- •I. Read and translate the text. Sociology

- •II. Answer the following questions:

- •VIII. Answer: What are the sociologists concerned with? Use the words in brackets.

- •IX. Translate the following sentences into Russian:

- •Unit II

- •I. Read and translate the text: Social Barometer

- •II. Answer the following questions:

- •Word study

- •IV. Complete the following sentences:

- •Unit III

- •I. Read and translate the text: The Origins of Sociology

- •II. Answer the following questions:

- •III. Complete the following sentences:

- •IV. Divide the text into logical parts and make up an outline of the text.

- •V. Speak on:

- •VI. Read the text and entitle it:

- •Word study

- •Unit IV

- •I. Read and translate the text: Sociological Theory

- •II. Answer the following questions:

- •III. Agree or disagree with the following:

- •IV. Divide the text into logical parts and make up a plan of the text.

- •VI. Contradict the following statements:

- •VII. Translate the text in writing: Social Change and the Development of Sociology

- •Word study

- •I. Find in the text «Sociological Theory» English equivalents for:

- •II. Find in the text antonyms for:

- •III. Fill in the blanks with the words given below in the brackets:

- •IV. Read and translate the following sentences taking into account different meanings of the word 'experience':

- •V. Role-play.

- •I. Read the text and answer the following questions:

- •Theoretical Paradigms

- •II. Be ready to speak on:

- •III. You have just heard three reports. What paper do you think to be the best one? Give your arguments. Use the following:

- •IV. Read and translate the text: The Methods of Sociological Research

- •Experiments.

- •Survey Research

- •Questionnaires and Interviews

- •V. Enumerate all methods of sociological research. What method do you consider to be the most productive? Give your reasons.

- •VI. Answer the following questions:

- •Word study

- •III. Translate the following sentences into Russian with:

- •V. Develop the following situations:

- •Unit VI

- •I. Read and translate the text: The Structure of Social Interaction

- •Social Structure and Individuality

- •II. Answer the following questions:

- •Summary

- •Word study

- •I. Find in the text “The Structure of Social Interactions” English equivalents for:

- •II. Arrange the following words into pairs of antonyms:

- •III. Make up sentences choosing an appropriate variant from 1) – 7):

- •IV. Make up dialogues according to the following situations:

- •Unit VII

- •I. Look through the text and find the definitions of:

- •II. Read and translate the text. Role

- •Figure 1. Status Set and Role Set

- •Strain and Conflict

- •Dramaturgical Analysis: “The Presentation of Self”

- •IX. Answer the questions:

- •Word study

- •I. Find in the texts English equivalents for:

- •III. Read and translate the following sentences:

- •IV. Make up questions and ask your friend on:

- •V. Complete the following sentences:

- •Unit VIII

- •Kinds of Groups

- •IV. Find the facts to prove that:

- •V. Divide the text into three logical parts.

- •VII. Discuss in the group the following problems:

- •The Nature of Group Cohesiveness

- •XIV. Read and translate the text. Primary and Secondary Groups

- •XV. Answer the following questions.

- •XVI. Contradict the following statements. Start your sentence with: “Quite on the contrary...”

- •XVII. Ask your friend:

- •Divide the text into logical parts and give a heading to each part.

- •Find a leading sentence in each paragraph of the text.

- •Primary Groups and Secondary Groups

- •Give examples of primary and secondary groups.

- •Characterize in brief:

- •XXIV. Read the text and say what new information is contained in it. Networks

- •Word study

- •I. Find in the text “Primary and Secondary Groups” English equivalents for:

- •II. Make up word-combinations and translate them into Russian.

- •IV. Make up your own sentences with — “to be of importance, to be of value” - and ask your partner to translate them.

- •Unit IX

- •I. Read and translate the text. Group Dynamics

- •Group Leadership

- •The Importance of Group Size

- •Figure 3. Group Size and Relationships

- •VII. Read the text again and note the difference between in-groups and out-groups.

- •VIII. Prepare a report on “Group Dynamics and Society.” unit X

- •I. Read and translate the text.

- •Deviance

- •Biological Explanations of Deviance

- •VII. Speak on:

- •VIII. Translate the text in writing. Deviance is a Product of Society?

The Importance of Group Size

Being the first person to arrive at a party affords the opportunity to observe a fascinating process in group dynamics. When fewer than about six people interact in one setting, a single conversation is usually maintained by everyone. But with the addition of more people, the discussion typically divides into two or more conversations. This example is a simple way of showing that size has important effects on the operation of social groups.

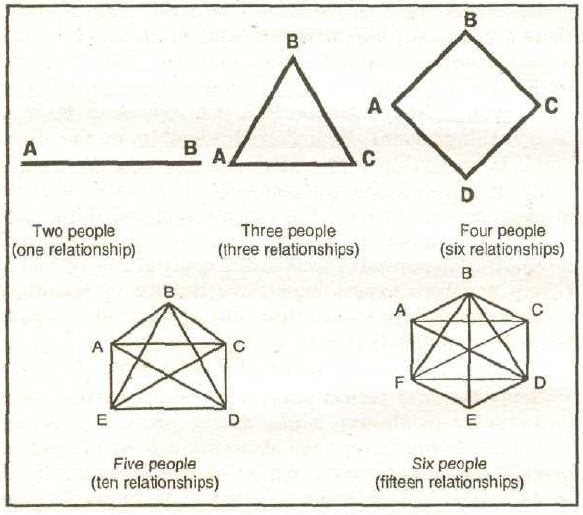

The basis for this dynamic lies in the mathematical connection between the number of people in a social group and the number of relationships among them as shown in Figure 3. Two people are joined in a single relationship; adding a third person results in three relationships, a fourth person yields six. As additional people are added one at a time - according to what mathematicians call an arithmetic increase the number of relationships increases very rapidly - in what is called a geometric increase. By the time six people have joined one conversation, there are fifteen different relationships among them, which explains why the conversation usually divides by this point.

Figure 3. Group Size and Relationships

Social groups with more than three members tend to be more stable because the lack of interest on the part of one or even several members does not directly threaten the group’s existence. Furthermore, larger social groups tend to develop more formal social structure - with a variety of statuses and roles - which stabilize their operation. However, larger social groups inevitably lack the increase of personal relationships that are possible in the smallest groups.

Is there an ideal size for a social group? The answer, of course, depends on the group`s purpose.

II. Find in the text the definitions of:

group dynamics;

instrumental leadership;

expressive leadership;

an arithmetic increase;

a geometric increase.

III. Answer the following questions.

How do social groups vary?

What are the ways by which a person may be recognized as a leader?

Is there a category of people who might be considered as ‘natural leaders’?

What is the difference between instrumental and expressive leaders?

What do large social groups tend to develop?

What group do you think is regarded to be an ideal one?

Characterize in brief.

The core of group dynamics.

An ideal social group.

The importance of group size.

The group polarization phenomenon.

V. Choose the qualities you think to be necessary for an ideal leader:

emotional, aggressive, active, brave, clever, strong, intuitive, tall, handsome, good with money, mechanically-minded, tender.

You may expand the list. But give reasons of your choice.

VI. Read the text and state its general idea.

In-groups and Out-groups

By the time children are in the early grades of school, much of their activity takes place within social groups. They eagerly join some groups, but avoid - or are excluded from - others. Based on sex as a master status, for example, girls and boys often form distinct play groups with patterns of behaviour culturally defined as feminine and masculine.

On the basis of sex, employment, family ties, personal tastes, or some other category, people often identify others positively with one social group while opposing other groups. Across the United States, for example, many high school students wear jackets with the name of their school on the back and place school decals on their car windows to symbolize their membership in the school as a social group. Students who attend another school may be the subject of derision simply because they are members of a competing group.

This illustrates the general process of forming in-groups and out-groups. An in-group is a social group with which people identify and toward which they feel a sense of loyalty. An in-group exists in relation to an out-group, which is a social group with which people do not identify and toward which they feel a sense of competition or opposition. Defining social groups this way is commonplace. A sports team is an in-group to its members and an out-group to members of other teams. The Democrats in a certain community may see themselves as an in-group in relation to Republicans. In a broader sense, Americans share some sense of being an in-group in relation to Russian citizens or other nationalities. All in-groups and out-groups are created by the process of believing that “we” have valued characteristics that “they” do not.

This process serves to sharpen the boundaries among social groups, giving people a clearer sense of their location in a world of many social groups. It also heightens awareness of the distinctive characteristics of various social groups, though not always in an accurate way. Research has shown, however, that the members of in-groups hold unrealistically positive views of themselves and unfairly negative views of various out-groups. Ethnocentrism, for example, is the result of overvaluing one's own way of life, while simultaneously devaluing other cultures as out-groups.