- •Overview

- •Preface

- •Translator’s Note

- •Contents

- •1. Fundamentals

- •Microscopic Anatomy of the Nervous System

- •Elements of Neurophysiology

- •Elements of Neurogenetics

- •General Genetics

- •Neurogenetics

- •Genetic Counseling

- •2. The Clinical Interview in Neurology

- •General Principles of History Taking

- •Special Aspects of History Taking

- •3. The Neurological Examination

- •Basic Principles of the Neurological Examination

- •Stance and Gait

- •Examination of the Head and Cranial Nerves

- •Head and Cervical Spine

- •Cranial Nerves

- •Examination of the Upper Limbs

- •Motor Function and Coordination

- •Muscle Tone and Strength

- •Reflexes

- •Sensation

- •Examination of the Trunk

- •Examination of the Lower Limbs

- •Coordination and Strength

- •Reflexes

- •Sensation

- •Examination of the Autonomic Nervous System

- •Neurologically Relevant Aspects of the General Physical Examination

- •Neuropsychological and Psychiatric Examination

- •Psychopathological Findings

- •Neuropsychological Examination

- •Special Considerations in the Neurological Examination of Infants and Young Children

- •Reflexes

- •4. Ancillary Tests in Neurology

- •Fundamentals

- •Imaging Studies

- •Conventional Skeletal Radiographs

- •Computed Tomography (CT)

- •Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- •Angiography with Radiological Contrast Media

- •Myelography and Radiculography

- •Electrophysiological Studies

- •Fundamentals

- •Electroencephalography (EEG)

- •Evoked potentials

- •Electromyography

- •Electroneurography

- •Other Electrophysiological Studies

- •Ultrasonography

- •Other Ancillary Studies

- •Cerebrospinal Fluid Studies

- •Tissue Biopsies

- •Perimetry

- •5. Topical Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis of Neurological Syndromes

- •Fundamentals

- •Muscle Weakness and Other Motor Disturbances

- •Sensory Disturbances

- •Anatomical Substrate of Sensation

- •Disturbances of Consciousness

- •Dysfunction of Specific Areas of the Brain

- •Thalamic Syndromes

- •Brainstem Syndromes

- •Cerebellar Syndromes

- •6. Diseases of the Brain and Meninges

- •Congenital and Perinatally Acquired Diseases of the Brain

- •Fundamentals

- •Special Clinical Forms

- •Traumatic Brain injury

- •Fundamentals

- •Traumatic Hematomas

- •Complications of Traumatic Brain Injury

- •Intracranial Pressure and Brain Tumors

- •Intracranial Pressure

- •Brain Tumors

- •Cerebral Ischemia

- •Nontraumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage

- •Infectious Diseases of the Brain and Meninges

- •Infections Mainly Involving the Meninges

- •Infections Mainly Involving the Brain

- •Intracranial Abscesses

- •Congenital Metabolic Disorders

- •Acquired Metabolic Disorders

- •Diseases of the Basal Ganglia

- •Fundamentals

- •Diseases Causing Hyperkinesia

- •Other Types of Involuntary Movement

- •Cerebellar Diseases

- •Dementing Diseases

- •The Dementia Syndrome

- •Vascular Dementia

- •7. Diseases of the Spinal Cord

- •Anatomical Fundamentals

- •The Main Spinal Cord Syndromes and Their Anatomical Localization

- •Spinal Cord Trauma

- •Spinal Cord Compression

- •Spinal Cord Tumors

- •Myelopathy Due to Cervical Spondylosis

- •Circulatory Disorders of the Spinal Cord

- •Blood Supply of the Spinal Cord

- •Arterial Hypoperfusion

- •Impaired Venous Drainage

- •Infectious and Inflammatory Diseases of the Spinal Cord

- •Syringomyelia and Syringobulbia

- •Diseases Mainly Affecting the Long Tracts of the Spinal Cord

- •Diseases of the Anterior Horns

- •8. Multiple Sclerosis and Other Myelinopathies

- •Fundamentals

- •Myelin

- •Multiple Sclerosis

- •Other Demyelinating Diseases of Unknown Pathogenesis

- •9. Epilepsy and Its Differential Diagnosis

- •Types of Epilepsy

- •Classification of the Epilepsies

- •Generalized Seizures

- •Partial (Focal) Seizures

- •Status Epilepticus

- •Episodic Neurological Disturbances of Nonepileptic Origin

- •Episodic Disturbances with Transient Loss of Consciousness and Falling

- •Episodic Loss of Consciousness without Falling

- •Episodic Movement Disorders without Loss of Consciousness

- •10. Polyradiculopathy and Polyneuropathy

- •Fundamentals

- •Polyradiculitis

- •Cranial Polyradiculitis

- •Polyradiculitis of the Cauda Equina

- •Polyneuropathy

- •Fundamentals

- •11. Diseases of the Cranial Nerves

- •Fundamentals

- •Disturbances of Smell (Olfactory Nerve)

- •Neurological Disturbances of Vision (Optic Nerve)

- •Visual Field Defects

- •Impairment of Visual Acuity

- •Pathological Findings of the Optic Disc

- •Disturbances of Ocular and Pupillary Motility

- •Fundamentals of Eye Movements

- •Oculomotor Disturbances

- •Supranuclear Oculomotor Disturbances

- •Lesions of the Nerves to the Eye Muscles and Their Brainstem Nuclei

- •Ptosis

- •Pupillary Disturbances

- •Lesions of the Trigeminal Nerve

- •Lesions of the Facial Nerve

- •Disturbances of Hearing and Balance; Vertigo

- •Neurological Disturbances of Hearing

- •Disequilibrium and Vertigo

- •The Lower Cranial Nerves

- •Accessory Nerve Palsy

- •Hypoglossal Nerve Palsy

- •Multiple Cranial Nerve Deficits

- •12. Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves

- •Fundamentals

- •Spinal Radicular Syndromes

- •Peripheral Nerve Lesions

- •Fundamentals

- •Diseases of the Brachial Plexus

- •Diseases of the Nerves of the Trunk

- •13. Painful Syndromes

- •Fundamentals

- •Painful Syndromes of the Head And Neck

- •IHS Classification of Headache

- •Approach to the Patient with Headache

- •Migraine

- •Cluster Headache

- •Tension-type Headache

- •Rare Varieties of Primary headache

- •Symptomatic Headache

- •Painful Syndromes of the Face

- •Dangerous Types of Headache

- •“Genuine” Neuralgias in the Face

- •Painful Shoulder−Arm Syndromes (SAS)

- •Neurogenic Arm Pain

- •Vasogenic Arm Pain

- •“Arm Pain of Overuse”

- •Other Types of Arm Pain

- •Pain in the Trunk and Back

- •Thoracic and Abdominal Wall Pain

- •Back Pain

- •Groin Pain

- •Leg Pain

- •Pseudoradicular Pain

- •14. Diseases of Muscle (Myopathies)

- •Structure and Function of Muscle

- •General Symptomatology, Evaluation, and Classification of Muscle Diseases

- •Muscular Dystrophies

- •Autosomal Muscular Dystrophies

- •Myotonic Syndromes and Periodic Paralysis Syndromes

- •Rarer Types of Muscular Dystrophy

- •Diseases Mainly Causing Myotonia

- •Metabolic Myopathies

- •Acute Rhabdomyolysis

- •Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathies

- •Myositis

- •Other Diseases Affecting Muscle

- •Myopathies Due to Systemic Disease

- •Congenital Myopathies

- •Disturbances of Neuromuscular Transmission−Myasthenic Syndromes

- •15. Diseases of the Autonomic Nervous System

- •Anatomy

- •Normal and Pathological Function of the Autonomic Nervous System

- •Sweating

- •Bladder, Bowel, and Sexual Function

- •Generalized Autonomic Dysfunction

- •Index

180

11 Diseases of the Cranial Nerves

Fundamentals . . . |

180 |

|

Lesions of the Trigeminal Nerve . . . |

195 |

|

|

Disturbances of Smell (Olfactory Nerve) . . . |

180 |

Lesions of the Facial Nerve . . |

. 196 |

|

|

|

Neurological Disturbances of Vision |

|

Disturbances of Hearing and Balance; Vertigo . . . |

199 |

|||

(Optic Nerve) . |

. . 180 |

|

The Lower Cranial Nerves . . . |

204 |

|

|

Disturbances of Ocular and Pupillary Motility . . . |

183 Multiple Cranial Nerve Deficits . . . |

206 |

|

|||

Fundamentals

The cranial nerves can be affected by disease in isolation, or as a component of a wider disease process. Cranial nerve deficits are caused by lesions of their nuclei or tracts in the brainstem, or of the peripheral course of the nerves themselves and their branches.

The anatomical relationships of the cranial nerves to the base of the skull are shown in Fig. 3.3 (p. 17), while their anatomical course and distribution are summarized in Table 3.3 (p. 17). The causes and clinical manifestations of cranial nerve lesions are discussed in detail in this chapter.

Disturbances of Smell (Olfactory Nerve)

Anatomy. The peripheral olfactory receptors can only be excited by substances dissolved in fluid. The receptors of the olfactory mucosa project their axons through the cribriform plate to the olfactory bulb (Fig. 3.3, p. 17), which lies on the floor of the anterior cranial fossa, beneath the frontal lobe. After a synapse onto the second neuron of the pathway in the olfactory bulb, olfactory fibers travel onward through the lateral olfactory striae to the amygdala and other areas of the temporal lobe. Olfactory fibers also travel by way of the medial olfactory striae to the subcallosal area and the limbic system.

Clinical manifestations. Techniques for examining the sense of smell are discussed on p. 16. Only the following types of olfactory disturbances are relevant to neurological diagnosis:

Anosmia. A more or less complete loss of the sense of smell is usually due to disorders of the nose, most commonly rhinitis sicca. The most common neurological

cause of anosmia is traumatic brain injury resulting in a brain contusion and/or traumatic avulsion of the olfactory fibers as they traverse the cribriform plate. The anosmia regresses in one-third of patients, but distortions of olfactory perception, so-called parosmias, often persist, sometimes in the form of unpleasant kakosmia (see below). Anosmia is the characteristic symptom of an olfactory groove meningioma and is often its initial manifestation. Rarer causes of hyposmia include Paget disease, Parkinson disease, prior laryngectomy, and diabetes mellitus. Medications often alter or impair the sense of smell. Anosmia always carries with it an impairment of the sense of taste (ageusia). The differential perception of gustatory stimuli requires not only an intact sense of taste, but also an intact sense of smell.

Olfactory hallucinations—usually in the form of spontaneous kakosmia—are produced by epileptic discharges from a focus in the anterior, medial portion of the temporal lobe. These hallucinations are sometimes called uncinate fits.

Neurological Disturbances of Vision (Optic Nerve)

Visual disturbances can be caused by lesions of the retina or of its connections with the visual cortex. Depending on the etiology, the disturbance may consist of an impairment of visual acuity (ranging to total blindness) or a visual field defect, and these

problems may appear either suddenly or gradually. In addition, the site of the lesion determines the type of visual field defect that will be present and whether it will affect only one eye or both. A simple clinical rule is that lesions of the retina and

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Neurological Disturbances of Vision (Optic Nerve)

optic nerve impair visual acuity, while lesions of the optic chiasm and distal components of the visual pathway (from the optic tract to the visualcortex) produce visual field defects, usually sparing visual acuity. Retrochiasmatic lesions impair visual acuity only when they are bilateral.

Visual Field Defects

A visual field defect is defined as the absence of some part of the normal visual field. The manual confrontation technique for examining the visual field is shown on p. 19 and the use of special instrumentation for this purpose is presented on p. 65.

The diagnostic assessment of a visual field defect involves, first, localization of the underlying lesion to a particular part of the visual pathway on the basis of the characteristics described above; and, second, determination of the etiology on the basis of the clinical history, other findings of the neurological examination, and the results of ancillary tests.

Types of visual field defect and their localization.

Visual field defects may be either monocular or binocular. Monocular visual field defects are caused by unilateral retinal lesions or by partial lesions of the optic n., while binocular ones are caused by unilateral lesions of the visual pathway from the optic chiasm onward (cf. Fig. 3.6, p. 19).

The following types of visual field defect are characterized by their spatial configuration:

Hemianopsia: the defect occupies one half of the visual field (right or left).

Quadrantanopsia: the defect occupies one quarter of the visual field.

Scotoma: the defect occupies a small spot or patch within the visual field. So-called central scotoma is due to a lesion affecting the macula lutea or its efferent nerve fibers, resulting in an impairment of central vision and thus a reduction of visual acuity.

Temporal crescent: this is a preserved area of vision in the far lateral visual field on the side of a nearhemianopic visual field defect. The cause is a lesion of the contralateral occipital lobe sparing the rostral portion of the visual cortex on either side of the calcarine fissure.

Homonymous and heteronymous visual field defects. If a binocular visual field defect involves a corresponding area of the visual field in both eyes (e. g., the right half of the visual field in both eyes), it is called a homonymous visual field defect. For example, a lesion of the right optic tract, lateral geniculate body, optic radiation, or visual cortex produces a left homonymous hemianopsia, while a lesion of any of these structures on the left produces a right homonymous hemianopsia (cf. Fig. 3.6, p. 19). A lesion along the course of the optic radiation or in the visual cortex may affect only part of the radiating fibers or cortex, causing a homonymous defect that is less than a complete hemianopsia: thus, depending on the site and extent of the lesion, there may

be a homonymous quadrantanopsia or homonymous scotoma.

In contrast, a lesion of the optic chiasm produces a heteronymous visual field defect: most such lesions affect the decussating fibers derived from the nasal half of each retina, thereby causing a bitemporal hemianopsia or bitemporal quadrantanopsia. The visual field defect lies in the temporal half of each visual field, i. e., in the right half of the visual field of the right eye and the left half of the visual field of the left eye.

If a tumor, such as a pituitary adenoma, compresses the optic chiasm from below, there is initially an upper bitemporal quadrantanopsia, which is only later followed by bitemporal hemianopsia. If a tumor compresses the optic chiasm from above (e. g., a craniopharyngioma), there is initially a lower bitemporal quadrantanopsia, and later bitemporal hemianopsia.

If a tumor compresses the optic chiasm from one side, it will affect not only the decussating medial fibers, but also the uncrossed fibers from the retina on that side. The resulting visual field defect involves the entire visual field on the side of the lesion in addition to temporal hemianopsia on the opposite side.

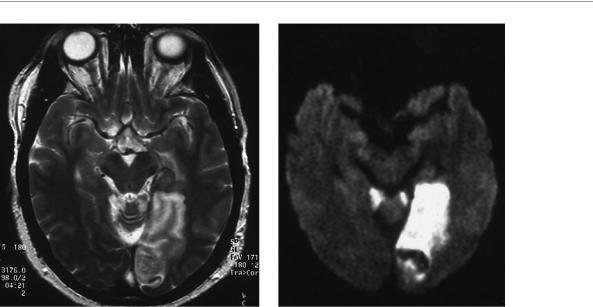

Etiologic classification of visual field defects. A visual field defect that arises suddenly is generally due to either ischemia or trauma. The “gestalt” of the visual field defect, too, can provide a clue to its etiology: thus, a temporal crescent is highly characteristic of a vascular lesion. A slowly progressive visual field defect suggests the presence of a brain tumor. In such patients, the patient may fail to notice the visual field defect, particularly if the tumor lies in the right parietal lobe. There may be visual hemineglect accompanying, or instead of, a “true” visual field defect. The patient ignores visual stimuli in the affected hemifield, even though he or she may still be able to see them; and, if the patient truly cannot see stimuli in that hemifield, he or she is nonetheless unaware of the defect. Neuroimaging studies generally reveal the site and nature of the underlying lesion (Fig. 11.1).

Special types of visual field defect. In the Riddoch phenomenon, the patient cannot see stationary objects in the affected area of the visual field, though movement can be perceived. In palinopsia, the perception outlasts the stimulus: the patient continues to “see” the presented image long after it has been removed. This phenomenon is produced by right temporo-occip- ital lesions.

Thieme Argo OneArgo bold

ArgoOneBold

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

181

Diseases of the Cranial Nerves

11

182 11 Diseases of the Cranial Nerves

a |

b |

Fig. 11.1 Infarct in the territory of the left posterior cerebral a. in a patient with right homonymous hemianopsia. MR image. a The axial T2-weighted image reveals abnormally bright signal in the cerebral cortex and in the underlying white matter, as well as a

Impairment of Visual Acuity

Sudden unilateral loss of vision, as long as its cause does not lie in the eye itself, is usually due to a lesion of the optic nerve. The sudden onset of the defect implies that it has been caused by ischemia. A defect of this type may be permanent, e. g., in occlusion of the central retinal a. due to temporal arteritis or embolization from an atheromatous plaque in the carotid a., or it may be temporary, in which case it is called amaurosis fugax (transient monocular blindness). Rarely, transient visual loss can be produced by a disturbance of neural function, such as migraine (retinal migraine). Papilledema, too, can be accompanied by episodes of sudden visual loss (amblyopic attacks). Ocular causes should not be forgotten in the differential diagnosis, e. g., retinal detachment, preretinal hemorrhage, or central vein thrombosis. Correct diagnosis requires a precise clinical history and meticulous examination of the optic disc and fundus.

Sudden bilateral loss of vision may be due to bilateral retinal ischemia, e. g., on standing up in a patient with aortic arch syndrome. Certain types of intoxication can also rapidly produce bilateral optic nerve lesions, e. g., methanol poisoning, which causes blindness within hours. Yet, bilateral visual loss of more or less sudden onset is much more commonly due to simultaneous ischemia of both occipital lobes. Such events are often preceded by hemianopic episodes and loss of color vision as prodromal manifestations. The possible causes include embolization into the territory of the posterior cerebral aa. on both sides simultaneously and compressive occlusion of the posterior cerebral aa. by an intracranial mass. Patients often deny that they cannot see (anosognosia). Despite the severe visual loss, the

small hemorrhage within the infarct. b The diffusion-weighted MRI reveals diminished diffusion of protons and water molecules in the first few days after the event. Fresh infarcts are very well seen in this type of study. The hemorrhage, too, is visible in this case.

pupillary light reflex is still present, because the pathway for visual impulses to the lateral geniculate body, where the fibers for the reflex branch off, remains intact. The visual evoked potentials (VEP, p. 56 and Fig. 4.19, p. 59), however, are pathological.

Progressive impairment of visual acuity in one or both eyes. Unilateral impairment is due to a process causing more or less rapid, progressive damage to the optic nerve or chiasm. Retrobulbar neuritis (inflammation of the optic n. between the retina and the chiasm) and optic papillitis (inflammation of the optic n. at the level of the optic disc) cause unilateral visual loss within two days or a little longer. Progressive, unilateral visual loss should also always prompt suspicion of a mass: optic glioma, for example, is a primary tumor within the optic n. that is more common in children and an optic sheath meningioma can compress the nerve from outside. Retrobulbar neuritis rarely occurs bilaterally, sometimes in combination with myelitis. Further causes of bilateral loss of visual acuity are Leber hereditary optic atrophy and tobaccoalcohol amblyopia. In the latter condition, the most prominent initial finding is an inability to distinguish the colors red and green. Vitamin B12 deficiency can cause progressive optic atrophy in combination with polyneuropathy.

Pathological Findings of the Optic Disc

This is an area requiring close collaboration between the neurologist and the ophthalmologist.

Papilledema is usually a reflection of intracranial hypertension, but it can also be seen in infectious and inflam-

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.