Immune Disorders

Several acquired and non-acquired immunodeficiencies can cause CRS (with or without NP). They may gravely affect the patient’s clinical course and influence the responsiveness of CRS to standard medical and surgical treatment. They should always be considered in cases of recalcitrant sinus disease.

■In cases of recalcitrant disease that is resistant to both medical and surgical treatment, the patient must be assessed for the presence of underlying congenital immunodeficiencies. However, with the exception of humoral deficiency, which may necessitate treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin, the significance of subtle immunodeficiencies is uncertain.

Non-acquired Immunodeficiency Disorders

A high percentage of patients with severe CRS, refractory to medical treatment, seem to suffer from impaired T-cell function, impaired granulocyte function [40], some form of immunoglobulin deficiency and common variable immunodeficiency [41–43]. The prognostic value of these findings, nevertheless, is limited [44–46].

Non-acquired immunodeficiencies may affect humoral, cellular and frequently both immune response pathways. These patients are at an increased risk of developing CRS [47–49]. Some examples include common variable immunodeficiency, ataxia telangiectasia and X-linked agammaglobulinaemia. Currently, there is not enough data to evaluate the role of sinus surgery in this group of patients. In patients with an identified humoral deficiency, there may be a role for concomitant intravenous immunoglobulin therapy [50].

Specific Mucosal Diseases

A few systemic inflammatory conditions are associated with CRS. Three of the most frequently encountered include Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG), sarcoidosis and