INTRODUCTORY-CORRECTIVE COURSE ON ENGLISH PRONUNCIATION

WEEK 1

КОМПЛЕКС БЕЗЗВУЧНИХ ТРЕНУВАЛЬНИХ ВПРАВ

для постановки англійської вимови

1. Оголення зубів (“Оскал”).

Розведіть губи доверху і донизу, дещо оголивши нижні і верхні зуби. Утримуйте губи в натягнутому напруженому положенні, не вип’ячуюючи їх уперед (так званий плоский уклад – flat articulation). Не слід доводити оскал до оголення ясен.

2. Оскал із розкриттям та закриттям рота.

Розімкніть губи, опускайте і піднімайте нижню щелепу при оголених зубах. Губи утримуйте в положенні плоского укладу.

3. Вип’ячування губ.

Інтенсивно, не допускаючи прояву шуму, видувайте повітря з ротової порожнини. При цьому утримуйте губи в напруженому стані.

4. Плоске округлення губ.

Утримуючи губи в положення “оскал”, повільно їх округліть, залишаючи губи притиснутими до зубів (тобто не вип’ячуюючи їх уперед).

5. Опускання й підіймання нижньої губи.

Утримуючи губи в положення “оскал”, злегка підніміть верхню губу, оголивши край верхніх зубів; прикусіть нижню губу верхніми зубами. Опускайте нижню губу, оголюючи нижні зуби. Верхня губа залишається при цьому нерухомою.

6. Висування язика “жалом”.

7. Утримування кінчика язика між різцями зубів. Утримуючи губи в положення “оскал”, висуньте кінчик язика, розташовуючи його між зубами. Губи при цьому залишаються нерухомими.

Key to phonetic symbols

Vowels aпd diphthongs

|

No 1 /i:/ |

as in |

see /i:/ |

No 11 // |

as in |

fur // |

|||

|

No 2 // |

as in |

sit // |

No 12 // |

as in |

ago /'/ |

|||

|

No 3 // |

as in |

ten /tn/ |

No 13 // |

as in |

page // |

|||

|

No 4 // |

as in |

hat /ht/ |

No 14 // |

as in |

home // |

|||

|

No 5 /:/ |

as in |

arm /:/ |

No 15 // |

as in |

five / / |

|||

|

No 6 // |

as in |

got /t/ |

No 16 // |

as in |

now // |

|||

|

No 7 /:/ |

as in |

saw /:/ |

No 17 // |

as in |

join // |

|||

|

No 8 // |

as in |

put // |

No 18 // |

as in |

near // |

|||

|

No 9 // |

as in |

too // |

No 19 // |

as in |

hair // |

|||

|

No 10 // |

as in |

cup // |

No 20 // |

as in |

pure // |

|||

|

Consonants |

||||||||

|

|

as in |

pen // |

|

as in |

so // |

|||

|

|

as in |

bad /d/ |

|

as in |

zoo // |

|||

|

|

as in |

tea // |

|

as in |

she // |

|||

|

|

as in |

did // |

|

as in |

vision // |

|||

|

|

as in |

cat /t/ |

|

as in |

how // |

|||

|

|

as in |

get /t/ |

m |

as in |

man /m/ |

|||

|

|

as in |

chin // |

|

as in |

no // |

|||

|

|

as in |

June // |

|

as in |

sing // |

|||

|

|

as in |

fall // |

|

as in |

leg // |

|||

|

|

as in |

voice // |

|

as in |

red // |

|||

|

|

as in |

thin // |

|

as in |

yes // |

|||

|

|

as in |

then // |

|

as in |

wet // |

|||

|

The Tonetic Stress Marks |

||||||||

|

|

Low |

High |

||||||

|

1. Falling (F) |

\m |

\m |

||||||

|

2. Rising (R) |

/m |

/m |

||||||

|

3. Falling-Rising (Undivided) (F-R) |

m |

m |

||||||

|

Falling-Rising (Divided) (F-R) |

\m ()m /m |

\m ()m /m |

||||||

|

4. Rising-Falling (Undivided) (R-F) |

/\ m |

m |

||||||

|

Rising-Falling (Divided) (R-F) |

/m ()m \m |

/m ()m \m |

||||||

|

5. Rising-Falling-Rising (Undivided) (R-F-R) |

/\/m |

/\/m |

||||||

|

6. Level Tone (L) |

>m |

>m |

||||||

Phonetics / (//)/ is the branch of linguistics which studies the sound means of language from the point of view of their articulation (i.e. the way the speech sounds are produced), acoustic qualities (the way the sounds are transmitted from the speaker’s mouth to the listener’s ear), their function (the way the speech sounds are used in spoken language) and semantics (their role in forming the meaning of larger linguistic units).

Phonetic system of any language consists of two levels: (1) segmental (elementary sounds, vowels and consonants that form the vocalic and consonantal subsystems) and (2) suprasegmental (syllables, accentual (rhythmic) units, intonation groups, utterances, that form the subsystems of pitch, stress, tempo, pauses, etc.). Both levels (so called phonetic level of a language) serve to form and differentiate units of other subsystems of language (lexical and grammatical).

Phoneme is the smallest indivisible language unit, capable of distinguishing one word from another word of the same language or one grammatical form of the same word, and existing in the speech of all the members of a definite language community.

The Phoneme inventory / / of English comprises 20 vowels among which there are 12 monophthongs (,,,,,,,,,,,) and 8 diphthongs (, ,,,,,,). The consonantal system of standard English pronunciation consists of 24 phonemes represented by the following two groups of sounds: noise consonants (, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , ) and sonorants (, , , , , , ). All these sounds have there own frequency of occurrence in the text. Phonemes are elements of the language. Every phoneme is represented in speech by its several variants, or allophones.

Allophones // are speech sounds which are material realizations of one and the same phoneme and which cannot distinguish words or change their meanings, and occur in phonetic contexts different from one another. A phoneme can have an infinite number of allophones. It is important to distinguish between the principal (or typical) variant of a phoneme and its subsidiary variants. They appear in connected speech as a result of assimilation or reduction or due to individual speech habits.

Transcription /(|)|/ is a phonetic alphabet, a system of symbols in which every phoneme is supposed to have its own symbol.

The most fundamental types of transcription are: (1) international; (2) phonemic (or broad) and (3) phonetic (or allophonic, or narrow) transcription.

1) International phonetic transcription, or Alphabet, was introduced by the International Phonetic Association (IPA) in 1887. These symbols, or phonetic alphabet, are provided by the International Phonetic Association and are revised from time to time to implement new discoveries and changes in phonetic theory. International Phonetic Association / (IPA) was founded in France in 1886 by Paul Passy as a forum for teachers who were inspired by using phonetics to improve the teaching of the spoken language to foreign learners and wished to popularize their methods. The Association laid the foundations for the modern science of phonetics. Since its beginning, the Association has taken the responsibility for maintaining a standard set of phonetic symbols to be used in practical phonetics, presented in the form of a chart.

2) In the Phonemic (or broad) transcription every phoneme is given an individual symbol, the number of which is 44 (according to the number of phonemes in British English). In phonemic transcription we use the slant brackets to indicate phonemic symbols, e.g. /pt/, /pt/, /pt/. Note: Phonemic transcription introduces 4 new symbols: // for [], // for [], / for [], /:/ for [:]. This type of transcription is used in studying English as a speciality.

3) Phonetic (or allophonic, or narrow) transcription presents the full range of phonetic symbols which carry a lot of fine detail about the phonetic quality of sounds. In other words, in this type of transcription every allophone has either a special symbol or a diacritic mark, a small mark that can be added to a symbol to modify its value, e.g. a small circle [o] placed under a symbol represents a voiceless sound like // in the word play []; the diacritic mark [ ] beneath a consonant stands for its dental allophone as in eight []. The square brackets [] indicate phonetic (allophonic) symbols. It is used in doing research work in the field of phonetics.

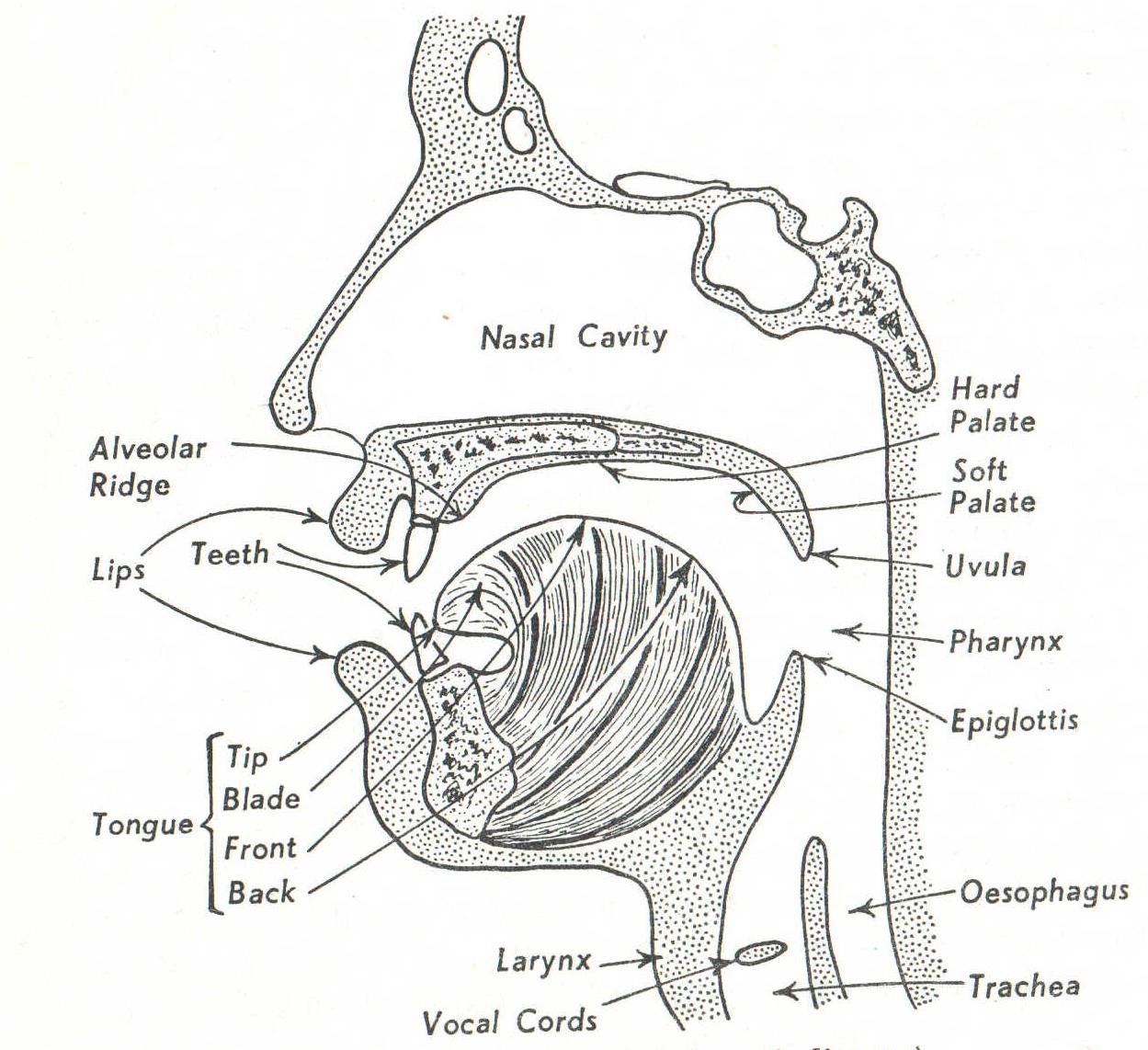

Organs of speech / /, or the vocal organs are a set of organs (lungs, larynx, pharynx, nasal cavity, mouth (or oral) cavity, alveolar ridge, hard palate, velum or soft palate, uvula, vocal cords, tongue, lips, upper and lower jaws, teeth) used for the production of sounds through which people communicate (See Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Organs of speech

There should be distinguished active speech organs, which can be moved into contact with other articulators, such as the tongue, and passive organs of speech, such as the teeth, the hard palate and the alveolar ridge, which are immovable in producing speech sounds.

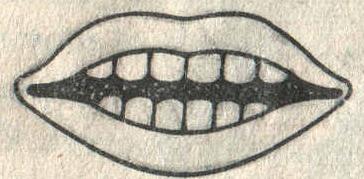

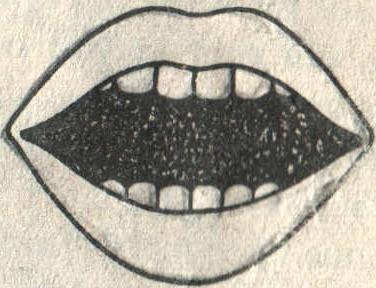

Note!!! The learners have to remember four main lip positions in the production of English sounds:

(a) spread, the most typical lip position in the production of English sounds, e.g.: seed //, meat //, sit //, set //, where lips are slightly spread and pinned to the revealed lower and upper teeth;

(b) neutral (open), i.e. the lips are neither spread nor protruded, though the opening between the teeth is a bit wider than in the spread lip position, e.g.: frog //;

(c) rounded (open) as, for instance, in the production of the phoneme // lips are rounded but they are not protruded, the bulk of the tongue being in its lowest position, e.g.: cat //, sat //, apple //, or the bulk of the tongue is at the back of the mouth cavity as in the production of // though somewhat advanced;

(d) rounded (close), i.e. the lips are rounded but not protruded, e.g.: moon //, look // (see Fig.).

a)

a)  b)

b)

c)

c)

d)

d)

Fig. 2. Four main lip positions in the production of English sounds:

a) spread, b) neutral, c) rounded (open), d) rounded (close)

Articulation basis / / refers to the articulatory habits characteristic of all the native speakers of a language. The peculiarities of the articulation basis of English determine specific articulatory characteristics of its sound system, the character of sound modifications in connected speech and the physiological mechanism of syllable formation.

The main points of difference between the articulation basis of English and Ukrainian are as follows:

1. The tongue in English is more tense and bulky and has a retracted position for most of the phonemes.

2. The lips are also more tense and less movable than in Ukrainian. They are mostly spread (with the lower teeth revealed) or neutral (flat articulation).

3. Forelingual English consonants are articulated with the tongue-tip against the alveoli: /, , , , , , , , , / or against the teeth /, /. The corresponding Ukrainian ones are articulated with the blade of the tongue against the teeth, except for /ш, ж/.

4. All English consonants are hard (except for /, /) and have no palatalized opposition while the Ukrainian ones have. Palatalization in English is a phonetic mistake.

5. The English word-final voiced consonants must not be devocalized, e.g. bag, sad.

6. The English plosive voiceless /, , / are pronounced with aspiration, e.g. Kate, take the plate. The strongest degree of aspiration is registered in these consonants when they occur in word-initial position before a vowel in the production of which the compressed air is prevented from escaping by the articulatory closure, followed by a sound similar to /h/. It is necessary to remember that when voiceless plosives /p, t, k/ are preceded by /s/ at the beginning of a word or syllable they are not aspirated, e.g. speak.

7. The English sonorants /, , / are tenser and longer than corresponding Ukrainian ones, and they are syllabic when post-tonic and preceded by a consonant, thus the words button //, sudden //, cycle // consist of two syllables: / - /, / - /, / - /. Remember, words such as bottle and button would not sound acceptable in RP pronunciation if pronounced //, //.

8. In English, unlike in Ukrainian, vowel sounds differ in length. The duration of a vowel is usually marked by two dots, like in see //. There are five historically long monophthongs in English: /, , , , /. In connected speech they occur in their positional variants: the longest when word final, half long when followed by a voiced consonant and the shortest if it is followed by a voiceless consonant as in – – , respectively.

9. The most frequently occurring vowel of English is schwa //, or the neutral vowel //. It is the most common weak vowel in English which has no regular letter for its spelling and never occurs in a stressed syllable, e.g. in the word about // the first syllable is represented by a schwa vowel. The schwa phoneme occurs in speech in its four allophones:

(1) sound // articulated with the shade of // is pronounced in initial unstressed syllables as in the words anew //, ashore // and in the indefinite article a, e.g.: a book //; this allophone is marked as //, e.g.: aback //, a look //;

(2) when the sound // occurs in a final unstressed syllable it acquires the coloring of the phoneme // and can be marked in allophonic transcription as //, e.g.: other //;

(3) before the suffixes -s, -es, -ed, -er/-or, etc. the schwa vowel // as in the words bettered //, teachers // is characterized by a bit longer duration; this allophone of // is marked with the help of the symbol //, e.g.: classifiers /, delivered //;

(4) the sound // occurs in its shortest in duration when it is used in initial unstressed syllables that have the CVC structure as in contain //, compose // or in the suffixes -tion, -sion and the like as in the words construction, disillusion, function, table; this allophone of the schwa vowel is marked either by the symbol /()/ or as //, e.g.: /()/, //, //, //. Sometimes one can come across several allophones of the // phoneme within one word, e.g.: assumption //, container /()/, etc.