- •Note-Taking Strategies and Techniques. Teaching and practicing of note-taking

- •3.1. What to Note

- •3.1.1. Main Ideas

- •3.1.2. The Links

- •3.1.3. Noncontextualized Information

- •3.1.4. Verb Tenses

- •3.2. How to Note

- •3.2.1. Shortenings

- •3.2.2. Abbreviations

- •3.2.3. Symbols

- •3.2.4. Layout of Notes

- •Vertical (Diagonal) Layout

- •54, Prices

- •3.3. When to Note

- •3.4. Which Language to Use in Note-Taking

- •3.5. Reading Back Notes

- •3.6. Teaching and Practicing of Note-Taking.

- •3.6.1. Teaching Note-Taking to Students

- •3.6.2. Exercises on Practicing Note-Taking

- •Variants of links used:

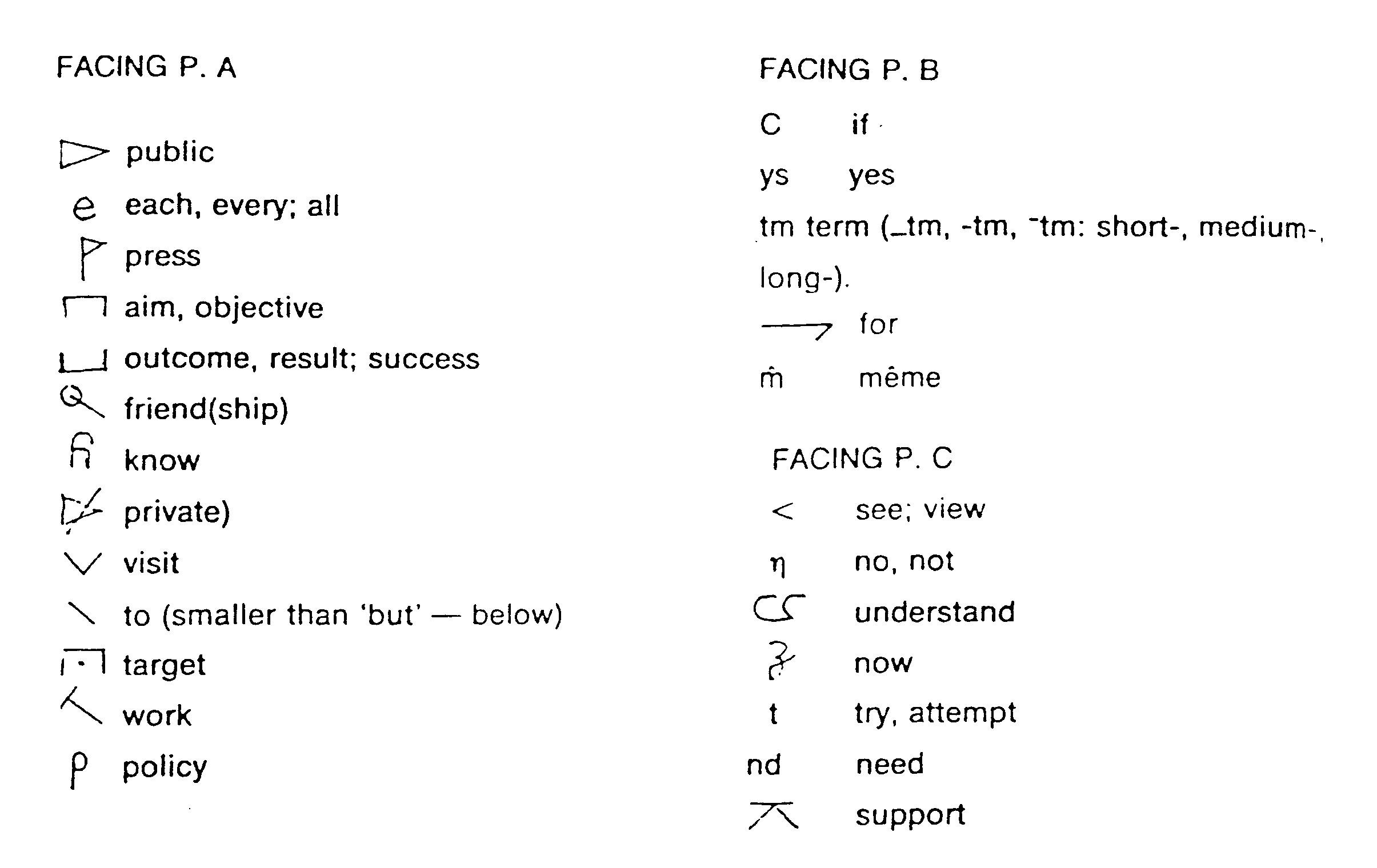

3.2.3. Symbols

Although shortenings and abbreviations are commonly used in notes, their most prominent drawback is that they tend to entice the interpreter to stick to the word level instead of meaning level. In other words, it easily leads the interpreter to think in terms of words rather than ideas, which could harm the interpretation. Therefore symbols are more preferable for their capacity of representing ideas and eliminating source language interference.

A "symbol" is anything, a mark, sign or letter used to represent a thing or a concept. Symbols are quicker and easier to write than words. Firstly, symbols need to be prepared and mastered in advance (similar to abbreviations). Any symbol improvised in the middle of interpretation could drive the interpreter into a difficult and intense situation. In this respect, Daniel Gile says: “In consecutive interpretation, using many symbols in note-taking helps reduce the time required to note ideas. However, until they are mastered, retrieving them from memory and/or recognizing their meaning from memory and/or recognizing their meaning from the notes in the reformulation phase may require more time and processing capacity than would be the case when writing plain words.” [36:172].

The use of symbols and abbreviations should be automatic because any new one created in the process of interpreting may require so much attention. It is unacceptable for the interpreter to be distracted from his work for any reasons at all. Only by developing his own system of abbreviations and symbols beforehand can the interpreter make them come to his pen automatically.

Based on the above, there is one basic rule for the interpreter: only use the symbols which are already stuck in the mind. Secondly, symbols must be consistent. That means symbols are instantly associated for the interpreter himself with the meaning he gives them. Attending to this point, the interpreter can avoid mistakenly “deciphering” the meaning of the symbols he or she uses.

The interpreter is the only person who needs to read and understand the meaning of abbreviations and symbols in his notes; he must be the creator of his own system, which then has a logical meaning. Therefore, the interpreter should not compel himself to learn by heart an artificial complicated system of abbreviations and symbols built by others in the same way as one may learn mathematical formula or dramatic poems because such abbreviations and symbols require too much space in the memory. Unavoidably, this would make it harder for the interpreter to focus on listening, understanding and analyzing the original.

John A. Henderson in his article Note-Taking for Consecutive Interpreting published in Babel in 1976 [40:115] gives an example of the system of symbols, developed by a student of his, and comments on them:

“This particular student has evolved an unusually complex system of notes and symbols, which many may consider too elaborate. Such opinions are of course irrelevant: the only significant criterion is that he is able to follow them with ease and interpret from them (and memory) without hesitation. Fortunately, he has also kindly provided a key, enabling most notes to be understood (additional comments below the transcript - refer to numbers in the right-hand margin):

This example could of course be improved in some details and it is evident that its author relies fairly heavily on memory. It is also obvious that he is a distinctly above average student who has worked hard at developing his own system. He is however far from being the only graduate of the course to find employment as a conference interpreter.” [40:115-116]

One could say that symbols clearly help the interpreter take notes more quickly and effectively, and then it is wise to use as many symbols as possible. However, it does not seem reasonable to set up a rigidly unchanged rule for a degree of symbolization, each interpreter through practice would find their own balance. For some interpreters, symbolizing as much information as possible is good. For others, it is not necessary to do so.

James Nolan in his book “Interpretation. Techniques and Exercises” gives some basic guidelines on using symbols and abbreviations at note-taking that should be followed:

Adopt and use symbols that are useful for the subjects you are dealing with.

Always use a symbol to mean only one thing in a given context.

Use pictorial or graphic devices like circles and squares or lines and arrows. You are not “writing out the speech”; you are “drawing a picture for yourself” of the speech.

Arrange your notes on the page in a meaningful way (for example, with the main points at the top and minor points at the bottom). Use indentations logically and consistently.

Learn and use conventional abbreviations and acronyms (for example, the telegraphic business abbreviation “cak” meaning “contract”, or the morse-code acronym SOS to mean “help”.

Adopt a simple, one-stroke symbol which, whenever you write it, will mean “the main subject of the speech”.

Adopt a simple sign which will mean “three zeroes”, so that you can write down large numbers quickly (for example, if – means “three zeroes”, then 89 – – means “89 million”). Adopt another symbol to represent two zeroes.

Adopt or coin abbreviations or acronyms for often-used phrases (examples: asap = as soon as possible; iot = in order to; iaw = if and when.

Invent symbols for common prefixes and suffixes, such as “pre-“, “anti-“ or “-tion”, “-ment”.

When you write out words, do not double any consonants, and delete any vowels that are not necessary to make the word recognizable or to distinguish it from another similar word. [54:295]

Once you have adopted a symbol and assigned it a specific meaning, you can then build other symbols from it. For example, if the symbol x is used to mean “time”, the following variations on it are possible:

-

x–

timeless, eternal

xx

many times, often

xx+

many times more

xx–

many times less

x t x

from time to time, occasionally

=x

equal time

+x

more time, longer time

–x

less time, shorter time

2x

twice

3x-/

three times less than

100x

a hundred times

100x+

a hundred times more

Ltdx

a limited time

oldx

old-time, old fashioned

x!

It’s time, the time has come

gdx

a good time

x)

time limit, deadline

x>

future

<x

past

ovrx

overtime

xng

timing

xtbl

timetable, schedule

prtx

part-time

x,x

time after time, repeatedly

wrx

wartime

Table 8: Variations of the symbol x denoting concept of time

There are many sources of symbols. You will find them all around you, even on signs in the street. It does not matter from what source you borrow your symbols, so long as you use them consistently in your own note-taking system. Look for symbols that can be written quickly and easily, with few pencil-strokes. The following are a few possible sources of symbols:

proofreader’s marks (see, for example, back matter of dictionaries);

symbols or abbreviations from dictionary entries, like ~ ;

mathematical and algebraic symbols, like +, – , = , < , > , , ;

books on semiotics;

ancient writing systems, like Norse or Cuneiform;

conventional business and commercial symbols and abbreviations, like @, £, CIF or ASAP;

foreign-alphabet letters;

pictographs borrowed from languages with pictographic script, like Chinese (for example, to mean “standing”);

pictographs and pictographic devices borrowed from ancient hieroglyphic scripts (for example, runes, or the ancient Egyptian device of enclosing the proper names of important people in a “cartouche”);

punctuation marks, like ! or ? or / (for example, you could use +/ to mean “and or”, and the ampersand (&) to mean “and”);

signs of the zodiac;

pronunciation symbols, accents, diacritical marks;

capital letters used for a specific meaning, like P to mean president, or F to mean France; or single letters used for a specific meaning, like c to mean “country”;

children’s “picture-writing” (e.g. ^ to mean “house” or “shelter”, or ☺ (to mean “happy” or “pleased”, or ♥ to mean “love”)

symbolic logic;

scientific symbols, like ♂ for “man” and ♀ for “woman”;

musical signs;

legal symbols, like § to mean “section”;

monograms (combinations of letters, such as Æ)

In appendixes to this research, there are some symbol examples retrieved from electronic source at Interpreter Training Resource.