- •NEWS IN BRIEF

- •TEXTS FOR READING

- •The Russian Avant-Garde Animated

- •METHODS OF TEACHING

- •A Continuous Teacher

- •PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

- •FOCUS ON LANGUAGE

- •Падеж существительных

- •Time Is Running Out!

- •Where Cognitive and Corpus Linguistics Meet

- •FOR YOUNG LEARNERS

- •The Time to Rhyme

- •SCHOOL THEATRE

- •How the Grinch Stole Christmas

- •Five-Minute Tests

- •LESSON PLANS

- •Interview with Paul De Quincey

- •Exhibitions

- •Music

- •YOUTH ENGLISH SECTION

- •GOOD NEWS

- •INFORMATION

- •2014 in Review

English |

|

YOUTH ENGLISH SECTION |

|

|

38 |

|

|

|

|

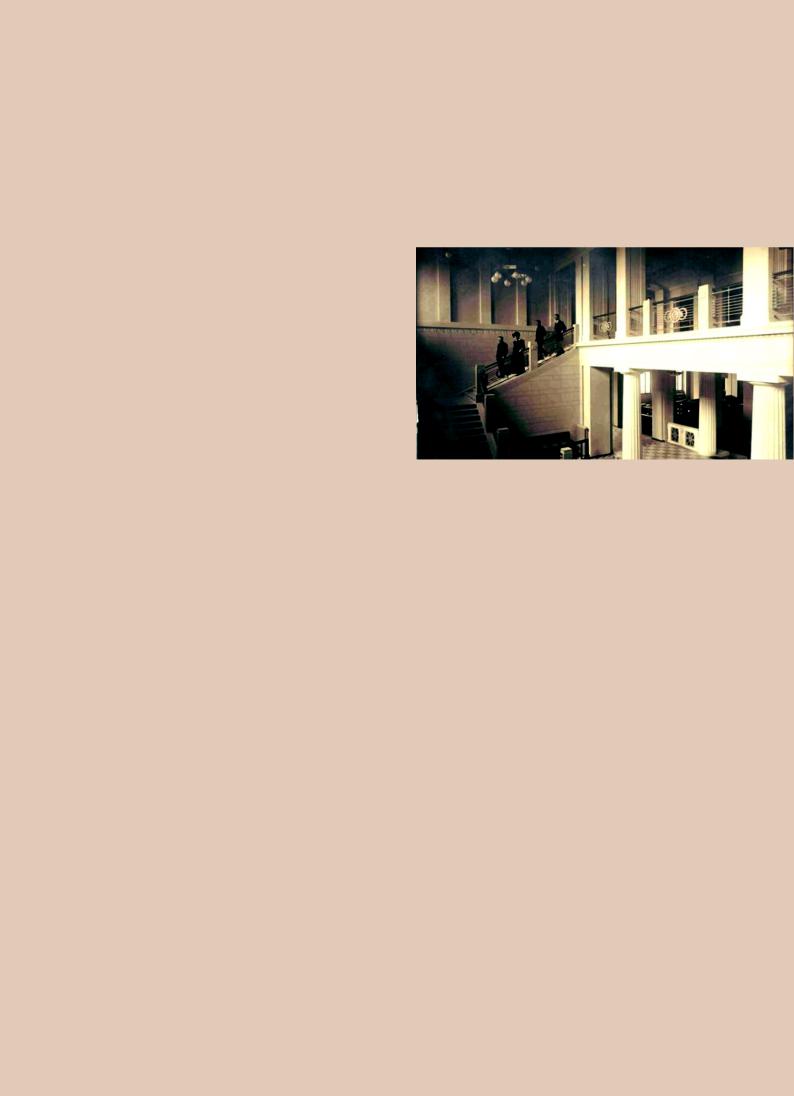

SHEFFIELD DOC/FEST |

||||

December 2014 |

||||

CAME TO MOSCOW

As part of the UK–Russia Year of Culture, the famous documentary film festival Sheffield Doc/Fest showcased five works in Moscow.

Sheffield International Documentary Festival or Sheffield Doc/Fest is a distinguished and significant event in the UK. It is held in Sheffield every year. It is famous for not only its screenings, but its industry events also (pitches, public talks, debates, etc.).

In Moscow, it also included a showcase of documentary films and public talks with teams of experts. The festival presented five winners from the last five years.

Here are some words about the three films I liked most (though all of them are obviously great).

The Big Melt is a film based on footage found in the British Film Institute archive. It is about the Sheffield steel industry and it covers over one hundred years. The film was created by Martin Wallace and Jarvis Cocker. It was made with music performed by many famous musicians, including musicians from Sheffield. The film has no narrative or leading actors. It is a mixture of short pieces from the BFI archive. All of the pieces have a common idea, and all of them tell the audience the history of steel in Sheffield. The picture is dynamic and gripping, it is also very easy to understand. The Big Melt is strongly recommended for all who love to look at earlier times.

The Great Hip Hop Hoax is a picture about two men who cheated the world. Two prospective musicians want to form a duo. They, however, have one big problem preventing them being famous – they are Scottish, and Scottish rap is something others do not want to take seriously. They are talented, but they are powerless to succeed. Realising that, Gavin Bain and Billy Boyd decided to lie about their origins. It is for the best, they think, and now they are two Americans from California. How long it will take the world to learn the truth is just a matter of time. In the astonishing documentary

about the global deception and how it comes to an end, film director Jeanie Finlay let the spectators feel the atmosphere of the success of Silibil N’ Brains’ and their fear of being exposed.

Project Wild Thing is a light and a very kind picture about a man who tries to make the world better. David

Bond wants his children to lose of their dependency on TV, and get them back to nature. The desire to make the children less ‘city kids’ turns out to be to a major campaign throughout the entire UK. How it began, and how it develops – this is the story of how one intention can change the world.

In summary, it also should be noted that documentary films are not as popular in Russia as action films. Documentary is an unappreciated genre here in our time. There are very few places where spectators can see documentary films. Nevertheless, there have been many special events and festivals of documentary films lately. Sheffield Doc/Fest is a major step toward an increasing interest in documentary films in Russia. And as the auditorium was crowded, it might be supposed that the situation is going to improve soon.

Christina Loginova,

Moscow State University, Faculty of Journalism

|

FOCUS ON LANGUAGE |

|

English |

What’s the Future |

39 |

||

December 2014 |

|||

of English? |

|

||

Linguistics expert David Crystal is in Russia to give a series of lectures. At the UK-Russia Linguistic Symposium at the Russian State University for the Humanities in Moscow, he described ‘the future of Englishes’ and the evolution of global varieties of English across the world. Keira Ives-Keeler of the British Council in Russia explains.

Advertising campaigns give an insight into how languages evolve

What role does advertising play in the evolution of languages and the relationship between language and cultural knowledge? Using the example of the well-known Heineken slogan, ‘Heineken refreshes the parts other beers cannot reach’, David Crystal explained how this initial phrase evolved with the help of word play. Over 30 years, the phrase came to represent an ad campaign with 300 variations on the same phrase, with the word ‘parts’ substituted with everything from ‘parrots’ to ‘pilots’ to ‘poets’.

Understanding different cultures helps people understand different languages

David Crystal recounted the difficulties he had in explaining the Heineken campaign’s meaning to a group of Japanese English language teachers when they stumbled across a billboard for it whilst on a study trip to the UK. Their confusion highlighted the importance of cultural understanding as a tool for understanding languages.

He found it equally challenging to convey the same message and humour to an American friend when they came across the same billboard just a week later – demonstrating that even native speakers often require cultural context in order to fully understand phrases in their mother tongue, as culture inevitably shapes the language that we use on a daily basis. As a localised national advertising campaign run exclusively in Britain, only those living in Britain and exposed to the campaign would understand the reference to ‘refreshing the parrots that other beers cannot reach’. The phrase was utterly incomprehensible to anyone outside of that specific context.

New forms of ‘English’ are swiftly evolving

Crystal estimates that around 60-70 new ‘Englishes’ have emerged since the 1960s in countries across the globe. There are an estimated 400 million people who speak English as a first language and 7-800 million people who speak English as a second language. Around a billion more speak English as a foreign language. This means that now there is just one native speaker to every five non-native speakers of English

– an unprecedented situation in the history of languages. It also means that people are no longer exclusively looking to Britain. British English is now a minority amongst the many ‘Englishes’ that are spoken around the world.

‘English is of no use beyond our shores’, stated the Earl of Leicester upon returning from his tour of Europe in the late 1500s. Indeed, Chaucer asked why anyone would want to study English: a language ‘with no literature’ (as David

pointed out, though, anyone lucky enough to have studied Chaucer would be able to confirm that his works are almost unintelligible to modern English speakers). And yet, in the very same year, Shakespeare emerged from his ‘lost years’

– a period from 1585 to 1592, when it was thought that the playwright was perfecting his dramatic skills and collecting sources for plots – and produced some of his finest work. Just over a decade later, Walter Raleigh’s expeditions in the early 1600s saw American English take root within a matter of days, with terms such as ‘wigwam‘ and ‘skunk‘ appearing and becoming commonplace extremely quickly. It takes very little time for a language to evolve; this language ‘of no use beyond British shores’ grew from a population of four million speakers to two billion in just 400 years.

A language’s development reflects the power of those who speak it

So how exactly did that happen? How did English grow so quickly and seemingly so unexpectedly? According to Crystal, in spite of the widespread notion that this is due, at least in part, to the fact that it is an easy language to learn, ‘without any grammar’, as some people have said, there is something much deeper behind the exponential growth of English as a global language. Crystal suggests that a language’s development is a direct reflection of the power of those who speak it. From the beginnings of the British Empire, to the industrial revolution in Britain, which brought significant technological and scientific developments and a number of influential inventions from English-speaking inventors, through to the continued economic power of the 19th century and cultural power of the 20th century, English has maintained its edge.

Speakers of English adapt the language to their local context

Turning his attention to colonial and post-colonial environments, Crystal suggested that even in countries where English was seen as the language of oppressors, complexities in the linguistic make-up of the local environment (for example, Nigeria where 500+ languages are spoken) meant that a ‘better the devil you know’ approach was adopted ‘because at least everyone hates English equally’. This meant that English was adopted as an official language and then adapted to the local context. Within months of independence, thousands of new words appeared, linked to politics, food and drink, folklore and plants. Fifty years on, these words are featured in dictionaries of global English – there are 15,000 Jamaican words and 10,000 South African words alone.

This trend of ‘Englishes’ in the plural shows no sign of slowing down anytime soon. But nothing lasts forever. Who knows whether English will retain its position as the widely accepted lingua franca. And if it does, then how many ‘Englishes’ might evolve? How can we prepare our students and in particular younger generations for this culturally diverse future?

By Keira Ives-Keeler, Assistant Director, British Council Russia

English |

|

FOCUS ON LANGUAGE |

|

40 |

|

ORIGINAL PRONUNCIATION: |

|

December 2014 |

|

||

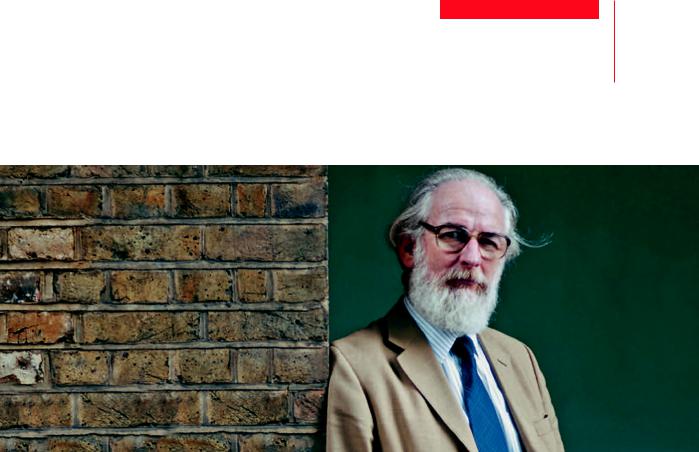

THE STATE OF

In 2004, Shakespeare’s Globe in London began a daring experiment. They decided to mount a production of a Shakespeare play in ‘original pronunciation’ (OP) – a reconstruction of the accents that would have been used on the London stage around the year 1600, part of a period known as Early Modern English. They chose Romeo and Juliet as their first production, but – uncertain about how the unfamiliar accent would be received by the audience

– performances in OP took place for only one weekend. For the remainder of the run, the play was presented in Modern English. The poor actors had to learn the play twice! I’ve told the story in the book Pronouncing Shakespeare (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

The experiment was a resounding success. It turned out that all sorts of people were interested in OP – what it sounds like, how it affects actors’ performance, how historical phonologists reconstruct it (the ‘how do we know?’ question). At the talkback sessions following the performances, alongside British Shakespeareans there were early music enthusiasts, people involved in heritage sites, and visiting theatre buffs from abroad. They all had one thing in common: they wanted to get closer to the speech or song patterns that would have been around in the Jacobethan period. The Romeo performances had convinced them that this was possible, and they wanted a slice of the action. As did the Globe itself, of course. The following year the experiment was repeated. But instead of a tentative toe in the linguistic water, a new production of Troilus and Cressida was entirely devoted to OP.

Ten years on, the UK–Russia year of culture gives an opportunity to reflect on the way events subsequently ‘galloped apace’. In the Shakespeare world, the Globe went in other directions and the initiative moved to the USA. In 2006, OP extracts from Shakespeare were presented during the 400th anniversary of Jamestown celebrations. In 2007 OP readings took place in an offBroadway venue in New York. In 2010, a full-scale OP production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was put on at Kansas University, and this was followed up by a recording for radio and a DVD (now available commercially). In 2011, another university production, this time at the University of Nevada (Reno) mounted an OP production of Hamlet. My actor/director son Ben, who was becoming an expert in OP performance, was invited to be an artist in residence and to play the Dane.

I was the consultant on both these productions, and saw the results. Thanks to solid and sustained periods

of rehearsal by all concerned, the OP was phonetically excellent. It’s absolutely essential to devote time and expertise to ensure that the pronunciation is confidently and consistently produced. There have unfortunately been a few instances of companies jumping on the OP bandwagon, and rushing out a production, but without spending the time needed to develop consistency and to think through the various choices that need to be made (for OP allows several alternative pronunciations, just as English accents do today).

The number of works I know of that have been produced with appropriate attention paid to the OP has grown dramatically over the past three years, and includes the Sonnets, Twelfth Night, As You Like It, and

Julius Caesar. At the same time, the number of resources has increased, so that more people are able to hear what OP sounds like, notably via the British Library CD, Shakespeare’s Original Pronunciation – an anthology of extracts curated by Ben in 2012. Ben’s reading of Sonnet 141 in OP for the best-selling app The Sonnets (2013) made the accent reach a wider audience than ever before. But the recording he and I made on OP at the Globe for the Open University in 2011 has had the widest reach. During the year of culture it went viral, with almost two million hits to date.

In addition to the website created to accompany Pronouncing Shakespeare, there’s now a website dedicated to the whole subject of OP – going well beyond Shakespeare to include anyone exploring accents from any period of the history of English. That’s where you’ll find out about those who are using OP to produce fresh versions of Dowland, Byrd, and Purcell, or projects involving other authors. The addresses are below.

Two of these other authors have had special attention

– one earlier, and one later. I made a CD for the British Library of William Tyndale’s Matthew Gospel, in the OP of the early 16th century – a notable difference is that silent letters in words like know are pronounced, so we get gnashing of teeth with a mouth-watering onset. And Ben adopted the persona of John Donne for a recording of his 5 November 1623 sermon. It was selected by the curators of the Virtual St. Paul’s project – an online recreation of how St. Paul’s would have looked and sounded at the time, with the aim of answering the question how it was possible for 2000 or more people to hear Donne speak in the Cathedral grounds.

With all this going on, the Globe eventually took another bite of the apple, the opportunity being provided

FOCUS ON LANGUAGE English |

41 |

December 2014 |

THE ART IN 2014

by the completion of the new indoor theatre at Shakespeare’s Globe, called the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse (named after the American actor whose vision it was to reconstruct the Globe). In July 2014 the OP story was told in a three-part series of events, using play-extracts, sonnets, and songs, and ending with a full reading of Macbeth by Ben’s Shakespeare Ensemble, the foremost developers of OP practice over the past few years. That has sparked fresh interest, and over the next year a number of OP productions are being planned. For example, in January 2015, the Ensemble will present an OP Pericles in Stockholm, accompanied by the Swedish Radio Orchestra. Expressions of interest in learning OP from individual actors and companies has dramatically increased, so Ben has formed a new Company to coordinate activities and meet the rising demand.

It’s an exciting time. People often say that there’s nothing new to be learned about Shakespeare, given that he has been the subject of study for hundreds of years. Not so, when it comes to OP. Every time I explore a play in this way I discover something new – some previously unnoticed piece of wordplay, for example – or experience a fresh auditory impact from individual lines and interactions. With a play that has lots of rhymes that don’t work in Modern English (such as Dream), suddenly all the rhymes work! Audiences immediately notice the effect. When the Three Witches open Macbeth, they speak in rhyming couplets (as witches – and fairies – always do), but ‘Upon the heath’ doesn’t rhyme with ‘There to meet with Macbeth’ in Modern English. It does in OP. Heath was pronounced with a more open vowel.

An exciting time lies ahead. As of 2014, only a dozen plays have been explored in OP, and few places have yet had the chance to hear it in action. During my talks in Moscow and St. Petersburg there were some opportunities to illustrate it, but small extracts don’t compete with full productions that explore original practices (relating to all aspects of dramaturgy, of course, not just OP). Over the next few years I’m expecting there to be many more occasions for audiences to experience an OP production, so that they can judge for themselves the dramatic and aesthetic impact of presenting a play in a way that is as close as possible to how it would have been performed 400 years ago.

Resources

•http://www.pronouncingshakespeare.com

•http://www.originalpronunciation.com

•Virtual St. Paul’s: http://vpcp.chass.ncsu.edu

•Open University: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gPlpphT7n9s

•Dream DVD: http://ffh.films.com/ItemDetails.aspx?TitleId=30535

•British Library Shakespeare CD: http://shop.bl.uk/mall/productpage.cfm/BritishLibrary/_ISBN_9780712351195

•British Library Tyndale CD: http://shop.bl.uk/mall/productpage.cfm/BritishLibrary/_ISBN_9780712351270

David Crystal

English |

|

FOCUS ON LANGUAGE |

|

42 |

|

“HOW THE CHANGING WOR |

|

December 2014 |

|

||

|

|

|

IS REFLECTED IN EN |

|

|

|

The International |

This bilateral event was held on 9–10 June 2014, as part of the UK-Russia Year of Culture 2014 hosted by the University for the Humanities.

It brought together leading philologists, foreign language teachers and methodologists, translators and other professionals from both countries.

Below you can find some of the most outstanding speeches.

Changes in the Russian World View

under the Influence of the Global Language and Culture

At the end of the 20th century Russia emerged on the world scene like a bewitched princess having been imprisoned for 70 years. That is why Russia is the right place to discuss linguistic and cultural changes. Indeed, after seventy years of complete isolation in an iron cage (sorry, behind the iron curtain), suddenly having entered the “open global world” we were not immune to the treasures and tricks of this world which resulted in our happy and greedy borrowing of everything: styles, ideas, advertisements, mass media, TV programmes, communicative behaviour, ways of life and, first and foremost, words reflecting all these novelties.

The main source for all this has been English as the global language of the global world. The forbidden fruit effect has added to our natural enthusiasm, curiosity and strangely, unbelievably keen interest in everything foreign. Its “strangeness” is determined by the fact that though Russia and Russians are geographically isolated they, unlike other isolated (mostly island) cultures and countries, have not developed a strong dislike for foreignness and foreigners openly and vividly expressed by their languages. Russia is not an island, but its geographic isolation is unique: it represents two parts of the world, Europe and Asia. Thus we represent both cultures: European and Asian or, rather, neither of them because we are Asians for the Europeans and Europeans for the Asians. All this has made Russia and everything Russian an ideal object for discussing how a changing world view is reflected by languages – in this case by Russian under the influence of English.

The contemporary changes in the Russian mentality and way of life have been caused by the avalanche-like “intrusion” of English into the Russian language, culture and life.

The impact of English-American (increasingly – American) culture via the English language can be seen in different spheres, being especially obvious in the field of business.

The very Russian traditional form of address by first name and patronymic is disappearing due to imitation of the western pattern. Indeed, from time immemorial, a patronymic as a middle name “derived from the name of a father or ancestor” (The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary) has been used as an official respectful form of addressing older people (Grigory Ivanovich, Svetlana Grigorievna).

Nowadays it is hardly ever utilised in business Russian, business cards giving only first names and family names. A businessman asked directly, “What is your patronymic?” usually answers “I don’t need it any longer”.

Another cultural borrowing concerning names is the new fashion of giving the initial of a father’s name instead of patronymic (Anna A. Zaliznyak) and of using two or more first names (Anna-Natalia Malakhovskaya; Oleg Roman David Kuznetsov).

Another new feature coming from the field of business: In the Russian tradition of letter-writing it was obligatory that the opening greeting of the addressee be followed by an exclamation mark !. I remember very well how shocked I was many years ago in the Soviet Union when I got my first letter from “a capitalist country” where my first ever American friend wrote to me “Dear Svetlana,” with a comma. I was hurt: “Why? What had I done to be humiliated with a common comma instead of being greeted with a proud exclamation mark?!” I was even more surprised when in her second letter she asked me why I had put an exclamation mark after her name.

|

FOCUS ON LANGUAGE |

|

English |

LD VIEW |

43 |

||

December 2014 |

|||

GLISH AND RUSSIAN” |

|

||

Linguistic Symposium |

|

||

Nowadays, a comma after the name of an addressee is a regular practice in Russian business letters. In ordinary letters young people use more and more often the Internet smiley sign :) instead of our dear old exclamation mark. Thus, the Russian language is becoming less emotional than it used to be, and more business-like and reserved, which may lead to a change in the Russian national character in the not-so- distant future.

In the Russian language the only personal pronoun which is always written with a capital letter is Vy (You), second person, plural, addressed to a single person in order to emphasise special respect and politeness. In English only I, first person, singular is spelt as a capital letter. Thus while the Russian language provides its users with a spelling rule to show extra respect and politeness to other people, the English language uses the same means to indicate self-esteem – which seems to illustrate collectivism of the Russian culture and individualism of the English culture. Nothing has changed yet in this respect but, surprisingly, even shockingly to older generations, young Russians have begun appealing to the public on the Internet that this practice should be changed to the English model. In 2011 on Rutube a new cartoon appeared entitled I as a Capital letter. Mr. Freeman. Interestingly enough, the first part of the title was written in Russian: “Я с большой буквы”. The speaking surname Mr. Freeman was written in English.

The cartoon is a stirring appeal to young people to start spelling Я (I) in Russian as a capital letter. Here are some extracts illustrating the passionate way it is presented.

Children, young people, free yourselves from the tyranny of parents, from the prohibitions of adults. The social system of the past enslaved everybody, therefore all people in Russia were the same, that is, law-abiding. We should not be identical, we must be different!

The first step is to write Я (I) as a capital letter. We must proudly bear our Я like a banner of our individuality and freedom.

This change in spelling appears likely, inevitable even, when the new generation of Russians grows up and comes to power.

One more present-day Russian language and culture novelty which is becoming increasingly widespread under the influence of English is the flood of various kinds of abbreviations which are meant to facilitate communication, but often prevent it.

Just one example. A Russian company exporting timber called by the acronym Экспортлес (Exportles, лес [les] meaning timber and/or wood) used as the English variant of its name Exportless which sounds like no export or so bad it can’t be exported.

In the course of interaction both languages are suffering being violated, deviated and distorted. The global language is often adjusted to the national one.

The Russian inclination to be openly emotional and affectionate, expressed and reflected by the Russian language through a great stock of diminutive affectionate suffixes, may be illustrated by the Russian word смайлик (‘smaili:k) a smile as an Internet icon. In the Russian version a popular and frequently used word smile is decorated with a Russian affectionate suffix ik which seems quite appropriate because smiling is a very nice thing. More examples: badgik (badge), perfumechik, and even freelovechik.

A serious threat to the Russian language and culture comes from the field of translation. The flood of English books, films, magazines, newspapers, TV and radio broadcasts demands immediate translation – the sooner the better, the latter meaning the more profitable, especially in case of books and films. The combination of greedy publishers and film distributors with incompetent and equally greedy translators, who are not controlled or edited by anyone, results in a lot of harm for both languages, but more so for Russian.

This problem is best illustrated by the translations of proper names in literature, bilingual English-Russian dictionaries and encyclopedias. Proper nouns have been chosen as an example of dangerous changes in the Russian language and especially culture because, more than other words, they are loaded with a cultural component.

Indeed, proper nouns – mostly anthroponyms (names of people) and toponyms (geographical names) – compose a significant part of language’s socio-cultural context and the language and culture picture of the world, not least because they are proper, that is, they signify “individual objects without reference to their features” (Olga S. Akhmanova, Dictionary of Linguistic Terms, Moscow, 1996, 2004, p. 175).

Proper nouns are a very important national component of both the language and culture pictures of the world, and for this reason they are a powerful defense weapon for national identity.

English |

FOCUS ON LANGUAGE |

44

December 2014

Accordingly, the translation of proper nouns in bilingual dictionaries requires, strange as it may seem, a great deal of caution, effort, and knowledge of the cultural background in general.

The ‘military’ metaphor comes from the title of my recent book War and Peace of Languages and Cultures discussing the idea that language is not just a barrier separating peoples but also – and more importantly – a shield defending the national identity of ‘its people’, that is, the people using it as a means of communication.

The role of proper names in the language and – especially

– culture picture of the world cannot be overestimated. One little example illustrating how a proper name reveals both the culture picture and the changes it has undergone: The sociocultural position of women in Old Rus becomes clear from the fact that in those days a woman seems to have been nameless as she was addressed by her patronymic and not by first name… In the famous Russian epic The Song of Igor’s Campaign (immortalised by Borodin’s opera Prince Igor) Igor’s wife is called Yaroslavna which is her patronymic, that is, a derivate from Yaroslav, her father’s name. We do not know her first name. Thus, the prince was known as Igor, and his wife as Yaroslav’s daughter.

The careless handling of proper nouns – both anthroponyms, the names of people, and toponyms, which are geographical names – can inflict significant damage on meaning, historical truth, pictures of the world, and communication in general. In other words, the non-recognition or inaccurate rendering of proper nouns can cause setbacks in communication and instead of bringing people closer together, will divide them.

Such examples as Джон Баптист (John the Baptist) instead of Иоанн Креститель (Joann Baptiser) and Мэри дочькороляГенри(Mary, daughter of King Henry) instead of

Мария Кровавая/Мария I, дочь Генриха VIII (Mariya Krovavaya – Bloody Mariya or Mariya I, daughter of Genrykh VIII) in addition to testifying to the ignorance of the translators and authors of dictionaries and encyclopedias, also deform and distort the Russian cultural and linguistic pictures of the world, which is much more serious and dangerous.

The presentation of proper names in bilingual dictionaries implies their translation into some other language. Academician Oleg Nikolaevich Trubachov, the eminent Russian linguist, brilliantly revealed this twofold problem of proper nouns – translational and lexicographical – in his criticism of the Russian edition of Hutchinson’s Pocket Encyclopedia

(Helicon, Oxford, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995).

The Russian version of the above-named Encyclopedia, striking in its incompetence, ignorance, and lack of culture, provides such a large quantity of mistakes, errors, inexactitudes, and absurdities in translation that it can serve as excellent material for academic research on translation under the heading How not to translate, or what poor translation leads to.

In the opinion of academician Trubachov, the translation of this ‘pocket encyclopedia’ “is a glaring example of inadequate

knowledge of everything that it is necessary to know – the English language, history, and culture, and European languages, history, and culture, to say nothing of the total ignorance of that which is perhaps most important for a Russian publication, namely the Russian language picture of the world.”1

We will cite only some examples (to cite all of them is impossible) of the innumerable mistakes in the reproduction of proper nouns – and not just any proper noun, but only the names of people and the geographical place names who left their mark on culture and history, and were participants or witnesses of historical events, that is, those belonging to the highest cultural stratum and granted the honour of being included in an encyclopedia.

The main problem is deviation from and distortion of the traditional way of presenting proper names in another language and, consequently, culture (in this case – Russian) at the level where they are generally unrecognisable. The inaccuracies and mistakes can be roughly classified as follows:

The way proper names bor- |

Their translation in the Rus- |

rowed from other languages |

sian edition of Hutchinson’s |

are traditionally presented |

Pocket Encyclopedia. |

in Russian. |

|

1. By pronunciation |

|

Жорж Сера |

Джордж Сейрат (translitera- |

(Georges Seurat) |

tion; the first name anglicised) |

Энгр (Ingres) |

Ингрес (transliteration) |

Юджин О’Нил |

Евгения О’Нил (The first name |

(Eugene O’Neill) |

is rusified by adding the ending я |

|

– ja which turns Eugene O’Neill |

|

into a woman.) |

Нидерланды |

Лоукантриз (transliteration of |

(the Netherlands) |

pronunciation of low countries), |

|

нижние страны (translation) |

2. By transliteration |

|

Шварцвальд (Schwarzwald) |

Черный лес (translation) |

Брауншвейг (Braunschweig) |

Брюнсвик (unrecognisably dis- |

|

torted pronunciation) |

3. By translation (of words or |

|

parts of a word) |

|

оз. Верхнее (Lake Superior) |

Озеро Cьюпериор (pronuncia- |

Lake the Upper |

tion and transliteration) |

Карл Великий (Charlemagne) |

Карлеман (corrupted pronuncia- |

Karl the Great |

tion of Charlemagne) |

Иоанн Безземельный (John |

Джон Лекленд (pronunciation) |

Lackland) |

|

Joann the Landless |

|

4. By historical tradition |

|

Царица Савская |

Королева Шеба (translation and |

(The Queen of Sheba) |

transliteration) |

Zarina of Sava |

|

Лотарингия (Lorraine) |

Лоррен (pronunciation) |

Lotaringiya |

|

This list can be continued, but the examples cited are enough to understand that such mistakes in proper nouns relating to world history and culture are more than chance occurrences or comical absurdities. Most of the above examples would be totally unrecognisable by Russian readers

and give a new non-Russian language and culture picture of the world. They deal a serious blow to the general level of culture in our country.

Encyclopedias of this sort do nothing to raise the cultural level of the readers at whom they are aimed, but rather have an opposite harmful effect. In order to emphasise how serious and important this situation is, it is worth repeating: the avarice and profit-seeking of non-professional, unqualified publishers and equally non-professional, unqualified “translators,” who are controlled or edited by no one, cause the poor, deceived readers, for whom everything is written, translated, and published, to sink into ignorance.

After all, bilingual dictionaries, encyclopedias, and reference books are a highly authoritative and “holy” source of knowledge, which have the last word, and the magic of this word is incomparable to that of any other publication. Therefore, it is not surprising that in the early 90s, this pocket encyclopedia, “translated into the Russian language,” was republished every year: Russia, which had long sat in isolation behind the Iron Curtain, “opened to the world”, “entered the world community” (the Western community) and Russia’s inhabitants rushed to the lexicographical Source of Knowledge in order to fill their lacunae of ignorance. Everything was attractive: an “encyclopedia” (brief, succinct, giving the most basic things), “Oxford” in the publisher’s address (what could be more prestigious than that?).

To conclude, proper nouns present a difficult lexicographical problem, particularly because they seem, by comparison with common nouns, deceptively easy to translate: monosemantic, denoting individual objects “without reference to their features.”

Hence, due to the careless treatment of proper nouns, the general cultural standard decreases, a blow is dealt to the national language and culture, the language and culture pictures of the world deteriorate, and, accordingly, the prestige of the country and its people suffers.

It is vital to recognise, clarify, and follow the traditional denomination and pronunciation of historical figures, geographical names, biblical characters, and so on – that is, the entire culturally significant field of background knowledge covered by proper nouns.

So far in my brief survey of the recent changes, problems and challenges caused by the ever-increasing penetration and influence of English, I have concentrated mostly on the “losses” to the Russian language and culture. However, to be fair, I must do justice to the positive side of this influence. I can see it mainly in the very important field of communication style which is becoming more polite and civilised.

The habitual orders of the Soviet years telling people (“the broad masses of the people” in the old terminology) what to do, how to behave, how to live, were expressed invariably in very direct (and, actually, rude, as we understand now) imperative forms, i.e., verbal infinitives which are used to give orders to dogs and soldiers: стоять! (to stand!), бежать! (to run!), etc. Soviet public rules and regulations were linguistically expressed in the same way: не курить (don’t smoke – not to smoke), не сорить (don’t litter – not to litter), etc.

The new, much more decent and polite manner of administrative talking to people has come to a New Russia as a pleasant surprise. Nowadays, our “good old” order не курить (don’t smoke!) is replaced by a variety of polite appeals: у нас не курят (we do not smoke here), спасибо,

что вы не курите (thank you for not smoking here). Don’t

FOCUS ON LANGUAGE |

|

English |

|

|

45 |

|

|

December 2014 |

litter is now often expressed in a moralising way: Clean is not where you sweep, clean is where you do not litter.

Another polite novelty in the field of addressing the public is the appearance of apologies for “temporary inconvenience” at building sites, etc.

This tendency to be direct and outspoken (or rather just plain rude) in all spheres of life, including especially, for obvious reasons, commerce and business, is humorously presented by the internet “Russian-English Dictionary of Business Communication” (no authors given). This humour – alas! – is pretty true to life. However, laughing at our negative sides is a good and promising thing.

Русско-английский словарь по деловому общению:

Russian |

English Translation |

|

1. |

Господи, это опять вы.... |

1. Thank you very much for your |

God damn it, you again!... |

email. |

|

2. |

Вы читать умеете? |

2. You can find this information |

Can’t you read? |

below. |

|

3. Мылучшесделаемэтосами. |

3. Thank you for your kind assist- |

|

We’d rather do it ourselves. |

ance. |

|

4. |

Ой-ой, напугал! |

4. We regret to know that you are |

Wow, am I scared! |

not satisfied with our services. |

|

One more – last but not least – example of the positive influence of English on Russian is the change in the style of academic writing. Before Perestroika in the early 1990’s, academic papers were written in a very rigorous, deliberately impersonal style. This was achieved by many stylistic devices: an abundant use of Passive Voice, a strict prohibition of the use of I which corresponded to the Russian collectivist culture. The so-called “modest we” (русское “мы скромности”) substituted for I even when the paper was done by a single author. Now, under the influence of English the situation is changing, and academic papers, especially those meant for educational purposes, are written in a more free and attractive, easy-to-understand way. I appears more and more frequently, and this paper is evidence of this new trend.

I feel very positive about this change because, first, I, establishing closer contact between the author and the reader or listener, ensures greater efficiency of communication, and, second, the modest we is a good way to hide one’s personal responsibility for what has been said or written while using I makes one fully responsible for the content of the paper.

This is a very brief account of the ever-growing presentday influence of English on the Russian language and culture, every example of which requires a chapter of its own. It is written by a Russian academic, “advanced in years”. The young in Russia, probably, see the process and its results in a somewhat different way.

Notes:

1Trubachov, O. N., “The Russian Encyclopedia and its Antipodes: Hutchinson’s Pocket Dictionary” – Russian Philology. № 3, 1997

By Svetlana Ter-Minasova, Moscow State University

English FOCUS ON LANGUAGE

46 Translation and the Dynamics

December 2014

of Russian Literary Tradition

The impact of translation on the development of Russian literature is a vast and fascinating topic. In this brief exploration I will confine myself to translation into Russian and touch on the following questions. What roles has translation played in the dynamics of the Russian literary tradition? What were the main attitudes and driving forces in this field? Were these consistent or did they vary over time? To what extent has the situation changed in the post-Soviet contemporary cultural context?

In translation many features of the original are inevitably lost, while several new elements, absent from the original, enter the translated text and take on a new life of their own within the receiving culture. Interestingly, the Russian term ‘perevod’ (from the verb ‘perevodit’, ‘to lead, convey, or guide’ something over to the other side) suggests a more active process than the English term ‘translation’ (derived from the passive participle ‘translatus’ of the Latin verb ‘transferre’, ‘to move from one place or language to another’). In Russian culture the act of translation not only shapes the perception of the translated ‘other’, but also – and this is crucial – serves to define the translating ‘self’ as well. In other words, through translation, Russia creates its own self-image and defines itself as much as – if not more than – the other culture. Translation becomes not so much a glass to look through as a reflecting mirror in which to gaze upon one’s own image.

I would suggest that the activity of translation has played a particularly important role in Russia – more so than in other European literatures. Why was this so? Russia’s anxiety over its relatively late entrance onto the literary scene and the common perception of its ‘backwardness’ naturally fuelled its desire to make up for lost time and to ‘catch up’ with the West. Translation was promoted as a primary means of overcoming a sense of cultural isolation, in relation to the past as well as the present. Through the translation of earlier works the major phases of classical, medieval and Renaissance culture that Russia had not lived through could be assimilated and become part of an extended ‘native’ tradition. And through the translation of more recent or contemporary works, Russia could establish its place in the broad family of European literature.

Peter the Great’s programme of reforms for the Westernisation of Russia could perhaps be described as the most ambitious state-driven ‘translation project’ ever undertaken. It spawned far-reaching consequences which informed the nineteenth-century debate between

the Westernisers and the Slavophiles, ran through the Soviet period, and continues to be felt today. Over the last three centuries, translation served as one of the key vehicles through which Russia sought to define its identity in relation to the West and to develop its understanding of literature. Drawing on a range of examples, I will argue that this relationship evolved over time, but remained central and was shaped by certain constants. I will conclude by offering a few thoughts on the rather different conditions that apply in the present post-Soviet era.

Let us start by examining the early formative stages of Russian literature. The practice of translating psalms into the vernacular, prevalent in Europe from at least the sixteenth century, was taken up in Russia in the late seventeenth century, inspired by Polish examples. In 1680 Simeon Polotskii (1629–1680), Russia’s first professional court poet, produced a rhymed Psalter (Psaltyr’ rifmotvornaia), graced with a frontispiece showing King David, standing next to an open book and lyre, looking upwards in prayer to receive the gift of prophecy.

This work was tremendously influential and gave birth to an entire new tradition. During the eighteenth century, virtually every significant Russian poet composed versions of the psalms and spiritual odes in the manner of the Psalter. In 1743, Lomonosov, Trediakovskii (1703–1769) and Sumarokov (1718–1777) held a famous competition to render Psalm 143 into Russian; all three versions were published anonymously in the following year. These and subsequent translations were variously referred to as ‘versions’(‘perelozheniia’), ‘paraphrastic odes’ (‘parafrasticheskie ody’) or even ‘spiritual odes’(‘dukhovnye ody’) and formed a model for the composition of original Russian verse – in fact, as indicated by these terms, the boundaries between translation, adaptation and original composition were very fluid. Russian literature was thus shaped by a competition for the best translation.

Although the practice of translating the psalms continued to flourish, from the start it met with considerable opposition, attracting critical comment from several quarters, including religious authorities and state rulers, backed up by the censors. Simeon Polotskii’s Psalter was attacked by members of the Church as heretical, since any departure from the canonical Church Slavonic text was considered sacrilegious. In 1734, Trediakovskii tried to counter this view by arguing that translating the psalms into the vernacular would rather

provide a model for elevating literary, poetic Russian to the level of a holy language; in other words it would extend – rather than diminish – the sphere of the sacred.1 He even hinted that Russian poets who model their work on the psalms might rise to the status of the original prophet, King David.

I have dwelled on the example of translation of the psalms because it is particularly revealing. It teaches us three important points. First, translation lay at the very root of Russian literature. Secondly, the translation of psalms established the right of Russian writers to assimilate the sphere of the sacred into the literary domain. And last but not least, this practice gave rise to one of the main driving forces behind Russian literary tradition: the image of the writer as a moral and religious prophet, a successor to David, and a dissident force that could oppose the state. Without these translations, Pushkin’s ‘Prophet’ (‘Prorok’, 1826) and the numerous responses it provoked would not have been written.

My second group of examples is drawn from Pushkin and is designed to reveal a further aspect of the relationship between translation and literary practice: the way that translations were primarily valued for their impact on Russian literature, rather than for the window they opened up into other worlds. This relates to my earlier point about translations defining the translating ‘self’ more than the translated ‘other’.

When Gnedich’s translation of Homer’s Iliad appeared in 1829, Pushkin greeted it as a new Russian Iliad which would undoubtedly exert a major influence on his native literature: ‘Наконец вышел в свет так

FOCUS ON LANGUAGE English

47

December 2014

давно и так нетерпеливо ожиданный перевод “Или-

ады”! <...> Русская “Илиада” перед нами.’2 The emphasis here is not on Homer’s work per se, but on the role that the Russian Iliad will play in Russia.

Pushkin’s note of 1830 impatiently anticipating the publication of Viazemskii’s translation of Benjamin Constant’s Adolphe (1816) reflects exactly the same approach. After introducing the novel through the prism of his own work (quoting a stanza from Evgenii Onegin to characterise Adolphe as one of ‘two or three novels’ depicting contemporary man with his ‘immoral soul’), Pushkin wondered how the translator’s experienced pen would ‘conquer the difficulty’ of French, described as a ‘metaphysical language’ (the reference to translation as a form of conquest is in itself significant) and concluded: ‘В сем отношении перевод будет ис-

тинным созданием и важным событием в истории

нашей литературы.’3

So far, these examples have illustrated an enthusiastic receptivity to other cultures (biblical, classical antiquity, contemporary European) with a clear emphasis on their positive contribution to Russian literature. There was, however, another side to the coin: fierce opposition to the assimilation of foreign elements into Russian tradition. In the reign of Catherine the Great, when Peter’s ‘translation project’ had borne fruit and the fashion for Western ways, language, dress, behaviour had become established as a new ‘norm’ in Russian society, the poet and playwright, Denis Fonvizin – himself, ironically, the descendant of Russianised Germans and a proficient translator from French and German – mercilessly satirised the results. In his play The Brigadier (‘Brigadir’, 1769) he presented a case of terminal Gallomania in the idiotic young Ivanushka who thinks he has acquired a French soul because he has been to France and that he is therefore superior to ordinary Russians. Fonvizin attacks the Westernising mentality, showing how it has fundamentally corrupted Russian society, destroying the integrity of its language, morals, and relations between the generations (when Ivan addresses his father as ‘mon père’, the father cannot understand what he is saying). Although the focus in contemporary Russia has switched from French to English, the anxieties about the preservation of national identity and language in the face of creeping Westernisation remain the same.

Some sixty years later, Petr Chaadaev took Fonvizin’s points further. In his philosophical letter of 1829

English |

FOCUS ON LANGUAGE |

48

December 2014

(published in 1836), paradoxically written in French, he castigated Russians as ‘illegitimate children without a heritage’, ‘strangers to our own selves’, unable to hold on to the past, lacking any goal, and possessing only superficial knowledge – all presented as ‘a natural consequence of a culture based wholly upon importation and imitation’.4 The problem is clear: how could a culture so heavily dependent on the imitation of Western models, for which translation served as the prime conduit, be seen as organic and original? Could an authentic ‘Russian soul’ be identified and survive amongst all these Western borrowings? This anxiety underpins Tatiana’s suspicions that her beloved Evgenii Onegin is no more than an empty ‘imitation’ or ‘parody’, ‘a Muscovite in Harold’s cloak’ (Evgenii Onegin, VII, 24), countered by Lermontov’s defiant claim in his poem of 1832:

Нет, я не Байрон, я другой, <...>

Но только с русскою душой.

Chaadaev’s provocative letter prompted several responses. The Slavophiles retaliated by rejecting the Westernising path as inferior and insisting on the primacy of Russian customs. In the late 1870s Dostoevskii came up with a way to reconcile the two sides of this binary ‘us or them’ opposition. Citing Pushkin’s talent for echoing other cultures as a model to validate his ideal, he argued that an openness to foreign influences, reflected in the poet’s alleged qualities of ‘universality and all-humanity’ (‘vsemirnost’ i vsechelovechnost’’), was central to the Russian spirit; Russia’s mission therefore lay in assimilating and reworking the legacy of other nations in order to return it to the rest of the world in a uniquely ‘spiritualised’ Russian form.5

Dostoevskii’s approach enabled the reconciliation of outward-looking translation activity with a Russocentric prophetic mission that was both national and universal (a synthesis that neatly reflected the legacy of translating psalms). It underpinned the remarkable explosion in the sphere of translating that took place at the turn of the century during the Silver Age, marked by the large number of publishing-houses that launched special series of world literature in translation, covering works from classical antiquity through the middle ages to the Renaissance, as well as nineteenth-century and contemporary European writing.

Despite the overt appeal to ‘other’ cultures, these translations were in fact almost invariably driven and defined by purely Russian preoccupations. For example, the leading Symbolist Viacheslav Ivanov, widely acclaimed as a true ‘Russian European’, used his trans-

lations of Dante to refashion the medieval poet in the light of his own Dionysiac and Solov’evian views, proclaiming enthusiastically to his readers in 1914: ‘Итак,

Данте – символист!’6

The relationship between translation and the dynamics of Russian literary tradition during the Soviet period is a complex one. The official approach built on the existing initiatives and enthusiasm for translation, but gave these a new political twist. Dostoevskii’s idea of the Russian universal mission to humanity morphed into the ambitious Soviet project of receiving and disseminating world culture, filtered through the prism of the regime’s ideology. This manifested itself in many ways, including extensive state support for publishing-houses such as Vsemirnaia literatura, founded in 1918 by Maksim Gorky and absorbed into

Gosizdat in 1925, or Izdatel’stvo Tovarishchestva inostrannykh rabochikh v SSSR, set up in 1931 and given a new lease of life as Progress from 1963. New journals were set up such as Za rubezhom in 1932, and Inostrannaia literatura in1955, following a series of earlier versions discontinued in 1943. A dedicated State Library of Foreign Literature, popularly known as the ‘Inostranka’, was founded in 1924 and is now home to a range of cultural exchange institutions including the British Council. The state actively promoted the translation of literatures from within the Soviet Union, the Eastern European bloc and likeminded regimes, and also supported selective translation of foreign works. Soviet expansion and cultural imperialism went well together.

What of unofficial responses? The state-sponsored translation projects provided a creative outlet and source of income for writers of the previous generation who faced increasing difficulties in publishing their own work after the late 1920s. Pasternak’s celebrated translations of Shakespeare not only enabled him to earn a living, they also opened up a vital channel of cultural communication between Russia and Britain during the war years and allowed the poet a measure of free expression. In his rendition of Hamlet’s ‘To be or not to be’ soliloquy Pasternak introduced some telling new phrases, absent from the original, such as ‘ложное

величье правителей, невежество вельмож, / Всеоб-

щее притворство’ (‘the sham grandeur of rulers, the ignorance of magnates, / Universal pretence’) – thinly veiled attacks on the cult of personality and the lackeys of Stalin’s regime. If we add to this the performance element – these lines were, after all, declaimed on stage to audiences in Stalinist Russia – and recall that Pasternak’s work on translating Hamlet was directly linked

to the genesis of Doctor Zhivago in 1945, the novel that he regarded as the high point of his literary career

– then we can begin to appreciate the full significance of translation in the dynamics of the literary process in Russia.

More broadly, translation in the Soviet years also served as a repository of cultural memory and as a refuge for intellectuals. The distinguished translator and philologist Mikhail Gasparov (1935–2005) explained that he decided to study classical antiquity in the 1950s because he regarded it as ‘a crevice in which to hide away from contemporary life’.7 The study of Russian literature was an ideological minefield, while the classics offered a more distant, less controlled intellectual space.Antiquity became a type of academic ‘safe house’ for serious intellectuals in post-Stalinist times, an area where they could translate ancient texts, develop their critical skills, engage with philosophical thought, and transmit this legacy in untainted form to a new generation. Significantly, both Gasparov and Sergei Averintsev subsequently moved on from the study of classical antiquity to redefine Russian literature for their generation – Gasparov’s work on poetry and Averintsev’s essays on Viacheslav Ivanov and Osip Mandel’shtam stand out for their brilliance among a sea of mediocre Soviet literary criticism.

And now for a few closing thoughts on the legacy of this tradition in the post-Soviet period. Not surprisingly, the activity of translation continues to be dominated by the question of Russia’s relation to the West. In the initial period after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the privatisation of publishing houses, the need to ‘catch up’ after seventy years of iron curtain isolation resulted in the market being flooded with translations – often of low quality Western mass literature. Was this perceived as a welcome opening up, or as a dire threat to the preservation of a ‘morally superior’ Russian culture? Would Fonvizin’s opposition to the mindless Westernisation of his day be redeployed?

In an interview conducted in May 2014 Liudmila Ulitskaia contrasts the period of ‘great hopes’ (under Eltsin), when Russians thought they would finally be reunited with the stream of world culture (‘mirovoi protsess’), and the current pain of finding that they are being returned to ‘complete cultural and political isolation’. She pours scorn on an ‘Orwellian’ document recently produced by the Ministry of Culture, the essence of which appears to be that Peter the Great made a mistake, Russia is not Europe and should not attempt to be, Europe is harmful, and Russia should turn away from it in order to preserve its ‘superior’ values.8

FOCUS ON LANGUAGE English

49

December 2014

So, what can we conclude from this giddy troika ride through the Russian landscape of translations? From its beginnings translation has remained central to Russia’s definition of its self-image and relation to the West. The psalms set this in motion and incidentally provided the model of the writer-translator as poet-prophet. Pushkin demonstrated an appetite and talent for the creative reception and assimilation of other cultures into Russian literature. Despite – or perhaps because of – Chaadaev’s opposition to a culture of importation and imitation, Dostoevskii turned this phenomenon into a universal Russian mission, which was subsequently embraced, politicised and institutionalised by the Soviet state. It remains to be seen to what extent the current political regime will try to control – or perhaps be controlled by – the free space offered by cultural exchange and translation. In the age of the Internet and increasingly globalised cultures, this two-way relationship has become more powerful than ever before. One thing remains clear: translation will certainly continue to play a crucial role in defining the dynamics of Russian literary tradition.

Notes:

1‘Rassuzhdenie o ode voobshche’, in Vasilij Kirillovič Trediakovskij, Psalter 1753, ed. Aleksander Levitsky, Paderborn, 1989, p.539.

2Literaturnaia gazeta, 1830, no. 2, cited from A. S. Pushkin, Sobranie sochinenii, ed. D. D. Blagoi, 10 vols., Moscow, 1974-1978, vol.6, p.29.

3Literaturnaia gazeta, 1830, no. 1, cited from Pushkin, Sobranie sochinenii, vol.6, p.29.

4P. Ia. Chaadaev, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii i izbrannye pis’ma, Moscow, 1991, pp.91-92.

5Dostoevskii first elaborated this idea in his writer’s diary of 1877, and then – most famously – in his Pushkin speech of 1880.

6‘Ekskurs: O sekte i dogmate’, in Viacheslav Ivanov, Sobranie sochinenii, ed. D. V. Ivanov and O. Deschartes, 4 vols., Brussels, 1971–1987, vol.2, p.613.

7Mikhail Gasparov, Zapisi i vypiski, Moscow, 2000, p.314.

8Interview conducted by Evgenii Levkovich on 24 May 2014, at http://oromanova.org/f/lyudmila-ul- ickaya-ne-udivlyus-esli-zavtra-v-obixod-snova-bu- det-vveden-termin-vrag-naroda/.

Pamela Davidson,

Professor of Russian Literature

University College London, School of Slavonic and

East European Studies

English |

|

FOCUS ON LANGUAGE |

|

50 |

|

Adapting or Adopting – The Dilemma |

|

December 2014 |

|

||

of Today’s EFL Teaching

In today’s world, English has really become a lingua franca predominantly used by non-native speakers in communication with other non-native speakers. In professional discourse, especially academic discourse, it is often supported by secondary semiotic systems like symbols, formulae, graphic and visual aids. International terminology is the backbone of professional communication. But does that mean that we can teach international English divorced from the culture of English-speaking peoples to all categories of language learners? Is this approach of adapting a natural semiotic system to the pragmatic needs of communicants with limited specific needs justified in pre-service training of language specialists – linguists, language teachers and especially translators and interpreters? Why is cultural component a must in language programmes for humanities students? How does understanding culture help to master grammar?

When we speak of how the world view is reflected in language, we usually refer to vocabulary. We all know classical examples of 20 adjectives for the white colour of snow in the Innuit language, or a variety of terms for a camel in Arabic. Idioms is another well-researched field. We all know the metaphors we live by, but what about grammar patterns that reflect and determine the world view of different peoples of the world?

I’d like to briefly analyse two grammatical patterns to show the connection between mental representations and grammar patterns. One of them is the way we describe the future in Russian and in English. Teachers of English know how difficult it is to make Russian students use the whole variety of English future forms in their speech, especially spontaneous speech. The students will make no mistakes in exercises and in writing, but when it comes to speaking, they will tend to use one or, at best, two forms. The obvious explanation lies in the fact that in Russian we have one form for future. But actually it’s much more complicated than that: it’s difficult for us to differentiate between future intentions, future plans, future plans with some arrangements already done, etc. In our world view future is future and whatever your plans and arrangements may be, still Russian wisdom says “Человек предполагает, а Бог располагает” – “Man proposes, God disposes”. In the country where the past is vague and obscure the future is unpredictable. So, to help our students to use future forms in English correctly, we have to introduce this different idea of describing future, we have to re-structure their world view in a way.

Russian fatalism as a national trait is deeply embedded in the language. The idea of personal, individual re-

sponsibility is somewhat alien to Russian mentality, and that explains the fact that there are so many types of sentences with no agent at all or the agent is unknown, or the agent is everyone and no one in particular. English sentence structures focus on agents and this difference adds to the untranslatable in Russian-English translation. Imagine a situation when a Russian student comes home after an especially difficult exam. When asked, “Have you passed? How did it go?” she or he says in Russian, “Не сдается!” This impersonal sentence shows the exam (and the student’s failure) as a natural phenomenon which is beyond human power. The student doesn’t blame the examiner, saying “He failed me”. The student doesn’t take the responsibility for he failure either; and doesn’t say “I failed the exam.” The student prefers the impersonal construction which is not a regular way of expressing the idea but follows a common pattern to show that this failure is in the natural order of things. If I were making my presentation in Russian and just mentioned this anecdote, it might have caused difficulties for interpreters. The closest I can think of, is a very clumsy phrase, “The exam failed itself”.

Please, don’t misunderstand me. I don’t mean to say that Russian, or English, is poorer in its grammar resources. The point I’m trying to make is that Russian and English are different in their grammar patterns and their world views and to really understand grammar, we should think of culture. You may ask me “Do the languages we speak shape the way we think? Do they merely express thoughts, or do the structures in languages (without our knowledge or consent) shape the very thoughts we wish to express?” I think, Svetlana Ter-Minasova gave the answer to this question some 25 years ago in her book “Language and Cross-Cultural Communication”. The language reflects the culture and the world-view of a given language community, and at the same time, the language shapes the cultural assumptions, beliefs, expectations, attitudes, norms and values of this community. In this respect, varieties of English used in different countries as the first language, or the mother tongue do differ, but still there are some inherent non-variable characteristics common to all of them. We all know that the British and the Americans have much in common but the language, “The Americans are identical to the British in all respects except, of course, language.” (Oscar Wilde). “We (the British and Americans) are two countries separated by a common language.” (G. B. Shaw)

When people learn another language, they also learn a new way of looking at the world. In our English cours-

es and our courses in English–Russian translation and interpreting, we aim at a meaningful awareness of other cultures, together with a deeper understanding of our own. When a language teacher, language researcher, translator or interpreter switches from one language to another, they start thinking differently, too. In training language specialists we cannot limit ourselves to comparing merely language structures or vocabulary items. We should get an insight into the underlying cultures, the underlying world views. It’s the only way to lay a sound foundation for professional development and ensure success for our students.

So, my answer to the dilemma of adapting or adopting is – it depends. For non-language specialists, for

FOCUS ON LANGUAGE English |

51 |

December 2014 |

general English communication, I think adapting the language is a logical solution (international English is a kind of adaptation, isn’t it?). For humanities students, for language specialists in particular, the answer to the dilemma is different. For them, adopting another language and another culture, another world view as it is represented in the language is a must. This is the approach elaborated at Moscow State University, developed by Svetlana Ter-Minasova and her followers. We try to teach our students to “take off their Russian glasses” and to view and examine the culture associated with the English language from within.

Maria Verbitskaya

Getting to Grips with Changes

in the English Cultural World View

For communication to be successful, the speaker and the hearer need common cognitive space. This is created by a common conceptual world view (CWV).

The CWVs of different cultures do not coincide, they may overlap, and the greater the common overlapping area is, the more successful the understanding between two cultures is.

The Russian and English conceptual world views coincide in most sectors because of certain common shared values characteristic of the present historical epoch. Both conceptual world views may be deficient in some respects and commonnalities can be lacking in some concepts.

For the past three decades, the list of the basic concepts of human society (“the alphabet of human thought”) has not been changed greatly (cf.: the list suggested by R. Jackendoff (1983): “thing”, “place”, “time”, “direction”, “action”, “manner”, “amount”, “smell”, etc.). But some of these concepts have been expanded or changed.

The concepts of physical space and time have been changed due to improved communication and global networking, e.g. telecommuting – the practice of working at home but being connected to one’s office through computer; telebanking – bank transactions made from a home computer. Cf.: “The office blocks will be deserted as the workers telecommute in the suburbs” (Safire, 1996). As a result of changes in the concept of time for the past thirty years a new conceptual metaphor has appeared: time is a solid structure which can be deformed

or distorted. For example, time-warp – an imaginary discontinuity or distortion in the flow of time. The concept of time as a physical entity having form can be illustrated by such examples as time-frame – a defined period of time in which something is planned to happen, window spaces of spare time in a schedule or timetable; cf. time-slot, time-slice.

The traditional domain of criminal activities has been enriched by the new concept of “gangsta” (collective criminality) which has become a separate sub-domain functioning as a general term for a group of such words as steaming (activity of passing rapidly in a gang through public place, robbing bystanders by force of number), wolf-pack (a group of marauding young people engaged in mugging) and wilding (a kind of violent robbing), cf. jamming, drive-by, side-walking. So we can speak about changes in the prototype of the criminal.

The domain of health care has been enriched by the new concept “a complex of syndromes”, which in its turn, has become a more general term for such words as “the 20th century syndrome” (a complex of syndromes based on the stress and strain of the 20century), “agoraphobia” (a complex of fears – fears of open spaces, bridges, crowds in the shops, etc.), “tight/sick building syndrome” (a complex of allergies caused by artificial materials used in modern construction works).

Among other traditional domains most actively enriched by new concepts mention should be made of money and finance, politics, music, arts, and drug abuse.