Practical Plastic Surgery

.pdf

102 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

However, albumin has a very short half life and is not a precise reflection of nutritional status. Serum prealbumin and transferrin levels are more accurate. Patients unable to obtain adequate caloric intake on their own should receive supplemental enteral feeding with TPN being a second choice. In addition to adequate protein levels, wound healing requires zinc, vitamin C, and other vitamins and minerals. Nutritionally depleted patients should receive a daily multivitamin.

Comorbid Conditions

A number of medical conditions, if not treated, will have a detrimental effect on the healing of any surgical flap. Diabetes must be managed aggressively, and blood sugars should be kept below 150. It is well known that uncontrolled blood sugars have a significant negative impact on healing tissue.

Active infections such as urinary tract or pulmonary infections must be completely treated prior to surgery. It is ill advised to operate on an actively infected patient. Any individual with bacteremia should demonstrate a negative blood culture prior to surgery.

For patients with severe peripheral vascular disease, a preoperative angiogram or magnetic resonance angiography should be considered. Since a number of flaps survive based on blood supply from the internal iliac vessels, it is important to rule out significant disease of these vessels. If indicated, a vascular bypass or stent/angioplasty should precede flap surgery.

Psychiatric conditions, especially depression, should be addressed. These are common in many pressure sore patients, especially the elderly. Since patient compliance is essential to the successful healing of a pressure ulcer, it is vital to ensure that a psychiatric evaluation be performed when appropriate. In addition, patients who

19abuse alcohol or illicit drugs should undergo drug rehabilitation prior to surgery. There is a very high risk of pressure sore recurrence among illicit drug users with spinal cord injuries.

Finally, patients taking steroids should receive vitamin A, (10,000 IU daily) to counteract the detrimental effects of steroids on the wound healing process. Vitamin A may stimulate macrophages that have been inhibited by the steroids. Furthermore, some evidence shows that vitamin A reverses the inhibitory effects that steroids have on TGF-beta.

Nonsurgical Management

Pressure Sore Staging System

It is useful to classify pressure sores according to the depth of the ulcer. There are several classification schemes of pressure ulcers that are commonly used. The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel uses a four stage system. The following staging system is used at our institution and is based on Shea’s modification of this system:

Stage I |

— intact skin with nonblanchable erythema |

Stage II |

— ulceration through the epidermis and most of the dermis |

Stage III |

— ulceration through the dermis into deeper subcutaneous tissue |

Stage IV |

— ulceration down to underlying bone |

Stage V |

— closed large cavities with a small sinus opening |

This staging scheme is useful for treatment purposes since most pressure sores which are either stage I or II usually can be healed with nonsurgical, conservative treatment. Stage III and IV ulcers will often require surgical intervention to heal.

Pressure Ulcers |

103 |

Stage IV ulcers should be evaluated for osteomyelitis as described above. It is important to note that most stage III pressure ulcers may have a component of stage IV, i.e., ulceration down to bone. Stage V ulcers should be unrooted.

Pressure Relieving Strategies

Aside from adequate wound care, relieving pressure is the most important measure to stop the progression of a pressure ulcer and to allow healing to begin. Frequent turning (every 1-2 hours) is mandatory. If possible, the patient should perform this himself. If not, it is imperative that the care-givers be instructed on the importance of this.

A number of hospital beds have been designed to relieve pressure on any one point of the body below 30 mm Hg. Low-air-loss beds or air-fluidized beds are the most common beds used. These are partially effective in reducing pressure on the ulcer, but they are not substitutes for frequent turning. For heel ulcers, there are a number of boots designed to relieve pressure on the calcaneus. Patients confined to wheelchairs can use cushions or foam padding under pressure points (i.e., the ischial tuberosities).

Dressings and Debriding Agents

Simple gauze dressings have withstood the test of time as a first-line treatment of pressure ulcers. They are the cheapest, least invasive means of treating pressure sores, and their use requires minimal training. Gauze dressings should only be applied to ulcers after manual debridement of any thick, superficial eschar. Dressings can be used both as a moist barrier to facilitate wound granulation, and as a method of mechanical debridement.

For superficial stage I ulcers, keeping the sore moist and clean is sufficient. This

can be achieved with a transparent thin film adherent dressing such as a Tegaderm 19 or Opsite. These will heal quickly as long as external pressure is relieved. For stage II ulcers, a moist dressing should be applied. It should not be allowed to dry out. This

can be achieved by saturating gauze with normal saline and changing it before it has dried (wet-to-moist dressing). Another method is to coat the gauze with a water based gel such as Hydrogel or Aquaphor. Alternatively, gauze impregnated with a petroleum-based substance (Vaseline gauze, Xeroform, Xeroflow) will also prevent the ulcer from drying out.

Stage III and IV ulcers usually require some amount of mechanical debridement. The classic wet-to-dry dressing can achieve this by drying out within the ulcer and in the process sticking to any necrotic cellular debris. This dressing should be changed 3-4 times a day. Once the ulcer demonstrates pink, healthy granulation tissue, a switch should be made to a continuously moist dressing. Grossly contaminated, foul smelling ulcers can be treated with a modified wet-to-dry dressing using 0.25% Dakins bleach instead of saline. Dakins dressings should not be used for extended periods of time because they cause wound desiccation. It is important to emphasize to anyone involved in dressing changes not to pack large ulcers with individual, smaller pads of gauze (i.e., 2 x 2 or 4 x 4 gauze), but rather to use one continuous long piece of gauze (e.g., Kerlix gauze). There have been many cases of gauze pads being unintentionally left in ulcers for weeks.

An alternative form of debridement is with the use of enzymatic debriding agents. Most of these contain a papain derivative (an enzyme found in papaya) that enzymatically digests necrotic tissue. Common agents include Accuzyme® and Panafil®. Another commonly used substance is collagenase. They are applied 1-2 times a day directly onto the ulcer and covered by dry gauze. The efficacy of these agents is

104 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

limited; they cannot be expected to debride a grossly contaminated wound or a thick, tough eschar. Both dressings and debriding agents are discussed in greater detail in Section 1 of this book.

Many pressure ulcers will heal with time by secondary intention as long as there is not excessive pressure, no underlying infection and adequate wound care is performed. For large ulcers this can take weeks to months, and therefore flap closure should be considered for all large stage III and IV pressure sores.

Negative Pressure Therapy (wound VAC)

Vacuum-assisted closure has become the nonsurgical method of choice for treating stage III and IV pressure ulcers at many centers. Studies have demonstrated that smallto moderate-sized pressure ulcers being treated with VAC therapy heal faster and with fewer complications than with conventional dressing changes alone. The VAC is also an excellent temporizing measure to help prepare the ulcer for flap coverage. Surgical debridement should be performed prior to initiation of the VAC. The wound VAC is described in detail in the first section of this book.

Hydrotherapy

Also termed whirlpool, hydrotherapy is sometimes used for mechanical debridement of pressure ulcers, especially those on the lower extremities. It’s more common use is for venous stasis ulcers. There are no randomized prospective trials that demonstrate the efficacy of hydrotherapy. Benefits of this modality include less pain than many other forms of treatment for sensate patients, easier removal of dressings stuck to the wound, and high patient satisfaction. Pulsed lavage has largely replaced whirlpool as the preferred hydrotherapy treatment for pressure sores. Studies have

19shown it to increase the rate of granulation tissue formation compared to whirlpool. Its primary use is to decrease bacterial count in the ulcer. Optimal lavage pressures are in the range of 10-15 psi. Local wound care and dressing changes should be performed between hydrotherapy treatments.

Surgical Management

Debridement

Surgical debridement is required for all necrotic ulcers, in which case, the reconstructive procedure should be delayed until the ulcer is clean and granulating. Some surgeons, however, will perform both the debridement and coverage as a single-stage procedure. Debridement can be performed at the bedside or in the operating room. Most denervated patients will tolerate bedside debridement; however only superficial debridement of necrotic tissue should be done at the bedside. Patients with coagulopathies or those with severe thrombocytopenia should be debrided in the operating room. Operative debridement should include all necrotic soft tissue. This will speed up the granulation process, as well as decrease the bacterial load in the ulcer. Bone should be debrided conservatively, especially in the ischial region. Total ischiectomy should be reserved for cases in which there is extensive destruction of the ischium due to the high rate of complications from this procedure. Bone specimens should be sent for pathology and culture to rule out osteomyelitis. Tissue may be sent for culture; however it will usually be colonized with polymicrobial flora. Diagnosing soft tissue infection is therefore determined clinically rather than by the microbiology laboratory.

Pressure Ulcers |

105 |

Femoral Head Excision (Girdlestone arthroplasty) |

|

Excision of the femoral head is appropriate in the permanently nonambulatory |

|

patient when there is evidence of extension of a pressure ulcer (usually trochanteric |

|

or ischial) into the femoral joint space. This diagnosis can be made clinically. The |

|

patients usually presents febrile, with a septic picture. There is communication of |

|

the joint space with the ulcer, and this can be demonstrated with a cotton-tip appli- |

|

cator. Femoral head excision can be performed as part of the debridement procedure |

|

or in a single stage along with the flap coverage. When a Girdlestone arthroplasty is |

|

performed, the resulting dead space must be obliterated with a bulky, muscle or |

|

musculocutaneous flap. |

|

Flap Selection |

|

Flap selection is based on the location of the pressure sore, the local tissue that is |

|

available, and whether muscle is required in addition to subcutaneous fat and fascia. |

|

As a general guideline, large dead-spaces should be filled with muscle. In addition, |

|

ulcers with infected bone or those that are at a high risk of reinfection, should be |

|

covered by a muscle flap. There is no overriding rule that dictates whether an ulcer |

|

should be covered with a fasciocutaneous perforator flap or a myocutaneous flap. |

|

This is based largely on surgeon preference. There are studies that strongly advocate |

|

each type of flap as a first-line choice. Another consideration in patients with distal |

|

spinal cord injuries is whether to use a sensory flap. This involves using sensate |

|

tissue from above the level of injury to cover the ulcer in hopes that sensation will |

|

result in behavior modification by the patient to avoid pressure on ulcer-prone areas |

|

and prevent recurrent ulceration. |

|

The following flaps are commonly used for pressure ulcer reconstruction: |

19 |

• For ischial pressure ulcers, gluteal perforator flap or posterior thigh flaps |

•For sacral pressure ulcers, the V-Y advancement type gluteal flaps

•For trochanteric pressure ulcers, the TFL or posterior thigh flaps

Prior to elevation of the flap, the pressure ulcer should be prepared by excising

any nonhealthy tissue, removing the pseudobursa and smoothing out the underlying bone. The skin edges should be trimmed back until healthy bleeding is seen. Attention is then turned to the flap. After marking the skin paddle, the site of the main pedicle or perforating vessels should be located with a hand-held Doppler.

An outline of the more commonly used flaps for pressure ulcer repair is listed below:

Gluteal Perforator Flap

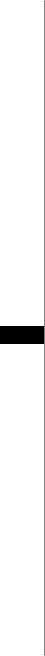

A fasciocutaneous flap based on perforators from the gluteal vessels. It is commonly used for sacral ulcers (Fig. 19.1) but can also be used for ischial and trochanteric defects.

1.The skin paddle is marked: either a transposition or V-Y advancement pattern is used, keeping in mind the ability to close the donor site directly.

2.The distal skin is incised, down to the gluteal muscles.

3.The flap is elevated along with the muscle fascia. Care is taken to locate the perforators.

4.The proximal perforators to be saved are skeletonized to allow greater flap mobility. Those that hinder flap mobility are ligated and divided.

5.Once the perforators are isolated, the proximal skin is incised, creating an island flap.

106 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 19.1. The superior gluteal artery perforator (SGAP) flap for coverage of a sacral wound.

6.The flap is transposed or advanced into the defect and sewn into place with two layers.

7.The donor site is closed directly over a suction drain, and an additional drain is placed under the flap.

Gluteus Myocutaneous Flap

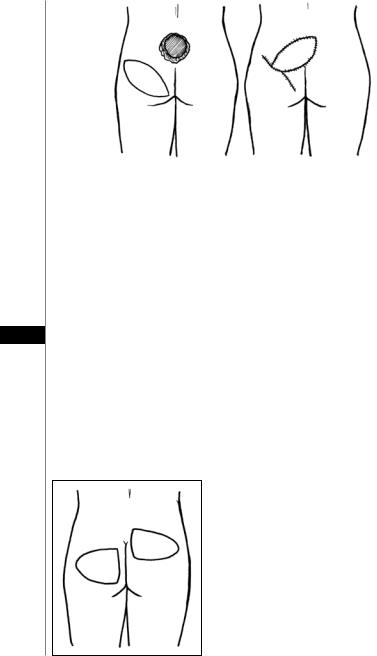

A Type III myocutaneous flap based on either the inferior or superior gluteal artery or both. It is a versatile flap commonly used for both ischial and sacral pressure sores. Bilateral flaps can be advanced medially to close a large midline sacral defect.

191. Either a superior or inferior skin paddle can be utilized (Fig. 19.2). The superior skin paddle is based on the superior gluteal artery and the inferior paddles on the inferior gluteal artery (The entire muscle and buttock skin can be based on the inferior artery).

2.The muscle flap can be advanced or rotated (see Fig. 19.1).

3.The skin and subcutaneous tissue are divided. For rotational flaps, the muscle insertion (greater trochanter and IT band) is also divided.

4.The inferior and lateral borders of the muscle are divided. The muscle is detached from its origin. For ambulatory patients, the inferior portion of the muscle with its insertion and origin should be preserved.

Figure 19.2. The gluteus myocutaneous flap. Examples of a superior and inferior skin paddle.

Pressure Ulcers |

107 |

5.The pedicle and the sciatic nerve are located using the piriformis muscle as a landmark (the sciatic nerve emerges from beneath this muscle).

6.The flap is inset into the defect, and the muscle fascia is sewn to the contralateral gluteus maximus fascia. The subcutaneous tissue is closed in a second layer followed by skin.

7.The donor site is closed directly over a suction drain and additional drains placed under and over the flap. If direct closure is not possible, skin grafting the donor site is an option.

TFL Fasciocutaneous Flap

A fasciocutaneous flap based on cutaneous branches off the lateral descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery. It is commonly used for trochanteric pressure ulcers.

1.The skin paddle is marked: A classic V-Y advancement pattern is used with the central axis running down the mid-lateral thigh.

2.The skin is incised beginning at the apex of the V.

3.The flap is elevated incorporating the TFL.

4.The dissection should be slow at two points: the midway point between the lateral femoral condyle and the greater trochanter, and 12 cm below the greater trochanter. The pedicles are located in these areas.

5.Once the perforators are isolated, the proximal skin is incised, creating an island flap.

6.The flap is advanced into the defect in a V-Y fashion and sewn into place in two layers.

7.After undermining, the donor site is closed directly over a suction drain from distal to proximal, and an additional drain is placed under the flap.

19

TFL Myocutaneous Flap

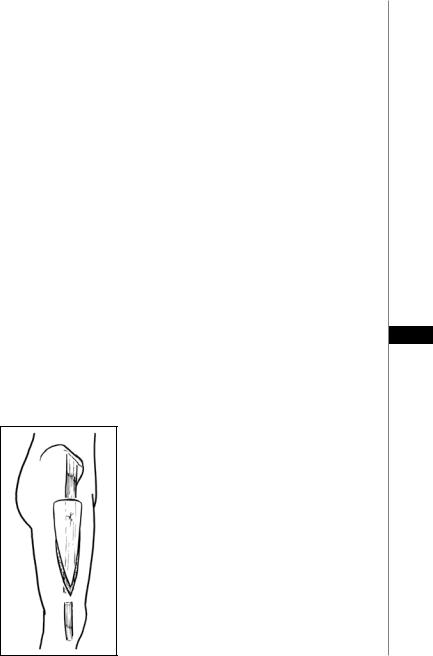

A Type I musculocutaneous flap based on the ascending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery. It is used for trochanteric pressure ulcers.

1.The skin paddle is marked: A classic V-Y advancement pattern is used with the central axis running down the mid-lateral thigh (Fig. 19.3).

Figure 19.3. The Y-Y advancement TFL myocutaneous flap.

108 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

2.The skin and subcutaneous tissue are incised beginning at the apex of the V. The muscle insertion into the lateral aspect of the knee is divided.

3.The flap is elevated along with TFL muscle. Dissection progresses superiorly in the plane deep to the TFL and superficial to the vastus lateralis.

4.The pedicle is encountered roughly 10 cm below the anterior superior iliac spine.

5.Once sufficient mobility of the flap is obtained, it is advanced into the trochanteric defect and sewn into place in two layers.

7.After undermining, the donor site is closed directly over a suction drain from distal to proximal, and an additional drain is placed under the flap.

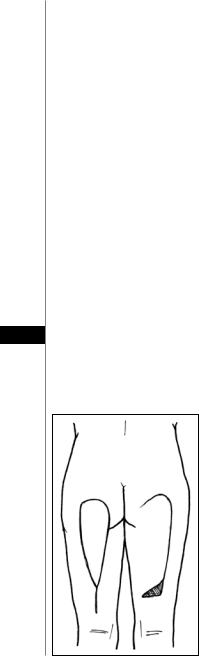

Posterior Thigh Flap

A Type I myocutaneous flap based on the descending branch of inferior gluteal artery. It is commonly used for ischial and trochanteric pressure ulcers. This flap can be solely based on the biceps femoris muscle in ambulatory patients or on all of the hamstring muscles in spinal cord injury patients.

1.The skin paddle is marked either as a rectangle for a medially based rotation or as a triangle for V-Y advancement (Fig. 19.4). Maximum skin paddle dimensions are 12 cm wide by 34 cm in length (never closer than 4 cm to the popliteal fossa).

2.The flap can be advanced, rotated or a combination of both. The point of rotation is 5 cm above the ischial tuberosity.

3.The skin and deep fascia are incised beginning at the most inferior point.

4.The correct plane of dissection is determined by locating the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve and inferior gluteal vessels between the semitendinosus and biceps femoris muscle.

5.The nerve and vessels are divided where necessary and elevated with the flap as the 19 dissection progresses superiorly until the inferior border of the gluteus maximus is

reached. If more reach is needed, fibers of the gluteus maximus can be included.

6.The medial and lateral skin borders are incised creating a skin island on the flap. If very minimal rotation/advancement is needed, the medial skin border can be maintained.

Figure 19.4. The posterior thigh flap. It can be advanced as a V-Y flap (shown on the left leg) or rotated (shown on the right leg).

Pressure Ulcers |

109 |

7.The flap can be advanced or rotated into the defect, or even turned over for a more distal defect.

8.After undermining, the donor site is closed directly over a suction drain from distal to proximal, and an additional drain or two is placed under the flap.

Note: when the descending branch of the inferior gluteal artery is absent—a relatively common anatomical variant—the flap can be elevated as a superiorly based, random, fasciocutaneous flap based on proximal perforators from the cruciate anastomosis of the fascial plexus.

Postoperative Care and Complications

The greatest foes of a fresh flap are pressure or shearing forces. Strict use of an air-fluidized bed for a minimum of 2 weeks postoperatively is a common regimen. Some surgeons will only insist on 10 days of immobilization. Over the next 1-2 weeks, progressive sitting is done starting at 15 minutes twice a day and then increasing the frequency and duration from there. Pressure release maneuvers are performed at least every 15 minutes.

A long course of postoperative antibiotics is not routinely necessary. In cases of known osteomyelitis, or in which the intraoperative bone specimen is positive, 10-14 days of postoperative antibiotics is indicated. Infected ulcers that have been debrided and covered in a single stage procedure should also receive 1-2 weeks of postoperative antibiotics. Suction drains (e.g., Jackson-Pratt bulb drains) are mandatory for pressure ulcer repairs and should be left in place for a minimum of 10 days and often longer if their output remains elevated. Drains help eliminate dead space and reduce the risk of seroma formation. They do not, however, prevent infection or hematoma, the two common early postoperative complications of pressure ulcer repair. After 1-2 weeks, a

breakdown in part of the suture line is not uncommon. It should heal with local 19 wound care within 7 days. If not, it may indicate a deeper wound dehiscence.

Postoperative nutrition must be optimized in order for healing to occur. Adequate protein intake must be maintained by keeping the patient in positive nitrogen balance.

Debilitated patients unable to consume sufficient protein should receive supplemental nutrition. The enteral route is always the first choice. In addition to protein, vitamin C, zinc and other minerals can be supplemented with vitamins or nutritionally rich shakes such as Boost or Ensure. When available, a nutritionist’s help can be valuable in designing a diet that will promote wound healing and a catabolic state.

Later complications include pressure ulcer recurrence (discussed below) and malignant degeneration. “Marjolin’s ulcer” is the term used to describe malignant degeneration of a pressure ulcer and other chronic wounds. The latency is about 20 years. All chronically draining ulcers, especially those that have a change in the character of their drainage or appearance, should be biopsied to rule out malignancy.

Outcomes

Long term follow of patients who have undergone pressure ulcer repair reveal a wide range of recurrence, ranging from 25-80%. Pressure ulcers recur in up to 50% of patients who undergo flap coverage. This high rate of recurrence is independent of the original site of the pressure sore. There is also minimal difference in the recurrence rates between fasciocutaneous and myocutaneous flaps. In some studies, fasciocutaneous flaps have a lower rate of recurrence; however pressure sore recurrence appears to be more dependent on patient factors rather than on the type of flap that was used. As a group, young spinal cord injury patients have the highest risk of recurrence.

110 |

Practical Plastic Surgery |

Pearls and Pitfalls

•When consulted for a fever in a patient with a pressure sore, remember that bacteremia due to a pressure sore is rare, especially when the clinical exam fails to demonstrate an abscess or obvious purulence. Urosepsis is at the top of the differential.

•A pressure ulcer that has a “fish bowl” appearance-a small opening in the skin with a large ulcer cavity beneath it, must have the opening widened so that it can be packed adequately.

•The diagnosis of osteomyelitis should be excluded in all stage IV pressure sores prior to flap coverage. This is easily done with a bone biopsy. Remember to always check for a coagulopathy first.

•Take the time to instruct the nursing staff or consulting service on proper dressing changes and wound care. They will appreciate your input and the patient will have a much better chance of healing.

•Position, prep and drape the patient in a manner that will keep all your options open, including using an alternative flap or harvesting a skin graft.

•When elevating the flap, work from distal to proximal. Dissect quickly where it is safe, but slow down near the pedicle. Once the pedicle is identified, inspect it frequently, especially when changing the direction of dissection.

•Never inset a flap that is under tension, especially the distal tip of the skin paddle. If it doesn’t reach, don’t force it. Careful dissection around the pedicle can provide the extra needed length.

Suggested Reading

1.Coskunfirat OK, Ozgentas HE. Gluteal perforator flaps for coverage of pressure sores at various locations. Plast Reconstr Surg 2004; 113:2012.

192. Cuddigan J, Berlowitz DR, Ayello EA et al. Pressure ulcers in America: Prevalence, incidence and implications for the future. An executive summary of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel monograph. Adv Skin Wound Care 2001; 14(14):208.

3.Evans GRD, Lewis Jr VL, Manson PN et al. Hip joint communication with pressure sore: The refractory wound and the role of Girdlestone arthroplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 1993; 91:288.

4.Foster RD, Anthony JP, Mathes SJ et al. Ischial pressure sore coverage: A rationale for flap selection. Br J Plast Surg 1997; 50:374.

5.Goetz LL, Brown GS, Priebe MM. Interface pressure characteristics of alternating air cell mattresses in persons with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2002; 25:167.

6.Han H, Lewis Jr VL, Wiedrich TA et al. The value of Jamshidi core needle bone biopsy in predicting postoperative osteomyelitis in grade IV pressure ulcer patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002; 110(1):118.

7.Hess CL, Howard MA, Attinger CE. A review of mechanical adjuncts in wound healing: Hydrotherapy, ultrasound, negative pressure therapy, hyperbaric oxygen, and electrostimulation. Ann Plast Surg 2003; 51:210.

8.Horn SD, Bender SA, Ferguson ML et al. The national pressure ulcer long-term care study: Pressure ulcer development in long-term care residents. J Am Geriatrics Soc 2004; 52(3):359.

9.Kroll SS, Rosenfield L. Perforator-based flaps for low posterior midline defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 1988; 81:561.

10.Morykwas MJ, Argenta LC, Shelton-Brown EI et al. Vacuum-assisted closure: A new method for wound control and treatment: Animal studies and basic foundation. Ann Plast Surg 1997; 38(6):553.

11.Ramirez O, Hurwitz D, Futrell JW. The expansive gluteus maximus flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 1984; 74:757.

12.Shea DJ. Pressure sores: Classification and management. Clin Orthop 1975; 112:89.

13.Thomas DR. Improving outcome of pressure ulcers with nutritional interventions: A review of the evidence. Nutrition 2001; 17:121.

14.Yamamoto Y, Tsutsumida A, Murazumi M et al. Long-term outcome of pressure sores treated with flap coverage. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997; 100(5):1212.

Chapter 20

Infected and Exposed Vascular Grafts

Mark Sisco and Gregory A. Dumanian

Infected Arterial Bypass Grafts

Vascular graft infections remain challenging clinical problems for the vascular surgeon, especially when prosthetic material is involved. Traditional approaches, which until the 1960s consisted of removal of all prosthetic grafts with extra-anatomic bypass or amputation, has given way to more conservative approaches in patients whom graft removal is not feasible. These approaches have significantly reduced mortality and improved limb salvage. Contemporary management consists of an escalating algorithm of interventions that range from retention of the graft with healing by secondary intention to graft replacement with muscle flap reconstruction of the defect. When definitive extra-anatomic bypass is not possible, in situ replacement of infected prosthetic grafts with cadaveric homografts or autogenous tissue is preferred. The decision to replace the graft is typically made by the vascular surgeon. This section will focus on reconstructive options in the groin, since it is the most common site of graft exposure and infection requiring plastic surgical intervention.

Preoperative Considerations

Salvage of an arterial graft may be considered in patients who have patency of their reconstruction, an intact anastomosis and localized infection. Systemic antibiotics should be administered preoperatively. Superficial infections that do not extend to the graft itself may be managed with debridement alone, followed by local wound care.

Flap reconstruction is the management of choice for deep infections that involve the graft. This is due to the its well-established utility in lowering bacterial counts, improving antibiotic delivery, filling dead space and providing tension-free soft tissue coverage. Patency of donor vessels to the intended flap must be assessed preoperatively using MRA or angiography. The reconstructive surgeon must know the patency status of the graft before commencing the procedure. Staged debridements may be required prior to reconstruction. Wet-to-dry dressings, hydrogels, or closed suction drains may be used in the interim.

Operative Considerations

Flap options for coverage of groin wounds are listed in Table 20.1. The most commonly used flap in the groin is the sartorius. Harvest of the flap involves detaching from the anterior superior iliac spine, transposing it over the graft and suturing it to the groin musculature and inguinal ligament. Care must be taken not to interrupt more than three perforating vessels to this flap, since its segmental blood supply from the superficial femoral artery puts it at risk for necrosis.

Practical Plastic Surgery, edited by Zol B. Kryger and Mark Sisco. ©2007 Landes Bioscience.