mrc

.pdf

|

Harvard Business School |

9-274-118 |

|

||

|

||

|

|

Rev. June 30, 1982 |

|

|

|

MRC, Inc. (A)

In late March 1961, Archibald Brinton, president of MRC, Inc., was grappling with the question of whether to acquire American Rayon, Inc. (ARI). Brinton was troubled by ARI’s erratic earnings record and mediocre long-term outlook, but recognized that MRC could benefit greatly from ARI’s liquidity and borrowing capacity. He was therefore inclined to go through with the acquisition, provided ARI could be purchased at a price that would allow MRC an adequate return on its money.

Background Information on MRC

MRC was a Cleveland-based manufacturing concern with 1960 earnings of $3.9 million on sales of over $118 million. The most important product lines were power brake systems for trucks, buses, and automobiles; industrial furnaces and heat treating equipment; and automobile, truck, and bus frames. Exhibit 1 presents data on the operating results and financial position of MRC.

Diversification Program

Upon becoming chief executive officer in 1957, Brinton had begun an active program of diversification by acquisition. The need for rapid diversification seemed compelling. Until 1957 virtually all sales were made to less than a dozen large companies in the automotive industry; car and truck frames accounted for 85% of the $70 million sales total in 1956. As a result, earnings, cash flow, and growth were constantly exposed to the risks inherent in selling to a few customers, all of which operated in a highly cyclical and competitive market. Previous attempts at internal diversification had foundered on management’s lack of expertise in markets and technologies outside the automotive area. Brinton therefore turned to acquisitions as a means of buying up established sales and earnings as well as managerial and technical know-how. In his words, the acquisition strategy was intended to:

1.achieve related diversification and thus lessen vulnerability to technological change in a single industry;

2.stabilize earnings and cash flow;

This case was prepared as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation.

Copyright © 1974 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, call 1-800-545-7685, write Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, MA 02163, or go to http://www.hbsp.harvard.edu. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the permission of Harvard Business School.

1

274-118 |

MRC, Inc. (A) |

3.uncouple growth prospects from the cyclical and unexciting automotive industry; and

4.escape the constant threat of backward integration by one or more major customers.

The drive for diversification was intensified in 1959 when Chrysler announced a move toward unitized (i.e., frameless) body construction.

By the end of 1960 the diversification campaign had resulted in five acquisitions, two of which were major transactions. Acquisition of Ross Engineering increased MRC sales by $27 million in 1957, and the purchase of Surface Combustion in 1959 added about $38 million to annual sales. The company’s acquisition history is shown in Exhibit 2. Significantly, total sales increased almost $50 million between 1956 and 1960, despite a $30 million decline in automotive sales over that period.

Management Structure

While the diversification program had reduced MRC’s dependence on a single industry, it had also created significant strains on the company’s organization structure and financial position.

As the acquisition program carried MRC into wider markets and technologies, it became increasingly apparent to management that the company’s highly centralized decision-making processes were ill suited to the needs of a diversified corporation. By the end of 1959, it was clear that the headquarters management group could not acquire or maintain detailed knowledge of all the products, markets, and technologies embraced by MRC. Because the company considered continued rapid diversification imperative, it shifted to a highly decentralized management structure, which transferred substantial decision-making power to division managers.

In 1961, MRC consisted of seven divisions. All marketing, purchasing, manufacturing, research and development, personnel matters, and accounting were handled at the division level. Each division had its own general manager (usually a vice president), who reported directly to Archibald Brinton and had the primary responsibility for the growth and profitability of that division. A division manager could get stock options and earn an annual bonus of up to 60% of his or her base salary, depending on the earnings and growth of the division. Divisional sales and earnings goals were formally defined in an annual budget and in a rolling five-year plan, which were drawn up by the general managers and submitted each November to the head office for review by Brinton and the corporate staff.

The corporate staff provided legal, administrative, and financial support to the divisions and handled external affairs, financing, and acquisitions as well. The staff, including corporate officers, numbered fewer than 60 people, about half of whom were secretarial and clerical employees.

Brinton felt that he could exercise adequate control over the decentralized organization through his power to hire and fire at the division manager level and, more importantly, through control of the elaborate capital budgeting system. Appendix A discusses MRC’s capital budgeting procedures.

No acquisitions were made in 1960. But by 1961, Brinton was confident that the organization was capable of smoothly assimilating new operations, and his staff had identified and opened preliminary discussions with several attractive acquisition prospects. The financing of past acquisitions, however, had created pressing financial problems.

2

MRC, Inc. (A) |

274-118 |

Finances

The acquisition campaign had been hampered from the outset by MRC’s low price-earnings (P/E) multiple. Although growth was an explicit objective of the acquisition program, MRC could not exchange its shares for those of high P/E growth companies without severely reducing earnings per share. It was feared that such a dilution of earnings per share would further depress the P/E ratio, making it still more difficult to swap stock with growth companies. Consequently, MRC had relied heavily on debt financing for most of its acquisitions.

By early 1961, MRC had largely exhausted its borrowing capacity. Between 1956 and 1960, long-term debt had risen from less than $4 million to more than $22 million. Although it appeared that capital expenditures planned for 1961 could be funded with internally generated funds, the near exhaustion of debt capacity posed a serious threat to the acquisition strategy. Discussions with commercial banks, life insurance companies, and investment bankers had made it clear that without a substantial infusion of new equity, any further increases in long-term debt would be extremely difficult, and probably impossible. Investment bankers had further pointed out that long-term lenders would probably insist on severely restricting the company’s flexibility to make cash acquisitions, even if it should prove feasible to raise new debt. With MRC near its debt limit and the P/E ratio around 10, the entire diversification campaign was in danger of collapsing.

ARI, with its $20 million worth of marketable securities, appeared to provide a convenient new source of funds with which to fuel the acquisition program.

Background Information on ARI

American Rayon, Inc., a Philadelphia-based corporation, was the third largest producer of rayon in the United States.1 In 1960 ARI had recorded sales of $55 million and a pre-tax profit of $5 million, after three years of severe profit problems (see Exhibits 3 and 4). By early 1961 the company’s stock was trading on the New York Stock Exchange at less than half of book value and top management feared that the company’s new-found profitability, along with its great liquidity and a disenchanted shareholder group, would make ARI attractive to raiders. Consequently, management was seeking to arrange a marriage with a congenial partner. ARI’s investment banker had brought the company to the attention of Archibald Brinton, who had expressed tentative interest in a deal.

Acquisition Investigation

The results of MRC’s investigation of ARI were mixed. On the plus side, ARI had over $20 million in liquid assets that were not needed for operations, no shortor long-term debt, and a modern manufacturing facility. It appeared that the company could be purchased for about $40 million worth of MRC common stock. Moreover, although ARI top management was not young, James Clinton, the 64-year-old president, was willing to stay on for two years after the acquisition to give MRC personnel a chance to learn the business before his retirement.

On the other hand, the longer-term outlook for rayon was grim. This industry had enjoyed one of the most spectacular successes in the history of American enterprise. For example, the American Viscose Corporation, which founded the rayon business in 1910, achieved in its first 24 years aggregate net earnings of $354 million, or 38,000% of original investment, while financing rapid

1 Rayon is a glossy fiber made by forcing a viscous solution of modified cellulose (wood pulp) through minute holes and drying the resulting filaments.

3

274-118 |

MRC, Inc. (A) |

expansion entirely out of earnings.2 But rayon began to falter in the early 1950s as competing synthetics such as nylon and acrylic became popular. Style and fashion shifts also made cotton more attractive. The net effect was to force production cutbacks in rayon, and by the end of the 1950s many companies, including Du Pont, had withdrawn from the rayon industry altogether.

With shrinking industry volume, ARI experienced increasing earnings difficulties. These difficulties could be traced directly to the declining use of rayon in automobile tire cord, the market accounting for upwards of 60% of ARI’s output. First tried in tire construction in 1940, rayon reached an annual peak in tire manufacture around 1955.3 With the advent of nylon cord, rayon’s market share of this application began to decline. Between 1955 and 1960, rayon’s share of the total tire cord market dropped from 86% to 64%, and the total number of pounds of rayon used in tires dropped 38% (see Exhibit 5).

Prospects for ARI

It was clear to MRC management that the mediumto long-term future held continuing decline and eventual liquidation for ARI. If purchased, ARI could not be expected to contribute to the MRC growth objectives, and in time it might well become a serious drag on earnings. Consequently, Brinton was somewhat leery of pushing through to an acquisition, which he feared might entangle MRC in a dying business. In any case, he knew that MRC management lacked the technical knowhow to contribute to the profitability of ARI. Moreover, he was not at all sure that the recently overhauled organization structure could easily assimilate a company as large as ARI. Thus he was reluctant to move quickly, whatever the discounted cash flow-return on investment (DCF-ROI) numbers might show.

However, the near-term picture, as presented by Richard Victor, vice president for mergers and acquisitions, was not entirely unappealing. Although losses were sustained in 1957 and 1958, the company had subsequently returned to profitability as a result of substantial reductions in overhead, sale or liquidation of marginal and unprofitable operations, streamlining the marketing and R&D organizations, and consolidating production in a new manufacturing facility. On the basis of the investigation and analysis of his staff, he estimated that ARI would be able to maintain current volume, prices, and margins through 1964, thereafter experiencing annual sales declines of 10% to 15%. He also estimated that assumption of numerous staff responsibilities by the MRC corporate staff would add about one percentage point to ARI’s before-tax profit margin. Exhibit 6 shows pro forma income statements for ARI prepared by the MRC acquisition team.

From a financing point of view, it was thought that capital spending needs over the next six to eight years would average no more than $300,000 annually. Victor felt that, if anything, his estimates understated future profits, since he expected ARI to pick up market share as smaller companies continued to withdraw from the rayon industry.

Valuation

At a price of $40 million, ARI looked cheap. But Brinton insisted that any acquisition undertaken by MRC must promise to yield an adequate return, as measured by its DCF-ROI.4 He

2Jesse W. Markham, Competition in the Rayon Industry (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1952), p. 16.

3C. A. Litzler, “The Fluid Tire Cord Situation,” Modern Textiles Magazine, September 1966, p. 20.

4This measure of effectiveness is also commonly known as the internal rate of return, the time adjusted rate of return, and the yield.

4

MRC, Inc. (A) |

274-118 |

regarded an acquisition decision as a special case of the capital budgeting decision. Like a capital budgeting project, an acquisition required the commitment of economic resources, cash or common stock or debt capacity, in the expectation of realizing a future income stream. Consequently, the primary valuation procedure used in acquisitions was conceptually identical to the capital budgeting procedure (see Appendix A). All outlays and all cash inflows that were expected to result from undertaking a particular transaction were projected, and the DCF-ROI was found. In terms of required rates of return, acquisitions were considered to be very similar to new product introductions.

As Brinton pondered the acquisition problem, he also considered management’s forecast of MRC’s per share income (Exhibit 7). MRC’s common stock had closed the day before at 14 1/2. ARI had closed at 15.

5

274-118 |

MRC, Inc. (A) |

Appendix A

Capital Budgeting Procedures of MRC, Inc.

The formal capital budgeting procedures of MRC were outlined in a 49-page manual written for use at the divisional level and entitled “Expenditure Control Procedures.” This document outlined (1) the classification scheme for types of funds requests, (2) the minimum levels of expenditure for which formal requests were required, (3) the maximum expenditure that could be authorized on the signature of corporate officers at various levels, (4) the format of the financial analysis required in a request for funds to carry out a project, and finally (5) the format of the report that followed the completion of the project and evaluated its success in terms of the original financial analysis outlined in (4).

1. Classification Scheme for Funds Requests

The manual defined two basic classes or projects: profit improvement and necessity. Profit improvement projects included:

∙cost reduction projects;

∙capacity expansion projects in existing product lines; and

∙new product line introductions.

Necessity projects included all projects whose basic purpose was not profit improvement, such as those for service facilities, plant security, improved working conditions, employee relations and welfare, pollution and contamination prevention, extensive repairs and replacements, profit maintenance, and services of outside research and consultant agencies. Also included in this class were expense projects of an unusual or extraordinary character that did not lend themselves to inclusion in the operating budget and could normally be expected to occur less than once per year.

2. Minimum Amounts Subject to Formal Request

Not all divisional requests for funds required formal and specific economic justification. Obviously, normal operating expenditures for items such as raw materials and wages were managed completely at the level of the divisions. Capital expenditures and certain recurring operating expenditures were subject to formal requests and specific economic justification if they exceeded certain minimum amount levels specified below.

Project Appropriation Requests were to be issued as follows:

∙Capital. Projects with a unit cost equal to or more than the unit cost in the following schedule shall be covered by a Project Appropriation Request; items with lesser unit costs shall be expensed.

Land improvements and buildings |

$1,000 |

Machinery and equipment |

500 |

Tools, patterns, dies, and jigs |

250 |

Office furniture and office machines |

100 |

∙Expenses of an unusual or extraordinary character that do not tend themselves to inclusion in the operating budget and could normally be expected to occur less than once per year shall be covered by a Project Appropriation Request.

6

MRC, Inc. (A) |

274-118 |

The minimum amount at which a Project Appropriation Request for expense is required is $10,000.

3. Approval Limits of Corporate Officers

Officers at various management levels within MRC had the authority to approve a division’s formal request for funds to carry out a project subject to the maximum limitations shown below.

Approvals. Requests shall be processed from a lower approval level to a higher approval level in accordance with the chart below to secure the authorities’ initials (and date approved). Lower approvals shall be completed in advance of submission to a higher level.

|

Highest Approval |

Expense projects |

Level Required |

Minimum to $10,000 |

Division manager |

$10,000 to $50,000 |

Corporate president |

$50,000 and over |

Board of directors |

Capital projects |

|

Minimum to $5,000 |

Division manager |

$5,000 to $50,000 |

Corporate president |

$50,000 and over |

Board of directors |

Expense and capital combinations

Required approvals shall be the higher level required for either the capital or expense section in accordance with the above limits.

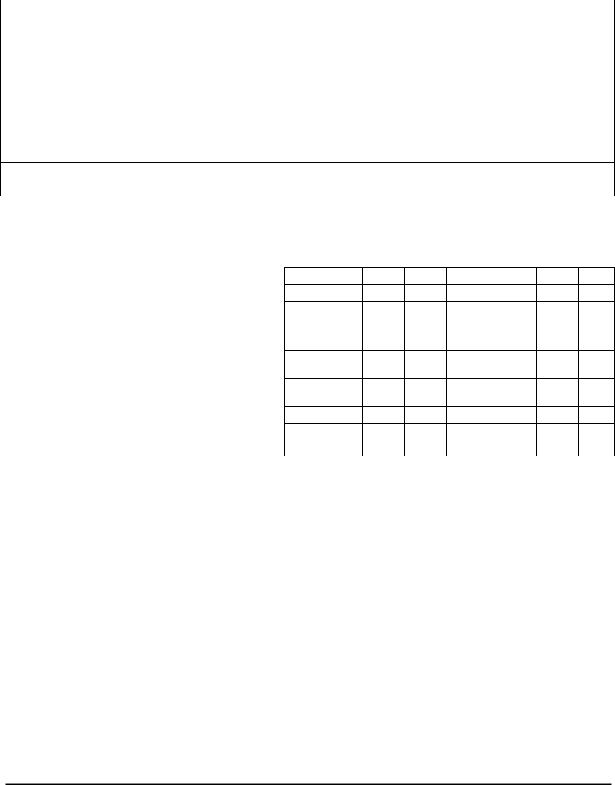

4. Project Appropriation Request

The formal financial analysis required in a request for funds was called a Project Appropriation Request (PAR). The format of a PAR is shown in Exhibit A-1. The key output factors in the analysis (which included the amount of the total appropriation, the discounted cash flow rate of return on the investment, and the payback period) are summarized on the first page of the form under “Financial Summary” for easy reference.

The PAR originated at the divisional level and circulated to the officers whose signatures were necessary to authorize the expenditure. If the project was large enough to require the approval of an officer higher than the division manager, then five other members of the corporate financial group also reviewed the proposal. This group included the controller, the tax manager, the director of financial planning, the treasurer, and the vice president of finance. These managers did not review very small projects, however, since division managers could authorize capital items under $5,000 without approval at the corporate level.

7

274-118 MRC, Inc. (A)

Exhibit A-1 Project Appropriation Request

DIVISION |

|

DEPARTMENT |

|

|

LOCATION |

|

||

Power Controls |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TITLE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disc Brake Manufacturing Facility |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PROFIT IMPROVEMENT |

NECESSITY |

|

PREDICTED LIFE |

UNDERRUN |

OVERRUN |

|

STARTING DATE |

COMPLETION DATE |

X |

|

|

15 |

|

|

|

July 1961 |

April 1963 |

|

|

|

YEARS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. DESCRIPTION AND JUSTIFICATION.

The U.S. automotive industry is experiencing a trend to the use of disc braking systems for passenger cars and light trucks. Our market research indicates this type of braking system will be widespread within 5 years and the Power Controls Division can be a major supplier of these systems if we act now to provide the required manufacturing facilities.

2. FINANCIAL SUMMARY

|

|

|

|

|

APPROVAL AND DISTRIBUTION OF COPIES |

|

|

||

|

|

PREVIOUS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THIS |

APPROVED |

TOTAL |

DIVISION |

DATE |

NO. |

CORPORATE |

DATE |

NO. |

|

REQUEST |

REQUESTS |

PROJECT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CAPITAL |

4,875,000 |

______ |

4,875,000 |

ISSUED BY |

|

|

GROUP V.P. |

|

|

Work Cap. |

1,950,000 |

1,950,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

EXPENSE |

975,000 |

|

975,000 |

TOTAL |

7,800,000 |

|

7,800,000 |

LESS |

|

|

|

SALVAGE |

|

|

|

VALUE OF |

|

|

|

DISPOSALS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NET |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK VALUE |

|

|

|

OF DISPOSALS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PROJECT BUDGETED AMOUNT |

7,800,000 |

||

|

|

|

|

RETURN ON INVESTMENT (AFTER TAX) |

16 |

||

|

|||

|

|

|

% |

|

|

|

|

CONTROLLER

TAX MANAGER

MGR. FIN.

PLANNING

TREASURER

FINANCIAL V.P.

DIVISION PRESIDENT CONTROLLER

PERIOD TO AMORTIZE (AFTER TAX) |

3.6 |

DIVISION |

|

|

|

FOR THE BOARD |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

YEARS |

MANAGER |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ACCOUNTING DISTRIBUTION |

|

|

|

PROJECT |

YES |

|

NO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EVALUATION |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

REPORT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

REQUIRED |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ESTIMATED TIMING OF EXPENDITURES BY QUARTER AND YEAR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

3/61 |

4/61 |

1/62 |

|

2/62 |

3/62 |

|

4/62 |

1/63 |

2/63 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

$75,000 |

$125,000 |

$1,125,000 |

|

$1,500,000 |

1,500,000 |

$1,875,000 |

$900,000 |

$700,000 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Form M-RC 8-10 (10/65) Sections 1 and 2

8

274-118 -9-

Exhibit A-1 (continued)

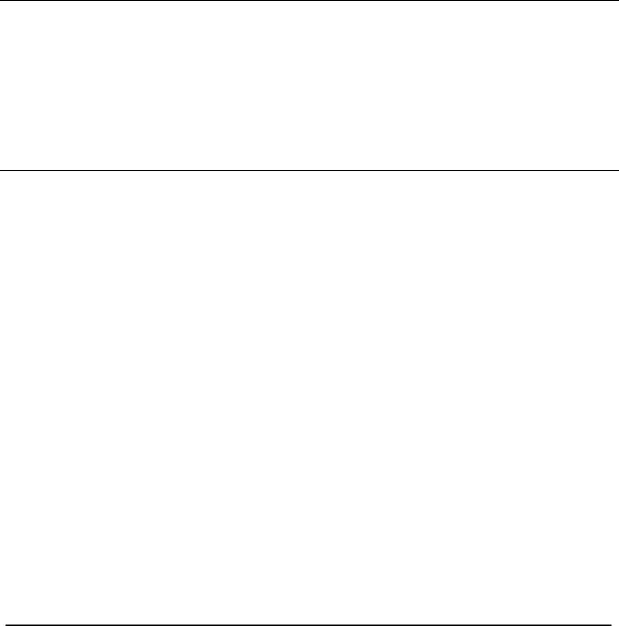

7. PRESENT VALUE OF CASH FLOWS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NUMBER SUPPLEMENT |

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15% TRIAL INTEREST RATE |

|

16% TRIAL INTEREST RATE |

|

|

% TRIAL INTEREST RATE |

|

|

|||||

YEAR |

|

|

YEAR OF |

DISBURSEMENTS |

|

CASH RETURNS |

FACTOR |

PRESENT WORTH |

|

FACTOR |

PRESENT WORTH |

|

|

FACTOR |

PRESENT WORTH |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

OPERATION |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DISBURSEMENTS |

CASH RETURNS |

|

DISBURSEMENTS |

CASH RETURNS |

|

DISBURSEMENTS |

|

CASH RETURNS |

||||

1961 |

|

|

2 PRIOR |

200 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.346 |

269 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1962 |

|

|

1 PRIOR |

6,000 |

218 |

|

|

|

|

1.160 |

6960 |

|

|

253 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BEGINNING OF OPERATIONS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

1963 |

|

|

AT1 |

1,600 |

468 |

1,000 |

|

|

xxxxxxx |

1.000 |

1132 |

|

|

xxxxxxx |

1,000 |

|

|

xxxxxxx |

||

1963 |

|

|

1 |

|

641 |

|

xxxxxxx |

|

.862 |

xxxxxxx |

|

553 |

|

xxxxxxx |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

2 |

|

1792 |

|

|

|

|

.743 |

|

|

|

1331 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

1686 |

|

|

|

|

.641 |

|

|

|

1081 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

1601 |

|

|

|

|

.552 |

|

|

|

884 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

1523 |

|

|

|

|

.476 |

|

|

|

725 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

1473 |

|

|

|

|

.410 |

|

|

|

604 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

1443 |

|

|

|

|

.354 |

|

|

|

511 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

|

1439 |

|

|

|

|

.305 |

|

|

|

439 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

1434 |

|

|

|

|

.263 |

|

|

|

377 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 |

|

1432 |

|

|

|

|

.227 |

|

|

|

325 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

|

1337 |

|

|

|

|

.195 |

|

|

|

261 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12 |

|

1241 |

|

|

|

|

.168 |

|

|

|

208 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 |

|

1241 |

|

|

|

|

.145 |

|

|

|

180 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

14 |

|

1241 |

|

|

|

|

.125 |

|

|

|

155 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

|

1400 |

|

|

|

|

.108 |

|

|

|

151 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

Return Work Cap. 1950 |

|

|

|

|

.108 |

|

|

|

210 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

15 |

Residual Plant |

885 |

|

|

|

|

.108 |

|

|

|

96 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

28 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TOTALS |

7800 |

|

24,445 |

|

|

|

|

|

8361 |

|

|

8344 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

CASH RETURNS LESS |

xxxxxxx |

|

|

|

xxxxxxx |

|

|

xxxxxxx |

|

(17) |

|

xxxxxxx |

|

|

|

|||||

DISBURSEMENTS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

DISBURSEMENTS CASH |

xxxxxxx |

|

|

|

xxxxxxx |

|

|

xxxxxxx |

|

1.0 |

|

xxxxxxx |

|

|

|

|||||

|

RETURNS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Form M-RC 8/10 (10/65) Section 7

274-118 |

MRC, Inc. (A) |

5. Project Evaluation Report

On each PAR, the corporate controller indicated whether he desired a Project Evaluation Report (PER). Prepared by the division manager one year after the approved project was completed, this report indicated how well the project was performing in relation to its original cost, return on investment (ROI), and payback estimates.

The PAR System in Action

During 1960, MRC approved 70 PARs calling for the expenditure of more than $17 million. A sample evaluation made in 1961 of some of the projects that the board of directors had approved in earlier years is reproduced as Exhibit A-2.

Exhibit A-2 Summary of Selected Project Evaluation Reports, August 1960

|

|

|

Project Amount |

|

Rate of Return |

|

Payback (years) |

|

|||

Project |

|

Date |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number |

Description |

Approved |

Forecast |

Actual |

|

Forecast |

Actual |

|

Forecast |

Actual |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

FA-157 |

Roll Forming Mill |

1/58 |

S193 |

$193 |

37% |

42% |

2.5 |

2.3 |

|

||

FA-151 |

Universal Paint Machine Unloader |

7/59 |

98 |

43 |

>30 |

>30 |

2.6 |

1.6 |

|

||

FA-147 |

Loading Equipment ‘65 Buick |

7/57 |

80 |

79 |

29 |

29 |

3.1 |

3.3 |

|

||

P 352-51 |

“V” Band Couplings Program |

8/59 |

58 |

90 |

>30 |

Loss |

.7 |

Loss |

|

||

P 328-29 |

New Gas Furnace Line |

6/56 |

295 |

491 |

>50 |

43a |

1.0 |

1.7a |

|

||

P-532 |

Aluminum Die Cast Equipment |

5/59 |

86 |

86 |

>30 |

>30 |

2.2 |

2.0 |

|

||

P-547 |

(2) W-S #1 AC Chuckers |

7/59 |

66 |

66 |

>30 |

>30 |

2.0 |

1.4 |

|

||

64-129C |

(2) W-S Chuckers |

12/58 |

116 |

114 |

12 |

Loss |

5.5 |

Loss |

|

||

a. Estimate.

In discussing capital budgeting at MRC, Archibald Brinton stated that the largest projects, involving more than $1 million, were almost always discussed informally between the president and the division manager at least a year before a formal PAR was submitted. He commented:

Let’s look at a project involving a facilities expansion. The need for a new plant addition in most of our business areas doesn’t sneak up on you. It can be foreseen at least a couple of years in advance. An enormous amount of work is involved in submitting a detailed economic proposal for something like a new plant. Architects have to draft plans, proposed sites have to be outlined, and construction lead times need to be established. No division manager would submit a complete request for a new facilities addition without first getting an informal green light that such a proposal could receive favorable attention. By the time a formal PAR is completed on a large plant addition, most of us are pretty well sold on the project.

Asked what items seemed most significant as he evaluated a newly submitted PAR, Brinton

replied:

The size of the project is probably the first thing that I look at. Obviously, I won’t spend much time on a $15,000 request for a new forklift truck from a division manager with an annual sales volume of $50 million.

I’d next look at the type of project we’re dealing with to get a feel for the degree of certainty in the rate of return calculation. I feel a whole lot more comfortable with a cost reduction project promising a 20% return than I would with a volume expansion project which promises the same rate of return. Cost reduction is

10