Political Theories for Students

.pdf

OVERVIEW

Although the goal of almost every political system or theory is peace, many thinkers and politicians regard pacifism as an unrealistic strategy for achieving that end. International peace, they argue, can only be attained by a combination of hard–headed diplomacy and military preparedness. Domestic peace, they claim, will only be achieved with a strong police force and a tough court system. Pacifism, say many thinkers, belongs not in the domain of politics but in the realm of religious ideology. At best, pacifists are seen as hopeless idealists or as otherworldly dreamers. Thus, pacifism is recognized in standard political philosophy by its rejection.

Very often, pacifism is equated with passiveness, even though there is no linguistic link between the two words. Therefore, the application of pacifism, or anything approaching pacifism, is regarded as disastrous. Mention the word “pacifism” and Neville Chamberlain’s (1869–1940) failed effort to appease Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) at Munich is recalled and condemned as an example of what happens when real world leaders move too far in the direction of pacifism. Ironically, even some pacifists agree that pacifism has little practical value. They present the concept as a religious principle or a political ideal to be followed regardless of practical consequences.

Many modern–day pacifists see the world quite differently. They insist that peace, stability, and justice can only be attained by linking means and ends.

Pacifism

WHO CONTROLS GOVERNMENT? Officials supported by

the people

HOW IS GOVERNMENT PUT INTO POWER? Peaceful

removal of unjust regime

WHAT ROLES DO THE PEOPLE HAVE? Protest peacefully

unjust laws or actions

WHO CONTROLS PRODUCTION OF GOODS? The people

WHO CONTROLS DISTRIBUTION OF GOODS? The people

MAJOR FIGURES Mohandas Gandhi; Martin Luther

King Jr.

HISTORICAL EXAMPLE U.S. civil rights movement in 1960s

2 5 3

P a c i f i s m

CHRONOLOGY

700–600 B.C.: Isaiah begins to envision a kingdom based not on military might but on peace and humility.

c. 563–483 B.C.: Siddhartha, who became known as the Buddha, is said to have discovered the path to Truth.

c. 30 A.D.: Jesus of Nazareth is executed by the Romans.

395: Augustine is made Bishop of Hippo.

1647: George Fox begins the Society of Friends or Quakers.

1828: Leo Tolstoy develops a strong pacifistic critique of the evils of oppressive power and violence.

1948: Mohandas Gandhi is assassinated.

1950s: Martin Luther King, Jr. uses the principles of pacifism to gain civil rights for African Americans.

1960s: Gene Sharp develops the model of Civilian Based Defense.

1968: Martin Luther King, Jr. is assassinated.

1994: Aung San Su Kyi is placed under house arrest for using nonviolent Buddhist principles to challenge the non–democratic government of Burma.

1994: The new South African constitution contains provisions for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Thus, the way to achieve peace is to do peace. Pacifism holds that war and violence are circuitous paths to peace at best and dead ends at worst. Today, after a century that witnessed trench warfare, the atomic bomb, the Holocaust, and genocide, there is a renewed willingness to consider the merits of pacifism as a practical political theory with applications for the real world. Pacifism, its supporters content, can combine both peace and power. Pacifists note that some of the great political gains of the twentieth century resulted from nonviolence. The independence of India, the civil rights victories in America, and the liberation of East-

ern Europe from the Soviet Union came through nonviolent means. The leaders of those movements used nonviolent techniques to exert great pressure on unjust political and social systems. For those leaders and their followers, nonviolence was a strategy for bringing about change that in former times would have been sought through violent revolution.

While at the international level, most people still consider force to be the most reliable means of protecting national interests and preserving the peace, pacifist theorists have started to offer credible alternatives. Nuclear pacifism, international law, and civil- ian–based defense are three ideas that reject conventional strategies for maintaining order at the global level. Nonviolent methods of national defense, say pacifists, save lives, are more democratic, cost less, may work better, and are environmentally friendly. When looking at ways of keeping order within a nation, pacifists suggest new and nonviolent ways of dealing with criminals, handling ethnic disputes, and managing community conflict. Not only do pacifists recommend their nonviolent strategies as cheaper and less painful, they also argue that nonviolence can be more effective.

HISTORY

Pacifism as a theory began with religious rather than with explicitly political thinkers. In India, Jainism (sixth century B.C.) and Buddhism (third century B.C.) stressed strict self–mortification and purification that rejected the passions that led one away from God, Truth, or Enlightenment. Of all the human passions, violence was regarded as the most dangerous. The eighth–century B.C. prophets of Ancient Israel and, later, Jesus in the first century, proclaimed a pacifism rooted in the idea that all people are children of one God, in the concept of divine mercy, and in the belief that love could transform enemies. Later, in the seventh century, the prophet Mohammed (570–632) preached a religion that prohibited violence and exploitation within the community of faith (Islam) and against taking innocent lives in any situation.

Although the first Christians were probably non–violent, by 180 A.D. a few Christians served in the Roman army. With the conversion of Emperor Constantine I (288–337) to Christianity in 312 A.D., pacifism declined in importance. In fact, once Christians were in the majority and Christianity became the official state religion, Christians came to believe that they had a duty to defend both the faith and the empire with force. Augustine, Bishop of Hippo

2 5 4 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

P a c i f i s m

(354–430), advocated the use of force against the heretical Donatists. On a philosophical level, in his book The City of God, Augustine argued that inner motives were more important than external behavior. In his view, Christians could wield the sword so long as their hearts were fixed on God’s Kingdom rather than on self–promotion and self–protection.

Pacifism in the Medieval World

In the medieval world, the ideal of pacifism was all but abandoned by Christians and Muslims. Inquisitions, crusades, and jihads were sanctioned as examples of obedience to God. The brave knight or the warrior–martyr were honored as God’s most obedient servants. Pacifism continued to exist as an ideal, but only in marginalized form. Monks, holy men, and priests might be expected to live a life of pacifism, but anyone holding a position of responsibility within the state was expected to exercise force against heretics, ordinary criminals, and external enemies. When, in the late Middle Ages and early part of the Reformation, radical Christians such as the Waldensians or Anabaptists called on Christians to reject any type of violence, they were hunted down, tortured, and executed. Their pacifism was regarded as a grave danger to a society that did not distinguish between loyalty to the church and obedience to the state. In the seventeenth century, when followers of George Fox (1624–1691), founder of the Society of Friends, called on the faithful to reject the use of violence, they were reviled and persecuted.

The early modern era continued to reject the concept of pacifism. In the turbulent years marked by religious wars and succession struggles, pacifism seemed wildly irrelevant, even dangerous and immoral. As authoritarian rulers in Europe brought order and built nations, military might was regarded as a fundamental element of every successful state. When authoritarianism gave way to democracy at the end of the 1700s, violent revolution was seen as the liberating tool of the masses.

Events in the world of politics were paralleled by developments in the intellectual world. Generally, pacifistic ideas were not considered seriously by political thinkers. They regarded pacifism as an unrealistic concept that had little application in the real world. The best way to prevent violence, they argued, was to exercise violence against those who posed a threat. Nevertheless, even within the ancient world, there were some restrictions on violence. Babylonian, Hebraic, and Roman law outlined guidelines that required fair treatment of lawbreakers and placed limits on the conduct of warfare. Concepts such as “an eye for an eye” prevented violence from spinning into an

escalating cycle of vengeance and retaliation. Much of this thinking about limits was codified in the “Just War Theory” supported by the Church. Underpinning these laws and guidelines was the common sense concept of fairness and the realization that violence must be monopolized by the state if it was to be contained within manageable proportions. In practice, that meant that revenge and unlimited retaliation were controlled by placing them in the hands of recognized governments exercising force in a dispassionate and predictable manner. In practice, that also meant that revolution against a government, however unjust, was generally not sanctioned.

Pacifism into the Twentieth Century

With the Enlightenment and the subsequent emergence of nineteenth–century liberalism, political idealists began contemplating a world in which human beings would rise above the barbaric and outmoded practices of warfare. The future, they believed, belonged to wise pacifists. Heartened by the great progress they observed in the scientific and technical worlds, these thinkers assumed that improvements in the political and moral realms were equally possible. In their view, advancements in the area of international law and international organizations would replace the need to resolve conflicts with violence. In spite of powerful contrary evidence such as the American Civil War, colonialism, and World War I, this hope was sustained. Optimism about the ability to end war and resolve conflict peacefully reached a high point in the 1920s. Treaties to limit or ban the use of weapons and the founding of the League of Nations suggested that humans could exchange the brutality of armed combat for the civilized procedures of the courtroom and international government. The dream of a world federation uniting all nations and people of the world did not seem like an unrealistic vision. Nevertheless, the prospects that pacifism would become an acceptable political ideology vanished as liberalism crumbled under the onslaught of twentieth–century human tragedy.

The 1920s ended with a debilitating global recession that called into question the ability of humans to manage the economy. Furthermore, racism and imperialism, previously regarded as positive or, at least, acceptable values, began to be regarded as evil and dysfunctional. Italian dictator Benito Mussolini’s (1883–1945) invasion of Ethiopia, Japan’s advances into Manchuria and southeast Asia, Hitler’s incursion into Poland, the Holocaust, the Allied forces’ carpet bombing of German cities, and the American use of the atomic bomb all shattered the last vestiges of liberal pacifism. On the other side of the ideological

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 5 5 |

P a c i f i s m

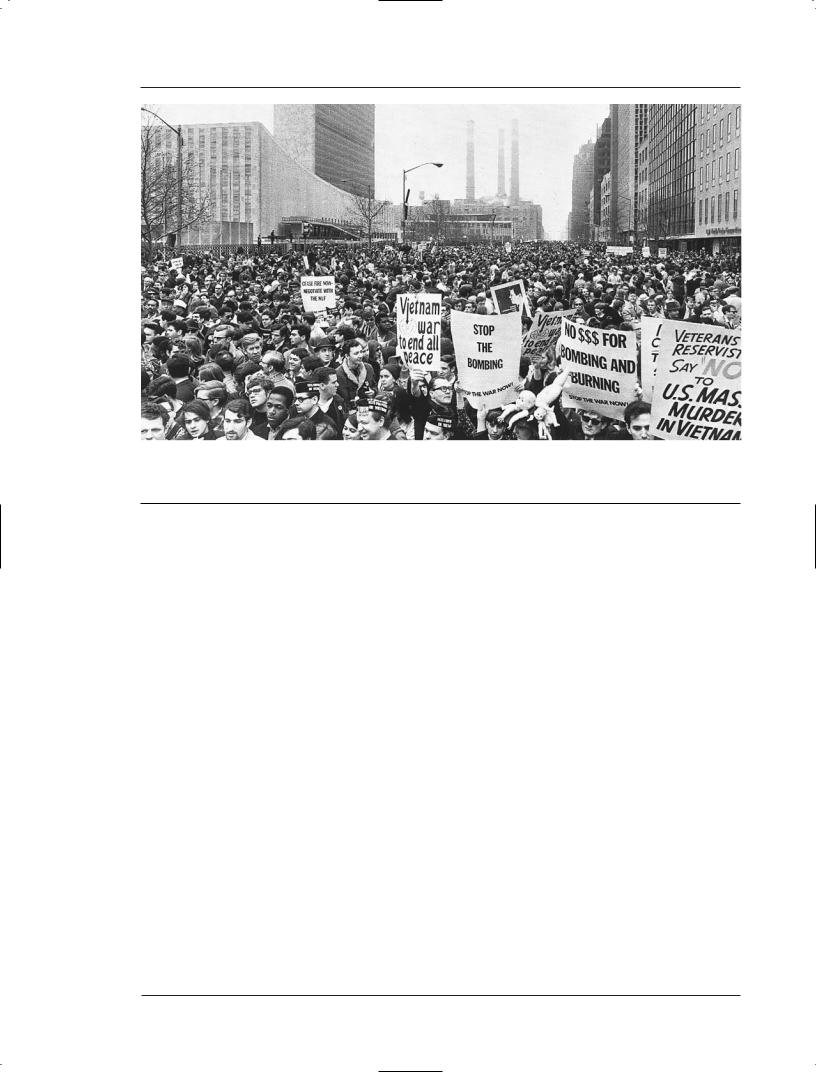

Anti-war protesters holding a peaceful demonstration against the Vietnam War at United Nations Plaza.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

spectrum, evidence from the Soviet Union suggested that a communist revolution to create a worker’s utopia had degenerated into a police state. Clearly, education, idealism, discussion, and goodwill would not be enough to solve the deep–seated social, economic, and political problems of the world. In the darkest days of World War II, some began to doubt that the humane ideals of liberalism and democracy were robust enough to counter the militaristic machinations of nazism, fascism, and bolshevism.

By the mid–1930s, leading Western pacifists were abandoning their earlier optimism. The American Reinhold Niebuhr (1892–1971), formerly a prominent pacifist, denounced political pacifism as dangerous and religious pacifism as morally irresponsible and spiritually self–righteous. The superlative evils of totalitarianism could only be countered with the lesser evil of force being exercised by nations and individuals who reluctantly but courageously recognized their obligation to challenge tyranny.

Nevertheless, by the time the twentieth century drew to a close, it was evident that pacifism had made great progress. In Asia, Mohandas K. Gandhi (1869–1948) had employed nonviolence to gain independence for India in 1947. Then, in the 1950s and 1960s, Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929–1968), used

nonviolent methods to make significant inroads into racial segregation in the United States. In part, King succeeded because “White America” feared King’s more radical counterparts such as militant black leader Malcolm X (1925–1965). However, it is clear that King’s nonviolence, which he credited to Gandhi and to Jesus, was the key factor in transforming race relations in America. By 1960, most of the African continent had broken loose from European colonialism. The leading figure in this movement, Kwame Nkrumah (1909–1972) of Ghana, was a firm believer in Gandhi’s technique of nonviolence. Motivated by practical political considerations, Nkrumah recognized that nonviolent protest was more effective against the colonial masters than violent confrontation. While violent protests would be put down quickly, nonviolent action would be much more difficult to deal with because of political and moral constraints on the British.

The Vietnam War

Nonviolent protest was also used in Europe and North America to challenge and change the prevailing political agenda. In the United States, nonviolent activists forced the Lyndon Johnson (1908–1973) and Richard Nixon (1913–1994) administrations to end the Vietnam War. The activists regarded the war as an ex-

2 5 6 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

P a c i f i s m

tension of French colonial activities in Southeast Asia. While some protesters such as Daniel (1921– ) and Philip (1923– ) Berrigan, both Catholic priests, were motivated by religious conviction, others such as Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) operated on the basis of moral or political belief. Nonviolent protests included refusing to register for the draft, holding sit–ins and teach–ins on university campuses, fleeing the country to take refuge in Canada, withholding taxes designated for military operations, breaking into draft board offices, and entering military sites to attack weapons of mass destruction in a symbolic fashion. The Berrigan brothers were at the forefront of those resorting to dramatic acts of prophetic protest and civil disobedience against a political system they considered anti–human. In Vietnam itself, devout Buddhist pacifists such as Thich Nhat Hanh worked to alleviate the suffering of victims on both sides of the conflict. Many Buddhists were killed by both the communists and anti–communists who wanted people to take sides instead of identifying with the displaced and dying of both political camps.

Following the Vietnam War, pacifist activists continued their protests while shifting their focus. Now, they challenged the enormous build–up of nuclear weapons in the world. Groups such as Greenpeace called attention to environmental degradation, which they labeled “ecocide.” Pacifists criticized the way powerful northern hemisphere nations oppressed people of the third world. Pacifists also opposed the use of the death penalty in countries such as the United States. Often they challenged laws and customs limiting the rights and privileges of minorities, women, and homosexuals. Paradoxically, these same activists generally did not oppose abortion, saying that support for the rights of women to control their own bodies took precedence over the very weak rights of the unborn. Ironically, the strongest opponents of abortion were often vigorous supporters of a strong national defense and of the death penalty.

The Counterculture

While a number of pacifists were committed to a counterculture vision and to counterculture protests, others operated within mainstream religious or political institutions. In Europe, the Green Party, with a pacifistic agenda that included a call for social justice, the rejection of nuclear weapons, and respect for the environment, was able to gain enough support to become a serious opposition group. In the United States, churches and civic groups were successful in getting some courts to incorporate alternative approaches to civil and criminal justice and in pressing Congress and the Executive to give more attention to the environ-

ment, human rights, third world development, and nuclear issues. In response to pacifistic concerns, both the State Department and the Defense Department attempted to explain military operations such as the invasions of Granada, Panama, and Kuwait in “Just War” terms. In Japan, strong pacifist sentiments limited the size, scope, and strategies of the Japanese military and resisted deploying or storing nuclear weapons on Japanese soil.

Pacifism and the Fall of Communism

In the 1980s, the political and military hold of the Soviet Union crumbled. Many military strategists insist that the Soviet Union fell because it was unable to withstand the relentless military competition from the West. But, other analysts credit the peaceful protests of the Eastern Europeans for the demise of the Soviet Empire. Starting with Polish labor leader Lech Walensa’s (1943– ) nonviolent Solidarity Movement, Eastern Europeans threw off Soviet rule. While the Soviets would have responded with crushing force to any violent uprising, they were less certain about how to deal with peaceful citizen protests. In the end, the Soviet Empire was defeated, not by the heavy long–range missiles of the United States, but by the millions of ordinary citizens who engaged in nonviolent protest against their Communist governments. Even in China, where an authoritarian remained in power at the end of the twentieth century, the greatest challenge to the regime came from a peaceful protest at Tiananmen Square in 1989. Symbolic and nonviolent challenges such as the Goddess of Democracy erected by students and the actions of a single unarmed man who managed to stop a tank riveted the attention of the world and forced the central government to reevaluate its policies. The nonviolent strategies of the Tiananmen protesters probably were more effective against the authoritarian regime than any armed confrontation would have been. In Myanmar (formerly Burma), political leader Aung San Suu Kyi (1945– ) resorted to nonviolent hunger strikes to challenge the authoritarian government that ruled her nation. Although still not successful at the end of the twentieth century, she won a Nobel Prize for her nonviolent strategy. Another Nobel Peace Prize went to South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu (1931– ) for his efforts to bring about a peaceful end to the Apartheid regime. Drawing on his African heritage and his Christian principles, Tutu had consistently advocated confession, forgiveness, restitution, and reconciliation as the best way to deal with injustice.

As the twentieth century drew to a close, the value of nonviolence as a political strategy was recognized by a number of governments that incorporated certain

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 5 7 |

P a c i f i s m

MAJOR WRITINGS:

Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy 20:5–8: When you go to war. . .the officers shall say to the army: “Has anyone built a new house and not dedicated it? Let him go home, or he may die in battle and someone else may dedicate it. Has anyone planted a vineyard and not begun to enjoy it? Let him go home, or else he may die in battle and someone else enjoy it. Has anyone become pledged to a woman and not married her? Let him go home or he may die in battle and someone else marry her. Then the officers shall add, ”Is any man afraid or faint–hearted? Let him go home.

The principles of Deuteronomy are that the enjoyment of life takes precedence over the pursuit of war, that people should not be compelled to fight, and that the tactics of war must be limited.

nonviolent strategies into their national policy. Several Scandinavian countries developed plans to use nonviolence as a method to deter and resist invasion. And, in the United States, Congress funded the U.S. Institute of Peace, whose mission was to study and promote non–lethal methods of conflict resolution. In part, the motivation for establishing the Institute was to assuage critics of traditional hard–line diplomatic and military strategies and, in part, the motivation was a revival of the old tradition of progressive liberalism. However, the main motivation was the desire to find cheaper, more durable, and less destructive methods of dealing with conflict. To achieve that end, the Institute was willing to consider strategies advocated by pacifists.

THEORY IN DEPTH

Pacifists who rely on religious teachings for support must deal with the obvious contradictions contained in their religious traditions. Christians, Muslims, and Jews must come to terms with the fact that the Old Testament and the Qur’an sanction holy war and jihad, thus validating violence as a cultic activity and religious obligation. Hindus must acknowledge that the Ghagavad Gita regards war as a duty. Jainists

and Buddhists must deal with the fact that their pacifism is intertwined with a strong rejection of worldly passions and desires in a way that is sometimes offensive to modern people. Furhter, proponents of African Traditional Religion recognize that their gods often are mobilized to support battles against enemies.

The Old Testament

The Old Testament, a foundational document for Jews, Christians, and Muslims, sometimes supports the concept of using violence so long as it is contained within the structures of the state. But, pacifists remind modern readers that the early Hebrews and their neighbors practiced a tribal religion in which the gods fought for their people. The total destruction of enemy tribes was the norm and at the end of every skirmish, no matter how minor, boasting warriors claimed to have annihilated hundreds and thousands of their opponents. Later, Hebrew monotheism challenged that xenophobic tribal view. Stories of battles, handed down through oral tradition, were reshaped to downplay the role of human warriors. Thus, the Exodus is said to have occurred without even one Hebrew killing an Egyptian. In fact, the human hero of the battle was Moses whose primary activity was to hold up his staff while the divine hero, God, destroyed the Egyptian army. Years later, the hero Gideon defeated the Midianite army after sending the vast majority of his warriors home. According to the Book of Judges, the explanation for Gideon’s bizarre strategy was to prevent Israel from claiming victory instead of recognizing the power of God. At the watershed battle of Jericho, the Hebrews limited their activity to rituals such as blowing trumpets and shouting as they marched around the heavily fortified city. When walls of that previously invincible city fell, human warriors could take no credit. In his final speech, Israel’s greatest warrior of all, Joshua, retold the story of the conquest of the land. Joshua reminded the people that God, not they themselves, had won the battles.

As Hebrew law and theology were codified in writing sometime after the tenth century B.C., the militaristic tenor of earlier thought was challenged even more. Deuteronomy, Israel’s law book, outlined rules for the conduct of war and explained the provisions for excusing men from military service. Anyone who had been engaged to be married, built a house, or planted a vineyard was exempt. Deuteronomy even released men who feared going into battle. Furthermore, the book required that combatants not destroy fruit trees even if such destruction would lead to victory.

2 5 8 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

P a c i f i s m

Israel’s prophets and writers of the Psalms (songs), developed a strong theology of nonviolence and a vision of God’s faithful kingdom. In fallen temporal society, the worship of idols, the use of magic and sorcerers, the exploitation of the poor, a reliance on foreign military alliances, and the use of horses and chariots were all condemned as undermining faith in a single–minded and singular God. In the eighth century B.C., the prophet Hosea explicitly linked militarism and injustice when he said, “You have plowed iniquity, you have reaped injustice, you have eaten the fruit of lies because you trusted in your chariots” (Hosea 10:13). When envisioning God’s triumphal final kingdom, a symbolic way of explaining the goal of creation, the prophets presented a portrait of peace and justice; the seventh–century prophet Isaiah described an idyllic time when even predation in the animal kingdom would cease (Isaiah 65). More concretely, in the sixth century B.C., the preacher Zechariah described the Messiah, God’s anointed servant/king, as victorious in humility and peace.

The Teachings of Jesus

The life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth (c. 4 B.C.–c. 29 A.D.) were strongly supportive of pacifism. Jesus specifically called on his followers to show love to their enemies, to turn the other cheek when attacked, and to practice mercy and forgiveness. Jesus supported his teachings by grounding them in the very nature of God. Thus, he linked nonviolent love to the most fundamental reality of the universe. Christian pacifists such as John Howard Yoder (no relation to the author of this essay) note that Jesus’ message was all the more remarkable because he lived in an occupied country that had a long history of violent political confrontation. When Jesus proclaimed himself God’s Messiah (anointed king) he was identifying himself with the temporal liberation of the nation of Israel. The clarity of that message was obvious to his Jewish contemporaries. His disciples looked forward to a political victory. Almost to the end of Jesus’ life, James and John expected to sit on thrones when he achieved victory. And at least one, and perhaps as many as four, of his twelve disciples belonged to a radical and violent revolutionary group called the Zealots. While the actions of several disciples are all we have to suggest that they were adherents of that group, the name of one, Simon the Zealot, established the point beyond doubt. Jesus’ messianic claim was obvious to the Romans who executed him for sedition. On his cross, they placed the inscription “King of the Jews.”

While conventional wisdom and theology expected a warrior messiah, Jesus reinterpreted that vi-

Jesus Christ preaching the Sermon on the Mount.

(Archive Photos, Inc.)

sion. The Kingdom he promoted would be based on principles of compassion, generosity, and forgiveness. Thus, he would rule over a community held together by love and humility rather than violence and power. In perhaps the most dramatic demonstration of this vision, he made his triumphal entry into Jerusalem riding on a lowly donkey, an animal of the common people and a beast of toil, not on a horse, a symbol of military might and royal prestige. In modern times, his action would be equivalent to participating in a state parade riding in a used car instead of standing in an attack tank or an armored limousine.

Pacifism and Muslim Thought

Muslim thought, although less explicitly peaceful than Christian doctrine, can be used to support some elements of a pacifistic philosophy. Muslim theology begins with the unequivocal affirmation in the one God, Allah, who created an orderly universe. The duty of both humans and nature is to surrender or submit (Islam) to Allah. As God’s agents on earth, humans have an obligation to live in obedience. God, who is merciful, gives humans the capacity to follow his will and create a just and orderly society. While not condemning state force, the Qur’an denounces tribalism and economic exploitation. Since there is only one God who created all people, there can be only one hu-

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 5 9 |

P a c i f i s m

BIOGRAPHY:

Lala ’Aziza

The Islamic commitment to peace was exemplified by Lala ’Aziza, “Our Lady of Goodness,” a devout Moroccan Muslim who lived in the mid–1300s. A teacher and doer of good works, she was highly renowned as a peacemaker. Not only did she mediate conflicts between opposing tribal groups, she challenged a powerful governor/general who was determined to conquer her region. Walking out alone to meet the warring general, she risked her life to speak of God’s demands for justice and to explain the sin of hurting God’s creation. Convinced by Lala ’Aziza’s religious arguments, the general retreated, leaving her town untouched and untaxed. After her death, ’Aziza’s tomb became famous as a place of refuge and reconciliation. Since then, no bloodshed or any type of violence has been permitted at the site and the attendants offer protection to anyone seeking refuge from attack or capture.

man race. In the faithful Islamic community, all stand before God in equality. All who submit to God are brothers and sisters. In the Mosque, when men and women are at prayer, there is no distinction based on wealth, race, class, or family standing. All pray directly to God. No one needs an intercessor whose special knowledge, authority, or stature sets him or her apart and above.

Pacifism in Asia

In Asia, Jain Dharma, an Indian religion generally known as Jainism, has been one of the most important sources of pacifism. Jainism attributes its origins to a series of heroic victors (Jinas). The last and greatest of these heroes, Var–dhamana, supposedly lived in the sixth or fifth century B.C. Renouncing great wealth for self–mortification, he is said to have died of starvation after fasting in order to free himself from this life. Jains hold that karma, the accumulated good and evil humans have done, binds people to an endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. Through complete asceticism, best exemplified in ahimsa or complete nonviolence, the soul is released and self is

extinguished. The strictest adherents of Jainism go to great lengths to take no life, even the lowest forms. They wear veils to avoid inhaling and killing insects, and they eat only foods such as milk, fruit, and nuts that can be consumed without destroying the life of the donor organism. Jains avoid violence in any form because violence is the most powerful way to accumulate negative karma and be attached more firmly to this life. In fact, negative karma may do more than require that one remains trapped in the cycle of life, death, and rebirth; it may lead the self into an even lower stage in the following life.

Hinduism contains many concepts similar to those in Jainism. Also originating in India, but somewhat later, many of its concepts are contained in the Bhagavad Gita. Through pure thoughts and actions, Hindus seek to be released from the cycle of existence. Renouncing all selfish desires, Hindus avoid both pleasure and pain, sensations that bind one to self and to this world. Although neither Jainism nor Hinduism insist that their followers practice pacifism at a governmental level, both religions had an important influence on the thinking of Mohandas Gandhi, the most famous pacifist of the twentieth century.

Buddhism Buddhism is another powerful Asian voice that has sometimes been used in support of pacifism. According to tradition, Buddhism began with Siddhartha (c. 563–483 B.C.), a wealthy young man born into a family of warriors in northeast India. After having married and fathered a son, Siddhathra renounced the comforts of his home to search for the peace of Nirvana, an escape from the pain of repeated existence. He was disappointed to find that extreme asceticism including self–punishment did not help him achieve his goal. Instead, he discovered that quiet contemplation involving concentration and focused meditation enabled him to grasp the truth. Thus, he became the Enlightened One or the Buddha. For the remainder of his life, he taught his followers the Four Noble Truths that lead to truth or enlightenment. Rather than being a negative religion or philosophy that renounces this life, Buddhism is a positive thought system promising that human beings can attain both moral understanding and moral improvement. The first of the Four Noble Truths recognizes the universal reality of suffering. At a social level, this can be interpreted as a call on people to empathize with the pain and deprivation of the less fortunate. The second Noble Truth identifies craving, lust, and desire as the cause of suffering. This teaches people that selfishness and ambition lie at the root of evil and misfortune. The third Noble Truth states that suffering and pain can be ended, but only if people turn away from

2 6 0 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

P a c i f i s m

efforts to dominate, accumulate, and seek only their own pleasure. Finally, the fourth Noble Truth outlines the concrete steps one must take to achieve enlightenment. Among these steps are admonitions against ill–will, cruelty, harsh language, lying, sexual exploitation, theft, or killing. Although most often applied at an individual level, many Buddhists have used these admonitions to provide guidance for political leaders. In modern times, individuals such as the Dalai Lama (the title of the leader of Tibetan Buddhism) and Thich Nhat Hanh (1926– ) have relied on Buddhist thought to construct a pacifist philosophy for political conduct. What is consistent in the ideas of all Buddhists is the strong emphasis on inner qualities and a correct moral attitude, and there is less attention to political strategies or techniques. A good and wise leader will do the good. A leader lacking deep inner moral grounding, no matter how skilled and shrewd that person may be, cannot be trusted to govern peacefully.

While religion has provided the foundation for many pacifists, logic and reason have been the guides for other advocates of nonviolence. The Greek and Roman Stoics developed theories calling for extreme self–control that enabled people to rise above human passion and pain. Keenly aware of the multi–ethnic nature of human society, the Stoics called for a community that accepted all people, no matter what their origin, as having equal worth and dignity. Such values contributed to the development of pacifist theories and practices based on the inherent rationality and equal value of all human beings.

Best known as a Christian thinker, Augustine Bishop of Hippo (354–430) mainly drew on classical logic and on Roman legal concepts to develop his theories regarding peace. As a Neo–Platonist, Augustine believed the universe was constructed in a manner so that every element seeks rest in its natural place. Augustine held that peace, in a static, orderly form, was an intrinsic quality of all existence. Even robbers and warriors, he wrote, long for peace. Turning to the world of politics, Augustine promoted the Just War Theory, a concept outlined earlier by the Roman Stoic Cicero (106–43 B.C.).

Just War Theory

Although not a doctrine of pacifism, the Just War Theory does place important limits on the conduct of war. As developed later by the Catholic Church and accepted by Protestant thinkers, the doctrine requires that combatants act only under the authority of a legitimate rule (Just Authority). Thus, rebellion or revolutionary violence is prohibited. The Just War Theory also insists that warfare is never legitimate unless there is an actual, not just a potential, threat (Just

Sculpture of Buddha. (Corbis Corporation)

Cause). Furthermore, the theory holds that the belligerents must not expand their goals once war begins (for example, not shift the intent from defense to conquest) and that the central aim of any war should be a peaceful resolution and a restoration of harmonious relations (Just Intention). These three principles (just authority, just cause, and just intention) are generally classified under the category of jus ad bellum, or law before war. Warfare, once it begins, must adhere to rules know as jus in bello, or law during war. These guidelines, also known as Just Means, are intended to protect non–combatants and their property, to prohibit inhumane methods of combat, and to outlaw a dis-

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 6 1 |

P a c i f i s m

Henry David Thoreau. (The Library of Congress)

proportionate response to an injury. Along with the Peace of God, a medieval injunction similar to Just Means, and the Truce of God, a medieval regulation restricting the days when war could be conducted, the Just War Theory attempted to sharply limit the conduct of war. While all of these ideas were associated with the Church, they were in fact based on principles of reason and logic first proposed by the Romans.

Reformers

From the Middle Ages until modern times, pacifism has been relegated to more marginal religious movements and utopian thinkers. Authorities both in the dominant Catholic and Protestant Churches and in the emerging nation states all assumed that the use of force and violence were essential for the maintenance of social order. Reformers such as Martin Luther (1748–1826) and John Calvin (1509–1564) held that since God had created human society and the state, God expected Christians to participate in the military. In France and England, Catholic and Anglican thinkers supported similar ideas. Only groups such as the Anabaptists and the Society of Friends called on individuals and governments to renounce the use of force. In contrast to Catholic and mainline Protestant thinkers, they saw the fourth–century conversion of Constantine and the establishment of Christianity as the official state religion as the fall of the faith. In the view of paci-

fists such as the Anabaptists, there was no way to reconcile New Testament teachings with the sword of the political kingdom. The Anabaptists insisted that fidelity to the peaceful example of Jesus was the central tenet of Christianity. Thus, people and individuals using violence stood outside God’s will. Even the use of force against invading armies or against heretics, regarded at that time as traitors to the state, was not legitimate. The Society of Friends, or Quakers, who focused on the idea that God indwells all human beings, regarded war and violence as a violation of the high value of people regardless of race, nationality, gender, or station in life. In colonial America, William Penn (1644–1718) attempted to implement Quaker ideals in his newly founded Pennsylvania.

Secular proposals for national or world systems based on the principles of pacifism emerged during the Enlightenment. One of the most persuasive and carefully developed was contained in the writings of the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). In his book Perpetual Peace, published in 1795, Kant argued that no state had a right to invade or acquire another state. Unlike property that could be exchanged in the market, a state is a society of free human beings that no one has a right to rule or dispose. Kant held that standing armies would eventually be abolished. Linking militarism with authoritarianism, Kant said that a free and democratic society would not consent to war that was costly both in its implementation and aftermath. What free people, he asked, would willingly accept losing their lives and property for the sake of fighting? Although Kant recognized that pacifism was not likely to be accepted soon, he believed that the unifying power of global commerce guaranteed the eventual establishment of perpetual peace.

Henry David Thoreau

The American transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) based his argument for pacifism on his devotion to radical democracy and on his faith in the innate ability of all humans to know the truth. Thoreau stands as a champion of the idea that the claims of the state can never take precedence over the moral authority of individual conscience. The state, therefore, had no right to use force to compel or control. In his essay “Civil Disobedience” Thoreau argued that states tend to be oppressive and parasitic. War, in his time the American invasion of Mexico, and official support for slavery proved to Thoreau that the government was unable to act in a virtuous manner. As a result, Thoreau insisted that people cannot turn over their moral responsibility to others. According to Thoreau, the individual must always follow his or her conscience, even if that means disobeying the law. Not

2 6 2 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |