- •60. Plan of Suzdal n the 11th and 12th century (compiled by a. Varganov)

- •Historic buildings

- •61. View of the kremlin ensemble (taken before the restoration of the cathedral)

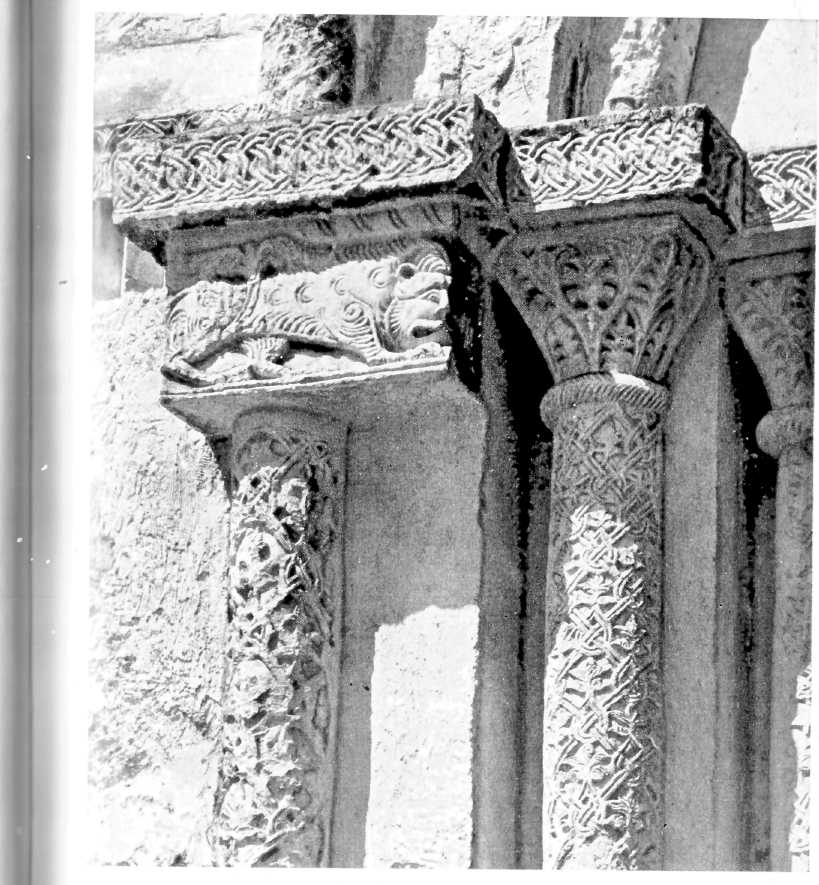

- •62. Cathedral of the Nativity. Detail of the south portal

- •63. Cathedral of the Nativity. Detail of the south front

- •66. Western Golden Gates in the Cathedral of the Nativity. 1230-1233

- •69 Details of the western Golden Gates in the Cathedral of the Nativity 1230-1233

- •72. Church of St. Nicholas from the village of Glotovo. 1766

- •73. Church of St. Nicholas. 1720-1739

- •74. Church of St. Cosmas and St. Daminn.1725

Historic buildings

The obvious starting point for our tour of Suzdal's old buildings is the heart of the old town, the kremlin. We shall approach it by the road leading to the cathedral.

This road crosses the well-preserved moat on the east side of the old fortress, from 100 to 115 feet wide, and the earth ramparts. In the eighteenth century the ram parts were turned into a boulevard. Its green slopes covered with old trees reach a height of 55 feet from the bottom of the ditch and their total perimeter is 1,530 yards. The main entrance tower of the fortress, the wooden Ilyinsky Gates, formerly stood on this spot adjoined by the wooden walls running along the top of the earth ramparts. This east side of the fortress originally looked out on to a flat plain or, as they used to say in the old days, the "assailable" side, and because of this it was particularly well fortified. The southwest Dmitriyevsky Gates led to the old Monastery of St. Dmitri across the river, and the southeast Nikolsky Gates to a bridge over the Kamenka.

On the right immediately behind the ramparts we see the small Church of the Assumption built after 1650 on the site of a former wooden church "in the prince's courtyard" and rebuilt in 1720. This somewhat modest but fine building was restored in 1958 by Alexei Varganov.

The ground on which we are now walking contains remains dating back to the very earliest period of the town's history. Excavations carried out on the left-hand side of the street have revealed dug-outs of the type mentioned earlier and dwellings that once stood above ground level, now all lying deep below the surface. They show signs of having been arranged in a certain order and probably lined the street leading to the kremlin square.

Today the kremlin consists of a number of old buildings grouped round the Cathedral of the Nativity (Ill.61).

The Cathedral of the Nativity, one of the earliest surviving examples of Vladimir-Suzdalian architecture, is more than eight and a half centuries old. When Vladimir Monomach built the Suzdal fortress at the end of the eleventh century he also erected the large town Cathedral of the Assumption. As the stronghold of the Church in an area which had only recently become Christian it was carefully looked after by the authorities and was frequently decorated and repaired. In spite of this, however, it soon began to collapse. Prince Georgi, the son of Vsevolod III, ordered it to be dismantled and a new cathedral of white stone was erected in its place (1222-1225).

61. View of the kremlin ensemble (taken before the restoration of the cathedral)

Excavations by the south wall of the present building have revealed some extremely interesting remains of the original cathedral. They show that it was built of thin bricks set in a lime cement mixed with small pieces of brick, which was a technique widely used in Kiev. The cathedral was almost the same size as the present one, i.e., it was a large six-pillared building with a narthex on its west side and three apses. A fragment of its frescoes has been preserved on the lower part of the wall. Judging by the brickwork the cathedral was the work of Kiev builders brought here by Vladimir Monomach. They also organised the manufacture of the building materials here. The bricks were baked in specially built kilns along the banks of the Kamenka and the lime was prepared in large circular stoves inside the fortress itself not far from the building site. Traces of these installations have also been discovered during excavations. There are grounds for thinking that the prince's palace lay to the west of the cathedral, but we do not know whether it was built of brick or stone.

This great cathedral with its clear, bright interior glowing with beautiful frescoes undoubtedly made a very powerful impression on the townspeople who lived huddled together in tiny, smoke-filled dug-outs and hovels. It must have overwhelmed them with a sense of the power of their new God and the majestic strength of their rulers who had created a "house of God" of matchless beauty.

There was no attempt to restore the cathedral when it began to collapse at the end of the twelfth century. The walls still stood firm and had to be hacked away at their foundations when it was being dismantled. It is possible that the severe brick cathedral with its bare outer walls divided by flat pilaster strips no longer suited the new architectural tastes of the people in the thirteenth century who were more impressed by the richly decorated Cathedral of St. Dmitri in Vladimir and the dazzling beauty of the new white stone churches. The chronicle stresses that in the years 1222 to 1225 Prince Georgi erected a new cathedral "more fair than the first", i.e., the original one. Bishop Simon of Vladimir who helped to compile the Kiev patericon, a collection of stories about the lives of monks at the Monastery of the Caves in Kiev, played a part in the cathedral's construction.

Unfortunately this cathedral has not survived intact. In 1445 the roof collapsed. In 1528 the walls were dismantled down to the decorative band of blind arcading and in 1530 the upper section was rebuilt in brick and topped with the usual five-domed roof. At the end of the seventeenth century the old choir-gallery was destroyed and the narrow, slit windows were widened. In 1750 the cathedral was given huge, onion-shaped domes and the roof, which had formerly followed the shape of the zakomaras, was replaced by a simple hipped one. In I he eighteenth and nineteenth centuries adjoining structures were built on to the north and west walls. In 1870 the outer walls were plastered with mortar and painted a muddy red. The later adjoining structures were removed in 1954 and the cathedral was carefully restored by Alexei Varganov and Igor Stoletov in 1964. We can reconstruct a picture of the original thirteenth-century cathedral from the remaining lower tier and information from other sources.

If we recall the Cathedral of the Assumption in Vladimir in its original form (1158-1160) we can see immediately from the exterior of the Suzdal cathedral that we are dealing here with the same type of building. It is a large town cathedral, elongated lengthwise due to the sharply protruding apses which make it look like an eight-pillared building inside. The main entrances are adjoined by narthexes on all three sides giving the cathedral a cruciform appearance. The outer walls are divided by pilaster strips and surrounded by a decorative band of blind arcading. In many ways, however, the cathedral differs greatly from the specimens of twelfth-century architecture which we have examined.

It is built for the most part of rough slabs of porous tufa forming an uneven surface which was originally covered with nothing but a lime coating. Only a few of the smaller details were made of hewn white stone: the socle, the pilaster strips on the outer walls, the semi-columns on the apses, the band of blind arcading and the carved portals. This was the result more of new tastes than the desire to economise by using a cheaper material. The clearly etched stone carving shows up very strikingly against the rough background of the walls. The architects have, as it were, combined the taste for a refined decorative finish characteristic of Vladimir architecture with the simple somewhat coarse wall texture reminiscent of churches in Novgorod and Pskov.

The division of the outer walls was simplified, elaborate pilasters and semi-columns being replaced by narrow, flat pilaster strips. The latter no longer corresponded exactly to the interior pillars with the result that this basic element for dividing the outer walls no longer reflected the building's structure. Whereas twelfth-century architects regarded the pilaster strip as an essential structural element for strengthening the walls at the points of tension in the vaulting, we now see them as narrow thin strips stuck on to the wall with the sole purpose of dividing it into sections. The pilaster strips themselves are intersected by a band of ornamental carving and reliefs of lions and griffins inserted on their corners, which were even further removed from their original structural function. In this connection, the south portal (Ill. 62) is particularly interesting. The clear link between twelfth-century portals and their structural elements is almost totally lacking here. The shape of the archivolt does not correspond to the face of the portal, its outside semi-columns are crowned with carved slabs instead of the usual capital, and the inside column stands somewhat apart from the masonry and is broken up by decorative beading, etc.