Advanced_Renderman_Book[torrents.ru]

.pdf

356 13 Storytelling through Lighting, a Computer Graphics Perspective

Figure 13.19 Atmosphere.

Figure 13.20 A Bug's Life-Dot running from the grasshoppers. See also color plate 13.20.

This is one reason why sometimes you can spot a model miniature; the texture doesn't properly resolve for how far away it is supposed to be.

13.4.6 Size Relationships and Position

How objects relate to each other in apparent size gives us cues about how far away they are from us. Familiar objects provide context for unfamiliar ones. In Figure 13.21 (left), we see a variety of shapes, none of which are familiar to us. We are unable to judge how big or how near any of them are to us by comparing them to each other; thus the image has no depth. In Figure 13.21 (right), we may

13.4 Creating Depth

Figure 13.21 Different shapes of all the same size create no feeling of depth (left). Various sizes of the same shape introduce depth (right).

Figure 13.22 A Bug's Life --This image is staged to remind the viewer of the true scale of tiny insects in the huge world. (© Disney Enterprises, Inc. and Pixar Animation Studios.) See also color plate 13.22.

not necessarily be familiar with the size of any particular square, but the repeating shapes tempt us to think that perhaps all of the squares are the same size at various distances away from us. By repeating the shape, we gain some familiarity with it The illusion of forced perspective often includes this technique.

Usually the eye expects large objects that are large in frame to be nearer that the small objects. When we were working on A Bug's Life, we realized early on that the characters were small in an enormous world. We occasionally designed a shot to reinforce this normal indicator of scale and perspective (Figure 13.22) We also found that reversing common perspective also helped to drive home out disparity in scale, especially when the distant elements are visibly much larger tha the foreground elements in the frame (Figure 13.23).

An object's size and position within the image frame imply depth. In Figure 13.2 (left), we have a large square on the left and a small one on the right. The right

358 13 Storytelling through Lighting, a Computer Graphics Perspective

Figure 13.23 A Bug's Life --This image emphasizes scale on the insect's level. (© Disney Enterprises, Inc. and Pixar Animation Studios.) See also color plate 13.23.

Figure 13.24 Object position in the frame can imply depth or size.

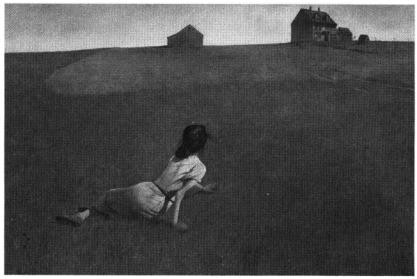

one tends to appear smaller rather than farther away because it has the same vertical position in the frame. When we move the smaller one up in the frame (Figure 13.24, right), it appears farther away rather than simply smaller. In Andrew Wyeth's painting of Christina's World (Figure 13.25), this visual cue is necessary to make the illusion of depth work, since it doesn't have the benefit of other cues such as aerial or linear perspective. Christina would look like a giant, or the house and barn would look like toys, if they were all on the same level in the frame.

13.4.7 Overlap

If object A occludes object B by overlapping it, then object A is decidedly nearer. This depth comparison is not at all subjective. An image that has minimal overlap will appear more flat than an image that contains many overlapping shapes.

359

13.4 Creating Depth

Figure 13.25 In Andrew Wyeth's Christina's World, size and position of objects create depth. (Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.)

13.4.8 Volume

An object that is lit to maximize its volume will increase the impression of depth because it appears to occupy more space than an object that is flatly lit. Compare the two images in Figure 13.26. Both are the same geometry, but one is lit to showcase the volumetric form while the other is lit to minimize it. The orange on the right is lit with very soft frontal lighting, which tends to reduce texture and volume. The orange on the left was lit from a three-quarter position with a harder light to enhance the roundness of the form and to emphasize texture.

13.4.9 Planes of Light

Most literature on live-action lighting discusses the necessity of creating planes of light, often without really explaining what that means or how to achieve it. In its simplest form, a lighting plane is essentially a collection of objects or subjects that are parallel to the camera plane and are lit as a unit to contrast with other planes. These planes can be any distance from the camera and are defined with light for the purpose of creating the illusion of depth through overlapping layers. The illusion created is limited, however, because the planes themselves mirror the image plane. Simple planes of light can be used to visually simplify and organize a busy scene (see Figure 13.27).

360 13 Storytelling through Lighting, a Computer Graphics Perspective

Figure 13.26 Rendered example of orange roundly lit (left) and flatly lit (right).

Figure 13.27 An example of simple planes of light in William Joyce's Dinosaur Bob and His Adventures with the Family Lazardo. (© Copyright ) 1998, 7 995 by William Joyce. Used with permission of HarperCollins Publishers.)

361

13.4 Creating Depth

Figure 13.28 Rendered example showing objects lit as planes of light.

In its more complicated form, objects can be lit in relationship to other objects to enhance the illusion of space. Not only is the form lit to enhance its volume, illumination and form are carefully placed so that the lights and darks create small planes within the image. In Figure 13.28 notice how each bright area is staged over a dark area and vice versa.

13.4.10 Depth of Field

Depth of field is an inherent feature of binocular eyesight, hence it feels natural in a monocular camera lens. With a live-action camera, depth of field is determined by the focal length of the lens as well as the aperture used. Each lens has its limits within which it can operate effectively. With these limits in mind, a lens is chosen depending on the story point, mood, film stock, available lighting intensity, the actor's features, and compositional reasons. The choice is a technical decision as well as an artistic one. A synthetic camera has the technical restrictions removed, which makes the choice a purely aesthetic one. This doesn't mean that the choice becomes any easier. The lens focal length can determine how the viewer interacts with the subject. Two close-ups with similar subject framing can have dissimilar effects resulting from the perspective and focal depth caused by the choice of lens. One lens can place the viewer uncomfortably close to the subject, and the other places the viewer at a more detached distance simply through depth of field. A close-up where the background is out of focus will feel more intimate than one where the background is sharp.

362 13 Storytelling through Lighting, a Computer Graphics Perspective

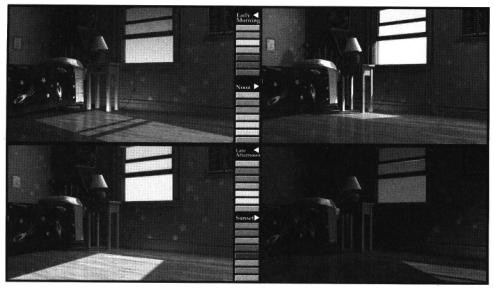

Figure 13.29 Toy Story 2-Andy's room at four different times of day, and the light color palettes for each setting. (© Disney Enterprises, Inc. and Pixar Animation Studios.) See also color plate 13.29.

13.5 Conveying Time of Day and Season

Conveying the time of day and season is important to place the story setting and to illustrate passages of time. It is also a major factor in determining the quality, quantity, motivation, direction, and color of light sources for a scene; as a result, it is also a major component in setting the mood.

Morning feels optimistic and cheerful. The day is beginning with high hopes for what it will bring. The air is fresh and you feel rested and rejuvenated. Midday is energetic and the time for getting things done. Evening is romantic, but it is also a little melancholy. The day is coming to an end, slowing down, and you are getting tired. Night is lonely and pessimistic, which is why we tend to "sleep on our problems" because they do not seem so bad the next morning. These daily cycles are repeated on a yearly scale as well; spring is a new beginning, the summers are for getting work done, autumn is the time for reflecting and taking stock, and winter is for hibernating, dormancy, and even death.

The angle and color of the light, as well as the length and color of the shadows, provide the viewer much information about the time of day. In the four examples in Figure 13.29, we see Andy's room from Toy Story 2 at four different times of day: early morning, noon, late afternoon, and at sunset. The figure also shows the light color palettes for each setting.

363

13.6 Enhancing Mood, Atmosphere, and Drama

13.6 Enhancing Mood, Atmosphere, and Drama

Many aspects of an image affect its mood and dramatic qualities. The sets, the costumes, the actors and their acting, the staging, the score, the weather, and the time of day are all components that can illustrate the mood of the story being told. There are also other aspects that may not be as obvious: basic shape, rhythm, balance, value, and color, as well as the style and motivation of the lighting.

13.6.1Shape

The computer animation environment is 3D as it exists within the computer. Threedimensional objects move and deform freely, changing shape and position, in their 3D world. And although the sculptural form and motion of the objects affect how light is reflected and shadows are cast, ultimately, it is the placement and definition of the resulting 2D shapes, within the image frame, that become the final product. Camera placement and lighting are what control this transition from the original design space to the image the audience sees projected on the screen.

Shapes supply an important emotional role within a visual structure. All shapes are based upon three simple primitives: a square, a circle, or a triangle. Each has its own inherent personality. A square is stable and solid, and implies no motion or direction. A circle is benign and friendly, also implying no motion or direction. The diagonal edges of a triangle make it an energetic and dynamic shape. Horizontal shapes imply stability, vertical lines imply potential motion, and diagonal lines imply dynamic motion and depth. When working within the rectangular cinema format, horizontal and vertical lines work as stabilizers and reduce feelings of movement because they mirror the format boundaries; thus a common camera technique to introduce a feeling of instability is to roll the camera.

A composition is primarily an arrangement of shapes. The brain not only strives to recognize shapes, it also attempts to organize them into figure and ground relationships, or positive and negative space. This happens on several levels. Just as the brain distinguishes between background and foreground planes, it also looks for positive and negative relationships within each plane. The focal points and busy areas of the plane become the positive space, while the other areas become relief for the eye, or negative space. Negative spaces are not necessarily empty flat areas, but they do not tend to attract attention. In a finely crafted image, as much care is given to the shape and placement of the negative spaces as is given to the subject itself.

A lighting designer is constantly balancing the need for readability and the need for integration. An image that has all of its shapes clearly defined is easy to understand. However, it is not as interesting as an image where shapes fall in and out of definition, by falling in and out of light and shadow. Similarly, clear definition between foreground/background and positive/negative space is easy to read but is

364 13 Storytelling through Lighting, a Computer Graphics Perspective

Figure 1 3.30 Tin Toy-An example of distortion. (© Pixar Animation Studios.)

not a particularly interesting spatial solution. It is often desirable to blend together, or integrate, the spaces in some way to avoid the harsh juxtaposition of forms, as is evident in a bad matte. The use of a similar color or value along an edge can help the eye travel more easily between the spaces. The brain is very good at recognizing shapes with a minimal amount of information, especially if this shape is already familiar to the viewer. By just hinting at a shape with a minimal amount of light, the viewer's imagination becomes engaged, and a mood of mystery and suspense is evoked.

Shape distortion can be a powerful emotional tool. The viewer is so accustomed to seeing the world in a natural fashion that when shape is distorted in an image, it signals an altered state of reality. An emotional response will range widely depending on the shape being distorted and its context. The baby in Tin Toy is distorted, using refraction through a cellophane wrapper, with comic relief to the plight of Tinny (Figure 13.30). In another context the same technique may be eerie and unsettling. The individual parts of the mutant toys in Toy Story are not themselves distorted, but in combination they represent a distorted vision of a lifelike toy. The combined effect is disturbing and repulsive, which helps us believe that they may indeed be cannibals. Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo has many nice examples of using the camera to dynamically distort the environment to create an emotional response.

365

13.6 Enhancing Mood, Atmosphere, and Drama

Figure 13.31 Degas' Millinery Shop illustrates repetition of shape. (Photograph courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.)

13.6.2 Repetition and Rhythm

The use of similarly shaped or colored elements in an image, however subtle, is a strongly unifying force, as the Gestalt grouping principle indicates. Repetition is an aspect of visual unity that is exhibited in some manner in every image. The human eye is very good at making comparisons and correcting minor differences to equate two shapes as being essentially the same. This comparison process is very dynamic as the eye jumps from one shape to another. In the Degas image (Figure 13.31), we immediately recognize the hat shapes and visually equate them. Our eye moves from one hat to the next in a circular manner around the image.

A shape or line that is repeated once has special properties. As the eye pingpongs between the two elements, it creates a visual channel that contains the eye and directs attention to anything that happens to be within it.

A small number of repeated or similar elements become visually grouped together to form a unit. To cross the boundary from simple repetition to rhythm, a larger number of elements is required, enough elements so as to discourage grouping as a single unit, but instead several units. Groupings of three or more start to