- •60. Plan of Suzdal n the 11th and 12th century (compiled by a. Varganov)

- •Historic buildings

- •61. View of the kremlin ensemble (taken before the restoration of the cathedral)

- •62. Cathedral of the Nativity. Detail of the south portal

- •63. Cathedral of the Nativity. Detail of the south front

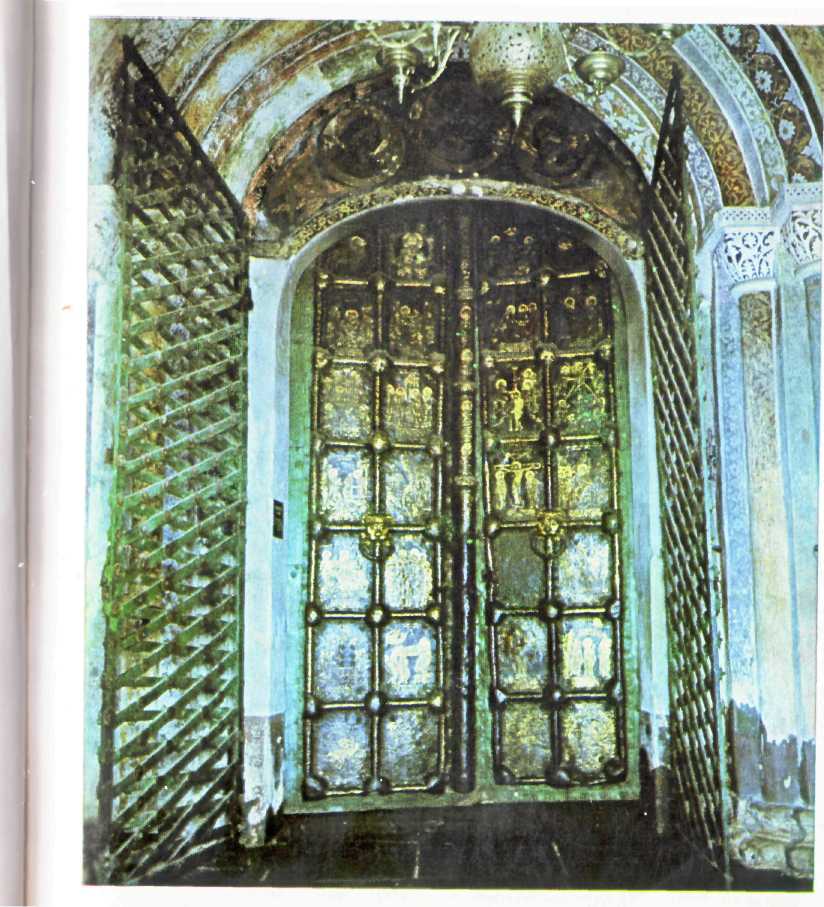

- •66. Western Golden Gates in the Cathedral of the Nativity. 1230-1233

- •69 Details of the western Golden Gates in the Cathedral of the Nativity 1230-1233

- •72. Church of St. Nicholas from the village of Glotovo. 1766

- •73. Church of St. Nicholas. 1720-1739

- •74. Church of St. Cosmas and St. Daminn.1725

62. Cathedral of the Nativity. Detail of the south portal

All this shows a new attitude on the part of the architects, namely, a desire to reinforce the purely decorative element and eliminate its link with the structure of the building. The same approach can be seen in the treatment of the band of blind arcading (111. 63) which no longer bears any relation to the position of the choir-gallery and therefore, like the pilaster strips, gives no indication of the building's internal structure on the outer walls. It is used simply -as a piece of decoration which can be moved up or down at will. The band is deeply recessed producing a vivid interplay of light and shade, but its proportions have changed considerably. Instead of light, slender, tapering columns we see relatively short cylindrical ones that look like carved wooden balusters. The consoles have been turned into a kind of cube-shaped support and all that remains of the elaborate bases is a single round block decorated at the corners with horned griffins. The capitals and the round block beneath them have also become very large. All the elements in the band are densely covered with carving even the row of decorative brickwork is notched with a

herring-bone pattern which blurs the sharp contours of the stone and makes it look more like a row of small round wooden balusters.

63. Cathedral of the Nativity. Detail of the south front

The carving itself is mainly flat and ornamental, reminiscent of wood carving like that which we saw in the Cathedral of St. Dmitri. An excellent illustration of this can be found in the lions on the south portal (Ill. 61) which are carved almost graphically, each line extremely expressive, and also in the wide curve of the archivolt decorated with garlands of twining plants emerging from the tail of a bird. The architects' love of ornament which led them to change the character of certain architectural features justifies the assumption that the upper part of the building was richly decorated with carving just as lavish as that on the Cathedral of St. Dmitrii. There are grounds for thinking that above the band of blind arcading the pilaster strips were more complicated in form and decorated with carving. It is highly likely that the system of covering the wall with a flat carpet of ornament on which high relief carved stones and compositions stand out very clearly, that we shall see later in the Cathedral of St. George at Yuryev-Polskoi, first originated here. There was probably a band of blind arcading along the top of the apses divided by narrow semi-columns.

The outer walls of the narthexes and the cathedral were probably crowned with pointed zakomaras. Above the latter rose three domes: a large one over the point where the transept crosses the nave, and two smaller ones. There are two theories about where the smaller domes stood. They may have been placed on the eastern corners of the cathedral to provide more light for the enlarged sanctuary: this arrangement can be found in Suzdal's sixteenth-century three-domed monastery cathedrals which imitated the main town cathedral. On the other hand a number of twelfth-century buildings suggest that the two domes may have stood on the western corners in order to provide more light for the large choir-gallery. Certain twelfth-century buildings in Polotsk, Pskov and Chernigov, together with the fact that the cathedral's roof collapsed in 1445, suggest that the latter had an unusual design and that the central dome rose above the vaulting on an elevated tower-shaped base, similar to that in the cathedral of the Princess Convent at Vladimir. It is also likely that the western section of the cathedral with its two domes was slightly lower,

giving the building a tiered appearance. If these suppositions are correct the Suzdal cathedral reflects the tendency in Russian architecture of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries to adapt the traditional design of a dome inscribed in a cross in favour of a more dynamic composition. It was evidently a most original and sumptuous building.

One of the important features of the cathedral is the way in which it was adapted to fit in with its surroundings. It stood on the site of the older building erected by Vladimir Monomach quite near to the northern ramparts of the fortress, with its south and east walls facing the town square.

The architects paid special attention to the main south wall and its narthex. The ornamentation here is richer and finer than on the other walls, and the carved portal was transformed, as it were, into a huge icon frame of white stone inside which the panels of the copper gates shone with embossed gold. The patterned carving of the surround linked the portal with the corner pilaster strips of the narthex. The side walls of the narthex were decorated with a striking cornice consisting of two strips of protruding cut stone which produced a rich interplay of light and shade. The ogee-shaped zakomara of the narthex was decorated with carved figures (the centre figure, possibly the Archangel Michael, has been lost and all that remains are the haloes of the figures at the sides) and a wide ornamental band of plants and birds. It was through this lavishly decorated south entrance that the townspeople of Suzdal entered the cathedral. In the east section of the cathedral's south wall there is very elaborate window decorated with a surround of semi-columns with carved bases and capitals.

The west wall facing the prince's courtyard was the second most important one. The front of the west narthex had a broad, impressive carved portal with the soft curves of the archivolt faced with fine stone. It is interesting that here too the various elements are remarkably delicate in spite of the large dimensions of the portal: the semi-columns and ledges are thin and elongated, and the curve of the archivolt is flattened making it look incapable of bearing the weight of the masonry above it. The portal seems to have had no doors, so the narthex was an open one. Beyond it in the wall of the cathedral itself there was a second portal, possibly painted, also with "golden doors". The narthex originally had an upper storey which was destroyed at the end of the seventeenth century. Inside its north wall there was a staircase leading to the upper part of the building and the choir-gallery. The arched entrance, now blocked up, can still be seen in the cathedral wall under the ceiling of the narthex.

64. Painting on a burial niche in the Cathedral of the Nativity. 13th century

The north wall facing the ramparts was much plainer. This is particularly evident in the portal made of thin brick, where the moulding consists merely of a number of rectangular strips without bases or capitals. The only bright touch was its frescoes (the present frescoes date back mainly to the seventeenth century). The band of blind arcading on the north wall was the work of less experienced craftsmen and its subject matter was less varied. Thus, as we have shown, the different walls of the cathedral were decorated in relation to their surroundings.

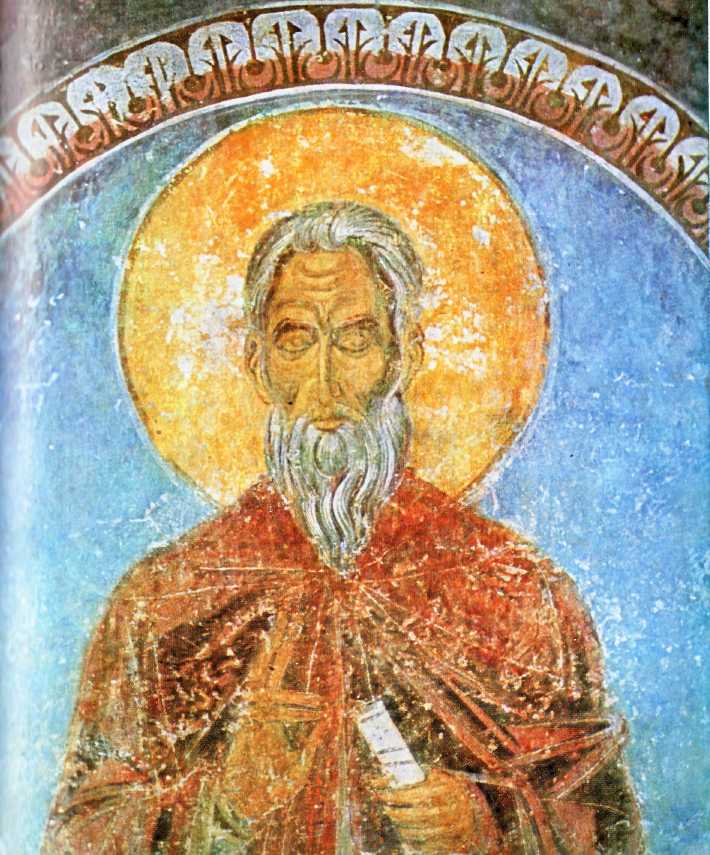

65. Fresco in the Cathedral of the Nativity. 13th century

Let us now go inside the cathedral, bearing in mind that its interior also belongs to two different periods. On the north side of the southwest pillar, about ten feet from the ground, there is a moulded cornice reminding us that the old choir-gallery once rested on these pillars. The gallery was unusually large and its vaulting covered the west ends of the two side aisles dividing them, as it were, into two storeys. The upper storey had plenty of light from the windows in the corner domes and walls. Clearly the large choir-gallery was not intended only for the prince's family and retinue. We have already noted that the entrance to it came from inside the cathedral and was in no way connected with the royal residence. Suzdal's cathedral was the first one that really belonged to the town, and the boyars, rich merchants and master craftsmen also possessed the right to stand in the choir-gallery, after passing through the sumptuous portal of the west narthex and up the staircase in its wall.

The area below the choir-gallery was in semi-darkness, the only sources of light being two small windows in the west wall and the arches of the choir-gallery which opened out into the nave. Beneath the gallery there was a burial vault. Niches were built into the base of the walls of the cathedral and its narthexes for the tombs of the royal family and bishops. This probably explains why the east end of the cathedral was extended increasing its area. Some of the niches still have traces of painting dating back to 1233. The southern niche of the west wall is particularly striking with a gorgeous crimson flower surrounded by twisting fronds, and yellowish stems with dark-blue and pink flowers framing the arch (Ill. 64). However the cathedral's builders and their successors had little opportunity to avail themselves of the burial niches. Thirteen years after the cathedral was completed Suzdal was captured by the Mongols and the burial vault was used mainly for the feudal nobility of later times. The descendants of the Suzdal-Nizhny Novgorod princes were buried here in the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The sanctuary was divided from the main body of the church and the congregation by an altar barrier. This was probably made of white stone and it is possible that the cube-shaped stones with female masks under an ogee arch (Ill. 63) which were inserted into the outer walls above the band of blind arcading bear some relation to it. Investigations have shown that these stones were actually capitals with three faces, the two side ones now being hidden by the brickwork. Similar capitals may have crowned the side posts of the altar gates which led to the sanctuary and the side apses. Old miniatures show pictures of pillars like these with triple-headed capitals and the carved posts of wooden doors.

In 1233 the floor of the cathedral was covered with coloured majolica tiles, large areas being paved with square tiles of yellow, green and dark brown. The section under the main dome and probably by the altar as well was covered with small tiles forming intricate, mosaic-like patterns. The chronicler describes these floors with their shining, glazed surface as "wondrous variegated marble".

In the same year the cathedral was decorated with frescoes which were the work of either Suzdal or Rostov masters summoned by Bishop Kirill. Fragments of them were uncovered by Alexei Varganov in 1938. The best are to be found on the upper part of the south apse. Here we see the restrained figures of two elders with stern, ascetic faces framed by patterned arches on decorated columns (Ill. 65). The gentle precision of the brushwork combined with a certain refinement and restraint show these frescoes to be the work of skilled artists. The variegated foliate and geometrical ornament seems to cover the surface of the wall like a gaily coloured piece of cloth or tapestry. It overshadows the figures of the saints who are lost amid its intricate patterns. This ornamental feature of the paintings in the Suzdal cathedral served as one of the main models for the foliate carving on the Cathedral of St. George in Yuryev-Polskoi, as we shall see later. It shows the extent to which the Russian people's love of bright colours and elaborate decoration in their buildings had made itself felt in painting. It is evident in the cathedral's ornamental sculpture and precious plate, as well as in the frescoes.

A striking example of it can be found in the magnificent "golden gates" which adorn the cathedral's south and west portals to this very day, real masterpieces of thirteenth-century Russian applied art. The huge doors are divided into rectangular panels by raised rolls. The rich decoration and many small scenes on the panels are executed in a complicated technique of fusing gold on to a dark, velvety background of bronze, against which the gold designs shine out beautifully (Ill. 66). The door handles were shaped in the form of lions' heads with massive rings in their jaws (Ill. 67). The gates were like a huge gold icon gleaming in the carved frame of the portal.

The west gates were adorned with scenes from the Gospels, pride of place being given to the Virgin Mary who was regarded as the patron of the Vladimir lands. Here we find one of the earliest portrayals of the festival of the Intercession which was instituted by the Vladimir church authorities. The lower panels are covered with the figures of lions and griffins surrounded by intricate foliate patterns (111. 68) very similar to the stone animal carvings of the Vladimir-Suzdalian school.

The figures of saints in medallions include St. Mitrophanes, the patron saint of Mitrofanes, bishop of Suzdal from 1227-1238, who commissioned the west gates and was later among those burnt to death by the Mongols in the Cathedral of the Assumption in Vladimir.