- •Contents

- •Figures

- •Preface and acknowledgements

- •1 Formulating questions – the ‘music and society’ nexus

- •Getting into the music

- •Music as a medium of social relation

- •Conceptualizing music as a force

- •Relations of music production, distribution and use

- •The interactionist critique of semiotics – overview

- •Mapping gender on to music and music on to gender – the case of Carmen

- •Artefacts and users

- •Verbal meaning in naturally occurring speech situations

- •3 Music as a technology of self

- •Knowing what you need – self-programming and musical material

- •Getting into focus – music and mental concentration

- •Relevant units of affect

- •Music and self-identity

- •Musical memories and the choreography of feeling

- •Finding ‘the me in music’ – musically composed identities

- •4 Music and the body

- •The sociology of the body

- •Getting into the rhythm of life

- •Musical entrainment

- •Paradox of cure in the neonatal unit – the body’s sonic resources

- •How does music work? Key questions

- •Embodied awareness and embodied security

- •Music and bodily security

- •More questions

- •A naturally occurring experiment

- •‘Let the music move you up and down’ – the warm-up

- •Packaging and repackaging music; packaging and repackaging bodies

- •Gearing up and staying up – musical devices

- •Music as a prosthetic technology of the body

- •Music prosthetic technology and daily life

- •5 Music as a device of social ordering

- •Musical prescription? Music and intimate culture

- •Music and collective occasions

- •Music as a touchstone of social relations

- •Music for strangers

- •Music in public places – the case of the retail sector

- •The sound of consumption

- •Case study: music on an English high street

- •How and where are store music policies made?

- •Creating scene, creating agency – music as ambience

- •What does music do within organizational settings?

- •The sounds of silence

- •6 Music’s social powers

- •Non-rational orderings

- •Reprise – what does music do?

- •Musical power and its mechanisms

- •Politics of music in the public space

- •Bibliography

- •Index

6Music’s social powers

Music has organizational properties. It may serve as a resource in daily life, and it may be understood to have social ‘powers’ in relation to human social being. The previous chapters have moved from music’s connection to what are generally thought of as the innermost recesses of the self – emotion, memory, self-identity – through music’s interrelationship with the body, to music’s role as an active ingredient within the settings of interaction. Music is but one type of cultural material; volumes could also be written about the role of many other types of aesthetic materials – visual, even olfactory – in relation to human agency. And music’s ‘powers’ vacillate; within some contexts and for some people, music is a neutral medium.

At other times, music’s powers may be profound. In a footnote to his famous study of encephalitis lethargica survivors, Oliver Sacks speaks of music’s liberating ‘power’ in relation to Parkinsonism su erers:

This was shown beautifully, and discussed with great insight, by Edith T., a former music teacher. She said that she had become ‘graceless’ with the onset of Parkinsonism, that her movements had become ‘wooden, mechanical – like a robot or doll’, that she had lost her former ‘naturalness’ and ‘musicalness’ of movement, that – in a word – she had been ‘unmusicked’. Fortunately, she added, the disease was ‘accompanied’ by its own cure. I raised an eyebrow: ‘Music,’ she said, ‘as I am unmusicked, I must be remusicked.’ Often she said, she would find herself ‘frozen’, utterly motionless, deprived of the power, the impulse, the thought, of any motion; she felt at such times ‘like a still photo, a frozen frame’ – a mere optical flat, without substance or life. In this state, this statelessness, this timeless irreality, she would remain, motionless-helpless, until music came: ‘Songs, tunes I know from years ago, catchy tunes, rhythmic tunes, the sort I loved to dance to.’ (1990:60n, emphasis in original)

Upon hearing or imagining music, Edith T. explained to Sacks, her ‘inner music’ – the capacity to move and to act – was returned. ‘It was like’, she said, ‘suddenly remembering myself, my own living tune’ (1990:60n).

Sacks refers to Kant’s conception of music as ‘the quickening art’, a means for arousing a person’s liveliness. For Edith T., as Sacks puts it, music aroused, ‘her living-and-moving identity and will, which is otherwise

151

152 Music’s social powers

dormant for so much of the time’ (1990:61n). He goes on to say, ‘this is what I mean when I speak of these patients as “asleep,” and why I speak of their arousals as physiological and existential “awakenings,” whether these be through the spirit of music or living people, or through chemical rectification of deficiencies in the “go” parts of the brain’ (1990:61n).

This link between music and ‘awakening’ is not metaphorical, it is fiduciary, in the sense that music provides a basis of reckoning, an animating force or flow of energy, feeling, desire and aesthetic sensibility that is action’s matrix. The study of music and its powers within social life thus opens a window on to agency as a human creation, to its ‘here and now’ as existential being. This vista abounds with life; it has vibrancy, a busy or tapestried quality.

In his introduction to his phenomenology of everyday experience, Alberto Melucci eloquently defends the importance of this realm:

Each and every day we make ritual gestures, we move to the rhythm of external and personal cadences, we cultivate our memories, we plan for the future. And everyone else does likewise. Daily experiences are only fragments in the life of an individual, far removed from the collective events more visible to us, and distant from the great changes sweeping through our culture. Yet almost everything that is important for social life unfolds within this minute web of times, spaces, gestures, and relations. It is through this web that our sense of what we are doing is created, and in it lie dormant those energies that unleash sensational events. (1996b:1)

The playing out of social change, politics, social movements, relations of production is experienced and renewed from within this ‘web’, as Melucci calls it; it is from within the matrix of ‘times, spaces, gestures and relations’ that these ‘larger’ things are realized. Put di erently, the theatre of social life is performed on the stage of the quotidian; it is on the platform of the mundane and the sensual that social dramas are rendered. In a chapter devoted to the body, Melucci observes, as he puts it, the ‘earthly consistency’ of emotions, ‘fed as they are by moods and sounds, by odours and vibrations. Fear and joy, tenderness and sorrow are not merely ideas but tears and laughter, warmth and trembling’ (1996b:72).

In this book I have sought to illuminate but a few of the ways in which music features in this life-web. My aim has been to delve into the matter of how music is constitutive of agency, how it is a medium with a capacity for imparting shape and texture to being, feeling and doing. I have tried to show how music works in this regard through specific circumstances and for particular individuals. Moving between so-called ‘normal’ and ‘disabled’ individuals, across settings and life stages, I have tried to show that music is not about life but is rather implicated in the formulation of life; it is something that gets into action, something that is a formative, albeit

Music as a resource for human being |

153 |

often unrecognized, resource of social agency. In this final chapter I want to dwell upon the matter of how music works, how its powers come to be harnessed for and converted into action, and how this process can help to illuminate our understanding of social agency.

‘Sleepers awake’ – music as a resource for human being

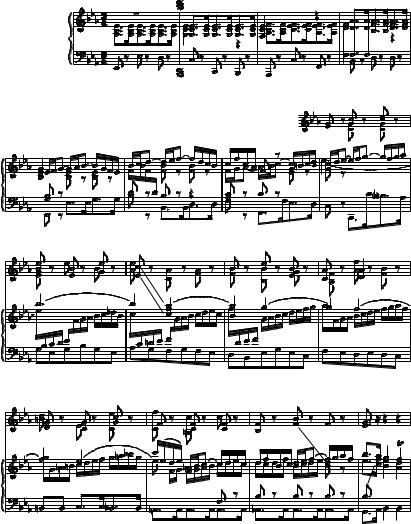

In 1731 J.S. Bach wrote the famous cantata, ‘Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme’ (BWV 140) for the twenty-seventh Sunday after Trinity. The opening of this work exhorts those who have been sleeping to ‘wake up’ and quickly join the procession of the Trinitarian King. Underpinned by dotted – agitated? – rhythms, the sopranos sing the three-syllable message (‘Wachet auf’) on three sustained notes of the E flat major triad, and this tonally centred, authoritative ‘call’ is underpinned by a busy counterpoint of the altos, tenors and basses and a ‘rushing’, forward-moving obliggato in the treble instrumental accompaniment. (The opening is illustrated in figure 7.)

The metaphor of using music to call ‘sleepers’ to action is apposite. For agency is perhaps the opposite of social ‘sleep’. To possess agency, to be an agent, is to possess a kind of grace; it is certainly not merely the exertion of free will or interest. It is, rather, the ability to possess some capacity for social action and its modes of feeling. Judith Butler makes this point clearly in her conceptualization of gender as an outcome of recurrent cultural performance, as the result of how actors mobilize cultural forms and discourses such as language. As she puts it, we need not ‘assume the existence of a choosing and constituting agent prior to language . . . there is also a more radical use of the doctrine of constitution that takes the social agent as an object rather than the subject of constitutive acts’ (1990:270–1, emphasis in original). To be an agent, in the fullest sense, is thus to be imbued – albeit fleetingly – with forms of aesthesia. Feeling and sensitivity – the aesthetic dimension of social being – are action’s animators; they give action and actors a life spark and a particular energy shape that burns, like a comet or a firecracker, for a time and along a trajectory or path. Following the etymological sense of the word, to be aestheticized is to be capacitated, to be able to perceive or to use one’s senses, to be awake as opposed to anaestheticized, dormant or inert. It is also to be awake in a particular manner, to possess a particular calibration of consciousness, an embodied orientation and mode of energy, a particular mixture of feeling. It is in this sense, then, that aesthetic materials such as music a ord perception, action, feeling, corporeality. They are vitalizing, part of the process through which the capacity to articulate and experience feeling is achieved and located on a social plane, how it is made real in relation to self and other(s).

154 |

|

Music’s social powers |

|

|

|

|

Corno |

|

Ob. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ob. I, II |

|

|

|

|

Taille |

|

|

|

Viol. picc. |

|

|

|

|

|

Viol. I, II |

Str. |

|

|

|

Va |

|

|

|

|

Continuo |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ob. II, III |

|

|

|

|

Viol. II |

|

5 |

Viol. I |

Ob. I |

Va |

|

|

Ob.I |

||

|

|

|

||

9

13 |

Va |

Figure 7. Johann Sebastian Bach, Cantata BWV 140, ‘Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme’

What, then, does it mean to speak of entering into or identifying with music such that one may become aestheticized? If music is a ‘quickening art’, then how does it work? And how does an understanding of music’s mechanisms of operation help to advance sociological conceptions of agency? To address these questions properly requires consideration of how our very concept of social order and its basis is historically specific.