Political Theories for Students

.pdf

N a t i o n a l i s m

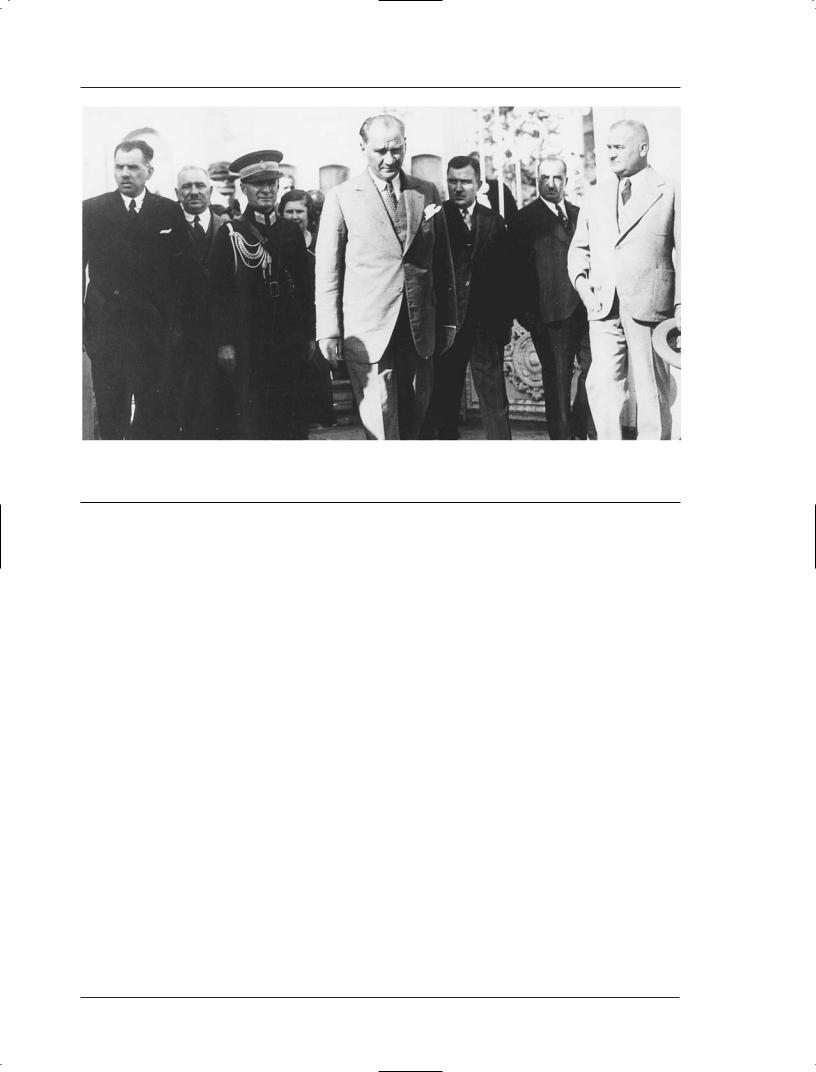

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (center), heading for the celebration of the ninth anniversary of the Republic of Turkey.

itive directions, sometimes in ways harmful to the group. As the casino dilemmas reveal, long–standing conflicts between Native American nations and the United States over issues of sovereignty, land rights, and rights to economic resources are far from being settled and in fact have become more complicated over time.

Atatürk and the Modernization of Turkey

In the early years of the twentieth century, Turkey was governed by the Ottoman Dynasty, formed during the expansion of control by the Ottoman caliph (leader of Islam) some six hundred years earlier. Straddling Europe and Asia, Turkey was still a primarily agrarian country, a composite of ethnic groups as varied as the Ottoman Turks and the nomadic Kurds, a stateless people living in several countries. Having emerged as a military hero among Turks in 1915 while the rest of Europe was embroiled in World War I, Mustafa Kemal (1881–1938) led the Turkish liberation struggle beginning in 1919 against Ottoman rule, a campaign that culminated in independence for the Republic of Turkey in 1923.

Born to Ali Riza, his father—a customs official who later became a merchant but died while Mustafa was still a child—and to Zubeyde, his mother, who

single–handedly raised Mustafa and his sister after his father’s death, Mustafa grew up in the former Ottoman city of Salonica, now a city in Greece. Enrolled at first in a traditional religious school then educated in a modern school, and afterwards in a military high school, Mustafa Riza was given the name Kemal— “perfection”—by one of this high school teachers in honor of his high scholastic achievement. After graduating from the War Academy in 1905, Mustafa Kemal and his compatriots fought and successfully deposed the Ottoman sultan in 1908, the beginning of an illustrious military career for the future president of Turkey.

After the Republic of Turkey was proclaimed, with Mustafa Kemal as its first president, Mustafa proceeded to implement widespread reforms throughout the various sectors of the Turkish government and society. During his fifteen–year reign as president, Mustafa—who was renamed “Atatürk” (“Father of the Turks”) in 1934 by the Turkish Parliament when legislation was passed requiring everyone to adopt a sur- name—managed to modernize Turkey more quickly than had ever been done in any other state. Reforming the political, social, legal, economic, and cultural sectors of Turkey, Atatürk secularized the government and the education system, granted women equal rights

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 4 3 |

N a t i o n a l i s m

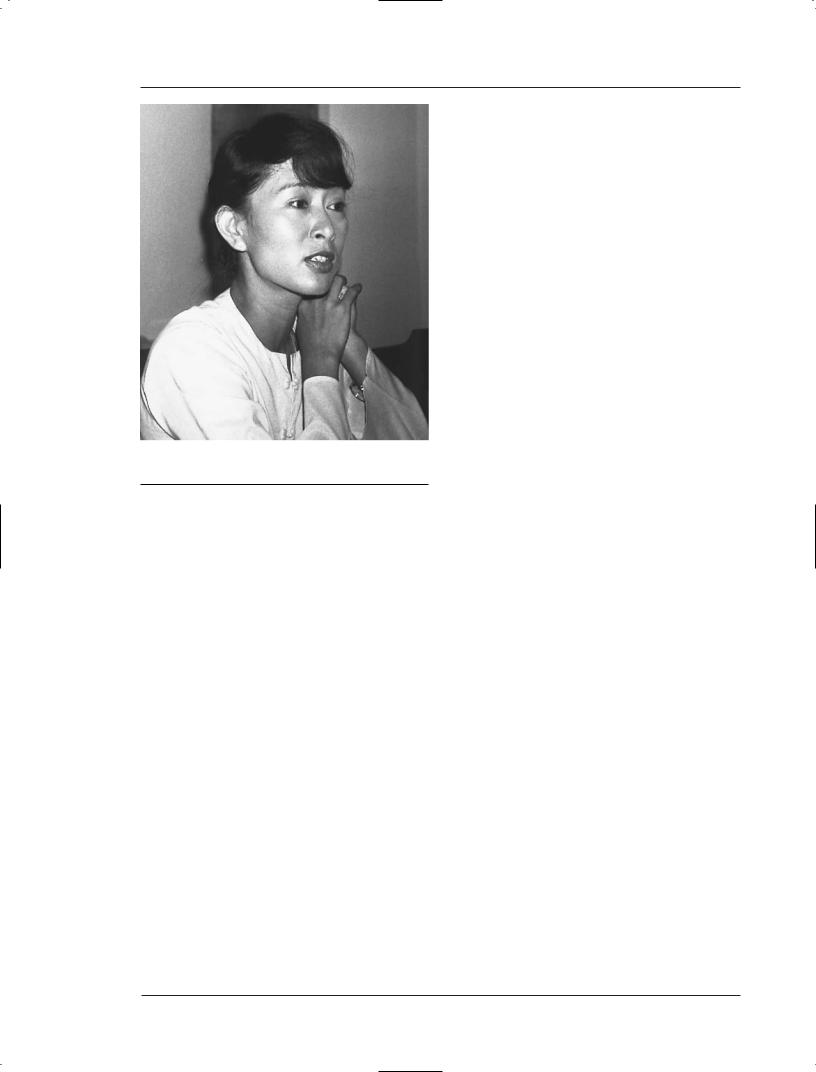

Aung San Suu Kyi. (Corbis-Bettmann)

with men (including full political rights), converted the Arabic script–based alphabet used in Turkey to a new Turkish alphabet based on Latin script, shifted Turkish dress from traditional Middle Eastern garb to Western–style clothes, and promoted the arts, sciences, agriculture, and industry.

A charismatic leader, Atatürk exemplified the type of leadership around which a new national identity could be formed and for which a nation could be mobilized to achieve remarkable conquests in such fields as health, education, and diplomacy in a very short time. Recognized by the League of Nations for his commitment to world peace, Turkey’s first president led the way for Turkey to be invited to join the League in 1932. And by encouraging his people to reshape their national identity in more modern directions, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk facilitated Turkey’s transformation into a society which by century’s end would be preparing itself for entry into the European Union.

Aung San Suu Kyi and the

Democratization of Burma

Northwest of Thailand and Laos and tucked in just south of India and China, the country of Burma (renamed “Myanmar” by the military government that captured state power in 1988) is a country with a long history of efforts toward democratization. Colonized

by the British, Burma achieved independence in 1947. Just before the transition to independence was to take place, however, a bloody military coup toppled those who rightfully should have assumed power—most prominently Burma’s national hero, Aung San, who had assisted the Allies in their fight against the Japanese in World War II. Aung San would have become Burma’s first president had he and most of his prospective cabinet not been assassinated by a jealous general bent on seeking this position for himself. Just two years earlier, Aung San’s daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi, had been born.

Though she does not recall much about her father since he died when she was only two years old, Aung San Suu Kyi reports having been inspired by her father’s reputation and image. A formidable Burmese leader in her own right, Suu takes after her father in her charismatic ability to draw supporters to the cause of human rights and democracy in Burma, despite— or perhaps in part, because of—her status as a prisoner of conscience. Suu was placed under house arrest in 1989 by the military junta who took over after the previous national leader, Ne Win, resigned in July 1988.

Educated in England at Oxford University, Suu had returned to Burma in 1988 to care for her dying mother. Apparently unwittingly, she arrived at just the right time to organize a democratization campaign among Burmese anxious to see an end to fifty years of military rule. Beloved by her supporters, encouraged by the international human rights community, and assisted by Burmese grassroots activists, Suu has pursued a non–violent campaign of resistance to Burma’s military rulers and has worked to build a democratic future for Burma where democratic political participation will finally be possible.

The political strategy followed by Suu and her fellow members of the National League for Democracy, the party she quickly founded in 1988, has been one of non–accommodation to the demands of the junta—the State Law and Order Restoration Committee (SLORC)—coupled with persistent encouragement for non–violent protests and the promotion of democracy and human rights. In 1989 Suu was placed under house arrest by the military junta, who feared the growing success of her democracy movement and Suu’s increasing popularity as an active political force. While under house arrest, Suu and her party won the national election of 1990. Although Suu rightfully should have assumed the presidency of Burma after her election, this was blocked by the military junta. In 1995, Suu was released from her house arrest. Matters intensified when a pro–democ-

2 4 4 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

N a t i o n a l i s m

racy uprising at the University of Yangon was crushed by the military in 1998. Additionally, Suu’s sentence was reimposed in September 2000, when Suu was accused of leaving Rangoon to participate in a political event.

The winner of the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize, Aung San Suu Kyi was honored and the cause of democracy in Burma was promoted by the Nobel Laureates attending the annual Peace Prize ceremonies in Oslo, Norway in the fall of 2001 and the special ceremonies commemorating one hundred years of the Prize. Recognizing Suu’s achievements with a special letter of support directed toward Burmese military leader Than Swe, the Nobel laureates in early December 2001 requested the Burmese government to release Suu from house arrest and to negotiate with her for democratic reforms. In October 2000 Suu began secret, UN– facilitated talks with the Burmese military junta to secure the release of other political prisoners, and within one year about two hundred prisoners were released. Aung San Suu Kyi reportedly is optimistic that her talks with the junta will lead to progress for the Burmese people. As she stated in a videotaped message released in the year 2000, “We are absolutely confident that democracy will come to Burma.” Suu’s campaign to build a solidaristic union of Burmese citizens committed to the values of democracy, human rights, and non–violence appears to be gradually paying off.

Flooding Nubia, Submerging a Nation

The ancient African nation of Nubia, situated along the Nile River in what is now southern Egypt and the northern part of the Sudan, is a five–thousand–year–old civilization whose relics from the past include exquisite rock carvings, temples, monuments, painted tombs, and buildings of stone. Once the rival of ancient Egypt, Nubia conquered Egypt around 700 B.C. The Nubian kingdom continued to flourish several centuries into the Christian era, its black kings continuing to rule from their capital city of Meroe. Although most Westerners seem to know little about Nubia, this African archaeological treasure boasted more pyramids in the Sudan than Egypt had. Furthermore, the oldest city yet discovered in Africa is one being excavated in Nubia at the turn of the new millennium.

By the early twentieth century, however, the Nubian nation was threatened with cultural extinction. As Egyptian engineers sought solutions to the problem of severe water shortages in Egypt due to population growth along the Nile and the need for greater sources of water for agricultural cultivation, a plan was devised to dam the Nile and create a reservoir of water. Damming the Nile River at Aswan, the Egyptian gov-

ernment completed the first Aswan Dam in 1902 and heightened it twice in the three decades that followed. Again in the early 1960s, a second Aswan Dam was built, again flooding the Nubian national homeland. When much of their land was flooded as the dam was built and the Nile was redirected, thousands of Nubians were forced to relocate to Cairo or to Khartoum, the Sudanese capital. Lower Nubia was submerged, along with many monuments from antiquity not saved by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) salvaging campaign prior to the flooding.

The displaced Nubians have traveled to Cairo and Khartoum and farther, reaching the United States and Europe in their quests for new homes after Lower Nubia was flooded. Among those forced to migrate was Hamza El Din, born in Troshka, Nubia (Sudan) in 1929. Trained as an electrical engineer in Cairo, where he had moved when Nubians began to migrate, El Din took up the oud, a stringed wooden instrument—the Arabic predecessor of the European lute—after graduating from the university. Formally shifting his career to music, El Din studied in Italy and later returned to Nubia, traveling by donkey to collect traditional Nubian folk songs. El Din invented a unique blending of Nubian rhythms and sounds with Arabic and contemporary music, harmonizing musical elements across cultures.

Visiting the United States in 1964, El Din participated in the Newport Folk Festival and his career in music took off. He began recording his original combinations of Nubian–Arabic music. Using music as his vehicle to achieve recognition for the plight of the Nubian nation, its forced migration, and the tragic disappearance of the Nubian landscape, El Din has performed throughout the world and recorded several albums of his Nubian–Arabic musical synthesis. The first Nubian musician to become known in the West, El Din has been vocal about the tragedies suffered by the Nubian nation and the damage to the natural environment and ancient cultural treasures of Nubia.

In 1998 the Sudanese Minister of Irrigation and Water Resources, Sharif al–Tuhami, announced the Sudanese state’s plans to construct three new hydroelectric dams on the Nile. One of these, the Hamdab High Dam, would be located in Nubia at Merowe at a cost of up to 1.5 billion dollars. El Din in 2001 was continuing to play an active role in the shaping of international consciousness surrounding Nubia and the ancient land’s destiny. Alerting the world of the Sudanese government’s plans to replicate the efforts of the Egyptians by constructing additional dams along the Nile that would completely flood Nubia, including the few remaining ancient treasures of the Nubian

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 4 5 |

N a t i o n a l i s m

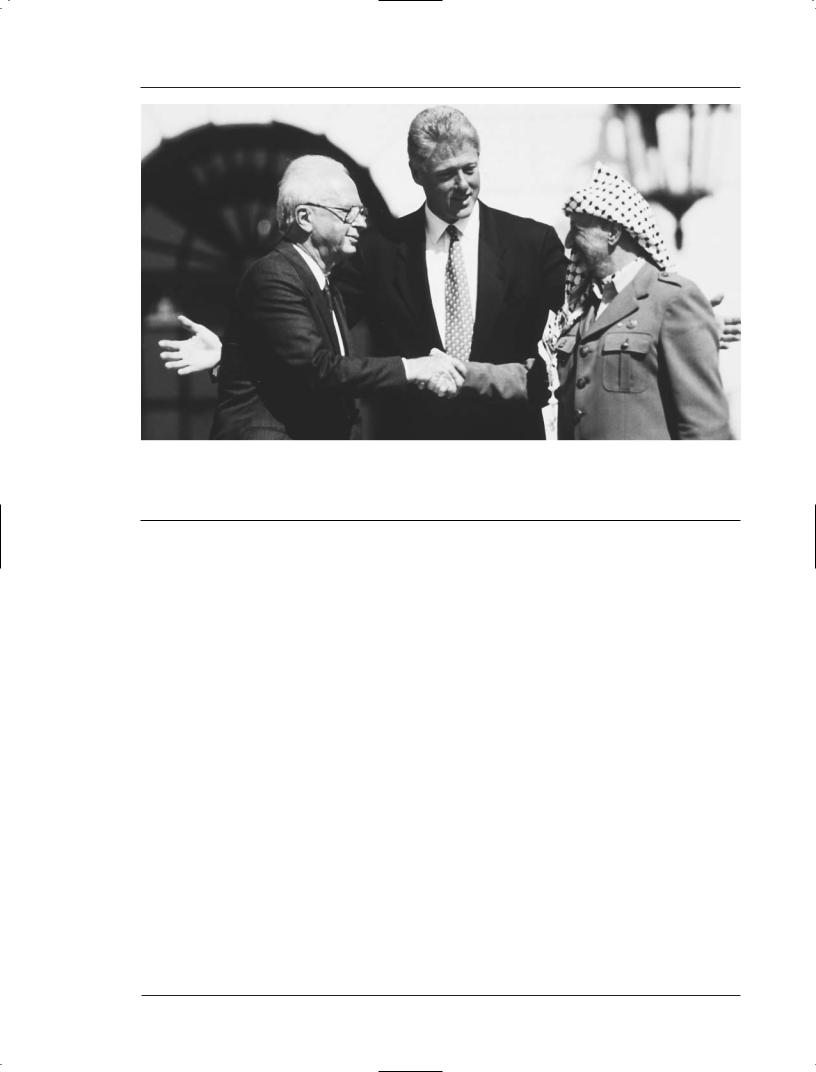

Numerous attempts at peace between Israel and Palestine have been made, often facilitated by the United States. Here, U.S. President Bill Clinton (center) watches as Palestinian Yasser Arafat (right) and Israeli Yitzhak Rabin shake hands after signing the 1993 Oslo Peace Accords.

nation, El Din in 2001 continued to perform concerts in America, his homeland since 1968, and to participate in lectures concerning the land of Nubia and his music. Lacking state power, the Nubian nation is obliged to bring its concerns to the international community in hopes of securing assistance and support in its quest to save the last remaining traces of this ancient land from obliteration. The states of Egypt and Sudan literally have turned a deaf ear to the pleadings of Hamza El Din and others intent on preserving the ancient Nubian culture and carrying the Nubian nation’s rich heritage into the twenty–first century.

Creating Israel, Denying Palestine?

Authorized by UN Resolution 181 of 1947, the State of Israel was created out of territory belonging to what had been known for a quarter century as the British mandate for Palestine, an area placed under British control by the Council of the League of Nations in September of 1922. Near the end of World War I, the British had issued a statement of support for a Jewish state in Palestine through the Balfour Declaration. The Declaration of November 2, 1917, issued as a letter written by Arthur James Lord Balfour, British Foreign Secretary at the time, to the British Lord Rothschild, was a formal declaration of sympa-

thy on the part of the British king and cabinet with the Zionist Federation, whose goal was the creation of an Israeli state in the Middle East. Although it remains somewhat unclear as to why Britain issued this declaration, speculation has it that Britain wished to win the support of Jews for the ongoing war effort in Europe.

With the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, a move sanctioned by UN General Assembly Resolution 181 of November 29, 1947, some 780,000 Palestinians lost their homes and were forced to migrate out of Palestine, as their villages were destroyed. Over the next fifty years the Palestinians would become the largest stateless dispersed population in the world, with some 3.7 million Palestinians officially registered with the UN at the turn of the new millennium, including the descendents of the original Palestinian refugees, and countless more Palestinians internally displaced—that is, living near their original homes but unable to return. About one–quarter of the 1.3 million Palestinian citizens living in Israel by 2001 were internally displaced persons. Treated by the Jewish state as second–class citizens, the Palestinians lacked full participatory rights in the political structures of Israel and were subject to discrimination in employment, housing, and other sectors of their daily lives.

2 4 6 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

N a t i o n a l i s m

Although the Jewish people, too, had been denied a homeland for centuries following their expulsion from the heart of the Middle East, the creation of the State of Israel after World War II without the simultaneous creation of a State of Palestine was viewed by many—both Palestinians and non–Palestinians—as a disastrous course of action. While in 1947 the Palestinians had the right to accept a separate state for themselves, based on UN Resolution 181, they rejected this offer, hoping to secure a more favorable solution. For the next fifty–plus years, the Middle East would be embroiled in religious and ethnic conflict, heating up at times into active wars or simmering at a lower but still deadly temperature. Since the 1980s low– intensity warfare taking the form of the Intifadah waged mostly by Palestinian boys and youths and more virulent attacks on Israel by extremist groups such as Hamas, coupled with the intense aggression of the Israeli military, have produced a seething, seemingly never–ending conflict that has been extremely difficult to contain, let alone resolve.

At the turn of the millennium the continuous actions of extremist Jewish settlers intent on informally expanding the State of Israel by building Jewish homes on Palestinian territory (despite international prohibitions against such further encroachments on Palestinian land) have provoked additional violence on both sides and further complicated attempts to gradually cede territory to the Palestinians so they, too, may have their own state. Weaknesses in the creation and performance of the self–governing Palestinian Authority, the reluctance of Israel to fully withdraw from the Palestinian West Bank and Gaza Strip, the slow pace of diplomatic negotiations, and the lack of sufficient international pressure on both Israel and the Palestinian Authority to end the cycle of violence and establish greater security in the region have made it unlikely that full peace will be realized in this troubled region anytime soon.

International agreements and peacemaking efforts notwithstanding, the Palestinian–Israeli conflict over the right to establish a secure Israeli state, the right of Palestinians to return to the land of their or their ancestors’ birth and to claim their own state, and the right for both Jews and Arabs, let alone Christians, to live in and govern Jerusalem, regarded as an especially holy city by Muslims, Jews, and Christians alike, has proven to be one of the thorniest international conflicts in modern history. Key problems associated with this entangled conflict have revolved around the inconsistent recognition of Palestinians and Jews as distinct nations deserving full territorial and political rights, including control of a state. When stateless peoples like the Palestinians and (formerly)

the Jews contest claims over the same piece of territory, arguing from historical memory that each merits a stake in the territorial pie, if not the whole pie, then a peaceable, just outcome will be very difficult to achieve. Exemplifying the problems inherent in conflicting claims to national territory and the right to a sovereign state, the Palestinian–Israeli conflict will not be easily resolved in the near future, despite the number of scholars who have theorized about national identity–building and the construction of the nation.

Ghana

Kwame Nkrumah (1909–1972), known by many as the “Father of African Nationalism,” became the first president of the independent West African nation of Ghana in 1960. He shared his esteemed title with the American black socialist leader Marcus Garvey, who reportedly inspired much of Nkrumah’s thinking on the need for black–led independence movements in Africa and the African diaspora. Nkrumah wished to see the Gold Coast (as Ghana was called while governed by the British) independent and ruled by Africans themselves. Ghana achieved internal self–rule in 1951 and in March 1957, became the first sub–Saharan African state to step out from under the yoke of European imperialism. (On December 24, 1951, Libya became the first North African state to attain independence—and like Ghana, from British rule.)

Nkrumah’s early life Born in 1929 among the Akan people in the village of Nkroful in Nzimaland, the far southwestern area of the Gold Coast, Kwame Nkrumah trained for his first career as a teacher at the Prince of Wales College in Achimoto, just north of Accra. Inspired by the school’s Vice Principal, Dr. Kwagyir Aggrey, who had trained in America as an educator, Nkrumah grew convinced that the best means to improve the conditions of Africans’ lives was through education. Working to inspire his own students to develop their academic potential, Nkrumah began a number of literary clubs and academic societies for his students and became increasingly interested in discussing the political affairs of Africans with his colleagues at the Catholic school at Axim in Nzemaland, where he served as headmaster. The failure of indigenous Africans in the Gold Coast in 1934 to successfully oppose a British Sedition Bill aimed at stopping the anti–colonial press, coupled with the growing resistance of African cocoa farmers to British exploitation of their industry, led Nkrumah to seek training in the disciplines that would allow him to contribute to the Gold Coast’s liberation campaign.

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 4 7 |

N a t i o n a l i s m

Kwame Nkrumah.

Moving to the United States in 1935, Nkrumah earned a Bachelor of Science degree in economics and sociology from Lincoln University in Philadelphia in 1939 and a Bachelor of Theology degree from Lincoln Theological Seminary in 1942. He also received a Master of Science degree in education plus a Master of Philosophy degree in 1945 from the University of Pennsylvania, where he completed significant work toward a doctorate in philosophy. Later in 1945, Nkrumah moved to London, where he soon began participating in twice–weekly discussion sessions at the home of Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda, an African also educated in America. Among the other attendees at these sessions were a raft of future African leaders, including Jomo Kenyatta (c. 1894–1978), Julius Nyerere (1922–1999), Kojo Botsio, and Harry Nkumbula. In London, Nkrumah also attended lectures at the London School of Economics and Political Science on politics and socialism, helped organize the West African national Secretariat, and began the Pan–African Movement, serving as Joint Secretary to the Fifth Pan–African Congress in Manchester, England, in late 1945. Building relationships with members of the British Parliament who were sympathetic to the cause of African liberationists and to socialism, Nkrumah laid the groundwork for his future political career, contributing articles to periodicals advocating independence for

African colonies and collaborating with George Padmore, a West Indian socialist writer and activist who also opposed colonial rule.

Formation of Ghana By the late 1940s Nkrumah and his compatriots were ready to challenge British control of the Gold Coast, a country rich in minerals and cocoa farms and ripe for revolution. Nkrumah believed, however, that an effective revolution could be waged only if the economic needs of the citizens of Ghana were appropriately addressed. His campaign to liberate the Gold Coast from British rule thus included advocating a form of socialist governance, a policy of “African Socialism,” whereby the state would own key industries and develop the national infrastructure along with social welfare programs to serve the needs of ordinary people. Nkrumah returned to his homeland in 1949 and founded the Convention People’s Party (CPP) with the goal of achieving immediate national independence. He was imprisoned for several months in 1950, having encouraged his fellow countrymen to participate in illegal strikes. After the Gold Coast was granted internal self–rule in 1951, Nkrumah served as prime minister from 1952 to 1957. When Ghana became a fully independent country in 1957, Nkrumah continued to serve as prime minister until 1960, when he became the country’s first president.

Although Nkrumah was initially welcomed as Ghana’s first president after independence, mismanagement and corruption under his rule led eventually to a tightening of power by Nkrumah and to very unwelcome restrictions on freedom of expression and freedom of association within the country. Courting support from the Soviet Union, Nkrumah took Ghana in increasingly socialist and authoritarian directions. In 1964 Nkrumah made Ghana a one–party state, led by his own CPP. His increasingly dictatorial style coupled with his failure to deliver on the economic and social benefits he had promised Ghanaians led to Nkrumah’s loss of power in a bloodless coup while he was visiting China in 1966. Nkrumah returned to West Africa to live in exile in Guinea until his death in 1972, serving as a co–head of state for Ghana during that time. One year after his death, Nkrumah’s reputation as one of the great political leaders of the period of African independence was restored.

Nkrumah believed that only a pan–African union of solidarity could ensure Africans true financial, social, and political independence and security. For this reason, Nkrumah led the way for the formation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, founded in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia after a conference involving thirteen African states and nineteen African

2 4 8 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

N a t i o n a l i s m

colonies soon to become independent. Greatly respected and admired by many of his fellow Ghanaians and by countless other Africans, Nkrumah sought to achieve economic self–sufficiency for the newly independent African nation–states through cooperative understanding and the creation of a genuine brotherhood of nations across Africa. Although his dream to unite Africans through a pan–African union was not realized in his day, Nkrumah’s contributions to the liberation movements that transformed Africa in the wake of World War II were arguably unparalleled. The twenty–first century may yet see a rejuvenation of interest in the pan–Africanism Nkrumah envisioned as common solutions are sought for such problems as interethnic violence, poverty, HIV/AIDS and other epidemics, and the lack of adequate infrastructure marking the sub–Saharan region. A newer, more–inclusive concept of nationhood encompassing the wide range of ethnic communities living in African states—in- spired by Nkrumah’s past efforts and achievements and by the more–recent accomplishments of his fellow Ghanaian, UN Secretary–General Kofi Annan— may in fact be part of the solution to the challenges facing this important region of the world.

ANALYSIS AND CRITICAL RESPONSE

Despite the reticence of some theorists to admit that nationalism is an appropriate subject for theoretical study, plenty of evidence exists—and scholarly arguments as well—that indicate national identity, na- tion–building, and nationalism are all suitable topics for theoretical analysis. Yael Tamir argued in his article, “Theoretical Difficulties in the Study of Nationalism,” that theories of nationalism are necessary for several reasons. In order for a respectful discourse to take place on nationalism and national movements and in order for the members of different nations to be able to appreciate and respect the differences in their concepts of national identity, the world needs theories of nationalism. This becomes especially evident when we examine some of the challenges presented by nationalism and the adherents of particular conceptualizations of what it means to be a nation.

As noted in the Macmillan Encyclopedia 2001, “While it was hoped that nationalism would make for peace, in practice it has often resulted in xenophobia, rivalry, oppression of ethnic minorities, and war.” Unfortunately, nationalism in both theory and action has produced both negative as well as positive conceptualizations and realities for countless individuals and groups throughout the world. In part, this is due to the

nature of nationalist claims, which tend to be exclusionary. Additionally, early nationalist theories may have failed to account for or to predict the rise in ultra–nationalist movements and violent sentiments that would appear on the world scene as national fervor developed to a heightened pitch or overzealous or misguided political leaders took the stage to direct domestic and international affairs in ways Herder, Fichte, and Renan perhaps never anticipated.

Shortcomings

Some scholars see the tendency to divide theories of nationalism into “ethnic” versus “civic” categories as a serious problem, claiming that this dichotomous depiction is inaccurate and lacks thoroughness. Others note that in discussing the “civic” nature of certain theories of nationalism, “civic” has erroneously been seen as synonymous with “liberal democratic.” While some scholars have argued that Hitler’s racist campaign to rebuild German national identity cannot properly be labeled “nationalist” because of Hitler’s sharp departure from democratic values, others point out that Hitler nonetheless did construct a view of national identity around a particular conception of na- tionhood—however distasteful and deadly that conception proved to be. Not all shared political values reflect liberal democratic notions.

Additionally, nationalism in many ways presumes certain conditions that perhaps no longer fit the reality of social and political life in the late–twentieth and early–twenty–first centuries, both in the developed world and in economically developing regions. For example, questions concerning the possible irrelevance, inapplicability, or imperfect agreement of nationalism to multicultural societies are being considered by a number of theorists in the new millennium. Third–World scholars, too, have found fault with nationalist theories’ tendency to overemphasize the perspective of Western scholars and to downplay the differences in national development that have occurred in developing regions. The Indian concept of nation has been attuned to the importance of both spiritual and material aspects, according to Partha Chatterjee and a concept of Indian cultural identity allegedly developed before Indians attempted to cast off English dominance and political control. However, many Western scholars have tended to view liberation movements in the developing world and the simultaneous development of national identities among colonized peoples purely as reactions to imperial control, not as independently constructed movements.

Several scholars also have remarked upon the somewhat questionable relevance of many nationalist theories in the late twentieth and early

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 4 9 |

N a t i o n a l i s m

twenty–first centuries to the needs and interests of indigenous and stateless nations. Seeking to broaden definitions of the nation and interpretations of national movements and claims, these scholars have remarked on the tendency of many theorists of nationalism to focus on the typical course of development followed by Western nations, while ignoring the differential paths of Fourth–World and stateless nations. To construct their own national identities and negotiate relationships with those who colonized them and set their territorial boundaries, generally without their consent, indigenous and developing nations deserve appropriate theoretical analyses that illuminate the specific conditions of their existence and development and the alternative notions of national identity that distinguish them from the dominant cultural majority.

Gender Politics

Gender politics and their relation to national iden- tity–building and nationalist movements also has been a neglected area of scholarship in this field. Although concepts of the nation have typically stemmed from notions of a patrie (fatherland) and its associated heritage, theorists of nationalism generally have failed to adequately question whether the conceptualization of a nation has a particularly male thrust. Few theorists have taken up the question of whether and how gender relations come into play in the creation of national identities and the waging of nationalist campaigns. Whereas women and men have both played key roles in pursuing the course of their nations’ development throughout the world, assuming indirect as well as direct roles in forging national identities and laying claims to state power, very few twentieth century writers in the field of nationalism have addressed how gender relates to nationalism.

As Ernest Renan remarked toward the close of his 1882 lecture at the Sorbonne, “Man is a slave neither of his race nor his language, nor of his religion, nor of the course of rivers nor of the direction taken by mountain chains. A large aggregate of men, healthy in mind and warm of heart, creates the kind of moral conscience which we call a nation.” Presumably, Renan also meant to include women in this discussion, although he neglected to say this directly. The implication is that men rather than women have built na- tions—a rather indefensible claim, considering the number of women over the centuries who have sacrificed sons, husbands, brothers, and friends to the violence involved in most nation–building efforts and the number of women who themselves have assumed key roles as political activists, social reformers, and educators of the members of new nations.

TOPICS FOR FURTHER STUDY

•What is the relationship between ethnic identity and nationalism?

•According to international law, to what extent are indigenous minorities, immigrants, and national minority groups permitted to rightfully advance claims of self–determination? Do some groups deserve their own territorial state more than others? Would the world be a more peaceful place if every nationalist movement were granted its own territorial space and the possibility of self– governance?

•To what extent did the American reaction to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon represent ultranationalist fervor stemming from what Michael Billig terms “banal nationalism”?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sources

Africa News Service. “Sudan Plans to Build Three New Hydroelectric Dams across the Nile.” September 8, 1998. News article published initially in Addis Tribune, September 4, 1998. Available at http://www.vitrade.com/sudan_risk/Egypt/980908_ 3_hydroelectric_dams_built.htm, December 17, 2001.

Agyeman, Opoku. Nkrumah’s Ghana and East Africa: Pan–Africanism and African Interstate Relations. London: Associated University Presses, Inc., 1992.

Ataturk.com. “Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, 1881–1938.” Accessed 11/15/01 at http://www.ataturk.com/index2.html.

Barnard, F.M. Herder’s Social and Political Thought: From Enlightenment to Nationalism. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965.

BBC News. “The Balfour Declaration.” BBC News, November 1, 2001. Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/uk/newsid_ 1632000/1632259.stm, December 17, 2001.

BBC News. “Peace greats urge Suu Kyi release.” BBC News, December 8, 2001. Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/eng- lish/world/asia–pacific/newsid_1699000/1699384.stm, December 9, 2001.

Breuilly, John. Nationalism and the State, 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, copyright 1982, 1985, 1993; published by University of Chicago Press in 1994.

Brody, Donal. “Kwame Nkrumah The Early Years 1909–1947.” Great EpicsTM Newsletter, Vol. 1 No. 7, October 1997. Great Epics Books, 2001. Available at http://www.greatepicbooks.com/ epics/october97.html, December 4, 2001.

Brown, David. Contemporary Nationalism: Civic, ethnocultural and multicultural politics. London: Routledge, 2000.

Callison, James P. and University of Oklahoma Law Center. “The Iroquois Constitution.” Available at http://www.law. ou.edu/hist/iroquois.html, December 2, 2001.

2 5 0 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

N a t i o n a l i s m

Chen, David W. and Charlie LeDuff. “Bad Blood in Battle Over Casinos; Issue Divides Tribes and Families as Expansion Looms.” The New York Times, October 28, 2001.

dassk.com. “Welcome to Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s pages.” Available at http://www.dassk.com/dawsuu.htm, November 15, 2001.

ebooks.whsmithonline.co.uk. “Nkrumah, Kwame (1909– 1972).” From The Hutchinson Family Encyclopedia. Helicon Publishing Ltd, 2000. Available at http://ebooks.whsmithonline.co.uk/ENCYCLOPEDIA/53/M0002453.htm, December 4, 2001.

Eley, Geoff and Ronald Grigor Suny, eds. Becoming National: A Reader. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. “Into Africa: Black Kingdoms of the Nile.” Available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/africa/ africa3.shtml, December 17, 2001.

Gellner, Ernest. Nationalism. New York: New York University

Press, 1997.

George–Kanentiio, Doug. “Iroquois at the UN.” (Originally published in Akwesasne Notes New Series, Fall 1995, Vol. 1 Nos. 3–4.) Available at http://www.ratical.org/many_worlds/ 6Nations/IroquoisAtUN.html, November 15, 2001.

Gittings, Bruce M. “The Declaration of Arbroath.” Available at http://www.geo.ed.ac.uk/home/scotland/arbroath.html, December 17, 2001.

Greenfeld, Liah. “Is Nationalism Legitimate? A Sociological Perspective on a Philosophical Question.” In Rethinking Nationalism, Canadian Journal of Philosophy Supplementary Vol. 22, eds. Jocelyne Couture, Kai Nielsen, and Michel Seymour (Calgary, Alberta, Canada: Canadian Journal of Philosophy, copyright 1996; first published 1998).

Hamideh, Abbas on behalf of Al–Awda/Palestine Right To Return Coalition. “Palestinian refugees’ right to return should be acknowledged by Israel.” OP–ED article. The Journal News (Westchester County, NY), December 10, 2001.

Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Available at http://www.snenatrons.org.

Ivison, Duncan, Paul Patton and Will Sanders, eds. Political Theory and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Jagan, Larry. “Signs of hope for Aung San Suu Kyi.” BBC News, December 9, 2001. Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/ english/world/asia–pacific/newsid_1699000/1699780.stm.

Jocelyne Couture, Kai Nielsen, and Michel Seymour, eds. Rethinking Nationalism. Canadian Journal of Philosophy Supplementary Vol. 22. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: Canadian Journal of Philosophy, copyright 1996, first published 1998.

Johansen, Bruce Elliott and Barbara Alice Mann, eds. Encyclopedia of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Kandogan, Eser. “Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.” Available at http://www.cs.umd.edu/users/kandogan/FTA/Ataturk/ataturk.h tml, November 15, 2001.

Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. “The Building of the First Aswan Dam and the Inundation of Lower Nubia: Images from the Collections of the Kelsey

Museum.” Available at http://www.umich.edu/kelseydb/Exhibits/AncientNubia/PhotoIntro.html, December 10, 2001.

Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. “Ancient Nubia: Egypt’s Rival in Africa.” Press Release. Available at http://www.umich.edu/kelseydb/Exhibits/AncientNubia/AncientNubiaPressRelease.html, December 10, 2001.

Kyi, Aung San Suu, ed. and with an introduction by Michael Aris, foreword by V. Havel. Freedom from Fear and Other Writings. New York: Penguin Books, 1991.

Mabry, Marcus, Michael Meyer, Lara Santoro, Tom Masland, and Joe Cochrane. “The Promise, the Peril: Special Report.” In Newsweek, December 17, 2001.

McClintock, Anne. “‘No Longer in a Future Heaven’: Nationalism, Gender, and Race.” In Becoming National: A Reader, eds. Geoff Eley and Ronald Grigor Suny (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

Macmillan Encyclopedia 2001. London: Market House Books

Ltd, 2000.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Israel. “The Mandate for Palestine: July 24, 1922.” Available at http://www.mfa. gov.il/mfa/go.asp?MFAH00pr0, December 17, 2001.

Oneida Nation. Available at http://www.oneidasfordemocracy.org.

Oxford English Reference Dictionary, The. Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 1996.

Poole, Ross. “National Identity, Multiculturalism, and Aboriginal Rights: An Australian Perspective.” In Rethinking Nationalism, Canadian Journal of Philosophy Supplementary Vol. 22, eds. Jocelyne Couture, Kai Nielsen, and Michel Seymour (Calgary, Alberta, Canada: Canadian Journal of Philosophy, copyright 1996; first published 1998).

Prager, Carol A. L. “Barbarous Nationalism and the Liberal International Order: Reflections on the ‘Is,’ the ‘Ought,’ and the ‘Can.’” In Rethinking Nationalism, Canadian Journal of Philosophy Supplementary Vol. 22, eds. Jocelyne Couture, Kai Nielsen, and Michel Seymour (Calgary, Alberta, Canada: Canadian Journal of Philosophy, copyright 1996; first published 1998).

Renan, Ernest. “What Is a Nation?” In Becoming National: A Reader, eds. Geoff Eley and Ronald Grigor Suny (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

Rosenberg, Dan. “Hamza El Din.” Available at http://www.afropop.org/explore/artist_info/ID/336/Hamza%20 El%20Din/, December 10, 2001.

Seymour, Michel with Jocelyne Couture and Kai Nielsen. “Introduction: Questioning the Ethnic/Civic Dichotomy.” In Rethinking Nationalism, Canadian Journal of Philosophy Supplementary Vol. 22, eds. Jocelyne Couture, Kai Nielsen, and Michel Seymour (Calgary, Alberta, Canada: Canadian Journal of Philosophy, copyright 1996; first published 1998).

Shenandoah, Audrey. Haudenosaunee Delegation at the United Nations, Millennium World Peace Summit (August 28–30, 2000), Address by Audrey Shenandoah, Clan Mother, Onondaga Nation. Available at http://www.peace4turtleisland.org/pages/haudenosauneedelegation2000.htm, November 15, 2001.

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 5 1 |

N a t i o n a l i s m

Simpson, Audra. “Paths Toward a Mohawk Nation: Narratives of Citizenship and Nationhood in Kahnawake.” In Political Theory and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, eds. Duncan Ivison, Paul Patton, and Will Sanders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Smith, Anthony D. “The Origins of Nations.” In Becoming National: A Reader, eds. Geoff Eley and Ronald Grigor Suny (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

Tamir, Yael. “Theoretical Difficulties in the Study of Nationalism.” In Rethinking Nationalism, Canadian Journal of Philosophy Supplementary Vol. 22, eds. Jocelyne Couture, Kai Nielsen, and Michel Seymour (Calgary, Alberta, Canada: Canadian Journal of Philosophy, copyright 1996; first published 1998).

Williams, Kristen P. Despite Nationalist Conflicts: Theory and Practice of Maintaining World Peace. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2001.

Wilson, Woodrow. “Fourteen Points” speech before the Joint Session of the U.S. Congress, January 8, 1918. Available at http://www.lib.byu.edu/rdh/wwi/1918/14points.html, December 10, 2001.

www.ratical.org. “The Six Nations: Oldest Living Participatory Democracy on Earth.” Available at http://www.ratical.org/ many_worlds/6Nations/index.html, November 15, 2001.

Yahoo.com. “Hamza El Din–Biography.” Available at http://musicfinder.yahoo.com/, December 17, 2001.

Zuelow, Eric G.E. E–mail conversations with Barbara Lakeberg Dridi, October—December 2001.

Zuelow, Eric G.E. “The Nationalism Project.” Available at http://www.nationalismproject.org/, October 28, 2001.

Further Readings

BBC World Service. “The Nation State.” Available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/africa/features/storyofafrica/ 14chapters4.shtml. Focusing on the development of independent nation–states in Africa after World War II, this site identifies some of the key African leaders of the anti–colonial liberation movements and includes audio clips of historic speeches.

Braveheart This film depicts the development of Scottish identity and of nationalism among the Scots in the early 1300s, including the War of Independence from England and the Scottish Declaration of Arbroath of 1320.

Encyclopedia of Nationalism, Volumes 1 and 2. Editor– in–Chief, Alexander Motyl. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 2000. This encyclopedia contains a range of theoretical articles and case studies pertaining to nationalism, covering all regions of the globe.

Kanatiiosh. “Welcome to Peace 4 Turtle Island.” Copyright 2001. Available at http://www.peace4turtleisland.org/. Excellent collection of pages related to Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) contemporary affairs and history, including links to books about the Haudenosaunee.

Zuelow, Eric G.E. “The Nationalism Project.” Available at http://www.nationalismproject.org/. This site contains a wealth of resources and information related to the theoretical and practical study of nationalism.

SEE ALSO

Federalism, Imperialism

2 5 2 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |