Турук Management

.pdf

GRAMMAR REFERENCE

Функции Participle I

1. Определение, которое может стоять перед существительным. В этой функции перфектные формы причастия не употребляются. Переводится на русский язык как причастие, а иногда как обычное прилагательное.

The reading boy – читающий мальчик

Participle I может стоять после существительного. В этом случае после Participle I могут стоять прямое дополнение и обстоятельство, которые в целом образуют причастный оборот. Переводится причастный оборот на русский язык придаточным определительным предложением или причастным оборотом.

The boy reading a book is my friend. Мальчик, читающий книгу, – мой друг.

2. Часть сложного дополнения.

I see him speaking with a manager.

ßâèæó, ÷òо он говорит с менеджером.

3.Обстоятельство времени, образа действия, причины и переводится как деепричастие.

Having discussed this problem they came to the conclusion. Îáñóäèâ проблему, они пришли к заключению.

4. Participle I может быть частью самостоятельного причастного оборота (The Absolute Participle Construction), т.е. такого причастного оборота, в котором перед причастием стоит существительное в общем падеже или местоимение в именительном падеже, являющееся субъектом действия, выраженного причастием.

Такой оборот отделяется запятой и переводится на русский язык придаточным предложением, если стоит в начале предложения.

Weather permitting, we’ll continue our search.

Если позволит погода, мы продолжим свой поиск.

Функции Participle II

Participle II в предложении может иметь следующие функции:

1. Определения. Стоит перед или чаще после определяемого существительного и переводится на русский язык причастиями на -мый, -нный, -тый, -вший(ся) (предшествовавший).

The translated book – переведенная книга.

2. Части сказуемого в страдательном залоге.

The book was translated last year.

Книга была переведена в прошлом году.

81

GRAMMAR REFERENCE

3. Обстоятельства / переводятся обстоятельственными придаточными предложениями времени, условия, причины и др. /. Перед Participle II в этой функции иногда могут стоять союзы if, unless, when.

If translated well the book will be a success.

Если книга переведена хорошо, она будет иметь успех.

4. Participle II так же, как и Participle I может быть частью самостоятельного причастного оборота.

The book translated, we shall be able to buy it.

Когда книга будет опубликована, мы сможем купить ее.

The Gerund / Герундий /

Формы и функции

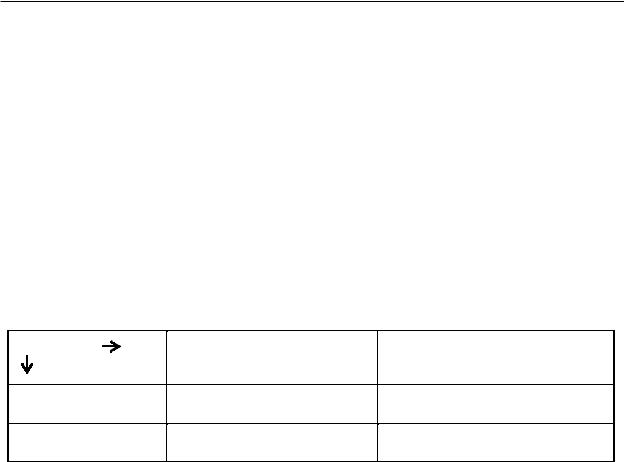

Tense Voice |

Active |

Passive |

Indefinite |

asking |

being asked |

Perfect |

having asked |

having been |

|

|

asked |

Будучи неличной формой глагола, герундий имеет категорию относительного времени и залога, может иметь прямое дополнение и определяется наречием.

Имея свойства существительного, герундий выполняет в предложении те же синтаксические функции, что и существительное: подлежащего, именной части сказуемого, дополнения, определения с предлогом и обстоятельством с предлогом. Герундий может переводиться отглагольным существительным, инфинитивом или деепричастием.

Reading English books is useful. (подлежащее) Чтение английских книг – полезно.

I like reading – Я люблю чтение (читать). (дополнение)

Примечание: После глаголов, данных ниже, в качестве прямого дополнения может стоять только герундий:

to avoid (избегать); |

to enjoy (получать удовольствие); |

to excuse (извинять(ся)); |

to intend (намереваться); |

to need (нуждаться); |

to require (требовать); |

to want (хотеть). |

|

Герундий может определяться существительным в притяжательном или общем падеже, а также притяжательным или указательным местоимением.

82

GRAMMAR REFERENCE

Такие герундиальные обороты обычно переводятся придаточным предложением, вводимым словами:

òî, ÷òî; â òîì, ÷òî; òåì, ÷òî; î òîì, ÷òî è ò.ï.

John’s returning home so late stayed unnoticed.

(То, что Джон вернулся домой так поздно, осталось незамеченным.) His returning home so late surprised nobody.

(Его возвращение домой так поздно никого не удивило.)

The Infinitive / Инфинитив /

В английском языке имеются следующие формы инфинитива:

|

Active |

Passive |

Indefinite |

to translate |

to be translated |

Continuous |

to be translating |

|

Perfect |

to have translated |

to have been translated |

Perfect |

to have been translating |

— |

Continuous |

|

|

Инфинитив является основной глагольной формой, от которой образуются все лич- ные формы глагола во всех группах времен в действительном и страдательном залогах.

Infinitive Indefinite употребляется для выражения действия, одновременного с действием, выраженным глаголом-сказуемым в личной форме в предложении.

Infinitive Continuous выражает действие в процессе его развития одновременно с действием, выраженным глаголом-сказуемым в личной форме.

Infinitive Perfect выражает действие, которое предшествует действию, выраженному глаголом-сказуемым в личной форме.

Infinitive Perfect Continuous выражает действие, продолжавшееся в течение определенного периода времени и предшествовавшее действию, выраженному глаголом-сказуе- мым в личной форме.

Форма инфинитива страдательного залога указывает на то, что действие, выраженное инфинитивом, направлено на лицо или предмет, связанный с инфинитивом.

Пример: Any mistake which is present in the calculation must be removed. Перевод: Любая ошибка, которая есть в вычислениях, должна быть удалена.

Способ перевода инфинитива на русский язык зависит от его функции в предложении. Инфинитив в английском предложении может выполнять следующие функции:

1. Подлежащего (переводится неопределенной формой глагола).

Пример: To prove this law experimentally | is very difficult. Перевод: Доказать этот закон экспериментально очень трудно.

83

GRAMMAR REFERENCE

2. Именной части составного сказуемого (переводится неопределенной формой глагола, нередко с союзом чтобы).

Пример: Your work | is to observe | the rise of inflation.

Перевод: Ваша работа заключается в том, чтобы наблюдать за повышением инфляции.

3. Части составного глагольного сказуемого после модальных глаголов и их эквивалентов и глаголов в личной форме, обозначающих начало, продолжение или конец действия.

Пример: He | is to make | the experiment. Перевод: Он должен провести этот эксперимент.

4. Дополнения (переводится неопределенной формой глагола).

Пример: He | asked | to define the unit of measurement more accurately. Перевод: Он попросил определить единицу измерения более точно.

Если дополнение выражено сложной формой инфинитива, то он переводится придаточным предложением с союзом что или чтобы.

Пример: The students were glad to have obtained such good results in the latest tests of the new model.

Перевод: Студенты были рады, что (они) достигли таких хороших результатов при последних испытаниях новой модели.

5. Обстоятельства. Инфинитив в этой функции с группой последующих слов чаще всего переводится на русский язык обстоятельством цели с союзами чтобы; для того, чтобы.

Пример: To make the price higher | we must improve the quality of goods. Перевод: Чтобы повысить цену, мы должны улучшить качество товаров.

Пример: We go to the University to study. Перевод: Мы ходим в университет, чтобы учиться.

6. Правого определения. В этой функции инфинитив с зависящими от него словами обычно переводится определительным придаточным предложением. Часто инфинитив в функции определения имеет оттенок модальности и переводится на русский язык с добавлением слов

следует, надо, должен.

Пример: Fielding | was the first | to introduce into the English novel real characters in their actual surroundings.

Перевод: Филдинг был первым, êòî ââåë в английский роман реальные характеры в их реальном окружении.

Пример: Experiments have shown that | the amount of work | to be used for producing a given amount of goods | is the same under all conditions.

Перевод: Опыты показали, что количество работы, которое нужно израсходовать для получения данного количества товаров, является одинаковым при всех условиях.

84

GRAMMAR REFERENCE

Perfect Infinitive Passive в функции определения указывает на то, что действие, выраженное инфинитивом, должно было совершиться, но не совершилось.

Пример: Another important factor to have been referred to in that article was that there are many functions of money.

Перевод: Другой важный фактор, на который нужно было бы сослаться в той статье, заключался в том, что существует много функций денег.

Если инфинитив в функции определения имеет после себя предлог, как в данном выше примере, то вся инфинитивная группа переводится определительным придаточным предложением с соответствующим предлогом перед союзным словом, а если предлог не переводится, то он придает определенный падеж этому союзному слову.

Инфинитивные обороты в английском языке

Объектный инфинитивный оборот (The Objective with the Infinitive)

Этот оборот состоит из существительного или местоимения в объектном падеже и инфинитива, между которыми существует связь аналогичная связи между подлежащим и сказуемым. Оборот в предложении стоит обычно за сказуемым основного предложения и синтаксически выполняет функцию сложного дополнения. Он употребляется после глаголов типа: to want, to suppose, to find, to expect, to believe и т.д. Оборот переводится на русский язык придаточным дополнительным предложением, причем инфинитив переводится глаго- лом-сказуемым в соответствующем времени в зависимости от формы инфинитива, а существительное или местоимение в объектом падеже – существительным или личным местоимением как подлежащее.

Пример: We know him to be the first inventor of an electrical measuring instrument. Перевод: Мы знаем, что он является первым изобретателем электрического изме-

рительного прибора.

Инфинитив в этом обороте употребляется без частицы to, если он стоит после глаголов восприятия чувств, таких как: to hear, to see, to feel, to watch и др.

Пример: We see the computer work well. Перевод: Мы видим, компьютер работает хорошо.

Субъектный инфинитивный оборот (The Nominative with the Infinitive)

Этот оборот состоит из существительного или личного местоимения в именительном падеже и инфинитива, связанного с ним по смыслу. Между ними стоит сказуемое, выраженное личной формой глагола в страдательном залоге или глаголом типа to seem, to appear в действительном залоге или оборотами to be likely, to be sure и др. Субъектный инфинитивный оборот синтаксически выполняет функцию сложного подлежащего.

85

GRAMMAR REFERENCE

Перевод всей конструкции обычно начинается со сказуемого, которое переводится неопределенно-личным предложением (известно, сообщают, кажется и т.п.). Сам оборот переводится придаточным дополнительным предложением, причем инфинитив переводится глаголом-сказуемым в соответствующем времени.

Пример: All these goods are known to be produced by our firm. Перевод: Известно, что все эти товары производятся нашей фирмой

Пример: Russian scientists and inventors are known to have discovered electrical phenomena of the greatest importance.

Перевод: Известно, что русские ученые и изобретатели открыли электрические явления величайшего значения.

86

Business Case Study

(Примеры из деловой практики)

1. Ford at Dagenham

One of the plant managers, working with his area managers at Ford’s Dagenham plant, had devised a plan for reducing costs by reorganising the work in the area of machine operation. The problem was that if the plan was to work it required two important changes from the workforce – first their co-operation in moving from the production of one set of parts to the production or another set half-way through each week. Second, it required the introduction of a new twilight shift. No extra money was on offer nor were any other inducements held out. The ‘case’ had to be sold direct to the workforce (some 80 people) by the relevant area manager. This was to be attempted at a special meeting in the old canteen at the start of the morning shift.

At the appointed hour, the workers were assembled and seated in a rather cold and uncomfortable setting, unconducive to extended debate. The shop stewards for the area were seated out at tile front. The area manager arrived ‘chauffeur-driven’ in one of the plant’s electric vehicles. Flanked by section heads he strode to the front and commenced his delivery. The style was relaxed, down-to-earth, occasionally jovial, but very direct. In essence, ‘the problem’ was explained as uncompetitive costs in the production of two power-train assemblies. The danger of at least one or these ceasing production altogether, unless the ‘uneconomic’ low volume levels could be compensated for by more flexible switching each week between one job and another was explained.

The ‘solution’ was then described. This involved the introduction of a ‘swing shift’ and the necessity for the shift, on certain days of the week, to be ready to finish the scheduled run in ‘Power Train I’ and relocate themselves to a different area of the factory to commence work on ‘Power Train II’. Questions were then invited and the area manager fielded these himself. One issue of concern was the extra time that would be needed reporting to work and in lost break time because of the distance between the two work locations. The area manager dealt with this by promising to keep it under review during the first few weeks of the new work scheme.

After about 40 minutes the area manager and the rest of the management team departed and the shop stewards were left to address the meeting. The tone was essentially a realistic one of the economics of competition and the poor state of ‘Power Train I’ because of its age and its low volumes. While some minor problems were noted with the management plan, the overall message was that rearganisation was necessary. There was very little opposition from the floor. A vote was taken and the plan was accepted almost unanimously.

(a)Identify the aspects of management that are taking place in this situation.

(b)What leadership qualities did the plant manager and the area manager demonstrate?

(c)What type of leadership style is the area manager adopting?

(d)What factors may have influenced this choice of leadership style?

(e)Use the leadership theory of Fiedler to explain why the strategy adopted by the area manager was successful.

2. Marketing the Theatre

In all branches of the theatre today, marketing expertise is crucial. When planning your strategy, the first step is to read the play which you are going to be marketing. When you know a show it is sometimes easy to find strong selling points.

87

BUSINESS CASE STUDY

Use these selling points in the design your posters and other publicity material. These must be got out in good time, at least six weeks before the show is due to open. Try to find ways to maximise local publicity about the production: does something about the play itself, or its cast perhaps, give you a key which will unlock local radio and press coverage?

It is important to think of possible group bookings – for example, you can do useful business with school coach parties when you have a play which is on the ‘A’* ) level syllabus.

There will probably be a box office revenue target (largely determined by the production cost of the play) and this will influence prices. Market research of your potential audience is useful before setting prices. The careful use of discount prices and concessions can be an important tactic.

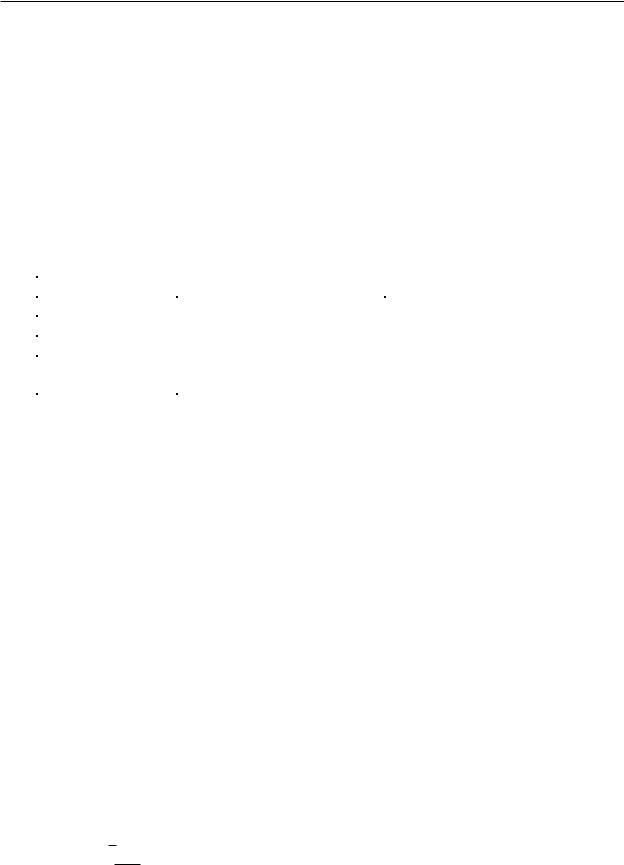

It is interesting to consider Table 1 and the range of average ticket prices charged for the different types of production and the varying extent to which use is made by box offices of discounting.

Table 1

Average Ticket Prices and the Average Discount on Ticket Prices, 1991

Type of Production |

Average Ticket |

Average Discount on |

|

Price (£) |

Ticket Price (%) |

Modern Drama |

12.59 |

10.1 |

Comedy |

13.08 |

8.5 |

Modern Musicals |

18.28 |

1.5 |

Traditional Musicals |

17.26 |

9.8 |

Revue |

15.11 |

0.7 |

Opera |

30.20 |

8.5 |

Ballet |

21.05 |

3.8 |

Classical Plays |

11.82 |

17.5 |

Children’s Shows / Pantomime |

10.79 |

4.3 |

Thrillers & Others |

13.28 |

5.5 |

At the box office, the theatre business depends, to some extent, on the custom of tourists, particularly those from the United States. However, according to the Society of London Theatres, the relative importance of tourists has been declining. While 42% of the West End audience came from overseas in 1985, this had fallen to 32% by 1991.

Theatre managers do not like having to rely on tourists because it means that there will be regular seasonal troughs in demand when the number of foreign visitors falls off in the winter. For this reason, it has been quite common for up to half a dozen shows to be forced to close during the first few months of the year.

Moreover, there are inevitably going to be bad years for tourism, for example, during periods when the Dollar is weak, or when the threat of terrorism in Europe dominates the headlines (such as in the periods after Hie Libyan bombing in 1986 and the Gulf War in 1991) and serves to discourage people from travelling abroad.

Case Study Question 1: You are the business manager of your school or college play which is to run for a week in the main hall. This means that you have the take of selling 1,000 tickets. What are the main marketing steps you must take?

Case Study Question 2: You decide to set your seat prices so that the production will ‘breakeven’. What are the main fixed and variable costs that you should expect to incur.

*) «A» – advanced – продвинутый уровень в обучении.

88

BUSINESS CASE STUDY

3. High Lane VI Form College

High Lane VI Form College acquired designated status on 1st April 1993. This meant that control for the funding of the college moved from the local authority to central government. In addition, the complete management of the budget would be carried out by the principal of the college rather than the local education authority. Finances for the college would be allocated by the Further Education Funding Council and could depend, in the main, on the number of students it could attract and on whether the college had achieved its mission statement. This is a document that set out of college’s future goals and objectives in terms of curriculum development and delivery and the pastoral programme for student guidance and support.

The principal and governors of the college decided to restructure in order to meet the challenge of the future. In the past the structure had four levels – the senior management team (the principal and two viceprincipals), senior tutors (responsible for the pastoral programme), heads of departments and main scale teachers. It was recognised that the senior management team needed to be expanded. Senior tutors were given extra responsibilities and made part of the senior management team. In addition a new team of curriculum leaders (CLs) was created. The team was made up from heads of departments in the different curriculum areas, such as the social sciences and sciences etc. and was responsible for curriculum development and delivery. Much of the success of the college would depend on how well this group worked together.

The group certainly had a variety of personalities in it – from those with new, innovative ideas to those that more concerned with administration and day to day problems. The group met formally once a fortnight to discuss issues concerning a quality curriculum. It became apparent, however, that the meetings rarely achieved concrete suggestions for future action. The meetings seemed to be used as “talking shops” for curriculum leaders to air grievances about the happenings of the week.

Some of the curriculum leaders were also part of an informal group of friends who would socialise at lunchtimes and after college. It was often at these informal gatherings / meetings that the real issues were raised and ideas discussed. Other curriculum leaders who were not at such gatherings would usually have any important issues raised communicated to them through the ‘grapevine’.

The informal meetings became a focal point for CLs to attack the lack of focus in the official meetings and also the fact that their ideas were very rarely accepted by senior management. They felt that senior management was made up of individuals who had caused a decline in the number of students by their inaction over the last five years. Their main complaint, however, was that although they had been assured by the principal that they would be the ones who would make decisions on curriculum matters, the senior management team would often intervene and veto their proposals. For example, CLs suggested that gNVQs (general national vocational qualifications) should be more fully developed in the college to attract students that had normally gone to the local FE colleges.

This idea was, rejected by the senior management team as not fitting into the academic tradition of the college. Joan, the CL for Economics and Business, felt exasperated by this decision. She said: “CLs were meant to be part of the management of the college with responsibilities for curriculum development and delivery. We meet formally and informally, communicating in a variety of ways to each other, trying to advance a common view on curriculum development. But at times we just don’t seem to have the authority to make things happen. I just don’t know what we can do”.

(a)What new formal groups did the Principal and Governors set up in April 1993?

(b)How did communication take place in formal and informal groups at High Lane?

(c)Comment on the likely effectiveness of:

(i)formal groups;

89

BUSINESS CASE STUDY

(ii) informalgroups; at High Lane.

(d)What problems might High Lane face as a result at the way group decision making is organised?

(e)Suggest 2 methods High Lane management could have used to solve the problems suggested in your answer to question (d).

4. MORE THAN JUST A LEISURE PARK

The Dome Leisure Park is Europe’s largest multi-facility leisure development under one roof, with a total floor area of 15 100 square metres. Since its opening in October 1989, it has regularly welcomed more than one million visitors through its doors per year, making it one of the UK’s top five leisure attractions, ranking it alongside Alton Towers and the Chessington World of Adventures.

The Dome is located in Doncaster, South Yorkshire. Its site gives quick and easy access to the Ml, M18, and A1 (M) motorways, thus giving good communication links to surrounding towns and cities such as Sheffield, Leeds, and Nottingham. Alternatively, the nearby mainline railway station offers rail links to London, Birmingham, Manchester, and Edinburgh.

The land on which The Dome is built and surrounding areas comprise 350 acres of council owned waste land on the Southern edge of the town, opposite the prestigious race course. The Dome can therefore be expanded without complication, or nearby land sold to other private sector investors attracted to the area.

The Aims of the Dome

The Dome was a Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council (DMBC) initiative, first conceived in 1985. It was designed, built, and opened at a cost of £25 million, which was wholly funded by the council through the receipts of sales of land.

The main objectives of The Dome are:

1.To offer the residents of Doncaster a dramatically different leisure option.

2.To position Doncaster as the focal point for leisure and tourism following the decline of the town’s more traditional industries of heavy engineering and mining.

3.To act as a catalyst for the economic and qualitative regeneration of the surrounding area and to act as an expression of confidence in the future of the community.

4.To attract investment to the town.

The Mission Statement of The Dome is:

“To enhance the quality of life of residents and visitors to Doncaster and South Yorkshire by means of a wide range of well publicised, affordable and enjoyable leisure opportunities in an attractive, healthy and safe environment”.

The Management of The Dome

The council knew that much depended on the success of The Dome, and as such, good management was imperative if they were to justify the initial cost the development demanded. They wanted the Dome to not only be a successful leisure centre, but to provide the catalyst in attracting other developers and investors to the town. In short, successful management could turn the initial £25 million into investment,

90