- •CONTENTS

- •PREFACE

- •Content—Benefits for Students

- •Content—Benefits for Instructors

- •Features of the Book for Students and Instructors

- •Supplementary Materials

- •Acknowledgments

- •What Is Hospitality Management?

- •The Manager’s Role in the Hospitality Industry

- •Why Study in a Hospitality Management Program?

- •Planning a Career

- •Employment as an Important Part of Your Education

- •Getting a Job

- •Employment at Graduation

- •The Outlook for Hospitality

- •Summary

- •Managing Change

- •Demand

- •Supply

- •Workforce Diversity

- •The Impact of Labor Scarcity

- •Summary

- •The Varied Field of Food Service

- •The Restaurant Business

- •The Dining Market and the Eating Market

- •Contemporary Popular-Priced Restaurants

- •Restaurants as Part of a Larger Business

- •Summary

- •Restaurant Operations

- •Making a Profit in Food Service Operations

- •Life in the Restaurant Business

- •Summary

- •Chain Restaurant Systems

- •Independent Restaurants

- •Franchised Restaurants

- •Summary

- •Competitive Conditions in Food Service

- •The Marketing Mix

- •Competition with Other Industries

- •Summary

- •Self-Operated Facilities

- •Managed-Services Companies

- •Business and Industry Food Service

- •College and University Food Service

- •Health Care Food Service

- •School and Community Food Service

- •Other Segments

- •Vending

- •Summary

- •Consumer Concerns

- •Food Service and the Environment

- •Technology

- •Summary

- •The Evolution of Lodging

- •Classifications of Hotel Properties

- •Types of Travelers

- •Anticipating Guest Needs in Providing Hospitality Service

- •Service, Service, Service

- •Summary

- •Major Functional Departments

- •The Rooms Side of the House

- •Hotel Food and Beverage Operations

- •Staff and Support Departments

- •Income and Expense Patterns and Control

- •Entry Ports and Careers

- •Summary

- •The Economics of the Hotel Business

- •Dimensions of the Hotel Investment Decision

- •Summary

- •The Conditions of Competition

- •The Marketing Mix in Lodging

- •Product in a Segmented Market

- •Price and Pricing Tactics

- •Place—and Places

- •Promotion: Marketing Communication

- •Summary

- •The Importance of Tourism

- •Travel Trends

- •The Economic Significance of Tourism

- •The United States as an International Tourist Attraction

- •Businesses Serving the Traveler

- •Noneconomic Effects of Tourism

- •Summary

- •Motives and Destinations

- •Mass-Market Tourism

- •Planned Play Environments

- •Casinos and Gaming

- •Urban Entertainment Centers

- •Temporary Attractions: Fairs and Festivals

- •Natural Environments

- •On a Lighter Note. . .

- •Summary

- •Management and Supervision

- •The Economizing Society

- •The Managerial Revolution

- •Management: A Dynamic Force in a Changing Industry

- •What Is Management?

- •Summary

- •Why Study Planning?

- •Planning in Organizations

- •Goal Setting

- •Planning in Operations

- •The Individual Worker as Planner

- •Long-Range Planning Tools

- •Summary

- •Authority: The Cement of Organizations

- •Departmentalization

- •Line and Staff

- •Issues in Organizing

- •Summary

- •Issues in Human-Resources Management

- •Fitting People to Jobs

- •Recruiting

- •Selection and Employment

- •Training

- •Retaining Employees

- •Staff Planning

- •Summary

- •The Importance of Control

- •Control and the “Cybernetic Loop”

- •Tools for Control

- •Summary

- •Leadership as Viewed by Social Scientists

- •Why People Follow

- •Leadership Theories

- •Communication

- •The Elements of Leading and Directing

- •Developing Your Own Leadership Style

- •Summary

- •A Study of Service

- •Rendering Personal Service

- •Managing the Service Transaction

- •How Companies Organize for Service

- •Summary

- •INDEX

48 |

Chapter 2 Forces Affecting Growth and Change in the Hospitality Industry |

|

|

5.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Meals |

|

4.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commercially Prepared |

per Week |

3.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

1.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

0.0 |

$15,000 |

$25,000 |

$35,000 |

$45,000 |

$60,000 |

$75,000 |

|

|

less |

||||||

|

|

than |

to |

to |

to |

to |

to |

or more |

|

|

$15,000 |

$24,999 |

$34,999 |

$44,999 |

$59,999 |

$70,000 |

|

Annual Household Income

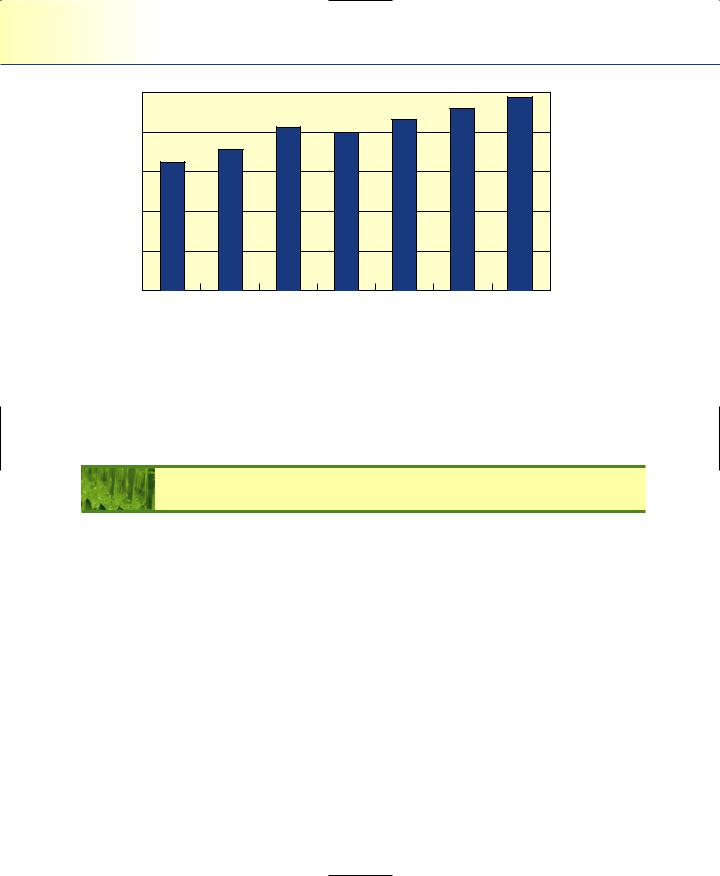

Figure 2.2

Higher income equals more dining-out occasions, 2000. (Source: Meal Consumption Behavior, National Restaurant Association.)

Supply

The key factors of supply that concern us are land and its produce, food, and labor. Capital is a third factor of production, but we will reserve discussion of it until the lodging chapters. The patterns of access to public markets discussed there can,

however, be applied to the hospitality industry in general.

LAND AND ITS PRODUCE

Land and the things that come from the land are classically one of the major factors of production in economics. In hospitality, we are concerned with land itself, as well as with a major product of the land, food.

Land. Because hospitality firms need land for their locations, certain kinds of land are critical to the industry. Good locations, such as high-traffic areas, locations near major destinations, or locations associated with scenic beauty, fall into this category.13 Furthermore, they are becoming scarcer with every passing day for at least two reasons: the existence of established operations and environmental pressures.

INDUSTRY PRACTICE NOTE 2.3

Is the Middle Class Shrinking?

Most North Americans think of themselves as middle class, whatever their actual income is. In the short term, people’s incomes are growing and will continue to grow. After years of salary stagnation in the early 1990s, the typical U.S. household’s income rose by 3.5 percent to $38,885 in 1998. Over a longer time period, from 1990 to 1998, the average household’s income increased 4.1 percent. These averages, however, conceal certain trends. In 1998, the average income of the poorest fifth increased by only 2.4 percent, about the same amount that the top fifth increased. These changes are not as drastic as they have been in previous years, where increases in the upper quintile were much higher.

Defining Middle Class

American Demographics (www.demographics.com/Publications/AD) proposes three definitions of middle class: (1) those with incomes ranging around the national average ($25,000 to $50,000), (2) a broader group with incomes of $15,000 to $75,000, and (3) households with incomes between 75 percent and 125 percent of the median. Although the numbers that emerge from these three categories differ, they all point to a similar conclusion: The proportion of the population that is middle class is decreasing, but with a growing total population, the absolute number of middle-class households is increasing.

The following table shows changes in the number of U.S. households with incomes in the middle range of $25,000 to $75,000 throughout the last three decades. The size of the middle class, in relative terms, decreased from the 1970s into the 1980s but has since shown moderate decreases. The real dynamics seem to be in the two far right-hand columns. Here, we see the number of households increasing significantly during the same period and the proportion tripling. This suggests a growing number of people are stretching the definition of “middle class” by becoming wealthier. To balance that view, however, it is worth remembering that the number in the lower-income category (far left-hand column) increased by 8.1 million people just since 1994,

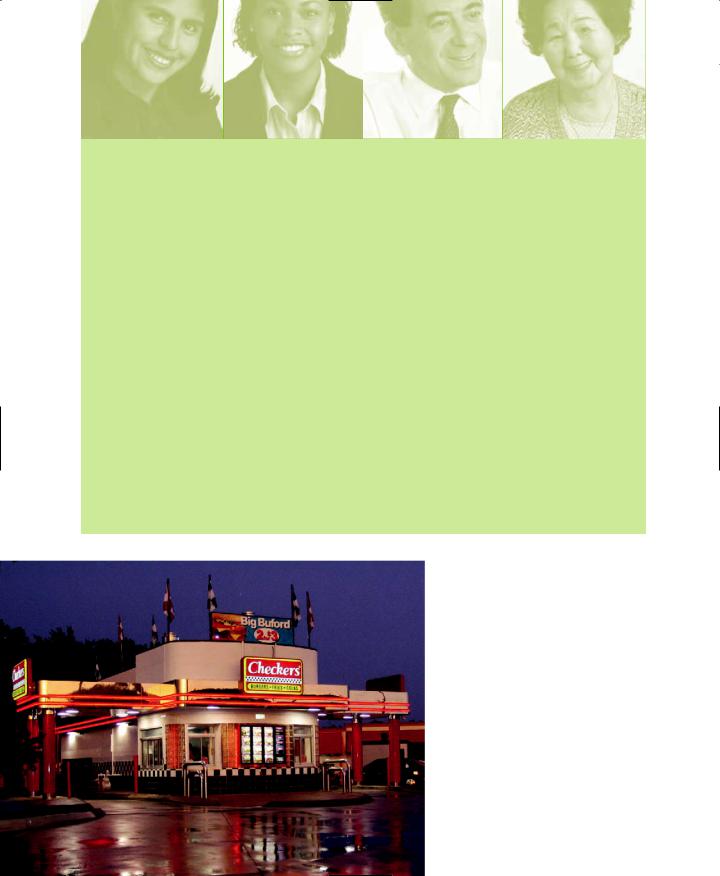

To deal with the first of these, the simple fact is that most of the best high-traffic locations are already occupied. What creates good locations are changes in the transportation system and changes in population concentrations. The building of new highways has slowed greatly compared to the time when the interstate highway system was under construction. As a result, fewer new locations are being created in this way.

In recent years, we have seen restaurant chains acquired by other restaurant chains principally in order to obtain their locations for expansion. One of the factors that led QSR chains to seek locations in malls some years ago was the very shortage of freestanding locations we are discussing.

A second reason for the growing scarcity of locations is environmental pressure. Location scarcity is especially severe in locations such as seashores or wetlands, which are often zoned to prevent building—especially commercial building—in scenic or environmentally sensitive locations. Environmental pressures do, however, go beyond scenic locations. Restaurants, particularly QSRs, are meeting more resistance because of the

49

while at the same time the proportion has decreased somewhat. Finally, the poverty rate in the United States did decline somewhat between 1997 and 1998, from 13.3 percent of the population to 12.7 percent.

The Middle Class is Changing1

|

|

LESS THAN $25,000 |

$25,000 TO $74,999 |

$75,000 OR MORE |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NO. |

|

NO. |

|

NO. |

|

|

INCOME YEAR |

(000,000) |

% |

(000,000) |

% |

(000,000) |

% |

1980 |

32.5 |

39.4 |

42.1 |

51.1 |

7.8 |

9.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1985 |

34.4 |

38.9 |

43.9 |

49.6 |

10.2 |

11.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1990 |

35.3 |

37.4 |

46.5 |

49.3 |

12.5 |

13.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1992 |

37.2 |

35.9 |

50.3 |

48.5 |

16.3 |

15.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1994 |

39.0 |

39.4 |

46.5 |

47.0 |

13.5 |

13.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1996 |

35.0 |

34.6 |

48.2 |

47.7 |

17.9 |

17.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1998 |

33.4 |

32.1 |

49.7 |

47.8 |

20.9 |

20.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2000 |

31.3 |

29.4 |

49.9 |

46.9 |

25.3 |

23.8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2001 |

31.5 |

28.8 |

50.3 |

46.0 |

27.7 |

25.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2002 |

32.6 |

29.3 |

50.9 |

45.7 |

27.9 |

25.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. Household income in constant 2000 dollars.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, “Money Income in the United States,” 2003.

As land and resources become scarcer, companies such as Checkers are making greater use of the space available. (Courtesy of Checkers Drive-In Restaurants, Inc.)

Supply 51

noise, traffic, odor, roadside litter, and crowding that can accompany such operations. Restaurants have been “zoned out” of many communities or parts of communities.

On balance, the greater pressure comes from the impact of present locations being occupied, but, for both reasons discussed previously, land in the form of good locations is a scarce commodity.

Food. Although the cost of food may vary from season to season, for the most part these variations affect all food service competitors in roughly the same way. Food service price changes would have to reflect any change in raw food cost. Food supply conditions do not suggest any major price changes in North America in the foreseeable future, although weather conditions or temporary shortages of certain foods can always drive up some prices in the short term. We should note, however, that major climatic changes, such as those that could be brought on by the greenhouse effect and the Earth’s warming, do pose a longer-term threat to world food supplies.

LABOR

CAREERS IN HOSPITALITYQ

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has developed a long-term forecast of the demand for labor extending over a ten-year period.14 For the years 2000 through 2010, the forecast predicts a growth in the U.S. workforce of 15.2 percent overall. This represents a slight decrease (down from 17.1 percent) from the previous ten-year forecast (1990 to 2000). The same study predicts that the greatest growth will be in jobs requiring advanced education, which bodes well for new college and university graduates. Management jobs, across occupations, will grow by 12 percent over the period, a little less than the overall growth. People interested in careers in food service management, though, can take encouragement from the fact that demand for managers is expected to be about equal to the average for all occupations through 2014 (growth is expected to range from 9 percent to 17 percent). The BLS predicts that new management positions in lodging will grow by the same amount; new chef and head cook positions will increase within the same range as well.

Employment prospects appear to be about average (or a little less) for some of the primary hospitality management occupations. What makes that outlook somewhat more difficult, however, is the relatively high turnover in the industry, highlighted in Table 2.2. High turnover magnifies the demand for labor because it takes a relatively larger number of people to keep positions filled, as indicated in Table 2.3.

Cooking and food preparation jobs will increase—again, a little less than the overall average—by 12.3 percent. Food and beverage server positions, on the other hand, will grow by over 20 percent (22.7 percent). Gaming service workers represent another growth area.15

It is more difficult for us to make projections for the lodging workforce, because in the BLS categories, lodging workers are often merged into other, larger categories—as,

52 |

Chapter 2 Forces Affecting Growth and Change in the Hospitality Industry |

TABLE 2.2

TABLE 2.2

Employee Turnover in Food Service

RESTAURANT TYPE |

ALL EMPLOYEES |

SALARIED EMPLOYEES |

HOURLY EMPLOYEES |

Full service |

|

|

|

Average check under $15 |

64% |

33% |

67% |

Full service |

|

|

|

Average check $15 to $24.99 |

56% |

33% |

60% |

Limited service |

|

|

|

Fast food |

73% |

50% |

82% |

Source: National Restaurant Association, “Restaurant Industry Operations Report,” 2004.

for instance, with “baggage porters and bellhops,” where bell staff are considered along with a number of other, somewhat similar jobs in transportation. Similarly, people working in housekeeping are included in the category of “janitors and cleaners, including maids and housekeeping cleaners.”16

Two categories related to the travel industry are travel agents, slated to grow 3.2 percent (a direct result of changes taking place in the travel industry), and flight attendants, a group projected to increase by 18.4 percent.17

The growth that is expected to occur in these various segments of the hospitality industry means that there will be continued opportunities for hospitality graduates. However, this takes on a different meaning when one adopts a management perspective. Wherever you observe a growth figure higher than the average of 15 percent for

|

|

the workforce as a whole, you may won- |

|

TABLE 2.3 |

der how the industry will go about at- |

||

Top Seven Reasons for Industry Exit |

tracting more than its proportionate |

||

by Former Food Service Employees |

share of workforce growth to that cate- |

||

1 |

More money |

gory of worker. Of course, it is the man- |

|

agers who will have the job of finding |

|||

2 |

Better work schedule |

||

people to fill these fast-growing needs. |

|||

3 |

More enjoyable work |

||

This is of particular concern during pe- |

|||

4 |

Pursue current occupation |

||

riods of low unemployment. Moreover, |

|||

5 |

Advancement opportunity |

||

competitive industries, such as retailing |

|||

6 |

Better employee benefits |

||

and health care, are growing right along |

|||

7 |

To go to school |

||

with the hospitality industry. For in- |

|||

|

|

||

Source: Restaurants and Institutions, May 1, 1997, p. 108, |

stance, retail sales positions will continue |

||

based on the Industry of Choice study of the NRA Edu- |

to grow at about the same rate as the to- |

||

cational Foundation. |

|||

tal workforce, and health care support |

|||

|

|

||