- •Dedication

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Figure Credits

- •Expert Consultants and Reviewers

- •Contents

- •Descriptive Terms for Normal Cells

- •Descriptive Terms for Abnormal Cells and Tissues

- •Epithelium

- •Glands

- •Introduction and Key Concepts for Connective Tissue

- •Cartilage

- •Bone

- •Introduction and Key Concepts for the Nervous System

- •Peripheral Blood Cells

- •Hemopoiesis

- •Introduction and Key Concepts for the Circulatory System

- •The Cardiovascular System

- •Introduction and Key Concepts for the Lymphoid System

- •Cells in the Lymphoid System

- •Introduction and Key Concepts for the Respiratory System

- •Conducting Portion

- •Respiratory Portion

- •Introduction and Key Concepts for the Urinary System

- •Introduction and Key Concepts for the Integumentary System

- •Oral Mucosa

- •Teeth

- •Introduction and Key Concepts for the Digestive Tract

- •Introduction and Key Concepts for the Endocrine System

- •Introduction and Key Concepts for the Male Reproductive System

- •Introduction and Key Concepts for the Female Reproductive System

- •Introduction and Key Concepts for the Eye

- •Introduction and Key Concepts for the Ear

- •Introduction

- •Preservation versus Fixation

- •Fixatives and Methods of Fixation

- •Sectioning and Mounting

- •Staining

- •Index

CHAPTER 14 ■ Oral Cavity |

257 |

|

Tooth Development (Odontogenesis) |

|

|

Figure 14-8 |

Overview of Tooth Development (Odontogenesis) |

|

Figure 14-9A |

Bud Stage, Weeks 8–9 |

|

Figure 14-9B |

Cap Stage, Weeks 10–11 |

|

Figure 14-10A |

Bell Stage, Weeks 12–14 |

|

Figure 14-10B |

Bell Stage, Cell Layers |

|

Figure 14-11A |

Apposition (Crown) Stage, Dentinogenesis |

|

Figure 14-11B |

Apposition (Crown) Stage, Amelogenesis |

|

Figure 14-12A |

Tooth Root Development |

|

Figure 14-12B |

Tooth Eruption |

|

Figure 14-12C |

Clinical Correlation: Dilaceration |

|

Figure 14-13A |

Clinical Correlation: Gemination, Incisor |

|

Figure 14-13B |

Clinical Correlation: Amelogenesis Imperfecta |

|

Figure 14-13C |

Clinical Correlation: Enamel Pearl |

|

Enamel, Dentin, and Dental Pulp |

|

|

Figure 14-14A,B |

Enamel, Tooth |

|

Figure 14-14C |

Clinical Correlation: Enamel Fluorosis |

|

Figure 14-15A,B |

Dentin, Tooth |

|

Figure 14-15C |

Clinical Correlation: Dentinogenesis Imperfecta |

|

Figure 14-16A |

Clinical Correlation: Vitamin D–Resistant Rickets |

|

Figure 14-16B |

Clinical Correlation: Dentin Dysplasia |

|

Table 14-3 |

Dental Hard Tissue |

|

Figure 14-17A,B |

Dental Pulp |

|

Figure 14-17C |

Clinical Correlation: Pulp Abscess |

|

Periodontium |

|

|

Figure 14-18A |

Acellular Cementum, Cervical Region of Tooth Root |

|

Figure 14-18B |

Cellular Cementum, Apical Region of Tooth Root |

|

Figure 14-18C |

Periodontal Ligament and Alveolar Bone |

|

Figure 14-19A |

Periodontal Ligament and Alveolar Bone, Tooth Root |

|

Figure 14-19B |

Clinical Correlation: Tooth Ankylosis |

|

Synopsis 14-1 |

Pathological and Clinical Terms for the Oral Cavity |

|

Oral Mucosa

Introduction and Key Concepts for Oral Mucosa

The oral cavity refers to the internal part of the mouth and can be divided into the oral vestibule and the oral cavity proper. The oral vestibule is the space between the inner lips, cheeks, and front surface of the teeth. The oral cavity proper is the space between the upper and lower dental arches, extending from the inner surface of the teeth to the oropharynx. The structures inside of the oral cavity include the lips, cheeks, tongue, teeth, gingiva, palates (hard and soft), salivary glands, and tonsils. The tonsils are discussed in Chapter 10, “Lymphoid System,” and salivary glands are discussed in Chapter 16, “Digestive Glands and Associated Organs.” The structures in the oral cavity are lined by an oral mucosa, which includes an overlying epithelium and underlying connective tissue. The oral mucosa can be

divided into three types based on differences in the epithelial covering, organization of the connective tissue, and associated functions: lining, masticatory, and specialized mucosa.

LINING MUCOSA is covered by nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with two distinct layers: the stratum basale and stratum spinosum. The epithelium of the lining mucosa is similar to the epidermis of the skin, except that it has neither a stratum corneum nor a stratum lucidum, and the stratum granulosum is often absent (see Chapter 13, “Integumentary System,” Figs. 13-2 and 13-3B). The nonkeratinized stratified epithelium is moistened by saliva. The connective tissues of the lining mucosa can be divided into the lamina propria and the submucosa. The lamina propria is a thin layer of loose connective tissue containing many elastic fibers and relatively few collagen fibers. This layer is equivalent to the dermis of the skin and is located beneath the epithelium. The submucosa is a thick layer of connective tissue, which contains minor salivary

258 UNIT 3 ■ Organ Systems

glands and is attached to the underlying muscle. The lining mucosa covers the inner oral surfaces of the lips, cheeks, soft palate, the inferior surface of the tongue, and the floor of the mouth. This type of mucosa is less exposed to abrasion than the masticatory mucosa. The lining mucosa provides a barrier against the invasion of pathogens and toxic chemicals, contains receptors for sensations, and serves immunological functions. The lining mucosa also provides lubrication and buffering by minor glands in the submucosal layer. Examples of the lining mucosa include the lip (Fig. 14-2D) and cheek (Fig. 14-3A).

MASTICATORY MUCOSA is covered by keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, which is exposed to significant abrasion due to high compression and friction during chewing. The epithelium of the masticatory mucosa is composed of the stratum basale, stratum spinosum, stratum granulosum, and stratum corneum. It has a thick lamina propria that contains a dense network of collagen fibers and a few elastic fibers. This layer has no submucosa and is directly and firmly attached to the underlying bone. Masticatory mucosa can be found covering the oral surfaces of the gingiva and the hard palate. Injection into this area is difficult and painful because of its sensitive periosteum, high collagen density, and firm attachment to the bone. See Figure 14-4A for examples of the gingiva and Figure 14-4B for the hard palate.

SPECIALIZED MUCOSA covers the anterior two thirds of the tongue and consists of keratinized and nonkeratinized squamous epithelium and numerous papillae. These papillae can be classified into four types: filiform, fungiform, circumvallate, and foliate papillae. Most of these papillae have taste buds. The filiform papillae are the only papillae without taste buds; their main function is to aid in mixing food during chewing. The lamina propria (connective tissue) of the specialized mucosa is attached to the underlying skeletal muscle. These muscles produce voluntary movement of the tongue and are innervated by the hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve [CN] XII).

Lining mucosa covers the inferior surface of the tongue. The mucosa of the tongue is divided into two parts by a V-shaped groove called the sulcus terminalis. The anterior two thirds of the tongue is referred to as the body of the tongue. Its mucosa is innervated by the facial nerve (CN VII) and the trigeminal nerve (CN V). The posterior third of the tongue is the base of the tongue. Its taste buds and mucosa are innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX). The posterior third of the tongue contains the lingual tonsils (Fig. 14-5A).

1.Filiform papillae are the smallest and most numerous of the four types of papillae. They cover almost the entire superior surface of the anterior two thirds of the tongue and are packed in rows that parallel the sulcus terminalis. Each of the papillae appears cone shaped with some branching processes. Connective tissue forms the central core of each papilla. Filiform papillae have no taste buds and extend from the nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The surface of the papilla is keratinized and is exposed to a great deal of abrasion (Fig. 14-5B).

2.Fungiform papillae are less numerous than the filiform papillae. They are mushroom shaped and are scattered among the filiform papillae (Fig. 14-5C). Fungiform papillae are located at the tip and on the two lateral edges of the tongue. They are more numerous near the tip of the tongue. Taste buds are found on the apical surfaces of fungiform papillae.

3.Circumvallate papillae are large and round with a flattopped cylindrical structure. There are about 10 to 14 papillae arranged in a row along the sulcus terminalis. Each papilla is surrounded by a deep groove (moat), which forms a valley around the papilla. Taste buds are found in the lateral walls of each papilla (Fig. 14-6A).

4.Foliate papillae are leaflike folds with flat tops and have deep clefts between the papillae. They are located on the posterior lateral surface of the tongue. They are more prominent in some animals (such as rabbits) than in humans. Foliate papillae contain taste buds in the lateral walls of the papillae (Fig. 14-6B).

CHAPTER 14 ■ Oral Cavity |

259 |

Gingiva |

Dentogingival |

|

|

(masticatory mucosa) |

junction |

Dentin Enamel |

|

Mucogingival |

|

|

|

Labialjunction(lining) |

|

|

|

mucosa |

|

|

|

Labial (lining) |

|

|

|

mucosa |

|

|

|

Vermilion zone |

|

|

|

(intermediate zone |

|

crown |

crown |

junction) |

|

||

mucocutaneous |

|

|

|

|

|

l |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Clinical |

a |

|

|

Anatomic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Skin |

|

susulcuscLabial lus abalil |

|

Gingiva sulcus |

|

epithelium |

Dental pulp |

|

|

Enamel |

|

Gingiva |

|

Free gingiva |

space |

Sulcus |

|

|

Gingival |

|

|

|

|

epithelium |

|

|

|

|

Crown

Cervix

Root

Root

Junctional

epithelium

Apical foramen

Alveolar |

|

|

Alveolar bone |

Dentin |

Alveolar (lining) |

(process) |

|

bone |

|

mucosa |

|

Figure 14-1. Overview of the oral mucosa and teeth. Lower left, H&E, 18

The oral cavity is lined by oral mucosa, which can be divided into masticatory mucosa (gingiva, hard palate), lining mucosa (lips, soft palate, cheeks, inferior surface of the tongue, floor of the mouth), and specialized mucosa (tongue). This illustration represents the lip and a tooth and the mucosa covering these structures. The lip is covered externally with skin to the vermilion zone (intermediate zone or mucocutaneous junction); the vermilion zone continues to the labial mucosa, which is the lining mucosa on the internal surface of the lip. The alveolar process of the jaw (containing the tooth roots) is covered by alveolar mucosa (lining mucosa) and gingiva. The junction between the lining mucosa and gingiva is the mucogingival junction. The tooth can be divided into three parts: crown, cervix, and root. The crown is the part of the tooth projecting into the oral cavity and has two different definitions: The clinical crown is the part of the crown which is visible in the mouth; the anatomical crown is the part of the tooth covered by enamel. The root is covered by the gingiva or is inside the bony socket. The region between the crown and root is the cervix (neck). The gingival sulcus is the space between the free gingiva and the enamel; it is normally 0.5 to 3.0 mm in depth.

If the depth of the gingival sulcus is over 3 mm, these spaces are called gingival or periodontal pockets. These pockets represent an abnormal condition. An accumulation of debris and microbes in the pockets may cause damage to the periodontal ligament (PDL). For tooth details, see Figure 14-7.

Structures of the Oral Mucosa

I.Lining mucosa (covering of inner surface of the lips and cheeks, soft palate, inferior surface of the tongue, and floor of the mouth)

A.Epithelium: nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium

B.Lamina propria: connective tissue with many elastic fibers and few collagen fibers

C.Submucosa: connective tissue with minor salivary glands and their ducts

II.Masticatory mucosa (covering of gingiva and hard palate) A. Epithelium: keratinized stratified squamous epithelium

B.Lamina propria: connective tissue with few elastic fibers and many dense collagen fibers

C.No submucosa

III. Specialized mucosa (tongue)

A.Filiform papillae: no taste buds

B.Fungiform papillae: taste buds on apical surface of the papilla—sweet, sour, salty

C.Circumvallate papillae: taste buds in lateral wall of the papilla—bitter

D.Foliate papillae: taste buds in lateral wall of papilla

260 UNIT 3 ■ Organ Systems

Lining Mucosa

A |

|

Fig. |

|

Vermilion |

|

|

|

zone |

|

|

Vermilion |

14-2C |

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

zone |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Orbicularis |

|

|

|

|

oris muscle |

|

|

Fig. |

|

|

muscle |

|

|

|

|

|

Skin |

14-2B |

|

Orbicularisoris |

|

|

|

|

||

Minor salivary gland

Labial (lining) mucosa

Fig.

Fig.

14-2D

B |

Sebaceous |

|

|

||

Hair |

glands |

|

|

||

follicle |

|

|

space |

Sweat |

|

|

||

|

glands/ducts |

|

Hair |

Sebaceous |

|

glands |

||

follicle |

||

|

Epidermis |

Dermis |

Sweat |

|

|

glands/ducts |

Figure 14-2A. Overview of the lip, H&E, 7.6

Lining mucosa is a wet mucosa that covers the inside of the mouth and is lined by nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The labial mucosa of the lip is an example of lining mucosa. The lips are soft, flexible, and movable; they play important roles in food intake, speech, and as a sensory organ (e.g., kissing). Lips can be divided into three regions: (1) thin skin, forming the external surface of the lip; (2) vermilion zone, appearing red in color, also called the intermediate zone or mucocutaneous junction; and (3) the labial mucosa (lining mucosa), the internal surface of the lip. The central core of the lip contains the orbicularis oris (skeletal) muscle, which is innervated by the facial nerve (CN VII), and contributes to lip movement and facial expressions.

Figure 14-2B. Skin, lip. H&E, 33; inset 44

An example of the skin on the external surface of the lip is shown. It is covered by keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The sebaceous glands in the dermis are associated with hair follicles, and sweat glands are present. The skin of the lip is like thin skin elsewhere and can be divided into epidermis and dermis.

Figure 14-2C. Vermilion zone, lip. H&E, 33

The vermilion zone of the lip is covered by parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. Sebaceous-like glands (Fordyce granules or spots) may be found in the connective tissue and are not associated with hair follicles. These glands have ducts that release their oily product directly onto the surface of the lip. The vermilion zone appears red because of many blood vessels near the surface of the thin and translucent epithelium (Fig. 14-1). This region can become thick and forms the sucking pad in infants.

Figure 14-2D. Labial mucosa (lining mucosa), lip. H&E, 33

The labial mucosa of the lip is an example of lining mucosa, which is covered by nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium and contains many elastic fibers; it is very flexible and can be stretched. Its submucosa layer contains many minor salivary glands (mucous glands). The minor salivary glands in the lips are often called labial glands.

C |

Parakeratinized stratified |

D |

|

squamous epithelium |

|

|

|

Nonkeratinized stratified |

Stratum |

|

spinosum |

||

squamous epithelium |

||

Stratum |

||

|

||

|

basale |

|

Ducts of sebaceous-like |

Ducts of minor |

Fordyce granules/spots |

glands |

salivary glands |

(sebaceous-like glands) |

|

Minor |

|

|

|

|

|

salivary |

|

|

glands |

|

|

|

CHAPTER 14 ■ Oral Cavity |

261 |

Nonkeratinized stratified |

|

|

Figure 14-3A. |

Buccal mucosa (lining mucosa), cheek. |

Stratum |

|

H&E, 16 |

|

|

squamous epithelium |

|

|

|

|

|

granulosum |

|

Each cheek constitutes a lateral wall of the mouth. The inner |

|

|

|

|

||

Stratum |

|

|

surface of the cheeks is lined by lining mucosa known as buccal |

|

|

|

mucosa. The buccal mucosa has a nonkeratinized stratified |

||

spinosum |

|

|

||

|

|

squamous epithelium with three definite layers (stratum basale, |

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

spinosum, and granulosum) with many elastic fibers in the |

|

|

|

|

lamina propria and minor salivary glands (buccal glands) in the |

|

|

|

|

submucosa layer. This example shows the epithelium and lam- |

|

Stratum |

|

|

ina propria of the buccal mucosa, which has a nonkeratinized |

|

basale |

|

|

stratified squamous epithelium. There are many elastic fibers in |

|

|

|

|

the lamina propria of the mucosa. Elastic fibers appear pink and |

|

Lamina |

|

|

do not readily stain with H&E stain. Fordyce spots (sebaceous- |

|

propria |

|

Elastic fibers |

like glands) may also be found in the mucosa of the cheek. They |

|

|

|

increase with age and are more visible in elderly individuals. |

||

|

|

|

||

A |

|

The lingual and inferior alveolar nerves run through the pos- |

|

|

|

|

|

terior groove of the cheek (between the pterygomandibular |

|

||

|

|

raphe and the ramus of the mandible). This is an important |

|

|

landmark for local anesthesia injections in the mouth. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CLINICAL CORRELATION

B

Atrophic epithelium

Increased  collagen fibers

collagen fibers

Figure 14-3B. Oral Submucous Fibrosis of the Lip.

H&E, 25

Oral submucous fibrosis is a precancerous condition characterized by a mucosal rigidity due to fibroelastic changes of the lamina propria and submucosa layers of the lining mucosa. This causes a progressive difficulty in opening the mouth. It affects the buccal mucosa, lips, retromolar areas, the soft palate, and even the esophagus. Causes of this condition include the use of chillies and areca nut, collagen disorders, and autoimmune disorders. Histologically, it is characterized by atrophic (thinned) epithelium and increased collagen fiber formation followed by the presence of dense collagen fiber bundles and different degrees of hyalinization. Prevention and treatments of the disease include dietary changes and having plastic surgery to improve the function of the mouth.

TABLE 14 - 1 Comparison of Lining and Masticatory Mucosae

Name of |

Epithelium |

Lamina Propria |

Submucosa |

Covering |

Special |

Clinical Application |

Mucosa |

|

|

|

Region |

Features |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lining |

Nonkeratinized |

Few collagen |

Well-developed |

Lips, cheeks, |

Thick, soft, |

Injections are easy to |

mucosa |

stratified |

fibers; many |

submucosa; |

soft palate, |

and loose; |

make and minimally |

|

squamous |

elastic fibers |

attached |

inferior surface |

flexible |

painful; if cut, a gap |

|

epithelium |

|

primarily to |

of the tongue, |

and can be |

appears that requires |

|

|

|

underlying muscle |

and floor of the |

stretched |

suturing; infection |

|

|

|

rather than |

mouth |

|

spreads quickly |

|

|

|

bone (except for |

|

|

|

|

|

|

alveolar mucosa) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Masticatory |

Keratinized |

Dense network |

No submucosa |

Gingiva, hard |

Thin, stiff, |

Injections are difficult |

mucosa |

stratified |

of collagen fibers; |

present; lamina |

palate |

dense; |

and painful; if cut, |

|

squamous |

few elastic fibers |

propria is directly |

|

cannot be |

no gap results and |

|

epithelium |

|

and firmly bound |

|

stretched |

suturing is not |

|

|

|

to the bone |

|

|

necessary; infection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

spreads slowly |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

262 UNIT 3 ■ Organ Systems

Masticatory Mucosa

A |

|

Sulcus epithelium |

|

|

Free |

|

Enamel space |

|

|

gingiva |

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Junction epithelium |

|

|

|

|

Cementum |

|

|

Attached |

propria |

|

|

|

gingiva |

Dentin |

Dental |

||

|

||||

|

|

|

||

|

Lamina |

|

pulp |

|

|

Alveolar bone |

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

Mucogingival |

|

|

Alveolar |

|

junction |

|

|

mucosa |

|

|

|

Figure 14-4A. Masticatory mucosa, gingiva. H&E, 22

Masticatory mucosa covers the gingiva and hard palate; it has a keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, which is exposed to more abrasion during chewing than the lining mucosa. Masticatory mucosa lacks a submucosa layer. The lamina propria of the masticatory mucosa consists of a dense network of collagen fibers that are firmly attached to the underlying bone. The gingiva (gum) surrounds the cervix of the tooth and covers the upper part of the alveolar bone at the tooth root. The gingiva can be divided into free gingiva and attached gingiva. The superior part of the gingiva is free gingiva and surrounds, but does not attach to, the cervix of the tooth. This nonattachment between the sulcus epithelium of the free gingiva and enamel creates a space called the gingival sulcus, or free gingival groove, (normally 0.5–3 mm depth). The attached gingiva firmly attaches to the underlying hard tissues (alveolar bone, cementum, and edge of the enamel). The gingival-mucosal border is called the mucogingival junction (see Fig. 14-1), where the epithelium changes from nonkeratinized to keratinized and the color changes from bright pink (alveolar mucosa) to pale pink (gingiva).

Keratinized stratified |

Stratum corneum |

squamous epithelium |

|

Stratum spinosum

Stratum  granulosum Stratum

granulosum Stratum

basale

Lamina

propria Collagen fibers

B

Figure 14-4B. Masticatory mucosa, hard palate. H&E, 35

The hard palate forms the roof of the mouth and is covered by masticatory mucosa with keratinized stratified squamous epithelium and a dense lamina propria. It has one more layer (stratum corneum) than the lining mucosa. The collagen fibers in the lamina are thick and dense and firmly bind to the periosteum of the underlying bone. The periosteum consists of dense connective tissue, which covers the bone and contributes to bone formation (see Chapter 5, “Cartilage and Bone,” Fig. 5-10B). Most of the hard palate lacks a submucosal layer. However, the posterior region near the alveolar process may present a submucosal layer that contains minor mucous glands. The hard palate significantly assists in mastication and speech.

Cleft palate is a birth defect in which there is a fissure in the hard palate that is caused by the failure of two parts of the palate to fuse during facial development. This condition impairs the quality of speech (an individual is unable to pronounce certain sounds) and also causes eating problems.

CLINICAL CORRELATION

Hyperkeratosis

Acanthosis

Acanthosis |

Orifice of the |

|

gland ducts |

C |

Minor salivary |

glands |

Figure 14-4C. Nicotine Stomatitis. H&E, 25

Nicotine stomatitis is a nonprecancerous condition characterized by a white lesion in the oral mucosa of the hard palate of the mouth. The causes of this condition are associated with longterm tobacco smoking, especially pipe smoking, and hot beverage consumption. The lesion has a white cobblestone or “driedmud” appearance because of excessive keratin production. The hard palate may appear gray or white and contain many papules that are slightly elevated with red in their center. Histologically, the squamous mucosa demonstrates hyperkeratosis (thickening of the stratum corneum) and acanthosis (overgrowth of the stratum spinosum). Complete smoking cessation usually helps to diminish and resolve the condition within about two weeks. If the lesion persists, close monitoring may be necessary.

CHAPTER 14 ■ Oral Cavity |

263 |

Specialized Mucosa

|

Lingual |

Oropharynx |

tonsil |

|

|

|

Palatine |

|

tonsil |

Palatoglossus |

|

muscle |

|

Sulcus |

|

terminalis |

Foliate |

|

|

Fig. 14-6A |

papillae |

Fig. 14-5B |

Circumvallate |

|

|

Filiform |

papillae |

papillae |

|

|

Fungiform |

|

papillae |

A |

T. Yang |

Fig. 14-5C |

Figure 14-5A. Overview of the tongue.

The inferior surface of the tongue and the floor of the mouth are covered by lining mucosa with a nonkeratinized squamous epithelium. The superior surface of the tongue is covered by specialized mucosa with numerous projecting papillae including filiform papillae, fungiform papillae, circumvallate papillae, and foliate papillae. The specialized mucosa is attached to the underlying skeletal muscle. The tongue has a central core of skeletal muscle, which controls movements of the tongue and is innervated by the hypoglossal nerve (CN XII). The base of the tongue is attached to the floor of the mouth. The surface of the posterior third of the tongue has somatosensory receptors and taste buds that are innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX). The anterior two thirds of the tongue has somatosensory receptors that are innervated by the trigeminal nerve (CN V), and its taste buds are innervated by the facial nerve (CN VII). The tongue plays an important role in speech, taste, and in moving and swallowing (deglutition) food.

Filiform papillae

|

Epithelium |

Lamina |

propria |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

B |

|

|

Skeletal |

|

|

muscle |

Figure 14-5B. Filiform papillae, tongue. H&E, 35

The filiform papillae are slender, cone-shaped papillae with keratinized outer surfaces. They are the most numerous but smallest in size of the four types of papillae. The filiform papillae are often packed in rows and cover the entire superior surface of the anterior two thirds of the tongue (anterior to the sulcus terminalis). Each filiform papilla has a central connective tissue core with several branches of small papillae. They are the only papillae that do not have taste buds. The filiform papillae’s tips are keratinized, consistent with their exposure to abrasion during chewing. Because they have no taste buds, their main functions are to help with chewing and mixing food. The submucosal layer is absent in the tongue; the mucosa of the tongue is strongly bound to the underlying skeletal muscle to allow optimum food bolus control.

Fungiform papilla

Filiform papillae

Epithelium

Lamina |

propria |

|

Skeletal muscle

Figure 14-5C. Fungiform papillae, tongue. H&E, 44

The fungiform papillae are mushroom shaped and much less numerous than the filiform papillae. They tend to be slightly taller than the filiform papillae that surround them. Each fungiform papilla has one to five taste buds on its superior surface. These taste buds are innervated by the chorda tympani branch of the facial nerve (CN VII), which joins the lingual branch of the trigeminal nerve (CN V). The fungiform papillae are covered by nonkeratinized squamous epithelium. They are distributed at the tip and two sides of the tongue (Fig. 14-5A). In general, the taste buds have five taste sensations: sweet, bitter, umami, salty, and sour. The salty and sour sensations are associated with ion channels; the other three taste sensations are associated with G protein–coupled receptors.

C

264 UNIT 3 ■ Organ Systems

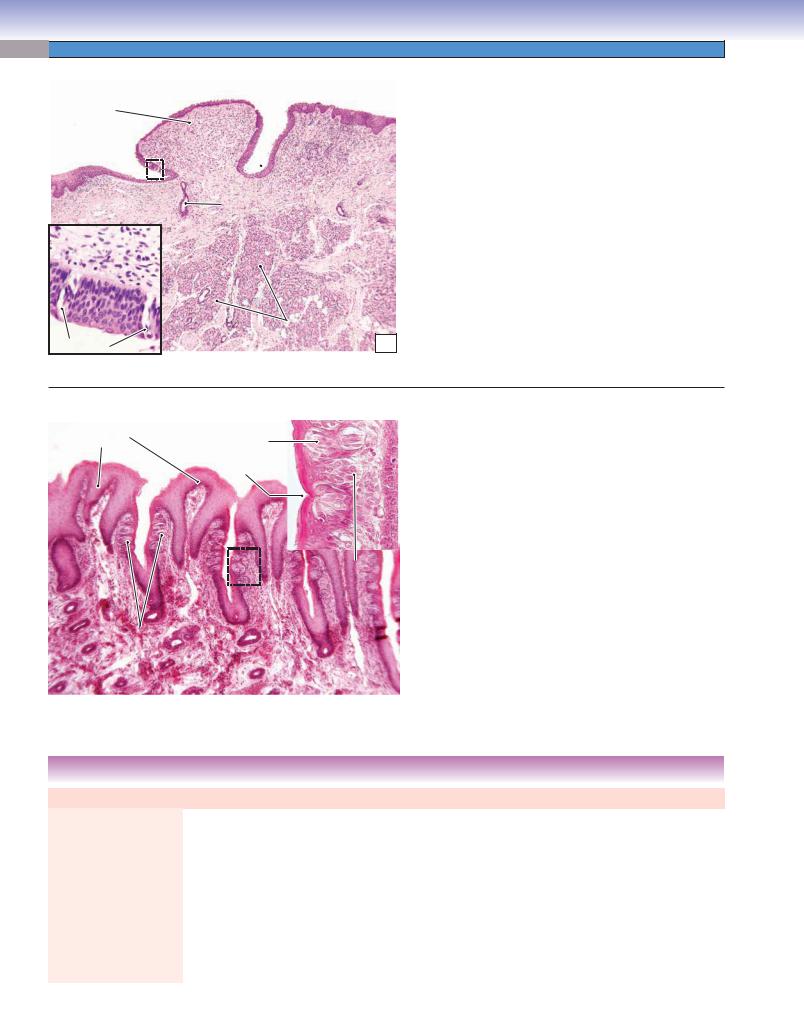

Circumvallate |

Figure 14-6A. |

Circumvallate papillae, tongue. H&E, |

34 inset 181 |

|

|

papilla |

|

|

Lateral wall

(taste buds)

(taste buds)

Moat (groove)

Moat (groove)

Duct of the

Von Ebner glands

|

Von Ebner |

|

glands |

Taste buds |

A |

The circumvallate papillae are also called vallate papillae. They are arranged in a single row, which contains about 10 to 14 papillae that are located immediately anterior to the sulcus terminalis (Fig. 14-5A). Each circumvallate papilla is cylindrical in shape and is surrounded by a groove called a moat. The ducts of the glands of von Ebner (minor serous salivary glands) open and drain serous products into the groove; this helps to clear the food debris in the groove and helps in detection of taste. Most minor salivary glands in the oral cavity are mucous or mixed glands; von Ebner glands are the only ones that are pure serous glands. The taste buds of the circumvallate papillae are located on the lateral walls of the groove. These taste buds are mainly bitter receptors and are innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX).

Foliate |

Taste receptor cell |

|

|

|

Figure 14-6B. |

Foliate papillae and taste buds, tongue. |

papilla |

|

|

|

H&E, 68 inset |

222 |

|

|

Taste pore |

|

|

|

The foliate papillae are located on the posterior lateral |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

surface of the tongue. This type of papilla is not well devel- |

||

|

|

|

|

oped in humans but is frequently found in animals; illus- |

||

|

|

|

|

trated here from rabbit tissue. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

In general, taste buds are ovular structures embedded |

|

|

|

|

|

in nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium of the |

||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Basal cell |

papillae of the tongue. They also can be found in the pal- |

|||

|

|

ate of the oral cavity and in the mucosa of the oropharynx |

||||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

and epiglottis. Each taste bud is composed of 40 to 60 elon- |

||

|

|

|

|

gated taste receptor cells with microvilli at the apical region, |

||

|

|

|

|

which extend into the taste pore. The basal end of the taste |

||

Taste buds |

|

|

|

bud contacts an afferent nerve fiber. The taste pore is a small |

||

|

|

|

|

opening that allows taste molecules to contact taste recep- |

||

|

|

|

|

tor cells. The taste receptor cells have a life span of 1 to |

||

|

|

|

|

2 weeks, and new taste cells arise from basal cells at the basal |

||

|

|

|

B |

|||

|

|

|

lateral region of the taste bud. The inset shows taste buds. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TABLE 14 - 2 Comparison of Lingual Papillae

Name |

Epithelial Covering |

Taste Buds |

Location |

Main Function |

Filiform papillae |

Keratinized stratified |

No taste buds |

Anterior 2/3 of tongue |

Helps in chewing and |

|

squamous epithelium |

|

|

mixing food |

Fungiform papillae |

Nonkeratinized stratified |

Taste buds located at |

Tip and two sides of |

Chemoreceptor |

|

squamous epithelium |

the apical surface of |

tongue |

detecting taste |

|

|

papillae |

|

|

Circumvallate papillae |

Nonkeratinized stratified |

Taste buds located at |

In a V-shaped row just |

Chemoreceptor |

|

squamous epithelium |

the lateral surface of |

anterior to the sulcus |

detecting taste |

|

|

papillae |

terminalis |

|

Foliate papillae |

Nonkeratinized stratified |

Taste buds located at |

Posterior lateral |

Chemoreceptor |

|

squamous epithelium |

the lateral surface of |

surface of the tongue |

detecting taste |

|

|

papillae |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|