Revision Sinus Surgery

.pdf

Revision Endoscopic Surgery of the Sphenoid Sinus |

115 |

5.Musy PY, Kountakis SE (2004) Anatomic findings in pa- 8. Say P, Leopold D, Cochran G, et al. (2004) Resection of

tients undergoing revision endoscopic sinus surgery Am J Otolaryngol 25:418–422

6.Orlandi RR, Lanza DC, Bolger WE, et al. (1999) The forgotten turbinate: the role of the superior turbinate in endoscopic sinus surgery Am J Rhinol 13:251–259

7.Rosen FS, Sinha UK, Rice DH (1999) Endoscopic surgical management of sphenoid sinus disease Laryngoscope 109:1601–1606

the inferior superior turbinate: does it affect olfactory ability or contain olfactory neuronal tissue? Am J Rhinol 18:157–160

9.Wormald PJ, Athanasiadis T, Rees G, et al. (2005) An evaluation of effect of pterygopalatine fossa injection with local anesthetic and adrenalin in the control of nasal bleeding during endoscopic sinus surgery Am J Rhinol 19:288–292

Chapter 14 |

14 |

Endoscopic and Microscopic |

|

Revision Frontal Sinus Surgery |

Ulrike Bockmühl and Wolfgang Draf

Core Messages

■There must be a reasonable correlation between a patient’s complaints and radiologic findings.

■High-resolution computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are the most valid imaging modalities.

■Revision surgery is most often necessary due to incomplete removal of obstructing agger nasi cells, superior attachment of the ethmoid bulla or uncinate process (incomplete anterior ethmoidectomy), lateralization of middle-turbinate remnants, neoosteogenesis of the frontal recess, and polypoid mucosa obscuring the recess.

■Endonasal revision frontal sinus surgery requires detailed anatomical knowledge.

■In the majority of patients revision can be managed successfully via the endonasal route by performing Draf’s type I–III drainages.

■In aspirin triad, patients with severe polyposis, Draf’s type III drainage is indicated as the first revision procedure.

■Contraindications for endonasal frontal sinus revision surgery are anterior–posterior dimension less than 0.5 cm, inadequate surgical training, and lack of proper instrumentation.

■The external osteoplastic, mostly obliterative frontal sinus operation must be part of the armamentarium of the experienced sinus surgeon for the resolution of exceptionally difficult frontal sinus problems.

Contents |

|

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

117 |

Preoperative Workup . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 118 |

|

Surgical Technique . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

. 120 |

Type I Drainage According to Draf . . . . . . |

. 120 |

Type II Drainage According to Draf . . . . . . |

121 |

Type III Drainage According to Draf . . . . . |

. 121 |

Postoperative Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

. 123 |

Outcomes and Complications . . . . . . . . . |

. 124 |

Future Directions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

124 |

Introduction

Chronic frontal sinusitis is a disease that continues to pose a significant challenge to surgeons despite considerable advances in instrumentation and surgical techniques [4, 5, 11, 31, 33]. Primary endoscopic or microscopic sinus surgery can often result in scarring of the frontal recess, especially when there is an incomplete removal of obstructing agger nasi cells, superior attachment of the ethmoid bulla, or uncinate process [3, 5]. Failure to recognize frontal recess cells and supraorbital ethmoid cells can mislead the surgeon into believing the frontal recess has been opened. Other common causes of failure of primary surgery, including lateralization of middle-turbi- nate remnants, neo-osteogenesis of the frontal recess, and polypoid mucosa obscuring the recess, all contribute to the difficulty and danger of revision surgery [4]. Historically, surgeons treating recurrent or persistent frontal sinus disease advocated either reestablishing drainage from an intranasal approach, reestablishing drainage from an external approach, or obliteration of the sinus. Since the introduction of endoscopic technology to manage paranasal sinus diseases, interest in reestablishing drainage

118

from an intranasal approach has flourished and several endoscopic techniques, many bearing a resemblance to procedures developed by Draf [6], have been described. These include:

1.Anterior ethmoidectomy without alteration of the frontal ostium itself (i.e., drainage type I according to Draf) [6].

2.Endoscopic frontal sinusotomy according to Stammberger and Posawetz, characterized as “uncapping the egg” [32].

3.Enlargement of the frontal ostium medially until the middle turbinate (i.e., drainage type IIa according to Draf) [6].

4.Removal of the entire frontal floor on one side until the nasal septum in front of the olfactory fossa (i.e., drainage type IIb according to Draf) [6].

5.Median drainage of frontal sinuses removing both frontal sinus floors, upper nasal septum, and septum (septa, if several) sinuum frontalium (i.e., drainage type III according to Draf or endoscopic modified Lothrop procedure) [6, 13].

In general, the first two procedures are indicated in primary surgery, techniques 3 and 4 mainly in revision cases, and Draf’s type III drainage and the modified Lothrop procedure are most often performed as rescue surgery.

14 Using maximal medical therapy, a stepwise progression from less to more invasive procedures, and an aggressive postoperative regimen of debridement, excellent results can be achieved treating this difficult clinical problem.

Indications for revision surgery:

■Persistent chronic frontal rhinossinusitis as failure of appropriate medical therapy and/or previous surgery due to polypoid mucosa obscuring the recess.

■Persistent chronic frontal sinusitis due to anatomical particularities after previous surgery (e.g., persistent agger nasi cells, superior attached ethmoid bulla or uncinate process, lateralization of the middle turbinate, and neo-osteogenesis of the frontal recess).

■Patients with aspirin triad (i.e., polyposis, aspirin intolerance, and bronchial asthma).

■Frontal sinus mucoceles.

■Primary or recurrent tumors (i.e., inverted papilloma, osteoma, ossifying fibroma, and malignancies).

Contraindications:

■Narrow anterior–posterior (AP) dimension of the frontal sinus floor, hypoplastic frontal sinus.

■Failure of adequate endonasal type III drainage.

■Patients with aspirin triad and condition after several endonasal revision procedures.

■Inexperience of the surgeon.

■Unavailability of proper instrumentation.

Ulrike Bockmühl and Wolfgang Draf

Preoperative Workup

The decision for revision surgery is not easy to make for either the patient or the surgeon. If the patient complains about persistent or recurrent symptoms like frontal headache, reduced smelling or nasal obstruction, endoscopy of the nose is indicated first followed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) verification and, in case of likelihood for revision surgery, computed tomography (CT) scans should be performed. CT images should be scanned in the axial direction with a maximum of 0.65-mm sections, and from there, coronal as well as sagittal views should be reconstructed. The most common sign of persistent or recurrent disease is mucosal thickening within the frontal recess and/or sinus.

■Anatomic evaluation of the frontal sinus region with CT scans is key to the feasibility and safety of endoscopic or microscopic revision frontal sinus surgery.

CT scans should reveal the number and location of frontal recess air cells, as well as barriers that have to be removed to reach the internal frontal sinus ostium [10, 39].

The coronal CT views are excellent to determine the following structures:

■Remaining agger nasi cells or neo-osteogenesis of the frontal recess (Fig. 14.1).

■Superior uncinate process.

■Depth of the olfactory fossa.

■Anterior ethmoid artery.

■Bulla frontalis (cell above the agger nasi with expansion into the frontal sinus; Fig. 14.1b).

■Supraorbital ethmoid cells

Sagittal and axial CT views are important to determine the following structures:

■AP dimension of the frontal recess (Figs. 14.2 and 14.3).

■Frontal recess.

■Supraorbital ethmoid cells.

■Bulla frontalis (cell above the agger nasi with expansion into the frontal sinus).

■Interseptal frontal sinus cell.

The important anatomic AP dimension is the distance from the nasal bones at the root of the nose to the anterior skull base [12, 14, 19, 36]. This dimension includes the AP thickness of the nasal beak and the distance from the beak to the anterior skull base. Recently, it was determined that an accessible dimension of at least 5 mm is required to allow safe removal of the nasal beak and frontal sinus floor [10]. An accessible dimension less than 5 mm would preclude the patient’s candidacy for endo-

Endoscopic and Microscopic Revision Frontal Sinus Surgery |

119 |

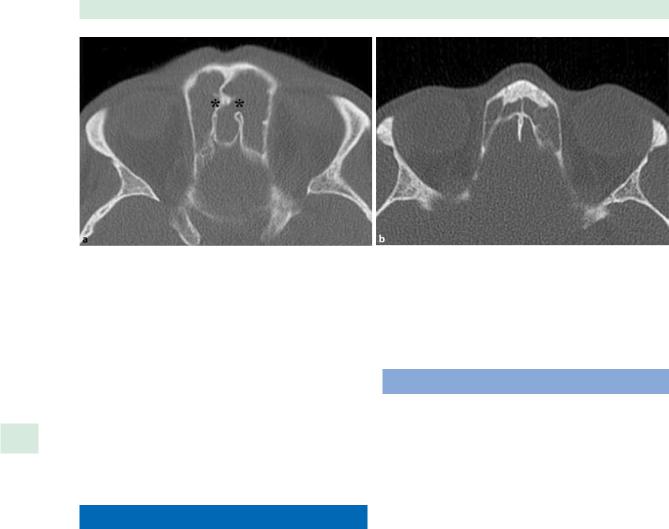

Fig. 14.1 a Coronal computed tomography (CT) view showing a recurrent chronic pansinusitis including the frontals sinuses. Above the agger nasi cells left after previous operation there are

Fig. 14.2 Sagittal CT views showing persistent chronic sinusitis after incomplete ethmoidectomy, and demonstrating different

nasal frontal sinus surgery. Furthermore, it is of utmost importance to analyze the images for dangerous anatomical findings like skull-base and lamina papyracea defects or a very deep cribriform plate. Recognizing the so-called dangerous frontal bone decreases the danger of creating a dural defect when removing an incomplete frontal sinus septum (Fig. 14.3a).

Whenever possible the updated images should be compared with the previous ones. However, there must be a reasonable correlation between patients’ complaints and radiologic findings (i.e., it should not be forgotten

cells with expansion into the frontal sinus (bullae frontales). b Coronal CT scan showing neo-osteogenesis of the right frontal recess

anterior to posterior (AP) dimensions of the frontal recess (black bar). a Wide AP dimension. b Narrow AP dimension

that the surgeon operates patients and not CTs or MRIs). In case of headaches, neurological consultation is sometimes important, particularly if the patient reports about migraine in the family.

■Prior to surgery, the patient’s underlying condition causing frontal sinus disease should be optimized medically.

Therefore, a selective combination of nasal irrigations, antibiotics, leukotriene antagonists, topical, and/or oral

120 |

Ulrike Bockmühl and Wolfgang Draf |

Fig. 14.3 Axial CT views showing persistent chronic frontal sinusitis, and demonstrating different AP dimensions of the frontal sinus ostium. Note also the dangerous frontal bone with protruding dura in the spine (asterisks). a Wide AP dimension. b Narrow AP dimension

steroids is used, which is also mandatory in postoperative care to prevent restenosis, leading to another disease recurrence. This is especially important for patients with more aggressive disease (i.e., aspirin triad patients).

14 In preparation for surgery, these patients regularly take 50 mg prednisone per day for the 10 immediately preoperative days.

Surgical Technique

Once revision surgery is indicated, careful individual planning is essential to decide whether the endonasal technique is still suitable or an external procedure should be preferred. In case of endonasal revision frontal sinus surgery, in our hands a stepwise progression from less (Draf’s type I or IIa/b drainages) to more invasive procedures (Draf’s type III drainage) has stood the test of time [6, 8, 9, 14, 18, 36]. For the Draf III drainage to be successful, special surgical equipment is necessary: 45° angled endoscope with irrigation and suction, angled instruments, suction irrigation drills (between 35° and 70°), and computer image guidance is often helpful.

General anesthesia is required for revision frontal sinus surgery. In addition, topical decongestion helps to provide a dry field. The nasal cavities are first decongested using topical xylometazoline, and then the septum and the lateral nasal wall at the agger nasi are injected with up to 12 ml of 1% lidocaine and 1:200,000 epinephrine solution. The extent and type of local decongestant applied depends on the medical condition of each individual patient.

Type I Drainage According to Draf

In general, prior to surgery on the frontal recess and sinus, at least an anterior, but better a complete ethmoidectomy has to be performed. It is important to remove all agger nasi cells. To minimize the risk of complications it is essential to visualize the attachment of the middle turbinate medially, the lamina papyracea laterally, and the anterior skull base with the anterior ethmoid artery superiorly. It should be kept in mind that in revision surgery the anatomy is significantly distorted and landmarks such as the middle turbinate may be partially resected, making them unreliable for anatomic localization. However, it should be remembered that the skull base is usually most easily identified in the posterior ethmoid or sphenoid sinus, where it is horizontal and the ethmoid cells are larger. Care always needs to be taken at the ethmoid roof near the anterior ethmoid artery and toward the attachment of the middle turbinate, as the skull base is thinnest in this area. Therefore, one should stay close and parallel to the lamina papyracea, opening one or two supraorbital ethmoid cells that are located anterior to the vessel. Once the frontal recess has been clearly identified, adjacent bony partitions can be fractured and teased out, which is as important as the preservation of mucosa. This opening corresponds to a simple drainage or type I drainage according to Draf (Fig. 14.4). An alternative when the middle turbinate has been retracted laterally due to previous surgery and is obstructing the frontal sinus drainage, is the so-called “frontal sinus rescue procedure” by Kuhn et al. [20].

Endoscopic and Microscopic Revision Frontal Sinus Surgery |

121 |

Fig. 14.4 Schematic illustration of a type I drainage according to Draf. The structures marked in red are those that have to be resected

Fig. 14.5 Schematic illustration of a type II drainage according to Draf. The structures marked in red are those that have to be resected

Type II Drainage According to Draf |

Type III Drainage According to Draf |

Type II drainage according to Draf (Fig. 14.5) is an extended drainage procedure that is achieved by resecting the floor of the frontal sinus between the lamina papyracea and the middle turbinate (type IIa) or the nasal septum (type IIb) anterior the ventral margin of the olfactory fossa either with the punch, curette, or with angled forceps [36]. Hosemann et al. [14, 15] showed in a detailed anatomical study that the maximum diameter of a neo-ostium of the frontal sinus (type IIa), which could be gained using a spoon or a curette, was 11 mm, with an average of 5.6 mm. If one needs to achieve a larger drainage opening like type IIb, one has to use a drill because of the increasing thickness of the bone going more medially toward the nasal septum. Care is needed to ensure that the frontal sinus opening is left bordered by bone on all sides and that the mucosa is preserved at least on one part of the circumference. In case one feels the type IIa drainage opening is too small with regard to the underlying pathology, it is better to perform the type IIb drainage. The wide approach to the ethmoid is obtained by exposing the lacrimal bone and reducing it as well as parts of the agger nasi and part of the frontal process of the maxilla until the lamina papyracea is clearly visible.

Type III drainage according to Draf (Fig. 14.6) is a median drainage procedure that involves removal of the upper part of the nasal septum and the lower part of the frontal sinus septum or septa, if there is more than one, in addition to the type IIb drainage of both frontal sinuses (Fig. 14.7). To achieve the maximum possible opening of the frontal sinus it is very helpful to identify the first olfactory fibers on both sides: the middle turbinate is exposed and cut, millimeter by millimeter, from anterior to posterior along its origin at the skull base. After about 10–15 mm one will see the first olfactory fiber coming out of a little bony hole. Finally, the so-called “frontal T” [7] results (Fig. 14.8). Its long crus is represented by the posterior border of the perpendicular ethmoid lamina resection, the shorter wings on both sides are provided by the posterior margins of the frontal sinus floor resection. This provides an excellent landmark for the anterior border of the olfactory fossa on both sides, which allows the completion of frontal sinus floor resection close to the first olfactory fiber. In difficult revision cases one can begin the type III drainage primarily from two starting points, either from the lateral side, as already described, or from medially. The primary lateral approach is recommended if the previous ethmoidectomy was incomplete and the middle turbinate is still present as a landmark.

122

|

Fig. 14.6 Schematic illustration of a type III drainage according |

|

to Draf. The structures marked in red are those that have to be |

|

resected |

|

One should adopt the primary medial approach if the |

14 |

|

|

ethmoid has been cleared and/or if the middle turbinate |

is absent. The primary medial approach begins with the partial resection of the perpendicular plate of the nasal

Ulrike Bockmühl and Wolfgang Draf

septum, followed by identification of the first olfactory fiber on each side, as already described. The endonasal median drainage corresponds with nasofrontal approach IV [23] and the “modified Lothrop procedure” [13].

The principle difference between the endonasal median frontal sinus drainage and the classic external operations according to Jansen [17], Lothrop [21], Ritter [27], Lynch [22], and Howarth [16] is that the bony borders around the frontal sinus drainage are preserved. This makes it more stable in the long term and reduces the likelihood of reclosure by scarring, which may lead to recurrent frontal sinusitis or a mucocele, not to mention the avoidance of an external scar.

As an external procedure, the osteoplastic obliterative frontal sinus operation is the gold standard in surgical treatment of a chronic inflammatory disease and the ultima ratio if a frontal sinus problem cannot be solved via the endonasal route. The decades-old “classic” external frontoethmoidectomy according to Jansen [17], Ritter [27], Lynch [22], or Howarth [16], achieved via an infraeyebrow incision, has to be judged as “obsolete” since the frequency of postoperative mucoceles increases with the duration of postoperative follow up, to 40% and more. The strategy of the osteoplastic obliterative operation is to remove very meticulously all mucosa of the frontal sinuses using a microscope and endoscope as visual aids. The naked eye is not sufficient! Ear cartilage and fascia are used to create a reliable barrier between the nose and ethmoid on one side and the frontal sinus on the other. Then the frontal sinuses have to be filled with freshly harvested

Fig. 14.7 Intraoperative condition after opening the frontal sinuses in the way of a type III drainage according to Draf (median drainage)

Fig. 14.8 Schematic illustration of the “frontal T” according to Draf. LC long crus, LFSF left frontal sinus floor, LP lamina perpendicularis, RFSF right frontal sinus floor, SC short crus

Endoscopic and Microscopic Revision Frontal Sinus Surgery |

123 |

Fig. 14.9 Conditions around the 7th postoperative day showing differences in wound healing. a Severe crusting. b Mild crusting with swollen mucosa

autogenic fat in smaller cubes. By this method the frontal sinuses are excluded from the paranasal sinus system [2]. In experienced hands the rate of postoperative mucocele does not exceed 10% [34].

Postoperative Care

Rubber finger stalls are used as nasal packages that will be left in place for 5 days in type III drainage and 3 days in type II drainages. Some authors advocated the use of soft, flexible silicone stents in cases of a frontal sinus neo-ostium less than 5 mm in diameter, since more rigid silicone tubes have not given satisfying results [26, 28, 37, 38]. So far, the techniques using soft silicone drainage devices have not shown promising results in long-term observations.

All patients with type III drainage are placed on postoperative antibiotics (our preferred choice is clarithromycin) for at least 5 days. After removing the packing, patients are instructed to perform nasal saline irrigations twice daily until healing is complete. The degree of crusting can be very different (Fig. 14.9). In general, leaving rubber finger stalls for longer reduces crusting because faster reepithelization is stimulated, like in a moistened chamber. In addition, all patients receive an intranasal steroid spray, and they are requested to use it for at least 3 months. Endoscopic debridement is performed in the office setting 1 and 2 weeks after surgery and is repeated every 2 weeks

thereafter until the crusting disappears. We achieve better results and less painful postoperative treatment by being less aggressive and removing only mobile crusts. Figure 14.10 shows an optimal postoperative result.

Fig. 14.10 Optimal result after type III drainage according to Draf (3 years postoperatively)

124

Patients with hyperplastic sinusitis and nasal polyposis, and aspirin triad patients may benefit from tapering doses of systemic oral steroids. We achieved positive effects by prescribing 5 mg prednisone daily for 30 days followed by 2.5 mg for another 40 days.

|

|

|

Outcomes and Complications |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Complications of endoscopic revision frontal sinus sur- |

|

|

|

gery: |

|

|

|

■ |

Frontal ostium restenosis. |

|

|

■ |

Orbital injury. |

|

|

■ |

Cerebrospinal fluid leakage. |

|

|

■ |

Intracranial injury. |

|

|

■ |

Bleeding. |

|

|

■ |

Crusting. |

|

|

Judging the results of endonasal frontal sinus surgery re- |

|

|

|

quires a postoperative follow up of several years, not only |

|

|

|

months [11, 24, 25, 30, 31]. Weber et al. [35, 36] carried |

|

|

|

out two retrospective studies evaluating the results of en- |

|

|

|

donasal frontal sinus drainages in cases of chronic polyp- |

|

|

|

oid rhinosinusitis after a mean follow up of 5 years (range |

|

|

|

1–12 years). All patients were examined by endoscopy |

|

|

|

and CT. In the first study, 132 patients from 1 institution |

|

14 |

|

were analyzed (42 type I, 43 type II, and 47 type III drain- |

|

|

|

ages). Applying subjective and objective criteria, they |

|

found a success rate of 85.7% in type I drainage, 83.8% in type II drainage, and 91.5% in type III drainage. In an updated survey the authors evaluated the results of three independent institutions summarizing 1286 patients (635 type I, 312 type II, and 156 type III drainages). They reported a primary patency rate of 85.2–99.3% in type I drainages, 79–93.3% in type II drainages, and 91.5–95% in type III drainages. This means that despite the choice of prognostically unfavorable cases, type III drainages appeared to show the best results, although this was not statistically significant among the three groups. Recently, Eviatar et al. [9] described a rate of ventilated frontal sinuses after type II drainages of 96% in 25 patients, with a mean follow up of 30 months. Batra et al. [1] presented surgical outcomes of “drill out procedures” for complex frontal sinus pathologies. Of 186 patients, 13.4% required type II or III drainages. Postoperatively, symptomatology was resolved in 32%, improved in 56%, and remained unchanged in 12% of the patients. Interestingly, endoscopic patency of the neo-ostium was noted in 92%.

Reviewing the results of the endoscopic modified Lothrop procedure, Gross et al. [13] found a 95% frontal drainage patency rate with a mean follow up of 12 months, but as experience with the procedure accumulated and patients were followed for longer periods

Ulrike Bockmühl and Wolfgang Draf

of time, the overall patency success rate was reduced. Schlosser et al. [29] followed 44 patients for an average of 40 months. Of these, 9 (20%) patients required revision modified Lothrop surgery and 8 (18%) eventually needed an osteoplastic frontal sinus operation with obliteration. Almost similar data are reported by Shirazi et al. [30], who analyzed 97 patients with a mean follow up of 18 months; 23% required revision surgery. In contrast, Wormald et al. [40] indicated a 93% primary patency rate with a mean follow up of 22 months. Recently, Friedman et al. [11] published the most comprehensive study evaluating 152 patients with a mean follow up of 72 months, and showing a 71.1% overall patency rate.

Regardless of the surgical procedure among 67 patients, Chiu and Vaughan [5] found 86.6% to have a patent frontal recess and significant subjective improvement in symptoms over an average follow up of 32 months.

Future Directions

Endonasal revision surgery of the frontal sinus remains a great challenge to all surgeons regardless of their experience. It requires proper training and special instruments. However, recurrent or persistent frontal sinus disease after surgery can be addressed with endoscopic or microscopic techniques with a high success rate and low complication rate. These techniques offer several advantages over frontal sinus obliteration and should be in every rhinologist’s armamentarium for use in the appropriate clinical situation. Only long-term follow up can determine whether the current endoscopic or microscopic methods will result in consistently permanently favorable results. Despite the progress in surgery, it remains the task to identify the underlying mechanisms causing chronic rhinosinusitis or triad and to develop appropriate medication to cure the disease.

Tips and Pearls

1.Sagittally reconstructed CT scans, especially indica ting the AP dimension, are required to assess patient’s candidacy for an endonasal revision procedure.

2.For anatomical orientation it is important to determine the presence of remaining agger nasi cells, the superior uncinate process, anterior ethmoid artery, bulla frontalis and supraorbital ethmoid cells, and the depth of the olfactory fossa.

3.When drilling, care has to be taken to preserve the mucosa on the lateral and posterior wall of the frontal recess in order to prevent complications and postoperative stenosis.

Endoscopic and Microscopic Revision Frontal Sinus Surgery |

125 |

4.A large resection of the upper nasal septum is required to provide adequate drainage of the frontal sinuses, and to avoid restenosis.

5.Preand postoperative medical management support wound healing, and regular surveillance should be carried out to assure surgical outcome and prevent disease recurrence.

References

1.Batra PS, Cannady SB, Lanza DC (2007) Surgical outcomes of drillout procedures for complex frontal sinus pathology. Laryngoscope 117:927–931

2.Bockmühl U (2005) Osteoplastic frontal sinusotomy and reconstruction of frontal defects. In: Kountakis S, Senior B, Draf W (eds) The Frontal Sinus. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 281–289

3.Bradley DT, Kountakis SE (2004) The role of agger nasi air cells in patients requiring revision endoscopic frontal sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 131:525–527

4.Chandra RK, Palmer JN, Tangsujarittham T, Kennedy DW (2004) Factors associated with failure of frontal sinusotomy in the early follow-up period. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 131:514–518

5.Chiu AG, Vaughan WC (2004) Revision endoscopic frontal sinus surgery with surgical navigation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 130:312–318

6.Draf W (1991) Endonasal micro-endoscopic frontal sinus surgery. The Fulda concept. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2:134–240

7.Draf W (2005) Endonasal frontal sinus drainage type I-III according to Draf. In: Kountakis S, Senior B, Draf W (eds) The Frontal Sinus. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 219-232

8.Draf W, Weber R, Keerl R, Constantinidis J, Schick B, Saha A (2000) Endonasal and external micro-endoscopic surgery of the frontal sinus. In: Stamm A, Fraf W (eds) Microendoscopic Surgery of the Paranasal Sinuses and the Skull Base. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp 257–278

9.Eviatar E, Katzenell U, Segal S, Shlamkovitch N, Kalmovich LM, Kessler A, Vaiman M (2006) The endoscopic Draf II frontal sinusotomy: non-navigated approach. Rhinology 44:108–113

10.Farhat FT, Figueroa RE, Kountakis SE (2005) Anatomic measurements for the endoscopic modified Lothrop procedure. Am J Rhinol 19:293–296

11.Friedman M, Bliznikas D, Vidyasagar R, Joseph NJ, Landsberg R (2006) Long-term results after endoscopic sinus surgery involving frontal recess dissection. Laryngoscope 116:573–579

12.Gross CW, Schlosser RJ (2001) The modified Lothrop procedure: lessons learned. Laryngoscope 111:1302–1305

13.Gross WE, Gross CW, Becker D, Moore D, Phillips D (1995) Modified transnasal endoscopic Lothrop procedure as an alternative to frontal sinus obliteration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 113:427–434

14.Hosemann W, Gross R, Goede U, Kuehnel T (2001) Clinical anatomy of the nasal process of the frontal bone (spina nasalis interna). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 125:60–65

15.Hosemann W, Kuhnel T, Held P, Wagner W, Felderhoff A (1997) Endonasal frontal sinusotomy in surgical management of chronic sinusitis: a critical evaluation. Am J Rhinol 11:1–9

16.Howarth WG (1921) Operations on the frontal sinus. J Laryngol Otol 36:417–421

17.Jansen A (1894) Zur Eröffnung der Nebenhöhlen der Nase bei chronischer Eiterung. Arch Laryng Rhinol (Berl) 1:135–157

18.Kennedy DW, Senior BA (1997) Endoscopic sinus surgery. A review. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 30:313–330

19.Kountakis S (2005) Endoscopic modified Lothrop procedure. In: Kountakis S, Senior B, Draf W (eds) The Frontal Sinus. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 233–241

20.Kuhn FA, Javer AR, Nagpal K, Citardi MJ (2000) The frontal sinus rescue procedure: early experience and three-year follow-up. Am J Rhinol 14:211–216

21.Lothrop HA (1914) Frontal sinus suppuration. Ann Surg 29:175–215

22.Lynch RC (1921) The technique of a radical frontal sinus operation which has given me the best results. Laryngoscope 31:1–5

23.May M (1991) Frontal sinus surgery: endonasal endoscopic osteoplasty rather than external osteoplasty. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2:247–256

24.Neel HB 3rd, McDonald TJ, Facer GW (1987) Modified Lynch procedure for chronic frontal sinus diseases: rationale, technique, and long-term results. Laryngoscope 97:1274–1279

25.Orlandi RR, Kennedy DW (2001) Revision endoscopic frontal sinus surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 34:77–90

26.Rains BM 3rd (2001) Frontal sinus stenting. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 34:101–110

27.Ritter G (1906) Eine neue Methode zur Erhaltung der vorderen Stirnhöhlenwand bei Radikaloperationen chronischer Stirnhöhleneiterungen. Dtsch Med Wschr 19:905–907

28.Schaefer SD, Close LG (1990) Endoscopic management of frontal sinus disease. Laryngoscope 100:155–160

29.Schlosser RJ, Zachmann G, Harrison S, Gross CW (2002) The endoscopic modified Lothrop: long-term follow-up on 44 patients. Am J Rhinol 16:103–108