Economics_-_New_Ways_of_Thinking

.pdf

Working After School:

What Are the Trade-Offs?

Through our study of economics, we learn that there are trade-offs in life. More of one thing often means less of something else. Spending more money on

clothes means less money for entertainment. More time spent studying means less time to hang out with your friends.

One of the major trade-offs high school students face is whether or not to work after school. Some people argue that high school students should work after school; others argue against it, saying their time is better spent studying. Let’s hear what five people have to say.

Rebecca Clark,

a junior in high school

Iwork after school and on the weekends at a fast-food restaurant here in town. It may

be hard to believe, but I actually like the work. I meet a lot of nice people, I earn some money, and I am developing a good work ethic. When I first went to work, I thought it was going to be easier than it turned out to be. I thought I was just going to have some fun and make some money. But I’ve learned that to do a job well you have to be conscientious, follow orders closely, and focus on what you are doing. These are qualities that I think will benefit me throughout my life. I think I am a better person because I work. My parents are concerned about how work takes time away from my studies, but I never was much of a student. If I weren’t working, I might be just wasting my time. I might even get into some trouble.

Tommy Sanchez,

a senior in high school

Iknow I could work after school, but I choose not to. Working after school would

come at too high a price for me. If I worked after school, I wouldn’t have as much time to study. I want to get into a really good college and to do that I need to have high grades. If I worked, I probably couldn’t get the A’s that I am currently getting in my courses. The way I look at it, I will have 40 or 50 years to work. I am young now and I like learning, and the more I learn, the brighter my future will be. I think I would be sacrificing my future if I worked after school now.

My older brother didn’t work at a job when he was in high school. He spent most of his time studying. As a result, he got high grades and a good score on the SAT. What is even more important is that he got into Yale. He received a top-quality education at Yale and made many good future business contacts. In fact, he now works in a company owned by the father of one of his best friends at Yale.

Some of my friends talk about the money they make in their after-school jobs. They can buy a lot of things that I can’t. They buy better clothes, and some of them have even bought a car. I’d like to have a car, too, but I don’t want to take away from my studies right now to get a job just so I can buy a car.

Bob Neidelman, parent

Ithink it is important for teens to develop a sense of responsibility and that’s why I have urged my daughter to get a job after school and on the weekends. I worked when

84 Unit I Introduction to Economics

I was her age, and I learned a lot from what I did. Mainly, I learned the value of a dollar. I know that people say teens should not work, that they should devote more time to their education, but the truth of the matter is there are different types of education. There is the book-learning type of education, where a person learns geometry, calculus, English literature, and history. And then there is the education that you receive from getting out in life and working. When you work, you learn how to get along with people. You learn to persevere in order to get a job done. These are important things to learn. In the long run they’ll be more important to her than learning how to solve calculus problems.

Nancy Drummon, guidance counselor

Ithink working after school is good for some students and not for others. It really

depends on the trade-offs the particular student faces. For instance, I often get students in my office who work but who are doing poorly in their courses. I tell them they would be better off if they didn’t work, but instead spent their time after school studying and trying to get their grades up.

But I’ve got other students who are doing well in their courses and feel they can continue to do well even though they get jobs. I see working as a good idea. Not only will they learn some things in their work that they might not otherwise learn, but they will have a little extra spending money, too. There are things they want to do and buy, and working gives them the opportunity to do those things.

I think that whether or not a student should work depends on the individual student. Not all students face the same trade-offs. What is right for one student may not be right for another.

Amy Yoshii, college student

Iworked all through high school, and I really regret it now. I worked for all the

wrong reasons. I worked simply to get the money to buy the same things my friends were buying. My friends were spending a lot of money on clothes, so I thought I had to, too. I worked to get a down payment for a car. Once I bought the car, I had to continue to work so I could make the payments and keep it running. There were many weekends when I was dead tired from working. I’d come home Sunday night, after working all day Saturday and all day Sunday, and have to study for a biology or calculus test. I can’t tell you how many times I just went to bed, telling myself I would get up early and study. The alarm clock would ring, and I’d shut it off. I paid the price in lower grades.

I got into college, and I am doing better now, but college hasn’t been easy for me. I think if I had worked less in high school, and studied more, college would have been more enjoyable, and easier.

I’ve learned that it is extremely important to prioritize—a person just can’t do too many things and do them well. The world we live in values education a lot. You can’t cut corners when it comes to your education. Working just gets in the way. My advice to any high school student is if you don’t have to work, don’t. Study more, work less. You’ll be glad you did in the long run.

What Do You Think?

1.Who do you most nearly agree with? Why?

2.Do you think there is a trade-off between education and work? Why or why not?

Unit I Introduction to Economics |

85 |

C H A P T E R 4

Demand

C H A P T E R 5

Supply

C H A P T E R 6

Price: Supply and

Demand Together

86

“Start with the idea

that you can't repeal the laws of economics. Even if they are

inconvenient.”

—Larry Summers

87

Why It Matters

Certain people and institutions play important roles in your life. For example, your parents, teachers, and friends are impor-

tant. Government is an institution that also plays an important part in your life. It determines such things as when you can get a driver’s license, the amount of taxes you must pay, and when you will be able to vote.

Markets also have a major impact on your life. A market is any place where people come together to buy and sell goods or services. Markets determine what prices you pay for computers, cars, television sets, books, and clothes. Markets also determine what peo-

ple earn as teachers, truck drivers, television and movie stars, baseball players, and nurses. How much money you earn in the future will depend on markets.

If you are interested in the prices you pay for the goods and services you buy, or in why some people earn higher salaries than others, then you will be interested in learning how markets work. The first step is to learn about demand, the subject of this chapter.

88

The following events occurred one day in June.

9:03 A.M. Sam is a student at a technical college in New York City. He is currently working on one of the computers in the school library. He’s not doing any research right now; instead, he’s online checking the prices of various stocks. He recently

inherited some money and is thinking of investing it in the stock market. He checks the share price of various stocks: Georgia Pacific, General Motors, Microsoft, and Dell. He is thinking

about buying 100 shares of Dell, current price $39.35. He is about to place his order online with his online broker, when he has second thoughts. A friend of his told him that the

price of tech stocks, including Dell, would probably be going down this week. Maybe, Sam thinks, I should wait until later to buy this stock.

• What does the (expected) future price of a share of stock have to do with buying stock today?

10:41 A.M. A U.S. senator is in his office talking with his staff. He is concerned about teenage smoking in America. He wonders whether he, as a

U.S. senator, can do anything to reduce the amount of teenage smoking. One member of his staff says that the federal government should increase the tax on a pack of cigarettes. “That way,” he says, “a lot of these kids will stop smoking.” “How so?” asks the

senator. “The tax will push up the overall price of cigarettes,” the staffer says, “and that will lead to teens buying fewer cigarettes.” Another staffer enters the conversation. “I am not so sure many teens will stop smoking,” she says. “If they are really hooked on cigarettes, I think they may keep on buying just as many cigarettes, even at the higher price.”

• Will higher taxes on cigarettes cut down on the number of packs of cigarettes teens purchase? Will higher taxes cut down on the amount of money teens spend on cigarettes?

11:35 P.M. Evan is sitting up in bed reading a magazine. He turns the page of the magazine and looks at an ad about a hotel in Dallas. Under the name of the hotel are the words “The greatest hotel in the world.” Evan reads the magazine for a few more minutes, then turns out the light in his bedroom, and goes to sleep.

• What is the purpose of the Dallas hotel calling itself “the greatest hotel in the world”?

89

Understanding

Demand

Focus Questions

What is demand?

What is the difference between demand and quantity demanded?

Why do price and quantity demanded move in opposite directions?

What is the law of diminishing marginal utility?

What is the difference between a demand schedule and a demand curve?

Key Terms

market demand

law of demand quantity demanded

law of diminishing marginal utility demand schedule

demand curve

market

Any place where people come together to buy and sell goods or services.

demand

The willingness and ability of buyers to purchase different quantities of a good at different prices during a specific time period.

law of demand

A law stating that as the price of a good increases, the quantity demanded of the good decreases, and that as the price of a good decreases, the quantity demanded of the good increases.

What Is Demand?

A market is any place where people come together to buy and sell goods or services. Economists often say a market has two sides: a buying side and a selling side. In economics, the buying side is referred to as demand, and the selling side is referred to as supply. In this chapter, you will learn about demand; in the next chapter, you will learn about supply.

The word demand has a specific meaning in economics. It refers to the willingness and ability of buyers to purchase different quantities of a good at different prices during a specific time period. Willingness to purchase a good refers to a person’s want or desire for the good. Having the ability to purchase a good means having the money to pay for the good. Both willingness and ability to purchase must be present for demand to exist. It is important for you to remember that if either one of these conditions is absent, there is no demand.

Cruz doesn’t have the $34,000 needed to buy a particular car. If she did have the money, though, she says that she certainly would buy the car. Notice that

Cruz doesn’t have the $34,000 needed to buy a particular car. If she did have the money, though, she says that she certainly would buy the car. Notice that

Cruz has the willingness (she wants the car), but not the ability (not enough money) to buy the car. Under these circumstances (willingness, but not ability, to buy), Cruz does not have a demand for the car.

Molly is shopping for a new cell phone. The one she likes is $129, which is within her price range. She was worried that she wouldn’t have enough money, but she has set aside just enough for the new phone. Because Molly has the willingness and the ability to buy the cell phone, demand does exist.

Molly is shopping for a new cell phone. The one she likes is $129, which is within her price range. She was worried that she wouldn’t have enough money, but she has set aside just enough for the new phone. Because Molly has the willingness and the ability to buy the cell phone, demand does exist.

What Does the Law of

Demand “Say”?

Suppose the average price of a compact disc rises from $10 to $15. Will customers want to buy more or fewer compact discs at the higher price? Most people would say that customers would buy fewer CDs.

Now suppose the average price of a compact disc falls from $10 to $5. Will customers want to buy more or fewer compact discs at the lower price? Most people would say more.

90 Chapter 4 Demand

If you answered the questions the way most people would, you instinctively understand the law of demand. This law says that as the price of a good increases, the quantity demanded of the good decreases. The law of demand also says that as the price of a good decreases, the quantity demanded of the good increases. In other words, price and quantity demanded move in opposite directions. This relationship (you have probably heard it referred to as an inverse relationship in your math classes) can be shown in symbols:

Law of Demand

If P ↑ then Qd ↓ If P↓ then Qd ↑

(where P price and Q d quantity demanded)

If you were reading closely, you probably noticed two words that sound alike: demand and quantity demanded. Don’t make the mistake of thinking they mean the same thing. Demand, as you learned earlier, refers to both the willingness and ability of buyers to purchase a good or service. For example, if an economist said that Karen had a demand for popcorn, you would know that Karen has both the willingness and ability to purchase popcorn.

Quantity demanded is a new and different concept. It refers to the number of units of a good purchased at a specific price. For example, suppose the price of popcorn is $5 a bag, and Karen buys two bags. In this case two bags of popcorn is the quantity demanded of popcorn at $5 a bag. As you work your way through this chapter, you will see why it is important to know the difference between demand and quantity demanded.

isfaction gained from each additional unit of the good decreases. For example, you may receive more utility (satisfaction) from eating your first hamburger at lunch than your second

and, if you continue, more utility from your second hamburger than your third.

What does this have to do with the law of demand? Economists state that the more utility you receive from a unit of a good, the higher price you are willing to pay for it; and the less utility you receive from a unit of a good, the lower price you are willing to pay for it. According to the law of diminishing marginal utility, individuals eventually obtain less utility from additional units of a good (such as hamburgers), so it follows that they will buy larger quantities of a good only at lower prices. And this is what the law of demand states.

quantity demanded

The number of units of a good purchased at a specific price.

law of diminishing marginal utility

A law stating that as a person consumes additional units of a good, eventually the utility gained from each additional unit of the good decreases.

Why Do Price and Quantity

Demanded Move in

Opposite Directions?

The law of demand says that as price rises, quantity demanded falls, and that as price falls, quantity demanded rises. Why? According to economists, it is because of the law of diminishing marginal utility, which states that as a person consumes additional units of a good, eventually the utility or sat-

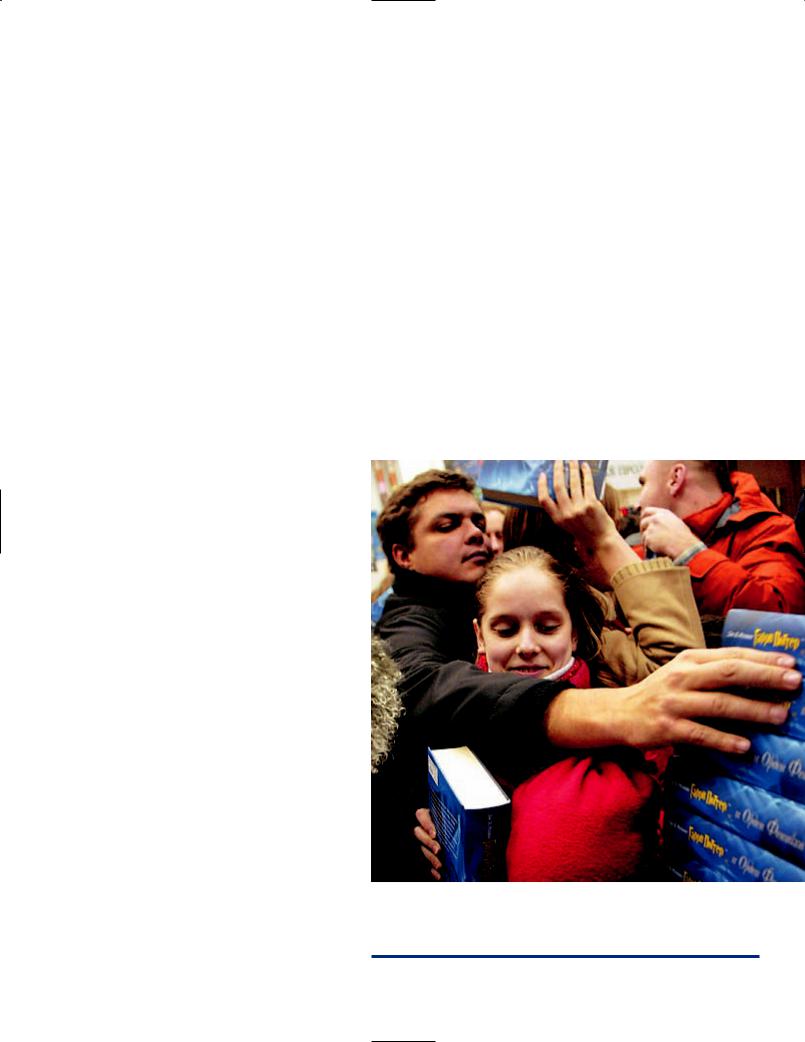

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix was in great demand hours after its release in Russia in early 2004. Do these people have both willingness and ability to purchase?

Section 1 Understanding Demand 91

thePrices Are??? atDisneyland

Goofy?

$126. Disneyland does not charge visitors double its one-day ticket price for visiting two days; it charges $85. Similarly, triple the price of a

The Walt Disney Company operates two

major theme parks in the United States: Disneyland in Anaheim, California, and Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida. Each year millions

of people visit each park. Regardless of which park

you visit, the price you pay for your ticket will depend on how

many days you want to spend at the park. For example, Disneyland’s Web site lists prices for oneto five-day tickets. On the day we checked, the various ticket prices were as follows:

•One-day ticket, $63

•Two-day ticket, $85

•Three-day ticket, $109

•Four-day ticket, $129

•Five-day ticket, $139

Notice that the price of a oneday ticket ($63), when doubled, is

one-day ticket would be $189, but Disneyland charges $109 for a three-day ticket.

Disneyland seems to be telling visitors that if they want to visit the theme park for one day, they have to pay $63, but a second day will cost only $22 more, not $63 more. Notice that the price Disneyland charges to stay a fifth day is only $10 more than staying four days. Do you wonder how much Disneyland would charge to stay, say, a tenth day? By the tenth day,

it might be that you would only have to pay 25 cents more.

Why does Disneyland charge less for the second day than the first

day? It’s because of the law of diminishing marginal utility, which states that as a person consumes additional units of a good, eventually the utility (satisfaction or happiness) from each additional unit of the good decreases. Disneyland can’t charge as high a price when utility is low as when it is high. If you have never been to Disneyland, or haven’t been for five years, your first

day is likely to be quite enjoyable. If you’ve already spent, say, two days at Disneyland, your third consecutive day isn’t likely to give you as much utility as your first.

Can you think of a good or service that is

priced the way visits to Disneyland are priced (for two units of the good or service, you pay less than double what you pay for one unit)?

demand schedule

The numerical representation of the law of demand.

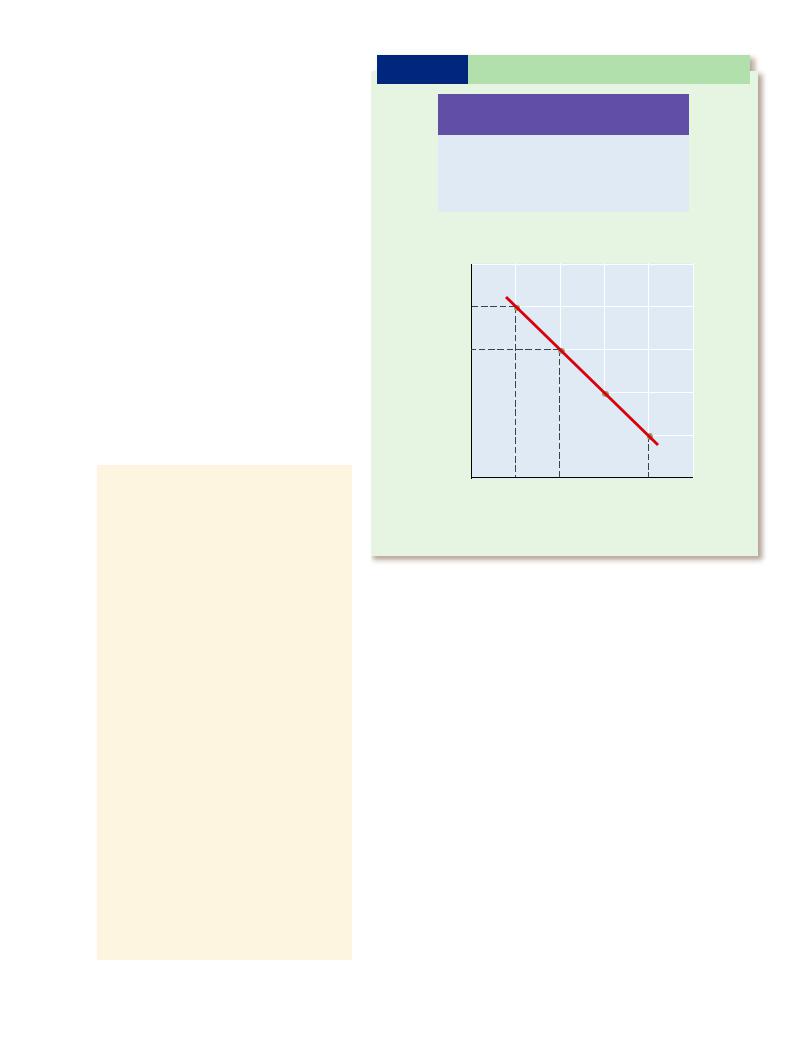

The Law of Demand in

Numbers and Pictures

The law of demand can be represented both in numbers and pictures. Look at Exhibit 4-1(a), which has a “Price” column and a “Quantity demanded” column. Notice that as the prices fall (from $4 to $3 to $2 to $1), the quantity demanded rises (from 1 to 2 to 3 to 4). Do you see that price and quan-

tity demanded are moving in opposite directions? The economic term for this type of numerical chart showing the law of demand is demand schedule.

Now let’s see how you would illustrate the law of demand in picture form. The simple way is to plot the numbers from a demand schedule in a graph. Look at Exhibit 4-1(b), which shows how the combinations of price and quantity demanded

92 Chapter 4 Demand

in Exhibit 4-1(a) are plotted. The first combination (a price of $4 and a quantity demanded of 1) is labeled as point A. The second price and quantity demanded combination ($3 and a quantity demanded of 2) is labeled B. The same process continues for points C and D. If we connect all four points, from A to D, we have a line that slopes downward from left to right. This line, called a demand curve, is the graphic representation of the law of demand.

You might be wondering why we use the word curve when, as you can see in Exhibit 4-1(b), we ended up drawing a straight line to represent demand. The answer has to do with the standard practice in economics, which is to call the graphic representation of the relationship between price and quantity demanded a demand curve, whether it is a curve or a straight line.

QUESTION: I’ve seen a car, a radio, and a diamond ring in the real world, but I’ve never seen a demand curve in real life. (I have seen one in this textbook, though.)

Do demand curves exist in the real world?

ANSWER: If you go outside and look up into the sky, you’re not going to see a demand curve. If you look under your bed or in the school auditorium, you won’t see a demand curve, which doesn’t mean that demand curves don’t exist in the real world. (You also can’t see a virus with the naked eye, but that doesn’t mean viruses don’t exist.)

The data (numbers) that make up a demand curve—combinations of price and quantity demanded—do exist in the real world. When people (in the real world) buy more of a good (such as a can of soda or a new pair of jeans) at a lower price than at a higher price, they are expressing the law of demand, which is graphically portrayed as a demand curve (in a textbook). So what do you think? Do demand curves exist in the real world?

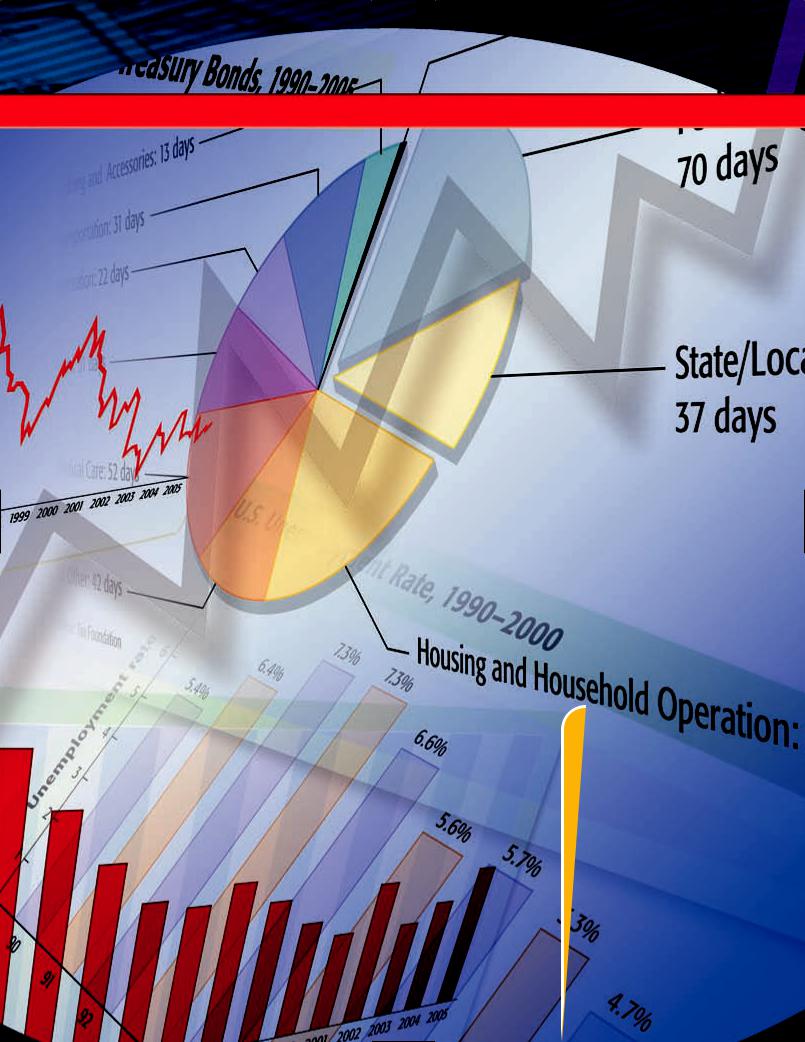

E X H I B I T 4-1 Demand Schedule and Demand Curve

Price |

Quantity demanded |

(in dollars) |

(in units) |

|

|

$4 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

3 |

|

2 |

|

|

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

(a) |

|

|

|

$4 |

|

A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

s) |

|

|

|

|

Demand |

(in dollar |

$3 |

|

B |

|

|

|

|

curve |

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

C |

||

Price |

$2 |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$1 |

|

|

|

D |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

Quantity demanded (in units)

(b)

(a) A demand schedule for a good. Notice that as price decreases, quantity demanded increases. (b) Plotting the four combinations of price and quantity demanded from part (a) and connecting the points gives us a demand curve. Price, on the vertical axis, represents price per unit of a good. Quantity demanded, on the horizontal axis, always applies to a specific time period (a week, a month, a year, and so on).

Individual Demand Curves

and Market Demand Curves

An individual demand curve and a market demand curve are different. An individual demand curve is what it sounds like: the demand curve that represents an individual’s demand. For example, Harry’s demand curve represents Harry’s (and only Harry’s) demand for, say, DVDs. A market demand curve is simply the sum of all the different individual demand curves added together.

demand curve

The graphical representation of the law of demand.

Section 1 Understanding Demand 93