мошонка, мочевой пузырь уретра

.pdf

182 ULTRASOUND: THE REQUISITES

A B

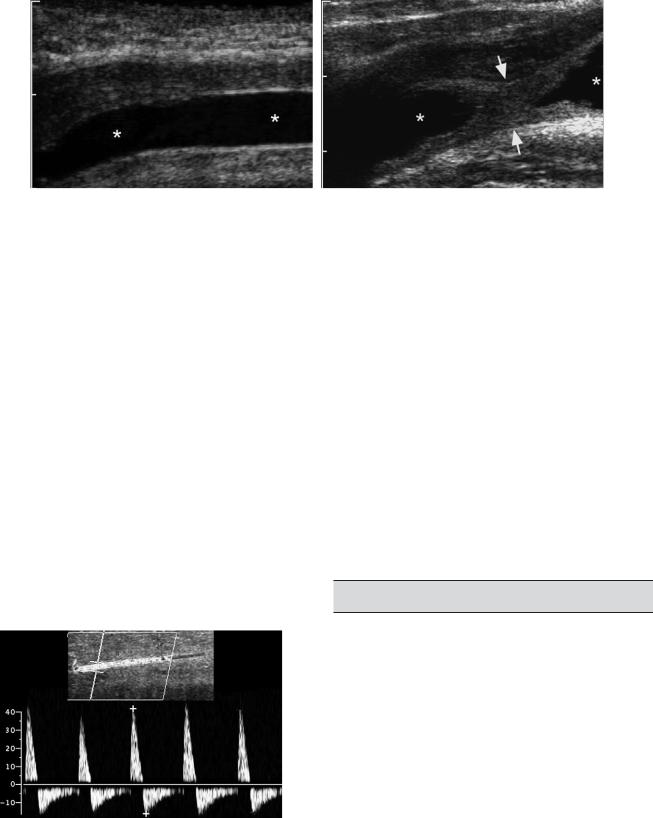

Figure 6-50 Urethral stricture in a man. A, Longitudinal view of the anterior urethra during injection of saline shows a normal uniform urethral lumen (*). B, Longitudinal view of the posterior urethra shows a localized stricture (arrows) with a normal urethral lumen both proximal and distal (*).

between 25 and 35 cm/sec are indeterminate. In addition, as the venous outflow mechanism starts to prevent outflow of blood from the corpora cavernosa, diastolic arterial inflow starts to drop and may even reverse. This can be quantified by measuring the arterial resistive index. If arterial inflow is adequate and the resistive index stays below 0.8 for 15 to 20 minutes after the injection, venous leak should be suspected.

Priapism is another condition that can be evaluated with Doppler. This is done primarily to search for an occult arteriovenous fistula (high-flow priapism), which occurs most often in patients with a history of penile or perineal trauma, or thrombosis of the dorsal penile vein (low-flow priapism).

Peyronie’s disease is fibrosis of the tunica albuginea of the corpora cavernosa. It is an idiopathic condition that typically affects men older than 45 years old. Lack of

Figure 6-51 Normal penile Doppler study. Color Doppler and pulse Doppler waveform from the cavernosal artery after injection of prostaglandin E shows a high resistance waveform with a systolic velocity slightly greater than 40 cm/sec. Diastolic flow reversal indicates intact venous outflow mechanism.

expansion of the tunica albuginea in the area of fibrosis causes the penis to bend toward the plaque during erection. The associated pain and penile curvature can make intercourse impossible. On physical examination, an area of thickening corresponding to the plaque is typically palpable. On sonography, the plaques appear as a localized area of thickening of the tunica albuginea, often with calcification (Fig. 6-52). The typical location is along the dorsum of the penis near the base, but it can also involve other areas.

Penile masses can occasionally be evaluated with sonography. As in the testes, soft tissue masses with internal blood flow should raise the suspicion of a tumor (Fig. 6-53). Lesions with no flow or lesions that are cystic are less likely to be neoplastic.

PROSTATE

Prostate cancer is the most common malignant tumor and is the second most common cause of cancer-related mortality in men. It is most common in blacks, less common in whites, and uncommon in Asians. As many as 50% of men in their 50s and 80% of men in their 80s will have at least microscopic foci of prostate cancer. Despite the relatively ubiquitous nature of prostate cancer in elderly men, there is only a 5% to 10% chance of their exhibiting symptoms from the disease. Therefore, most of these cancers are clinically occult.

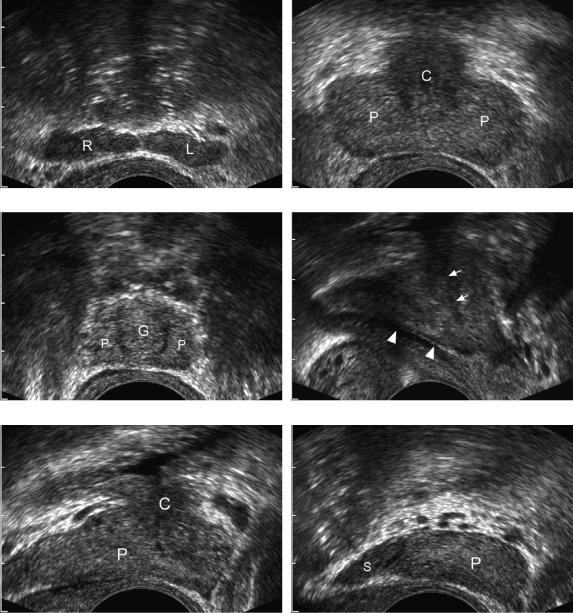

The prostate is composed of four zones. In the normal gland, the peripheral zone is the largest. It is located posteriorly and extends to both lateral margins (Fig. 6-54). It becomes thicker in the apex (inferior aspect of the gland) and thinner in the base (superior aspect of the gland). Approximately 70% of the cases of prostate cancer occur in the peripheral zone. The central zone is the next largest

Lower Genitourinary |

183 |

A B

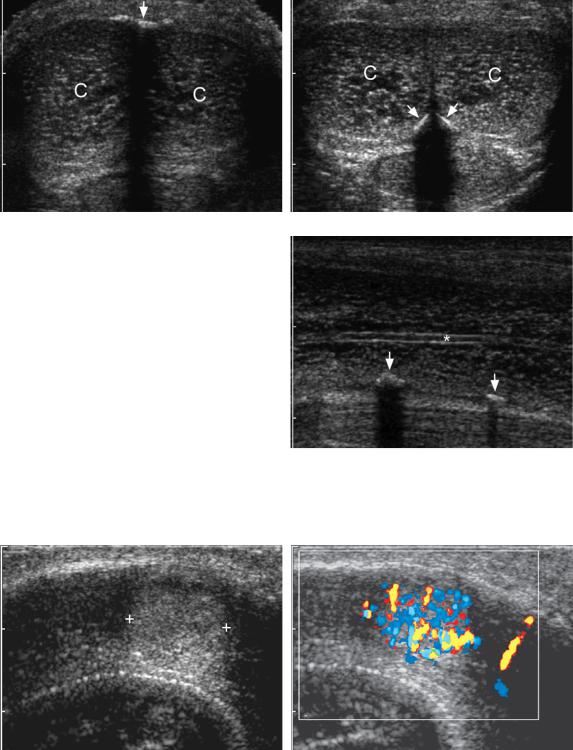

Figure 6-52 Peyronie’s disease. A, Transverse view of the penis shows the right and left corpora cavernosa

(C) and a calcified shadowing plaque (arrow) in the midline along the dorsal surface. B, Transverse view in the same patient shows additional plaques (arrows) along the ventral surface. C, Longitudinal view of the right corpora cavernosa shows the cavernosal artery (*) centrally and calcified plaques (arrows) along the ventral surface.

C

A B

Figure 6-53 Penile metastasis from renal cell carcinoma. A, Longitudinal gray-scale view of the base of the penis shows a hyperechoic solid mass (cursors) within the corpora cavernosa. B, Color Doppler view shows marked hypervascularity within the mass. This was the only identified site of metastasis in this patient with a history of renal cell carcinoma.

184 ULTRASOUND: THE REQUISITES

A B

C D

E F

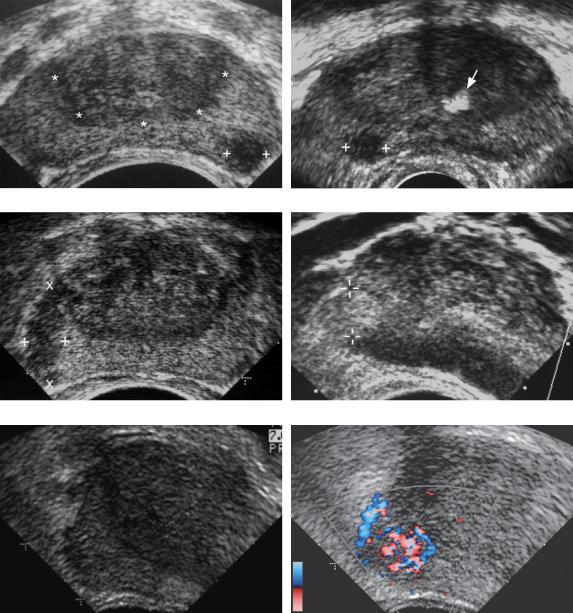

Figure 6-54 Normal prostate. A, Transverse view through the level of the seminal vesicles shows the hypoechoic oblong symmetric-appearing solid right (R) and left (L) seminal vesicles. B, Transverse scan through the base (superior aspect) of the prostate shows the slightly hyperechoic peripheral zone (P) and the slightly less echogenic central gland (C). C, Transverse view at the apex (inferior aspect) of the prostate shows the inferior aspect of the peripheral zone (P) and the periurethral glandular area (G). D, Midline sagittal view shows the ejaculatory duct (arrowheads) and the proximal urethra (arrows). E, Sagittal view just lateral to the midline shows mostly peripheral zone (P) and a smaller central gland (C). F, Sagittal view through the lateral aspect of the prostate shows peripheral zone (P) and the seminal vesicle (S).

zone and is positioned immediately deep to the peripheral zone. It is located predominantly in the base (see Fig. 6-54). Five percent of the cases of cancer are located in the central zone. The transitional zone is located in the periurethral region between the base and apex. It is the smallest zone in the normal gland, but because benign prostatic hypertrophy arises in the transitional zone, it is rarely seen in its normal state. Twenty percent of the cases of cancer occur in the transitional zone. The anterior aspect of the prostate is composed of nonglandular tissue and is called the fibromuscular stroma. The seminal vesicles are bilaterally symmetric structures situated immediately above the prostate. They are bulbous laterally and taper medially (see Fig. 6-54). (See Table 6-3 for a summary of the characteristics of prostate cancer.)

The primary role of sonography in evaluation of the prostate is to guide biopsies. With modern transrectal transducers it is very easy to direct core biopsy needles into a specified area of the prostate. When focal lesions are visualized sonographically or palpated on rectal examinations, they should be sampled and random biopsy specimens from at least all four quadrants should be obtained. These random biopsy specimens are very important because cancer is found in up to 20% of such cases. If the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level is elevated, then random biopsy specimens should be obtained even when there are no focal lesions.

It was originally hoped that transrectal sonography would be sensitive enough at detecting prostate carcinoma to serve as a screening test. Unfortunately, its sensitivity is only 60% to 70% at best. In addition, the specificity of sonography is not such that a focal lesion of any type can be assumed to be a cancer. Therefore, there is very little reason to perform prostate sonography without performing prostate biopsies at the same time.

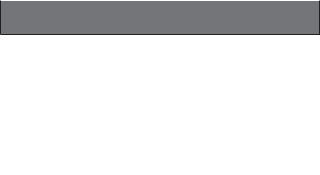

The sonographic appearance of prostate cancer varies, but 70% are hypoechoic with respect to the peripheral zone (Fig. 6-55A to C). The remainder that

Table 6-3 Characteristics of Prostate Cancer

Characteristic |

Frequency |

|

|

Location |

|

Peripheral zone |

75% |

Transitional zone |

20% |

Central zone |

5% |

Echogenicity |

|

Hypoechoic |

70% |

Hyperechoic/mixed |

30% |

|

|

Lower Genitourinary |

185 |

can be seen with ultrasound are hyperechoic (see Fig. 6-55D) or mixed. Cancer may appear either as a discrete nodule or as an infiltrative hypoechoic region (see Fig. 6-55C). Cystic cancer is very rare. Although the classic appearance of prostate cancer is that of a hypoechoic nodule in the peripheral zone, only 20% to 30% of such nodules are actually cancers. The rest are benign conditions such as prostatitis, atrophy, fibrosis, infarct, and benign prostatic hyperplasia (Fig. 6-56). Most prostate cancers appear hypervascular on color Doppler analysis, and in a limited number of cases the hypervascularity is detectable even when a focal nodule is not seen on gray-scale studies (see Fig. 6-55E and F).

The American Cancer Society currently recommends that screening for prostate cancer consist of both the digital rectal examination and determination of the PSA level. This should be started at age 50, unless the patient is at high risk (African American or strong family history). The PSA level is considered normal if it is 0 to

4 ng/mL, borderline if it is 4 to 10 ng/ml, and abnormal if it exceeds 10 ng/ml. Besides prostate cancer, benign prostatic hypertrophy, prostatitis, and prostate infarcts can also cause the PSA level to be elevated. On the other hand, not all patients with prostate cancer have abnormal PSA levels. Additional factors that are helpful in determining the significance of the PSA value are the age of the patient, the degree of benign prostatic hypertrophy, and the rate of change from one determination to the next. Elevated or borderline levels are more worrisome in young men, men without significant benign prostatic hypertrophy, and men who have had previously normal levels.

Benign prostatic hypertrophy involves the transitional zone and produces enlargement, inhomogeneity, calcification, and occasionally cystic changes. These changes make it very difficult to detect cancer in the transitional zone.

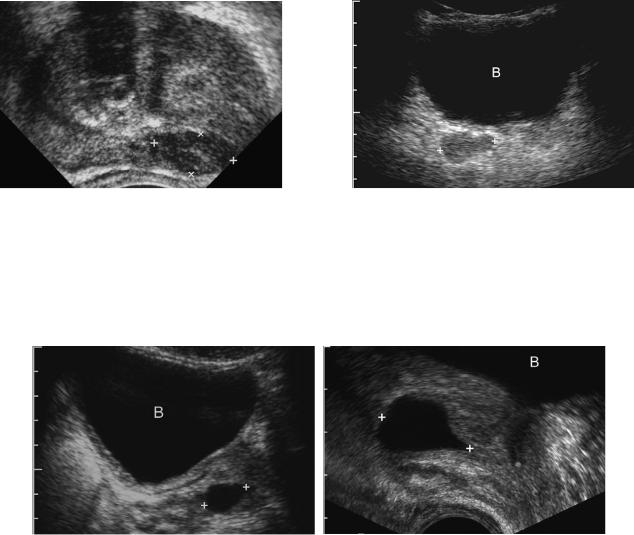

Prostatic cysts are occasionally encountered and can occur from a variety of causes. Cysts that arise in or near the midline of the prostatic base include utricle cysts, müllerian duct cysts, and ejaculatory duct cysts (Fig. 6-57). They are difficult to differentiate with sonography alone, although ultrasound-guided aspiration of the cyst will reveal spermatozoa only in ejaculatory duct cysts. Cysts may also arise as the result of obstruction of the seminal vesicle. Retention cysts can occur anywhere in the prostate. Cystic changes can also occur in the settings of prostatitis and benign prostatic hypertrophy.

Seminal vesicle cysts and agenesis are rare anomalies that are occasionally encountered during sonography of the bladder or prostate (Fig. 6-58). Both are associated with other genitourinary anomalies, especially renal agenesis and agenesis of the vas deferens.

186 ULTRASOUND: THE REQUISITES

A B

C D

E F

Figure 6-55 Prostate cancer in different patients. A, Transverse view through the mid gland shows a focal hypoechoic solid nodule in the left peripheral zone (cursors). The demarcation between the central gland and the peripheral zone (*) is well illustrated in this prostate. B, Transverse view through the mid gland shows a peripheral hypoechoic solid nodule in the right side of the prostate (cursors). A focus of calcification (arrow) is seen in the central gland. (Case courtesy of Steve Winn, Maine Medical Center.) C, Transverse view through the mid gland shows an infiltrative region of decreased echogenicity in the right peripheral zone (cursors). D, A transverse view through the right side of the prostate shows a solid hyperechoic nodule in the peripheral zone (cursors). This is an unusual appearance for prostate cancer. E and F, Transverse gray-scale (E) and color Doppler (F) views of the right side of the prostate show a focal area of hypervascularity (cursors) in the peripheral zone that was biopsy proven to represent prostate cancer. Because this cancer was isoechoic, no abnormality was identified in this region on gray-scale imaging.

Lower Genitourinary |

187 |

Figure 6-56 Benign nodule. Transverse view of the prostate shows a hypoechoic nodule (cursors) in the left peripheral zone. Some calcification is noted in the central zone. Biopsy showed no evidence of malignancy in the region of the focal peripheral zone nodule.

Figure 6-58 Agenesis of the seminal vesicle. Transverse transabdominal view of the pelvis through the filled urinary bladder (B) shows a normal-appearing right seminal vesicle (cursors). No left seminal vesicle is identified. This patient also had congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens.

A B

Figure 6-57 Prostatic utricle cyst. A, Transabdominal view through the filled urinary bladder (B) shows an ovoid cyst in the midline of the prostate (cursors). B, Midline transrectal view in another patient shows a teardrop-shaped cyst in the superior aspect of the prostate (cursors). The bladder

(B) is seen superiorly.

188 |

ULTRASOUND: THE REQUISITES |

|

|

|

|

Key Features |

|

|

|

|

|

The most important characteristics of a scrotal mass |

follow-up sonograms have a very low yield and are |

|

|

from the standpoint of determining its neoplastic vs. |

probably not warranted. |

|

non-neoplastic nature is its location (intratesticular |

Testicular torsion may appear normal on gray-scale |

|

vs. extratesticular), tissue characteristics (cystic vs. |

imaging. Detectable gray-scale abnormalities seen in |

|

solid/mixed), vascularity (detectable vs. nondetect- |

some patients include an enlarged hypoechoic testis, |

|

able), and physical examination findings (palpable vs. |

a torsion knot, a reactive hydrocele, and scrotal wall |

|

nonpalpable). |

thickening. The diagnosis is made by detecting |

Seminomas are usually hypoechoic and homogeneous. |

decreased or absent blood flow to the testis. |

|

Nonseminomatous germ cell tumors are usually |

Epididymitis and orchitis can produce an enlarged, |

|

|

heterogeneous and frequently have cystic |

hypoechoic, and hypervascular epididymis and testis. |

|

components and calcifications. |

Epididymitis is frequently focal. Orchitis is usually |

The most common scrotal mass is the spermatocele. |

diffuse. |

|

Most hydroceles, especially large ones, are idiopathic. |

Bladder cancer and blood clots can be distinguished by |

|

|

Hydroceles also occur with tumors, torsion, |

looking for mobility and detectable vascularity. |

|

inflammatory disorders, and trauma. |

Transvaginal and transperineal sonography are effective |

Varicoceles are very common and appear as enlarged, |

ways to evaluate women with suspected urethral |

|

|

multiple, tortuous veins in the peritesticular region. |

diverticula and periurethral abnormalities. |

|

Eighty-five percent are on the left, and 15% are |

Normal penile Doppler should have a deep cavernosal |

|

bilateral. Isolated right varicoceles are rare. |

velocity that exceeds 35 cm/sec after injection of a |

Epidermoid cysts typically have peripheral calcification |

vasoactive substance. |

|

|

or an “onion peel” appearance. |

Peyronie’s disease causes plaque formation in the tunica |

The testis can act as a sanctuary site for lymphoma and |

albuginea of the corpora cavernosa. |

|

|

leukemia. |

The main role of prostate sonography is to help guide |

Testicular microlithiasis is seen in many patients with |

transrectal prostate biopsies. Screening for prostate |

|

|

germ cell tumors. Isolated microlithiasis likely |

cancer currently consists of measuring the PSA levels |

|

increases the risk of germ cell tumors but only |

and digital rectal examinations. |

|

minimally. Patients with isolated microlithiasis |

Seventy percent of prostate cancers are hypoechoic and |

|

should have annual physical examinations and |

located in the peripheral zone. |

|

perform periodic self-examinations. Repeated |

|

|

|

|

SUGGESTED READINGS

Atkinson GO Jr, et al: The normal and abnormal scrotum in children: Evaluation with color Doppler sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 158:613, 1992.

Backus ML, Mack LA, Middleton WD, et al: Testicular microlithiasis: Imaging appearances and pathologic correlation. Radiology 192:781-785, 1994.

Balconi G, Angeli E, Nessi R, et al: Ultrasonographic evaluation of Peyronie’s disease. Urol Radiol 10:85-88, 1988.

Bennett HF, Middleton WD, Bullock AF, Teefey SA: Sonographic follow-up of patients with testicular microlithiasis. Radiology 218:359-363, 2001.

Berman LH, Bearcroft PW, Spector S: Ultrasound of the male anterior urethra. Ultrasound Q 18:123-133, 2002.

Brown DL, et al: Cystic testicular mass caused by dilated rete testis: Sonographic findings in 31 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 158:1257, 1992.

Burks DD, et al: Suspected testicular torsion and ischemia: Evaluation with color Doppler sonography. Radiology 175:815, 1990.

Cannon ML, Finger MJ, Bulas DI: Case report: Manual testicular detorsion aided by color Doppler ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med 14:407-409, 1995.

Cass AS, Cass BP, Veeraraghavan K: Immediate exploration of the unilateral acute scrotum in young male subjects. J Urol 124:829, 1980.

Catalona WJ, et al: Measurement of prostate-specific antigen in serum as a screening test for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 324:1156, 1991.

Cheng S, Rifkin MD: Color Doppler imaging of the prostate: Important adjunct to endorectal ultrasound of the prostate in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Ultrasound Q 17:185-189, 2001.

Choyke PL: Imaging of prostate cancer. Abdom Imaging 20:505-515, 1995.

Dubin L, Amelar RD: Varicocele. Urol Clin North Am 5:563, 1978.

Dyke CH, Toi A, Sweet JM: Value of random US-guided transrectal prostate biopsy. Radiology 176:345, 1990.

Eskey CJ, et al: Malignant lymphoma of the testis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 169:822.

Fournier GR Jr, et al: High resolution scrotal ultrasonography: A highly sensitive but nonspecific diagnostic technique. J Urol 134:490, 1985.

Frauscher F, Klauser A, Halpern EJ: Advances in ultrasound for the detection of prostate cancer. Ultrasound Q 18: 135-142, 2002.

Gooding GAW, Leonhardt W, Stein R: Testicular cysts: US findings. Radiology 163:537, 1987.

Gooding GAW, et al. Cholesterol crystals in hydroceles: Sonographic detection and possible significance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 169:527-529, 1997.

Gordon LM, et al. Traumatic epididymitis: Evaluation with color Doppler sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 166: 1323-1325, 1996.

Halpern EJ, Frauscher F, Strup SE, et al: Prostate: highfrequency Doppler US imaging for cancer detection. Radiology 225:71-77, 2002.

Hamm B, Fobbe F, Loy V: Testicular cysts: Differentiation with US and clinical findings. Radiology 168:19, 1988.

Hamper UM, et al: Cystic lesions of the prostate gland: A sono- graphic-pathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med 9: 395, 1990.

Horstman WG, et al: Color Doppler US of the scrotum. Radiographics 11:941, 1991.

Horstman WG, et al: Testicular tumors: Findings with color Doppler US. Radiology 185:733, 1992.

Horstman WG, Haluszka MM, Burkhard TB: Management of testicular masses incidentally discovered by ultrasound. J Urol 151:1263-1265, 1994.

Horstman WG, Middleton WD, Melson GL: Scrotal inflammatory disease: Color Doppler US findings. Radiology 179:55, 1991.

Horstman WG: Scrotal imaging. Urol Clin North Am 24: 653-671, 1997.

Karcnik TJ, Simmons MZ, Abujudea HA: Ultrasound imaging of the adult urinary bladder. Ultrasound Q 15:135-147, 1999.

Kaye KW, Richter L: Ultrasonographic anatomy of the normal prostate gland: reconstruction by computer graphics. Urology 35:12-17, 1990.

Kuligowska E, Barish MA, Fenlon HM, Blake M: Predictors of prostate carcinoma: Accuracy of gray-scale and color Doppler US and serum markers. Radiology 220:757-764, 2001.

Lerner RM, et al: Color Doppler US in the evaluation of acute scrotal disease. Radiology 176:355, 1990.

Leung ML, Gooding GA, Williams RD: High-resolution sonography of scrotal contents in asymptomatic subjects. AJR Am J Roentgenol 143:161, 1984.

Marsman JW: Clinical versus subclinical varicocele: Venographic findings and improvement of fertility after embolization. Radiology 155:635, 1985.

Martinez-Berganza MT, Sarria L, Cozcolluela R, et al: Cysts of the tunica albuginea: Sonographic appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 170:183-185, 1998.

Lower Genitourinary |

189 |

Middleton WD, et al: Acute scrotal disorders: Prospective comparison of color Doppler US and testicular scintigraphy. Radiology 177:177, 1990.

Middleton WD, Bell MW: Analysis of intratesticular arterial anatomy with emphasis on transmediastinal arteries. Radiology 189:157, 1993.

Middleton WD, Melson GL: Testicular ischemia: Color Doppler sonographic findings in five patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 152:1237, 1989.

Middleton WD, Middleton MA, Dierks M, et al: Sonographic prediction of viability in testicular torsion. J Ultrasound Med 16:23-27, 1997.

Middleton WD, Thorne DA, Melson GL: Color Doppler ultrasound of the normal testis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 152:293, 1989.

Middleton WD, Teefey SA, Santillan C: Testicular microlithiasis: Prospective analysis of prevalence and associated tumor. Radiology 224:425-428, 2002.

Moghe PK, Brady AP: Ultrasound of testicular epidermoid cysts. Br J Radiol 72:942-945, 1999.

Morey AF, McAninch JW: Ultrasound evaluation of the male urethra for assessment of urethral stricture. J Clin Ultrasound 24:473-479, 1996.

Morey AF, McAninch JW: Sonographic staging of anterior urethral strictures. J Urol 163:1070-1075, 2000.

Ngheim HT, Kellman GM, Sandberg SA, Craig BM: Cystic lesions of the prostate. Radiographics 10:635-650, 1990.

Nghiem HT, et al: Cystic lesions of the prostate. Radiographics 10:635, 1990.

Pavlica P, Barozzi L: Ultrasound of penile tumors and trauma. Ultrasound Q 14:95-109, 1998.

Phillips G, Kumari-Subaiya S, Sawitsky A: Ultrasonic evaluation of the scrotum in lymphoproliferative disease. J Ultrasound Med 6:169, 1987.

Rifkin MD, et al: Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography in staging early prostate cancer: Results of a multi-institutional cooperative trial. N Engl J Med 323:621, 1990.

Rifkin MD, McGlynn ET, Choi H: Echogenicity of prostate cancer correlated with histologic grade and stromal fibrosis: Endorectal US studies. Radiology 170:549, 1989.

Rifkin MD: Biopsy techniques of the prostate. Ultrasound Q 15:162-183, 1999.

Schwerk WB, Schwerk WN, Rodeck G: Testicular tumors: Prospective analysis of real-time US patterns and abdominal staging. Radiology 164:369, 1987.

Shawker TH, et al: Intratesticular masses associated with abnormally functioning adrenal glands. J Clin Ultrasound 2:51-58, 1992.

Siegel C, Middleton WD, Teefey SA, et al: Sonography of the female urethra. AJR Am J Roentgenol 170:1269-1272, 1998.

Silverberg E: Cancer in young adults (ages 15 to 34). CA Cancer J Clin 32:32, 1982.

190 ULTRASOUND: THE REQUISITES

Steinfeld AD: Testicular germ cell tumors: Review of contemporary evaluation and management. Radiology 175:603, 1990.

Tackett RE, et al: High resolution sonography in diagnosing testicular neoplasms: Clinical significance of false positive scans. J Urol 135:494, 1986.

Thornbury JR, Ornstein DK, Choyke PL, et al: Review: Prostate cancer: What is the future role for imaging? AJR Am J Roentgenol 176:17-22, 2001.

Weingarten BJ, Kellman GM, Middleton WD, Gross ML: Tubular ectasia within the mediastinum testis. J Ultrasound Med 11:349-353, 1992.

Williamson RC: Torsion of the testis and allied conditions. Br J Surg 63:465, 1976.

Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, O’Donoghue MJ, Green DE: Tumors and tumorlike lesions of the testis: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 22:189-216, 2002.

Wong-You-Cheong JJ, Wagner BJ, Davis CJ Jr: From the Archives of the AFIP: Transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary tract: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 18: 123-142, 1998.