Practical Plastic Surgery

.pdf

122 Practical Plastic Surgery

Table 23.1. Terminology of various skin lesions and disorders

Term |

Definition |

Size |

Papule |

A palpable elevated skin lesion |

< 1 cm |

Plaque |

A larger palpable elevated skin lesion |

> 1 cm |

Macule |

A flat, colored, nonpalpable lesion |

< 1 cm |

Patch |

A larger flat, colored, nonpalpable lesion |

> 1 cm |

Vesicle |

A fluid-filled blister |

< 0.5 cm |

Bulla |

A larger fluid-filled blister |

> 0.5 cm |

Hyperkeratosis |

Increased thickness of the stratum corneum |

variable |

Parakeratosis |

Hyperkeratosis with retained keratinocyte nuclei |

variable |

Acanthosis |

Thickening of the epidermis |

variable |

Hypertrophic scar |

Raised scar that is confined to the borders |

variable |

|

of the wound or incision |

|

Keloid |

Raised scar that extends beyond the borders |

variable |

|

of the wound or incision |

|

lipid rich material and have a tendency to become infected. Treatment consists of excision during which the entire lining must be removed to avoid recurrence. Mildly infected cysts should be treated with antibiotics for one week prior to excision. Severely infected cysts should undergo incision and drainage.

The pilar cyst, or trichilemmal cyst, is the epidermoid cyst equivalent on the scalp. Multiple epidermoid cysts can be seen in Gardner’s syndrome (familial polyposis).

Moles

The nevocellular nevus (common mole) is a benign congenital lesion derived from the melanocyte that occurs in clusters or nests. The junctional nevus, commonly seen in children and younger adults, consists of cells confined to the

23epidermal-dermal junction. It is a smooth and flat nevus with irregular pigmentation. The compound nevus has cells in both the epidermal-dermal junction and the dermis. It is usually raised and represents a progression from the junctional nevus. The intradermal nevus contains cells in clusters that are confined to the dermis.

The Juvenile melanoma (Spitz nevus). usually occurs in children as a pale red papule on the face. Despite its name, it is a benign lesion. It is treated by excision with margins due to the risk of recurrence.

The atypical mole, formery referred to as dysplastic nevus, is premalignant. It is unevenly pigmented and has irregular borders. The lesion is usually solitary and is clinically indistinguishable from melanoma. Atypical moles should be biopsied. The familial form, B-K mole syndrome, presents with hundreds of atypical moles and confers a 100% risk of malignant transformation. Patients must have an annual photographic examination of their entire bodies. Any lesions that change must be excised.

The nevus of Ota is benign blue-grey macule that is found on the face in the V1 or V2 distribution of the trigeminal nerve. It is usually congenital and has a female predisposition. It is treated with laser therapy.

Benign Skin Lesions |

123 |

The blue nevus is similar to an intradermal nevus in that it is composed of intradermal melanocytes. It presents as a well-defined papule that can be distinguished from venous lesions by the fact that it does not blanch. Distinguishing it from Kaposi’s sarcoma or melanoma can be difficult. It has a very small risk of malignant degeneration. It is treated by excision.

The freckle is a pigmented lesion that represents excessive melanin granule production without an increase in the number of melanocytes. Freckles are benign and have no malignant potential.

Lesions of the Epidermal Appendages

This group of miscellaneous benign lesions includes those derived from hair follicles and sebaceous, apocrine and eccrine glands. Most of the lesions requiring treatment occur in the scalp and face. They are summarized in Table 23.2.

Lesions of the Dermis and Subcutaneous Fat

A number of benign tumors occur in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Their behavior may range from completely benign to recurrent and locally aggressive.

Lipomas are fatty tumors of the subcutaneous fat. They are soft, mobile and usually painless. They can range in size from one to tens of centimeters. Larger lipomas are more likely to recur; they are often classified as low-grade liposarcomas. Small lipomas do not need to be biopsied. Patients with very large lipomas should undergo MRI to determine whether local invasion has occurred. Treatment consists of total excision as lipomas may recur if not completely removed.

Dermatofibromas are encapsulated intradermal masses that are painless, firm and mobile. They usually are less than 2 cm and occur on the extremities. Due to their accumulation of hemosiderin, they can display the range of colors seen in an evolving bruise. Treatment consists of excision, mostly for cosmetic purposes. They may recur if incompletely excised.

The dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a locally aggressive, indolent, nodular intradermal mass. It occurs on the trunk and thighs. They are often painful and

can be complicated by ulceration or superinfection. The overlying epidermis may 23 appear waxy. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans tends to grow extensions into the surrounding dermis and fascia, creating a gross “cartwheel” appearance. Treatment consists of wide excision to encompass the extensions of the tumor. Metastasis has

been described in neglected or incompletely excised lesions.

Angiofibromas present as small, erythematous, telangiectatic papules, usually located on the cheeks, nose or around the lips. They are benign when solitary. Superficial excision is the standard treatment. When multiple, these papules may be associated with tuberous sclerosis (seizures, mental retardation, renal angiomyolipoma). Dermabrasion can offer some cosmetic improvement for patients with multiple angiofibromas.

Skin tags, also termed cutaneous papillomas, are soft and often pedunculated, arising from a central stalk. They may become infected or may necrose. Treatment consists of amputation at the stalk and electrodissection of the remaining base. They are benign and do not recur.

Glomus tumors present as a painful, firm, blue nodules on the hands and feet, especially subungually. They are benign vascular hamartomas derived from the glomus body. Excision is often required due to the pain caused by pressure from these tumors.

124

23

Table 23.2. Lesions of the epidermal appendages

Table 23.2. Lesions of the epidermal appendages

Practical Plastic Surgery

Treatment |

Excision |

Excision |

Laser,cauteryorcryotherapy |

Excision |

Excision |

Excision |

Excision |

Laser,cauteryorcryotherapy |

Excision |

Excision |

Excision |

Location |

Face |

Face |

Periocular |

Foot |

Scalp,forehead |

Forehead |

Head,neck |

Face |

Face,neck,arms |

Face |

Face,scalp |

ClinicalAppearance |

Translucentdomeshapedpapule |

Firm,fixedpainlessnodule |

Clearpapuleoccuringinadults |

Softrednoduleatanyage |

Smoothpinkpapuleorplaque |

Linearyellowishplaque,onsetatbirth |

Yellownoduleinadults |

Ulceratedyellow-whitepapules |

Firmnodulestretchingtheskin |

Pink,shinypapulesoraplaque |

Skincoloredpapulewithcentralhair |

TissueofOrigin |

Apocrinegland |

Apocrinegland |

Eccrinegland |

Eccrinegland |

Eccrinegland |

Sebaceousgland |

Sebaceousgland |

Sebaceousgland |

Hairfollicle |

Hairfollicle |

Hairfollicle |

Lesion |

Apocrinecystadenoma |

Chondroidsyringoma |

Syringoma |

Eccrineporoma |

Cylindroma |

Nevussebaceus |

Sebaceousadenoma |

Sebaceoushyperplasia |

Pilomatricoma |

Trichoepithelioma |

Trichofolliculoma |

Benign Skin Lesions |

125 |

Pearls and Pitfalls

Although most of the lesions described in this chapter are benign, many are difficult to clinically distinguish from malignant tumors of the skin. Furthermore, some of the lesions, such as atypical moles, may remain unchanged for years before undergoing dysplastic changes. Even the most experienced surgeon has been fooled on occasion by a lesion he was sure could not be malignant. These facts emphasize the importance of excisional biopsy of any suspicious skin lesion. Skin incisions should adhere to the principles of relaxed skin tension lines in the neck and face, and should be longitudinal in the extremities. The excision should be as complete as possible; any part of the lesion that appears to have been left behind should also be excised. All excisional biopsies should be sent to a pathologist. When applicable, specimens should be oriented with a marking stitch. Finally, it is the obligation of the surgeon to follow up on the pathology report and notify the patient of the results.

Suggested Reading

1.Demis DJ, ed. Clinical Dermatology. 22nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1995.

2.Kumer et al, eds. Robbins Basic Pathology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997.

3.Zarem HA, Lowe NJ. Benign growths and generalized skin disorders. In: Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997:141.

4.Slade J et al. Atypical mole syndrome: Risk factors for cutaneous malignant melanoma and implications for management. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995; 32:479.

23

Chapter 24

Basal Cell and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Darrin M. Hubert and Benjamin Chang

Overview

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) comprise the vast majority of nonmelanoma skin cancers. Over one million white Americans are affected by these two entities yearly. They predominantly affect fair-skinned individuals, and their incidence is rising rapidly. Etiology may be multifactorial, but sun exposure appears to play a critical role. When detected early, their prognosis is generally excellent. However, both are malignant cutaneous lesions with inherent metastatic potential. Thus appropriate diagnosis, treatment and surveillance are of utmost importance. Malignant melanoma was discussed in the previous chapter.

Premalignant Lesions

The most common precursor of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma is the actinic keratosis, also known as the solar keratosis. It appears as a scaly, discrete, maculopapular lesion that arises primarily on sun-damaged skin. Palpation of these flat lesions may reveal roughness that is not apparent on visual inspection. Due to the potential for progression to SCC, actinic keratoses are commonly treated by curettage and electrodessication, liquid nitrogen or topical 5-FU (Efudex).

Bowen’s disease is a type of squamous cell carcinoma-in-situ marked by a solitary, sharply demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaque of the skin or mucous membranes. A second form of squamous cell carcinoma-in-situ is erythroplasia of Queyrat, which appears as glistening red plaques on the uncircumcised penis. Both have the potential for progression to invasive carcinoma and should be resected completely with conservative surgery.

Leukoplakia is a condition found on the oral mucosa commonly in association with smokeless tobacco use. These white patches may undergo malignant transformation to SCC in 15% to 20% of cases if left untreated. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis is a rare autosomal recessive disorder in which the body is unable to control human papilloma viral infections. It manifests itself as flat wart-like lesions that frequently degenerate into SCC. A keratoacanthoma, on the other hand, grows rapidly to form a nodular, elevated lesion with a hyperkeratotic core. It may involute spontaneously or appear indistinguishable from a SCC, and early conservative excision is recommended.

Tumor Staging

All nonmelanoma skin cancers are staged by the TNM system established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). The staging system is shown in Table 24.1. Characteristics of the primary tumor (T), regional lymph node status

(N) and distant metastasis (M) are considered. BCC rarely metastasizes, although it may be locally destructive. The malignant potential of SCC is real and is related to the size and location of the tumor, as well as the degree of anaplasia.

Practical Plastic Surgery, edited by Zol B. Kryger and Mark Sisco. ©2007 Landes Bioscience.

Basal Cell and Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

127 |

|

|

|

|

Table 24.1. Staging of nonmelanoma skin cancers according to the TNM system established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)

Primary Tumor (T)

TX Primary tumor cannot be assessed T0 No evidence of primary tumor Tis Carcinoma in situ

T1 Tumor 2 cm or less in greatest dimension

T2 Tumor more than 2 cm, but not more than 5 cm in greatest dimension T3 Tumor more than 5 cm in greatest dimension

T4 Tumor invades deep extradermal structures (e.g., cartilage, muscle or bone)

Regional Lymph Nodes (N)

NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed N0 No regional lymph node metastasis

N1 Regional lymph node metastasis

Distant Metastasis (M)

MX Distant metastasis cannot be assessed M0 No distant metastasis

M1 Distant metastasis

Staging System |

|

|

|

Stage 0 |

Tis |

N0 |

M0 |

Stage I |

T1 |

N0 |

M0 |

Stage II |

T2 |

N0 |

M0 |

Stage III |

T3 |

N0 |

M0 |

T4 |

N0 |

M0 |

|

Stage IV |

Any T |

N1 |

M0 |

Any T |

Any N |

M1 |

Basal Cell Carcinoma

BCC is the most common skin cancer and, indeed, the most common malignancy

in the United States and Australia. It outnumbers cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma 24 by approximately four to one. Its origin lies in the basal layer of the epithelium or the external root sheath of the hair follicle. Classic teaching holds that BCC requires stro-

mal participation for survival, not the malignant transformation of preexisting mature epithelial structures seen in SCC. Although its metastatic potential is very low, basal cell carcinomas exhibit oncogene and tumor suppressor gene characteristics that question this classic explanation. Basal cell carcinoma tends to follow the path of least resistance, spreading into adjacent tissues. It only rarely metastasizes to distant sites.

Classification

Multiple histologic classifications have been proposed for subtypes of BCC, however, only the most common are mentioned here. Nodular BCC is the most common (45-60%), found typically as single translucent papules on the face. It is firm, may ulcerate, and often exhibits telangiectasia. Superficial BCC (15-35%) occurs as multiple scaly lesions on the trunk. Lightly pigmented or erythematous, it may resemble psoriasis or eczema. The less common subtypes are usually more aggressive. These include infiltrative BCC (10-20%), morpheic BCC (9%), which is associated with the highest recurrence rate, micronodular BCC (15%) and adenoid BCC (precise incidence unknown).

128 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

Risk Factors

Exposure to ultraviolet radiation appears to play a major role in the development of BCC. A thorough history during the preoperative evaluation should investigate this, making special mention of any significant sunburns during childhood or adolescence. Other risk factors include exposure to radiation or chemical carcinogens such as arsenic, Fitzpatrick skin type 1 or 2 (fair skin), increasing age, male sex, xeroderma pigmentosum, albinism and immunosuppression. Patients with basal cell nevus syndrome may develop multiple basal cell carcinomas. This syndrome, known eponymously as Goltz-Gorlin syndrome, is characterized by odontogenic keratocysts, palmar or plantar pits, cleft lip or palate, rib anomalies and areas of ectopic calcification. Nevus sebaceous lesions also predispose to BCC. As hairless yellow plaques present at birth, these lesions are typically found in the head and neck region. They may undergo malignant transformation in 10% of cases.

Special mention should be made of the importance of the “H-zone” of the face. This designation, roughly in the shape of an “H,” is defined by the preauricular regions and ear helices, nasolabial folds, columella and nose and lower eyelids. BCC lesions located in this area are associated with both a higher risk of recurrence and greater morbidity as a consequence of treatment.

Treatment

There are several modalities available for the treatment of BCC. For a given lesion, one must weigh the treatment in terms of effectiveness in eliminating the malignancy against the functional and cosmetic implications before choosing the appropriate route.

First, surgical excision involves the full-thickness removal of the lesion, down to subcutaneous fat, along with a rim of “normal” tissue. Current literature recommends margins of 3 mm for small (<10 mm) and 5 mm for larger (10-20 mm) BCC of the face. For lesions found in any other location, margins of 5 mm are recommended. These wounds are typically either closed primarily or allowed to heal by secondary intention. For lesions located in delicate areas of the face, such as the eyelids, where removal of a margin of normal tissue may have profound functional consequences, Mohs micrographic surgery may be indicated. This technique has demonstrated the highest cure rates of any treatment modality. Cure rates of 99%

24for primary BCC and 93-98% for recurrent BCC have been demonstrated with the use of Mohs surgery. The technique of Mohs surgery is discussed in detail below.

An additional accepted treatment is cryotherapy, which is typically followed by curettage and healing by secondary intention. Local anesthesia is used, and the lesion is rapidly frozen with liquid nitrogen. There is no histological control with this method, and the tissue typically becomes initially very edematous. Its use has been advocated particularly near underlying cartilage. Recurrence rates of 3.7-7.5% have been reported.

Curettage and electrodessication have been employed in the past, with recurrence rates of 3.3% for low risk lesions to 18.8% for high risk ones. Due to unacceptably high recurrence rates, poor cosmetic outcome and lack of histological control, it is generally not accepted as a first line therapy for BCC. Radiation therapy has also been used to treat BCC, but the risk of radiation dermatitis, increased risk for future skin malignancy, and lack of histological control have discouraged its current use.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Risk Factors

Similar to BCC, cutaneous SCC typically occurs in areas of skin receiving the greatest sun exposure. The etiology appears to be the result of UVB radiation

Basal Cell and Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

129 |

(wavelength range of 290-320 nm), which produces thymidine dimers in the DNA of the p53 tumor-suppressor gene. Fair-skinned individuals, albinos and those with xeroderma pigmentosum seem to be at particularly increased risk. Other risk factors include infection with human papillomavirus, chronic immunosuppression such as that seen in the organ-transplant population, exposure to chemical carcinogens such as arsenic, and exposure to ionizing radiation. Chronically inflamed or damaged skin may predispose to carcinoma as well, termed Marjolin’s ulcer. These are most commonly squamous cell carcinomas, and they can arise in long-standing, chronic wounds such as pressure sores, fistulae, venous ulcers, lymphedema and burn scars.

Recurrence and Metastasis

The metastatic potential of SCC is greater than that of BCC, and the relative risk of recurrence and metastasis can be assessed according to characteristics of the lesion. The most important predictor is size of the tumor, with lesions greater than 2 cm in diameter recurring at a rate of 15% and resulting in metastasis at a rate of 30%. Anatomic location predicts greater malignant potential, especially the lip and ear, but also the scalp, forehead, eyelid, nose, dorsum of the hands, penis and perineum. Other features associated with higher risk of recurrence and metastases are rapid tumor growth, host immunosuppression, prior local recurrence, depth of invasion greater than 4 mm or into the subcutaneous tissues and location in a Marjolin’s ulcer. Perineural invasion denotes a particularly poor prognosis and is lethal in a majority of patients by five years.

Treatment

With the exception of cryotherapy, treatment options for SCC are similar to those for BCC. However, there have been no randomized controlled trials comparing the efficacy of the various techniques. Direct surgical excision has demonstrated a recurrence rate of approximately 8% and metastatic rate of 5% at five years. Some authors have advocated surgical margins of 4 mm for low risk lesions and 6 mm for high-risk lesions whenever feasible. Mohs surgery has demonstrated the highest cure rates, about 97% for primary SCC, and is especially recommended for high-risk

lesions. Due to lack of histological control and unacceptable cure rates, curettage 24 with cautery, cryosurgery and radiotherapy are not recommended.

Mohs Surgery

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) was developed by Dr. Frederic Mohs in the 1930s. Dermatologists with specialized fellowship training in Mohs surgery typically perform the technique today. Fresh-tissue horizontal frozen sections are the hallmark of the procedure. Another salient feature is that the surgeon who performs the excision also interprets the histological results. The process can be summarized briefly in the following steps:

1.Gross debulking of the tumor

2.Excision of a narrow (2-3 mm rim) of normal tissue, beveled at 45˚ at the edges

3.Color-coding of specimen to mark margins and orientation

4.Mapping of the specimen and division into sections

5.Frozen-section processing in on-site laboratory

6.Microscopic examination

7.Repeat cycle if any residual tumor is noted

8.Healing by secondary intention, primary closure, skin graft or flap closure

130 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

This approach combines the highest cure rates for nonmelanoma skin cancer with maximum preservation of normal tissue and function. It provides the theoretical benefit of being able to examine 100% of the surgical margin in a single sitting, compared to the standard “bread-loafing” histological examination of surgical specimens. The disadvantages are that is can be time-consuming, labor intensive and expensive. Indications for Mohs micrographic surgery over other treatments include location of the lesion in the “H-zone,” tumors greater than 2 cm in diameter, aggressive tumors, recurrent tumors, tumors in previously irradiated areas, incompletely excised tumors, clinically ill-defined tumors, presence of perineural invasion and aggressive rare tumors such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, microcystic adnexal carcinoma or sebaceous gland carcinoma.

Follow-Up Examinations

Follow-up after treatment of skin cancers consists of monthly whole-body skin self-examinations and twice yearly skin examinations by a dermatologist or other qualified medical provider for at least five years to check for local recurrence as well as the occurrence of a second primary. Patients with larger SCC should be examined every three months, including palpation of regional lymph nodes, for several years and then followed at six-month intervals for the rest of their lives.

Pearls and Pitfalls

The two main pitfalls in treating skin cancers are missed or delayed diagnosis and inadequate biopsy. Although some skin cancers can be diagnosed by visual inspection alone, histologic confirmation is essential. The adage “when in doubt, cut it out” should be applied when dealing with skin lesions. A corollary to that rule is “if the patient wants it out, cut it out.” If one fails to biopsy a lesion, which later turns out to be a malignancy, the delay in treatment can lead to a higher risk of recurrence, metastases and malpractice suits. An excisional biopsy is preferable because it gives the pathologist the entire lesion to examine. If the lesion is large, a representative incisional or punch biopsy, taking the full thickness of the skin, is preferable to a shave biopsy, particularly if the lesion turns out to be a melanoma.

As in other areas of tumor surgery, reconstructive concerns should not compromise surgical margins. One way to avoid this “conflict of interest” is to have one sur-

24geon excise the lesion and another reconstruct the defect. Mohs surgery is particularly well suited to this two-surgeon approach. For extensive tumors treated by standard excision, delayed reconstruction should be considered in order to wait for the final histological margins, unless the defect can be closed primarily. One should not proceed with a complex flap reconstruction solely on the basis of an intraoperative frozen section examination of the margin because of the potential for a false negative.

Suggested Reading

1.Greene FL et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Raven Publishers, 2002:203.

2.Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2001; 344(13):975.

3.Kuijpers DI, Thissen MR, Neumann MH. Basal cell carcinoma, treatment options and prognosis, a scientific approach to a common malignancy. Am J Clin Dermatol 2002; 3(4):247.

4.Motley R, Kersey P, Lawrence C. Multiprofessional guidelines for the management of the patient with primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg 2003; 56:85.

5.Nelson BR, Railan D, Cohen S. Mohs’ micrographic surgery for nonmelanoma skin cancers. Clinics Plast Surg 1997; 24(4):705.

6.Snow SN, Madjar Jr DD. Mohs surgery in the management of cutaneous malignancies. Clinics Derm 2001; 19(3):339.

Chapter 25

Melanoma

Gil S. Kryger and David Bentrem

Introduction

Malignant melanoma is the leading cause of death from skin cancer, despite only accounting for a fraction of all cutaneous cancers. The incidence of melanoma has doubled over the past 35 years in the United States. In 2002, there were 53,000 new cases in the U.S. The mean age of diagnosis was 45 years and the lifetime risk (in the U.S.) is 1 in 58 for men and 1 in 82 for women. The lowest rates occur in China and Japan (0.3/100,000) and the highest rates are in Australia and New Zealand (36/100,000).

In addition to geographic risk factors, there are several patient-related factors that are associated with an increased incidence of disease. Individuals with fair skin have a higher risk of developing melanoma. The incidence is 10 times higher in whites than blacks. People with red hair have a 3.6 times higher incidence of melanoma than those with black hair. Other risk factors include a history of severe sunburns in childhood, freckling after sun exposure, and people with more than 20 nevi on their body. Of patients with melanoma, 5-11% will have a family member with melanoma.

Classification

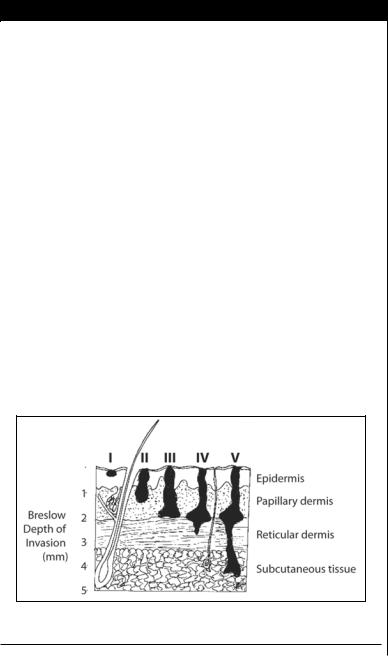

Histologic level of invasion (Clark’s level) and tumor thickness (Breslow thickness or depth) are important indicators of metastatic risk and outcome (Fig. 25.1). Lymph node status is the single most powerful predictor of survival. When lymph nodes are not involved, the most important factors for prognosis are Breslow depth

Figure 25.1. A schematic diagram of Breslow depth and Clark’s levels of invasion.

Practical Plastic Surgery, edited by Zol B. Kryger and Mark Sisco. ©2007 Landes Bioscience.