2.3 Diffusion of the Internet and low inflation in the information economy

It is a well-established view that investments in information and communication technologies (ICTs) have a positive impact on productivity. Whereas this relation has been absent for many years, leading to a vast literature on the so-called Solow paradox, the developments in the last decade, especially in the US, led many authors to conclude that ICT investment indeed pay off. There is even some evidence that investments in ICTs lead to positive network externalities such that productivity gains are larger than anticipated by investors and are larger for larger networks in which firms operate. Apart from boosting productivity, the Information Economy, or new economy, shows a remarkable relation between inflation and unemployment.

There is ample evidence that the non-accelerating-inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) has been fallen in the last decade. Several reasons are addressed in the literature. Ball and Moffitt (2001a,b), Ball and Mankiw (2002), among others, show evidence that wage rates adopt slowly to changes in productivity such that a boost in productivity is not immediately followed by an increase in wage rates such that total wage costs fall.3 This effect explains both the rise in the NAIRU in the 1970s, a period characterized by the productivity slowdown where growth in wage rates did not adopt to the fall in productivity growth as a result of which the NAIRU rose, as well as the more recent opposite developments.

Firms producing final output are assumed to operate in a number of independent sub-markets. The focus of this paper is on one specific sub-market in which n-firms are active. In the initial situation, all transactions between these firms and the intermediate goods producing sectors run through traditional channels, i.e. ordering goods, billing, exchange of information etc. is done in a traditional manner. The transaction costs are high and the intermediate goods producing sector is not very transparent such that the intermediates can exploit some monopoly power. In the final output producing sector, the sub-markets are assumed to be monopolistic competitive with a constant mark-up margin on unit production costs.

In the first phase of the diffusion of the Internet, the early adopters in the final output market experience some efficiency gains by using the Internet. The transaction costs of the deliveries between intermediate producing firms and the final output-producing firms decrease. Both firms can appropriate a part of these efficiency gains and because other firms still face higher transaction costs, the efficiency gains lead to an increase of gross profits. But because there are just a few, or no, other firms who use the Internet, the efficiency gains in terms of lower marginal production costs are rather small. However, the presence of network effects is one of the main characteristics of networks like the Internet. If more firms invest in the Internet, more suppliers of intermediate goods will also do so and more applications will become available such that the marginal production costs will decrease if more firms use the Internet for their business-to-business commerce. This creates new incentives for other firms to invest in Internet technologies and the efficiency gains increase for all users. In the mean time, the relative number of firms is still small and the profits of these early adopters are relative high. This creates incentives for other firms to invest in Internet technologies too. Again, this causes an increase of the efficiency gains, but it also implies that more firms can produce against the same, low, marginal cost such that the markets become more competitive. The profits of the Internet using firms decrease but are still higher than the profits of the laggards. More important, due to the increased competition on the _low marginal cost market_, the mark-up margin on production cost decrease, which is exactly what we want to show. So we use the diffusion of the Internet as an explanation of the mark-up margin on marginal cost in the first phase and a decrease of the mark-up in the second phase of the diffusion process. This fits exactly in the econometric explanation given by Brayton et al. (1999).

Firms adopting the Internet for Business-to-Business electronic commerce and for electronic transfer of information report considerable gains in efficiency. This implies that firms who use the Internet to exchange information; to link their internal information systems with the systems of the suppliers of intermediate goods and services, and for other forms of business-to-business commerce can operate at lower (marginal) cost than firms who do not invest in Internet technologies. It is obvious that not all firms used the Internet for their (business-to-business) commerce from the outset and even if firms moved to the Internet, they did not all do it to the full extent immediately. Studies on adoption and diffusion of new technologies focus on such transition processes and try to explain why not all firms move immediate to a new (more profitable) technology.

The basic assumption is that firms differ from each other with respect to one or more characteristics that are important for investment decisions.12 For instance, some firms can be more risk averse than others, whereas the adoption of a new technology is experienced as an investment that bears some risks, or of which the expected profitability is not known.

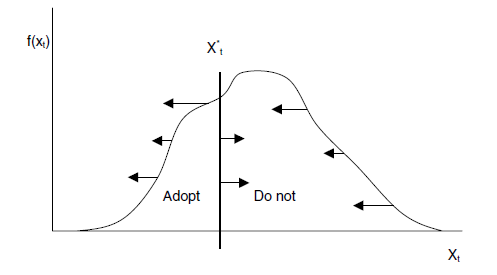

Fig.1. Adoption of a new technology.

Other reasons for not adopting technology can be the size of adjustment

cost. If investment in a new technology involves cost of adjustment that depends for instance on firm size, small firms, with low adjustment cost, may adopt a new, but costly, technology whereas larger firms, with relative higher adjustment cost, may rationally decide not to adopt. For example, the adjustment costs are plotted along the horizontal axis in Fig.1 and the number of corresponding firms along the vertical axis. Moving from the left to the right we find firms with increasing (expected) adjustment cost. The net profits – defined as the increased profits minus the investment cost, so excluding adjustment costs – function as a threshold.

Firms with expected adjustment cost below the net profits will invest in that technology and other firms not. A diffusion process can be explained if either the threshold moves to the right, e.g. due to decreased investment cost or increased profits, or the distribution moves to the left, e.g. due to decreasing adjustment costs. So a typical characteristic of these profit models is that either moving the threshold or the distribution, or both generate a diffusion curve. The forces behind these movements are either exogenous or endogenous.

In the case of increased wages, which is the case in the current low-inflation/high growth experience in the US, the increase in production cost is compensated by the decrease of the mark-up such that we indeed can explain the current low inflation experience. However, in the end when the diffusion process stops, the mark-up will return to its old value and inflation will start rising if the upward pressure from the labour market persists. So this model can explain low inflation, combined with high output growth and low unemployment, but only for the short term. The model predicts that in the long run inflation will return to its normal value. Note that the productivity explanation found in the literature – where changes in the growth rate of productivity are not incorporated instantaneously in the wage rate – works in the same direction and is also temporary in nature.

The labour market in new information economy

The ‘New Economy’, broadly defined by the extension of information and communication technologies (ICT or IT), particularly the Internet, to economic activity, is changing the labour market. The advent of ICT has shifted demand for labour toward workers with skills complementing the new technologies. The low cost of transmitting information over the Internet is shifting job search and recruitment activities to the Web. The ease of communicating and interacting over the Internet has led unions to experiment with web-based modes of servicing members and carrying their message to the wider public. The new technologies, together with other important changes, such as the continued increase in the educational attainment of the work-force, shift of employment to service sectors, and increased employment of women, is producing a labour market that differs greatly from the industrial labour market that characterized the twentieth century.

Two outstanding claims about the impact of computers and the Internet on work appear to be vast exaggerations, at least at this time. The first is the ‘death of distance’ claim that the Internet eliminates the importance of location to work activities, weakening the economic rationale for cities, in particular. The Progressive Policy Institute (PPI) has stated this claim sharply: ‘As an increasing share of economic inputs and outputs are in the form of electronic bits, the old locational factors diminish in importance’.

Perhaps the best example of the reduced importance of locality is teleworkin - the process of working at home at least one day a week while maintaining contact with one’s office through computer technology. In the USA an estimated 25m workers telework. In the EU an estimated 9.1m workers telework. But the possibility for interacting digitally rather than face to face has not produced a dispersal of new-economy jobs. To the contrary, traditional agglomeration economies operate in ICT sectors as much or more than elsewhere, producing geographic clusters of ICT, of which Silicon Valley and Boston’s Route 128 are the most prominent examples. One presumed reason for this is that much important information, be it business, or scientific, or technological, is tacit, requiring human interaction to be effectively transmitted. This does not mean that the Internet has no effects on the location of business activities or employment. Quah (2000 a) has suggested that the ‘weightless economy’ could produce more subtle changes in the coordination and timing of business activity than the death of distance—waves of business activity across different time zones. Consider the efficiency advantage of dividing a work project so that people in one time zone begin the project, then pass the product to people in another zone, who do the same. If people work on an 8-hour day, this would link workers in time zones differing by just 8 hours, creating a 24-hour three-shift work day for the product. The development of Bangalore as a programming work site linked largely to the USA could be due to this time zone effect.

The second claim about new-economy jobs is that they produce employee/employer relations that diverge greatly from the traditional long-term permanent jobs that have characterized capitalist economies. In the mid-1990s Fortune heralded ‘the end of the job’ and various commentators have since argued that new-economy jobs are disproportionately short-term contract work, rather than full-time employment. The idea is that in the new economy, people work on projects rather than for employers. This is the pattern of production in Hollywood, where a producer puts together a team to make a movie, then dissolves the team when the production is over, so that movie personnel move from temporary contract to temporary contract.

Some new-economy ICT work follows this pattern. There is an active market in ‘e-work’, where market intermediaries bring together ICT or other specialists with firms for contract work, providing a market venue in which to conduct the operation and reputation capital to assure that neither the worker nor firm is ripped off. One large operation is www.eworks.com , which as of summer 2002 had listed some $14.6 billion of contracting work for some 332,736 users, who made 102,791 transactions. In another part of its Internet business, it managed the full transactions for contract workers, processing time sheets, paychecks, vendor invoices, and consolidated client invoices. In this type of market, firms and workers usually report afterwards on the success of the match so that they develop reputations for future work arrangements.

With many workers and firms using the Internet for job search and recruitment, it is not surprising that the distribution of skills and jobs goes far beyond ICT occupations or industries, where Internet recruitment began. ICT and new-economy sectors or areas of the economy do make more extensive use of the Web as a venue for matching workers and firms than other areas. In the UK, job search on the Web is more common in the south-east than in the older industrial north.

The reason for the rapid movement of job search and recruitment to the Web is simple: workers seeking jobs want information about the jobs on offer, while employers seeking workers want information about persons seeking work, and the Internet is the lowest-cost way to transmit information throughout the economy. Firms can post advertisements for jobs on the Web for roughly a tenth the price of buying a want-ad in newspaper classifieds and obtain rapid responses through online applications. Workers can search for a wide variety of jobs and apply relatively easily for those jobs without leaving their home (or perhaps their office) and can be notified by e-mail that particular firms are interested in them. They also can obtain diverse information about prospective employers from the web.

Internet job search and recruitment offer three potential efficiency gains to the economy: reduced transactions costs; speedier clearing of the job market; and better matching between workers and vacancies.

Internet recruitment has the potential for making its biggest contribution to the labour market by producing better job matches. By diffusing information about jobs widely, the Internet should help break down ‘old boys networks’ and traditional geographic barriers. Someone sitting in an Internet cafe in a small village in Portugal, for example, can peruse jobs in London or Paris and apply. If they have the skills, they will be able to beat out a less qualified candidate from the local area. Here too, however, the critical bottleneck appears to be the back-end technology for matching worker qualifications with job requirements. Better matching could, however, have one potentially adverse effect on the job market.

Thus internet and ICT technologies were changing the labour market and labour organizations inequality by making clearer which workers are best suited for given jobs and raising competition for their services. There is, as yet, no empirical analysis on this issue.

Conclusion

The concept of the ‘New Information Economy’ was coined in the business press in the mid-1990s to mean an economy which is able to benefit from the two trends shaping the world economy today - the globalization of business and the revolution in information and communication technology (ICT). The first trend can be defined simply as the triumph of capitalism after the collapse of socialism. Markets are being liberalized, and trade and capital flows are being deregulated all over the world. It is evident that international trade and investment now play a greater role in most countries’ economic policies than 15–20 years ago. The driving forces of the second trend are the rapid improvement in the quality of ICT equipment and software and the sharp decline in their prices, the convergence in communication and computing technologies, and the fast growth in network computing via the Internet.

The prevailing view in economics is that economic growth is, indeed, driven by advances in technology - that is, ideas about how to produce more efficiently. Given that ICT is generally regarded as the current manifestation of the ongoing sequence of technological revolutions, it can be seen as the key factor driving economic growth in present-day societies.

References

Richard B. Freeman – «The labour market in the new information economy», Oxford review of economic policy, vol. 18, no. 3, 2002

Matti Pohjola – «The new economy in growth and development», Oxford review of economic policy, vol. 18, no. 3, 2002

Andrew Graham – «The assessment: economics of the internet», Oxford review of economic policy, vol. 17, no. 2, 2001

George Liagouras – «The political economy of post-industrial capitalism», SAGE Publication, Thesis Eleven, Number 81, May 2005: 20-35, www.sagepub.com

J. Bradford De Long – «The Next Economy?», Internet Publishing and Beyond: The Economics of Digital Information and Intellectual Property (Cambridge: MIT Press), 1997, www.osaka.law.miami.edu/~froomkin/articles/newecon.htm

Matti Pohjola – «The New Economy: facts, impacts and policies», Information Economics and Policy 14, 2002, 133-144

Sandra Braman – «The Micro- and Macroeconomics of Information», Annual Review of Information Science and Technology

Roberto Verzola – «Information Economy», January 2006, www.vecam.org/article724.html

Huub Meijers – «Diffusion of the Internet and low inflation in the information economy», Information Economics and Policy 18, 2006, 11-23

Adam Arvidsson – «The World of Information», Springer , Journal of Technology Transfer 31, 2006, 17–30