- •CONTENTS

- •PREFACE

- •Content—Benefits for Students

- •Content—Benefits for Instructors

- •Features of the Book for Students and Instructors

- •Supplementary Materials

- •Acknowledgments

- •What Is Hospitality Management?

- •The Manager’s Role in the Hospitality Industry

- •Why Study in a Hospitality Management Program?

- •Planning a Career

- •Employment as an Important Part of Your Education

- •Getting a Job

- •Employment at Graduation

- •The Outlook for Hospitality

- •Summary

- •Managing Change

- •Demand

- •Supply

- •Workforce Diversity

- •The Impact of Labor Scarcity

- •Summary

- •The Varied Field of Food Service

- •The Restaurant Business

- •The Dining Market and the Eating Market

- •Contemporary Popular-Priced Restaurants

- •Restaurants as Part of a Larger Business

- •Summary

- •Restaurant Operations

- •Making a Profit in Food Service Operations

- •Life in the Restaurant Business

- •Summary

- •Chain Restaurant Systems

- •Independent Restaurants

- •Franchised Restaurants

- •Summary

- •Competitive Conditions in Food Service

- •The Marketing Mix

- •Competition with Other Industries

- •Summary

- •Self-Operated Facilities

- •Managed-Services Companies

- •Business and Industry Food Service

- •College and University Food Service

- •Health Care Food Service

- •School and Community Food Service

- •Other Segments

- •Vending

- •Summary

- •Consumer Concerns

- •Food Service and the Environment

- •Technology

- •Summary

- •The Evolution of Lodging

- •Classifications of Hotel Properties

- •Types of Travelers

- •Anticipating Guest Needs in Providing Hospitality Service

- •Service, Service, Service

- •Summary

- •Major Functional Departments

- •The Rooms Side of the House

- •Hotel Food and Beverage Operations

- •Staff and Support Departments

- •Income and Expense Patterns and Control

- •Entry Ports and Careers

- •Summary

- •The Economics of the Hotel Business

- •Dimensions of the Hotel Investment Decision

- •Summary

- •The Conditions of Competition

- •The Marketing Mix in Lodging

- •Product in a Segmented Market

- •Price and Pricing Tactics

- •Place—and Places

- •Promotion: Marketing Communication

- •Summary

- •The Importance of Tourism

- •Travel Trends

- •The Economic Significance of Tourism

- •The United States as an International Tourist Attraction

- •Businesses Serving the Traveler

- •Noneconomic Effects of Tourism

- •Summary

- •Motives and Destinations

- •Mass-Market Tourism

- •Planned Play Environments

- •Casinos and Gaming

- •Urban Entertainment Centers

- •Temporary Attractions: Fairs and Festivals

- •Natural Environments

- •On a Lighter Note. . .

- •Summary

- •Management and Supervision

- •The Economizing Society

- •The Managerial Revolution

- •Management: A Dynamic Force in a Changing Industry

- •What Is Management?

- •Summary

- •Why Study Planning?

- •Planning in Organizations

- •Goal Setting

- •Planning in Operations

- •The Individual Worker as Planner

- •Long-Range Planning Tools

- •Summary

- •Authority: The Cement of Organizations

- •Departmentalization

- •Line and Staff

- •Issues in Organizing

- •Summary

- •Issues in Human-Resources Management

- •Fitting People to Jobs

- •Recruiting

- •Selection and Employment

- •Training

- •Retaining Employees

- •Staff Planning

- •Summary

- •The Importance of Control

- •Control and the “Cybernetic Loop”

- •Tools for Control

- •Summary

- •Leadership as Viewed by Social Scientists

- •Why People Follow

- •Leadership Theories

- •Communication

- •The Elements of Leading and Directing

- •Developing Your Own Leadership Style

- •Summary

- •A Study of Service

- •Rendering Personal Service

- •Managing the Service Transaction

- •How Companies Organize for Service

- •Summary

- •INDEX

128 |

Chapter 5 Restaurant Industry Organization |

2.Identify the independent’s imperative for success; provide an example of this imperative; and identify the independent’s unique market advantage.

3.Explain the difference between product franchising and business format franchising, and identify which is most commonly used in the hospitality industry.

4.List the services the franchisor offers the new franchisee and those offered the established franchisee.

5.List the advantages and disadvantages of franchising to both the franchisor and the franchisee.

Chain Restaurant Systems

Chains are playing a growing role in food service in North America and elsewhere in the world. Moreover, they are prominent among the pool of companies that recruit graduates of hospitality programs and culinary programs. Both factors make them

of interest to us.

Chains have strengths in seven different areas: (1) marketing and brand recognition, (2) site selection expertise, (3) access to capital, (4) purchasing economies, (5) centrally administered control and information systems, (6) new product development, and (7) human-resource development. All of these strengths represent economies of scale: The savings come, in one way or another, from spreading a centralized activity over a large number of units so that each absorbs only a small portion of the cost but all have the benefit of specialized expertise or buying power when they need it.

MARKETING AND BRAND RECOGNITION

More young children in America recognize Santa Claus than any other public figure. Ronald McDonald comes second. Because McDonald’s and its franchisees spend well over $2 billion on marketing and advertising, it’s no wonder more children recognize Ronald than, say, Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, or the Easter Bunny. Indeed, McDonald’s has created a generic item—the Big Mac. The company has done for the hamburger what Coke did for cola, Avon for cosmetics, and Kodak for film. The reasons for this success are threefold: simplicity of message, enormous spending on marketing, and the additive effect. Ideally, for a company, the spending results in brand recognition.

The message of modern advertising is affected by the form in which it is offered: 10-, 30-, or 60-second television commercials, for instance. Even in the print media, the

Many chains are synonymous with well-known brand names. (Courtesy of Darden Restaurants.)

message must be kept simple, because an advertisement in a newspaper or magazine has to compete with other ads and news or feature stories for the consumer’s casual attention. The message of the specialty restaurant resembles its menu. It boils down to a simple statement or a catchphrase. In fact, marketing people generally try to design a “tag line” that summarizes the benefits they want an advertising campaign to tell the consumer. Some years ago, Wendy’s used the slogan “Ain’t no reason to go anyplace else.” Although this slogan set off a letter-writing campaign complaining about the grammar (apparently organized by high-school English teachers), Wendy’s officials judged it effective in “breaking through the clutter.” Of the many other advertising messages that assail the consumer, you will remember classic tag lines of the past that are still revived from time to time:

“We do it all for you.”

“You deserve a break today.”

“Finger lickin’ good.”

129

A standard exterior appearance gives franchise operators and companyowned brands a high recognition value. (Courtesy of Carlson Restaurants Worldwide.)

And, more recently:

“It’s that good.”

“Pizza, Pizza.”

“Burger King, you got it.”

Television advertising, even at the local level, is very expensive. To advertise regularly on national or even regional television is so expensive that it is limited to the very largest companies. Chains can pool the advertising dollars of their many units to make television affordable. Few independents, however, can afford to use television.

Independent restaurants, generally, spend less than chains on marketing as a percentage of sales (of all kinds, including television advertising). Chains have a need to establish and maintain a brand name in multiple markets and to maintain a presence in the regional and national media. Further, restaurants that generate a higher level of sales tend to spend a higher percentage of their revenues on marketing. Table 5.1 reflects spending on marketing, expressed as a percentage of sales, and categorized by check average. In Table 5.1, it is noticeable that the median level of marketing spending for restaurants with check averages of $15 to $24.99 is greater than other categories. Also, full-service restaurants spend more than limited service restaurants. This can be explained by economies of scale. Quick-service company-owned and franchised chain units are fairly close to one another in spending on marketing.1

130

Chain Restaurant Systems |

131 |

TABLE 5.1 |

|

|

|

Marketing Expenditures in Food Service |

|

|

|

LEVEL OF MARKETING EXPENSEa |

|

|

|

|

LOWER |

|

UPPER |

|

QUARTILE |

MEDIAN (%) |

QUARTILE |

RESTAURANT TYPE |

(%) |

|

(%) |

Full service—check average under $15 |

|

|

|

Under $500,000 in annual sales |

0.6 |

1.1 |

2.3 |

Between $500,000 and $999,000 |

0.8 |

1.8 |

3.6 |

Between $1,000,000 and $1,999,000 |

1.2 |

2.4 |

4.1 |

$2,000,000 and over |

0.9 |

2.4 |

3.3 |

Table service—check average $15 to $24.99 |

|

|

|

Under $500,000 in annual sales |

0.9 |

1.5 |

3.3 |

Between $500,000 and $999,000 |

1.0 |

1.7 |

2.4 |

Between $1,000,000 and $1,999,000 |

0.7 |

1.8 |

2.6 |

$2,000,000 and over |

1.2 |

1.9 |

3.0 |

Limited service restaurants |

|

|

|

Under $500,000 in annual sales |

1.0 |

1.4 |

3.4 |

Between $500,000 and $999,000 |

0.6 |

1.1 |

3.7 |

Between $1,000,000 and $1,999,000 |

0.6 |

1.7 |

4.0 |

$2,000,000 and over |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

aRatio to total sales.

Source: National Restaurant Association, “Restaurant Industry Operations Report—2004.”

All this advertising will be effective only if consumers get exactly what they expect. Therefore, chains also concentrate on ensuring consistency of quality and service in operations. Customers know what to expect in each of the units, and in an increasingly mobile society, that is important. For those on the go such as tourists, shoppers, or businesspeople, what is more natural than to stop at a familiar sign? If that experience is pleasant, it will reinforce the desire to return to that sign in the local market or wherever else it might appear.

SITE SELECTION EXPERTISE

The success of most restaurants is also enhanced by a location near the heart of major traffic patterns. The technique for analyzing location potential requires a special

132Chapter 5 Restaurant Industry Organization

kind of knowledge, and chains can afford to staff real-estate departments with people that possess this expertise. Numerous examples abound about independent restaurants not “doing their homework” when choosing a site. While there is no exact formula that will guarantee the absolute best site, and success, chains have both experience and expertise backing them. Site selection, most experts would agree, is only getting more complex, and successful companies are becoming more sophisticated in their approach to it. To quote one industry observer: “Restaurant site selection is increasingly complicated business these days. Demographic studies, focus groups, consumer surveys, consultants and endless number crunching are all part of the formula. No restaurateur—single shingle, multiconcept operator, or large chain—can afford to open an eatery today without spending time and money on some or all of the above.”2

Sophisticated software is now available to assist operators in their decision making. Papa John’s, Krispy Kreme, AFC, and of course, McDonald’s are all companies that are recognized for doing an admirable job of site selection.

ACCESS TO CAPITAL

Most bankers and other lenders have traditionally treated restaurants as risky businesses, therefore making access to capital (at least from this source) problematic. Because of this, an independent operator who wants to open a restaurant (or even remodel or expand an existing operation) may find it difficult to raise the needed capital. However, the banker’s willingness to lend increases with the size of the company: If one unit should falter, the banker knows that the company will want to protect its credit record. To do so, it can divert funds from successful operations to carry one in trouble until the problems can be worked out. Although franchisees are not likely to be supported financially by the franchisor, franchise companies regard a failure of one unit as a threat to the reputation of their whole franchise system and often buy up failing units rather than let them go under. In any case, failure is much less common among franchised restaurants than among independent operations. Not surprisingly, banks not only make capital available to units of larger companies and to franchised units but also offer lower interest rates on these loans.

Publicly traded companies, whose stocks are bought and sold on markets such as the New York Stock Exchange, can tap capital from sources such as individual investors buying for their own account, as well as mutual funds, insurance companies, and pension funds that invest people’s savings for them. Hospitality companies with well-known brand names and well-established operating track records enjoy a wide following among investors, and their activity is important enough to the

Chain Restaurant Systems |

133 |

industry that Nation’s Restaurant News carries a weekly section, “Finance,” featuring a summary of approximately 100 publicly traded restaurant stocks. In addition to funds raised through stock sales, companies can sell bonds through public markets, raising larger sums than are typically available through bank loans. Among others, Norman Brinker (Jack-in-the-Box, Steak n’ Ale, and Chili’s) developed a reputation for successfully taking his restaurant companies public and thus achieving his growth objectives.3

It should be noted here that the evidence suggests restaurant failure rates tend to be greatly exaggerated. Without publishing the commonly touted failure rates, we can say that recent research indicates that the failure rate is relatively similar to other types of businesses—somewhat lower than 60 percent over a three-year period according to one study.4

PURCHASING ECONOMIES

Chains can centralize their purchasing, thereby creating purchasing economies. This is accomplished either by buying centrally in their own commissary or by negotiating centrally with suppliers who then deliver the products, made according to rigid specifications, from their own warehouses and processing plants. Chains purchase in great quantity, and they can use this bargaining leverage to negotiate the best possible prices and terms. Indeed, the leverage of a large purchaser goes beyond price. McDonald’s, for instance, has persuaded competing suppliers to work together on the development of new technology or to share their proprietary technology to benefit McDonald’s. In addition, chains can afford their own research and development laboratories for testing products and developing new equipment.

CONTROL AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS

Economies of scale are important when it comes to control and information systems as well. Chains can spend large sums on developing procedures for collecting and analyzing accounting and marketing information. They can devise costly computer programs and purchase or lease expensive computer equipment, again spreading the cost over a large number of operations. Daily reports often go from the unit’s computerized point-of-sale (POS) system to the central-office computer. There they are analyzed, problems are highlighted, and reports are sent to area supervisors as well as to the unit. This means follow-up on operating results can be handled quickly. Moreover, centrally managed inspection and quality control staff review units’ efficiency and quality regularly.

134 |

Chapter 5 Restaurant Industry Organization |

NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

The quest to create newer, better, and more interesting food products continues as competition in the restaurant industry only intensifies. Chains have the luxury of being able to staff (and finance) research and development departments that champion the development of new menu items. With adequate financial support and expertise, companies are able to test and launch new products such as McDonald’s new Toasted Deli Sandwiches, Burger King’s Chicken Fries and Chicken Whopper, or Papa John’s Cheesesticker. The development of new products for restaurant companies is a combination of culinary expertise and food science expertise. Many of the chefs that head culinary development departments for restaurants are enthusiastic members of the Research Chefs Association. The association currently has over 1,000 members and is devoted to “providing the

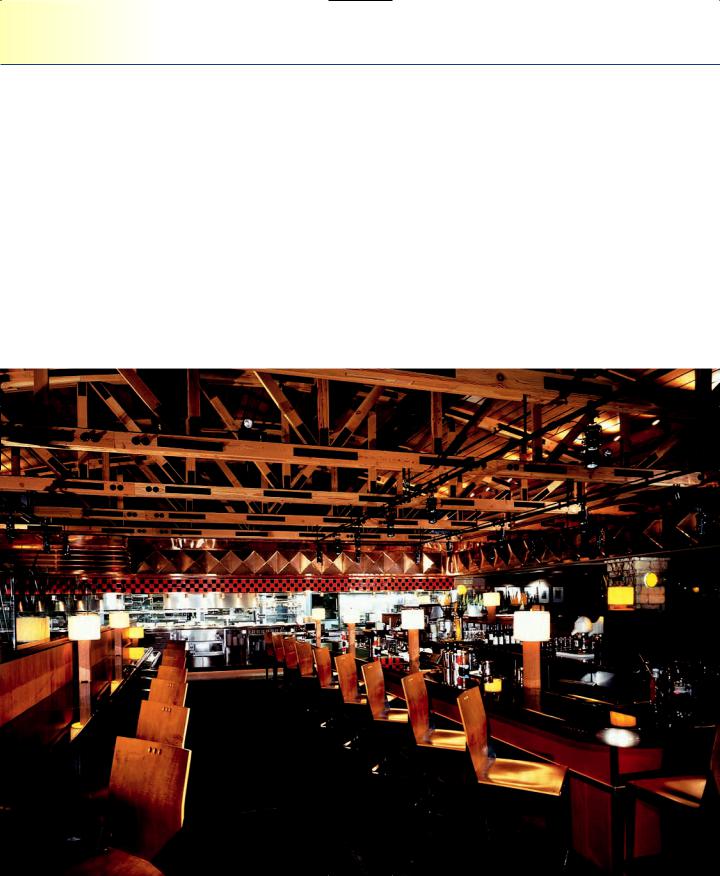

Houston’s Restaurants, a privately owned company, is well known for its development programs. (Courtesy of Houston’s Restaurants.)

Chain Restaurant Systems |

135 |

research chef with a forum for professional and educational development.” Many chain organizations have membership in the association including such companies such as Starbucks and Brinker International. The ability to add new products to the menu mix is an important quality; new products can create positive press, increases in sales and profits, and increased market share.

HUMAN-RESOURCE PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT

Some restaurant chains have established sophisticated training programs for hourly employees, using computer-based, and increasingly, Internet-based techniques to demonstrate the proper ways of performing food service tasks and jobs. Special training exercises are also now available to subscribing companies through closed-circuit television. The standardized procedures emphasized in company training programs, in turn, lower the cost of training and improve its effectiveness. This saving is especially advantageous in semiskilled and unskilled jobs, which traditionally experience high turnover rates and, therefore, consume considerable training time. Companies that are leading the way in computer-based training include Captain D’s, Sonic, and Damon’s Grill. According to a report on training by Restaurants & Institutions, Damon’s Grill employees can access the company’s computerized training program through their POS system.5

Management training is also important, and large food service organizations can usually afford the cost of thorough entry-level management training programs. One food service company, for instance, estimates the costs for training a management trainee fresh out of college to be about $20,000 over a 12to 18-month period. This includes the trainee’s salary while in training, fringe benefits, travel and classroom costs, and the cost of the manager’s time to provide on-the-job training. In effect, this company spends as much as or more than a year of college costs on its trainees, a truly valuable education for the person who receives it.

Because of their multiple operations, moreover, chains can instill in beginning managers an incentive to work hard by offering transfers, which involve gradual increases in responsibility and compensation. In addition, a district and regional management organization monitors each manager’s progress. Early in a manager’s career, he or she begins to receive performance bonuses tied to the unit’s operating results. These bonuses and the success they represent are powerful motivators.

CHAINS’ MARKET SHARE

As Figure 5.1 suggests, chains have dramatically increased their market share (share of sales) over the last three decades. The top chains generate over half the restaurant