grammatical foundations

.pdf

Structure

(12) |

S |

|

P |

|

P |

the |

postwoman pestered |

P |

the doctor

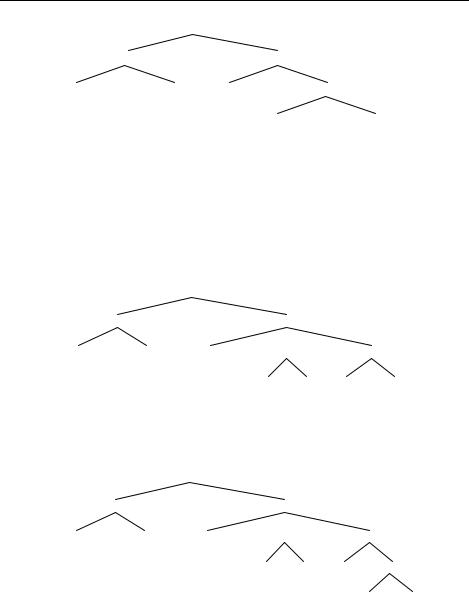

We see here that the sentence has even more internal structure as a phrase may also contain another phrase.

Indeed, once we recognise the notion of a phrase, we can see them in many positions. For example, a string consisting of the preposition on and its nominal complement Wednesday can be replaced by the noun yesterday demonstrating that they have the same distribution. Thus, on Wednesday is also a phrase in the sentence:

(13) the postwoman pestered the doctor [on Wednesday]/yesterday This suggests we have the following structure for this particular sentence:

(14) |

S |

|

|

|

P |

|

P |

|

|

the postwoman |

pestered |

|

|

P |

P |

||||

|

the |

|

doctor |

on Wednesday |

Moreover, in the phrase on Wednesday, the noun Wednesday can be replaced by the words his birthday, indicating that this is also a phrasal position:

(15) the postwoman pestered the doctor on Wednesday/[his birthday]

(16) |

S |

|

|

|

P |

|

P |

|

|

the postwoman |

pestered |

|

|

P |

P |

||||

|

the |

|

doctor on |

P |

his birthday

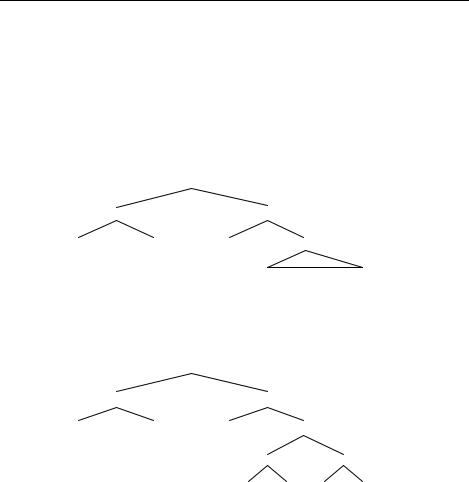

1.3Sentences within phrases

From what we have said so far we might think that English expressions are organised with sentences at the top, phrases in the middle and words at the bottom. Unfortunately things are not quite so regular. As we have seen, sentences can appear within sentences. A typical way for this to happen is to have a sentence as part of a phrase which itself is part of the bigger sentence. For example, instead of the phrase pestered the doctor in (12) we might have another phrase:

61

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations: Structure

(17)a the postwoman [pestered the doctor]

b the postwoman [thinks the doctor is cute]

The fact that we can substitute one phrase for another is an indication that they both are phrases as they both have the same distribution. But note, the new phrase in (17b) contains something that could stand alone as a sentence:

(18)the doctor is cute

Hence we have a phrase which contains a sentence. We can represent this situation easily enough, as in the following structure:

(19) |

|

S |

|

P |

|

|

P |

the |

postwoman |

thinks |

S |

the doctor is cute

Of course, this embedded sentence (traditionally called a clause – though some linguists do not use the terms sentence and clause with such a distinction these days) has its own internal structure made up of phrases and words and so the structure can be fully specified as follows:

(20) |

|

S |

|

|

P |

|

|

P |

|

the |

postwoman |

thinks |

S |

|

|

|

|

P |

P |

|

|

the |

doctor is |

cute |

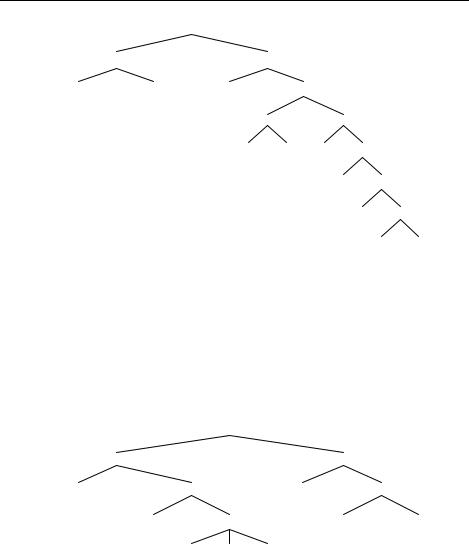

As we have mentioned, there is recursion in structure and so as sentences can contain phrases which themselves contain sentences, then these sentences can contain phrases which contain sentences – and so on, indefinitely. We will provide an example here with just one more level of embedding to give you some idea of how it works:

62

Structure

(21) |

|

S |

|

|

|

|

|

P |

|

|

P |

|

|

|

|

the |

postwoman |

thinks |

S |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

P |

P |

|

|

|

|

|

the |

doctor |

said |

S |

|

|

|

|

|

|

she |

|

P |

|

|

|

|

|

|

has |

|

P |

|

|

|

|

|

|

the |

flu |

So far we have looked at sentences which appear inside the second phrase of the main sentence, but this is not the only position we can find an embedded sentence. For example, we can find a sentence as the fist element of another sentence:

(22)a [the doctor] worried the postwoman

b [that she had a sore throat] worried the postwoman

In (22b) we have a sentence she had a sore throat introduced by the complementiser that. This sentence sits in a similar position to the phrase the doctor in (22a), in front of the verb. Thus, instead of this phrase, we can have a sentence, as in the following diagram:

(23) |

|

|

S |

|

|

S |

|

|

P |

|

|

|

|

P |

worried |

|

P |

that she |

|

||||

|

|

had |

P |

the |

postwoman |

a sore throat

Furthermore, we can have a sentence inside the first phrase of a sentence:

(24)[the diagnosis that she had the flu] worried the postwoman

Here, the diagnosis that she had the flu, is a phrase which contains the embedded sentence she had the flu, introduced by a complementiser that. The structure looks as follows:

63

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations: Structure

(25) |

|

|

|

S |

|

|

P |

|

|

|

P |

|

|

|

|

S |

worried |

|

P |

|

the diagnosis |

|

|||||

|

that |

|

|

P |

the |

postwoman |

|

she |

|||||

had P

the flu

Of course, this sentence could contain phrases that contain sentences and there could be other phrases elsewhere in the sentence that contain sentences. Hence very complex structures can be produced, though we will not exemplify these here for reasons of space.

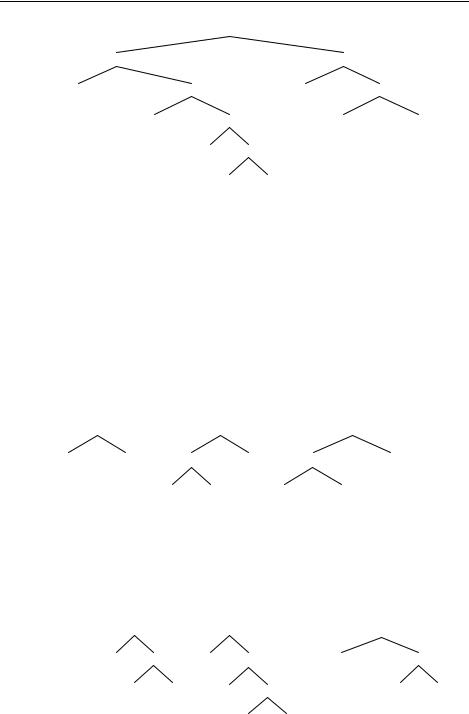

1.4Structural positions

The notion of structure helps us to define grammatical positions more easily. As we saw previously grammatical positions cannot be defined in terms of linear order. The verb, for example, might be the second, the third or indeed the nth element in a sentence, and yet there is still a definite position for the verb which no other element can occupy. Once we have introduced the notion of structure, however, we can see that the verb occupies the same structural position no matter what else is present in the clause.

Consider the following structures:

(26) |

|

S |

|

|

|

S |

|

|

S |

||

|

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

he |

snored |

man snored the |

old |

man snored |

||||||

Notice that in all these structures the verb occupies the same position inside the second phrase of the sentence. It would not matter how many words or other phrases the first phrase contained, the verb would still be in the same position with respect to its own phrase, and hence grammatical position defined in terms of structure is much more satisfactory than in terms of linear order. Moreover, if we consider the structure of the phrase that the verb appears in, we can identify its position within this phrase more easily than by counting its position in a linear string:

(27) |

P |

P |

|

|

P |

|

P |

|

||

|

|

|

kick |

P |

talk |

P |

surely |

|

|

P |

|

smiled |

saw |

||||||||

|

|

|

the |

cat |

|

to |

P |

|

the |

light |

|

|

|

|

|

|

the |

police |

|

|

|

64

Structure

Again, we cannot identify the position of the verb within the phrase in terms of linear order, but in terms of the structure it is clear that the verb always comes directly underneath this phrase, precedes its phrasal complements and may follow adverbial modifiers. As we proceed it will become even clearer that there is a unique structural position that verbs and verbs alone can occupy.

1.5Structural terminology

Now that we have introduced the notion of structure, we need some terms to use to refer to aspects of structures and the way we can represent them. The notion of structure entails that there are elements of a sentence that themselves are made up of other elements and indeed that these other elements may be made up of yet more elements, and so on and so on. The elements that make up a larger part of the structure are called its constituents and the constituents that directly make up a part of structure are called its immediate constituents. Thus, in a phrase such as the following, the verb and its complement phrase are its immediate constituents. Everything inside the complement phrase is a constituent of the whole phrase, though not an immediate constituent:

(28) |

P |

regret P

his decision

This kind of representation of grammatical structure is called a tree diagram, though unlike real trees, grammatical trees tend to grow downwards. The elements that make up the tree, the words and phrases etc. are called nodes and the lines that join the nodes are branches.

Finally, it is often useful to talk about two or more nodes in a tree and their relationships to each other. For this purpose a syntactic tree is seen like a family tree with the nodes representing different family members. For some reason however, these families are made up of women only. A node which has immediate constituents is called the mother of those constituents and the constituents are its daughters. Two nodes which have the same mother are sisters.

So to refer to the tree in (28) again, the top P node is the mother of the verb and the P node which represents the verb’s complement. The verb and the complement P node are therefore sisters. The complement P node is also a mother to the pronoun his and the noun decision and again these two nodes are sisters.

It would of course be possible to define the relationships ‘grandmother’, ‘aunt’, ‘cousin’ etc. for any given tree diagram. However these relationships tend not to be very important for syntactic processes and so we will not consider them.

There is another popular way of representing structure, which we have made some use of above without comment. This is the use of brackets to represent constituents. For example, the sentence we discussed above the postwoman pestered the doctor on his birthday can be represented as follows:

(29)[[the postwoman] [pestered [the doctor] [on [his birthday]]]]

65

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations: Structure

The way this works is that each constituent is surrounded by square brackets and so a constituent can be determined by finding an open bracket ‘[’ to its left and the corresponding close bracket ‘]’ to the right. Thus, the postwoman in (29) is defined as a constituent as it has an open bracket immediately to its left and a close bracket immediately to its right.

Admittedly, it is harder to see the structure of a sentence when represented with brackets than with a tree, as it takes some working out which open brackets go along with which close bracket. However, bracketings are a lot more convenient to use, especially if we only want to concentrate on certain aspects of a structure. So, for example, above we represented an embedded sentence using brackets:

(30)Kate claimed [Geoff jeopardised the expedition]

This partial bracketing demonstrates at a glance how the main sentence contains an embedded one and so bracketing can be a very useful way of describing simple structures.

The bracketing in (29) is not entirely equivalent to the tree diagram in (16) as in the tree the nodes have labels that tell us what they represent, phrases or sentences. We can add labels to brackets to make the two representations equivalent. With bracketing, the label is usually placed on the open bracket of the constituent:

(31)[S [P the postwoman] [P pestered [P the doctor] [P on [P his birthday]]]]

Again, this adds to the complexity of the representation and so it is not as clear as the tree diagram. But providing it is not too complex, it is still a useful way to represent structural details.

1.6Labels

Although we have been labelling phrases with the symbol P, not all phrases are equivalent to each other. This is best seen in terms of the distributions of phrases. Take, for example the two phrases in (16) the postwoman and the doctor. These look very similar, both consisting of a determiner followed by a noun. They also have the same distribution patterns, as shown by the fact that wherever we can put one of them we will also be able to put the other:

(32)a [the doctor] pestered [the postwoman] b I saw [the doctor]/[the postwoman]

c they hid from [the doctor]/[the postwoman]

As these phrases have the same distributions, we can assume that they are phrases of the same kind. However, not all phrases distribute in the same way. Consider the phrase on his birthday. This cannot go in the same places as those in (32):

(33)a *[on his birthday] pestered [the postwoman] b *I saw [on his birthday]

c *they hid from [on his birthday]

Clearly this phrase must be different from the previous two. We will see in the next chapter that the identity of a phrase is determined by one of the words it contains. This word is known as the head of the phrase. It will be argued later on in this book that the

66

Structure

head of phrases such as the postwoman is the determiner and the head of phrases such as on his birthday is the preposition. Thus, we distinguish between determiner phrases (DPs) and preposition phrases (PPs).

There are also other phrases associated with the verb (VPs), with adjectives (APs) and indeed with every kind of word category that we have discussed (noun phrases – NPs, inflectional phrases – IPs, CPs and degree adverb phrases – DegPs).

For now, the main point is that there are different kinds of phrases and these have different positions within the structure of the sentence and hence different distributions. We might therefore represent the sentence in (31) more fully as:

(34) |

|

S |

|

|

|

|

|

DP |

|

VP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

the |

postwoman |

pestered |

DP |

PP |

|

|

|

|

the |

|

doctor on |

|

DP |

|

|

|

|

|

his |

birthday |

We will not develop this any further at this point, and we will see that certain aspects of this structure are in need of revision. But the arguments for these developments will be given in subsequent chapters.

1.7Rules

The last thing we will mention in this section concerns the kinds of grammatical rules that could be responsible for producing structures such as in (34). Recall from the start of this section we introduced a formal rule which stated that sentences can be made up of words and other sentences:

(35)sentence → word*, sentence*

The rule states that a sentence is made up of some words and some sentences. Although this rule is not particularly accurate, we can see that this kind of rule is ideal for describing the kinds of structures we have been discussing, as they state what the immediate constituents of a structure are: in other words, this rule describes mother– daughter relationships.

From the structure in (34) it is possible to formulate the following rules:

(36)S → DP VP VP → V DP PP PP → P DP DP → D N

Such rules are known as rewrite rules as they describe how to draw a tree by ‘rewriting’ the symbol on the left of the arrow for the symbols on the right. Thus, if we start with the S at the top of the tree diagram we can rewrite this as a DP and a VP. The VP can be re-written as a verb, a DP and a PP and the PP as a preposition and a DP. The DPs can then be re-written as determiners followed by nouns.

67

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations: Structure

Although the system of rules in (36) is capable of describing the structures of a good number of English sentences, it is clear that we would need many more rules to attempt to describe the structures of all English sentences. For example, not every DP is made up of a determiner followed by a noun. Some may contain just a determiner, such as this for example, or a determiner, an adjective and a noun, such as a rusty kettle. A DP may indeed contain, amongst other things another sentence, such as the diagnosis that she had flu. It is clear that we would need many rewrite rules to capture all the possibilities for English DPs.

This fact does not invalidate this kind of rule for linguistic descriptive purposes. As long as there is only a finite number of rules, a legitimate grammar could be formulated even with a very large number of them. However, if human grammars are constructed of a large number of rules the question is raised of how children could ever learn their grammatical systems. This consideration has lead some linguists to assume that what is needed is a far more restricted set of rules. We will introduce the theory of phrase structure that follows this line of thought in the next chapter.

2 Grammatical Functions

2.1The subject

In all the sentences we have looked at so far, there has been an argument of the verb which appears to its left. All of the other arguments have appeared after the verb. As we see by the following sentences, this is an essential fact about grammatical English sentences:

(37)a Garry gave Victor a radio b *gave Garry Victor a radio c *Victor Gary gave a radio d *a radio Victor Gary gave

While there is a special way to pronounce these words in the order in (37c) that would make it grammatical (with a pause after Victor), this would have a special interpretation in which Victor is singled out from a set of possible referents and the rest of the sentence is taken to be something said particularly about him. However, without this special intonation and meaning the sentence is just as ungrammatical as the others: the ‘normal’ word order of English is as in (37a). Thus the basic word order of English has one and only one argument of the verb to its left and all the others to its right.

From a structural point of view, the argument that precedes the verb also differs from the other arguments. This argument is an immediate constituent of the sentence, whereas all other arguments are inside the verb phrase:

(38) |

S |

DP VP

Gary gave DP |

DP |

Victor a radio

Note:

A triangle is used in a tree diagram when we do not want to represent the details of the internal structure of the phrase.

68

Grammatical Functions

We call the argument that precedes the VP in the sentence the subject. Besides its privileged position in the sentence, the subject also plays an important role in a number of different phenomena. In a finite sentence, the verb may have a different form depending on properties of the subject:

(39)a I/you eat breakfast at 6.30 b we/they eat breakfast at 8

c he/she/Ernie eats breakfast at 9.15

When the subject refers to either the speaker or the addressee, what we call first and second person, the finite verb in present tense shows no overt morphology. The same is true when the subject is plural. However, when the subject is third person (referring neither to the speaker nor the addressee) and singular the present tense verb inflects with an ‘s’. This morpheme not only shows the tense therefore, but also the nature of the subject: that it is third person singular. This phenomenon is known as agreement: we say that the verb agrees with the subject.

Clearly English does not have much in the way of agreement morphology, usually distinguishing just the two cases given above, though the verb be has three agreement forms in the present tense and two in the past tense:

(40)a I am ready

b you/we/they are ready c he/she/Iggy is ready

d I/he/she/Wanda was ready e you/we/they were ready

Other languages, however, show a good deal more, as the following Hungarian examples show:

(41)a (én) 6-kor reggelizek b (te) 6-kor reggelizel c ( ) 6-kor reggelizik

d (mi) 6-kor reggelizünk e (ti) 6-kor reggeliztek

f ( k) 6-kor reggeliznek

(I eat breakfast at 6) (you eat breakfast at 6)

(he/she eats breakfast at 6) (we eat breakfast at 6) (you(plural) eat breakfast at 6) (they eat breakfast at 6)

Hungarian verbal morphology is a good deal more complex than this, though it is not my intention to go into it here. The point is that although English has less agreement morphology than Hungarian, the phenomenon is the same in that the form of the verb reflects person and number properties of the subject. In English, the other arguments have no effect on the form of the verb:

(42)TV bores me/you/him/…

Thus agreement is a relationship that holds between the subject and the finite verb. Another aspect of the subject that shows up in finite clauses concerns the form of

the subject itself. Previously we introduced the notion of Case, which is morphologically apparent only on pronouns in English. The subject of the finite clause is the only position where a nominative pronoun (I, he, she, we, they) can appear. In all

69

Chapter 2 - Grammatical Foundations: Structure

other positions English pronouns have the accusative form (me, him, her, us, them – you and it are the same in nominative and accusative):

(43)a I/he/she/we/they will consider the problem b Robert recognised me/him/her/us/them

c Lester never listens to me/him/her/us/them

d Conrad considers me/him/her/us/them to be dangerous

In (43a) the pronouns are the subject of the finite clause and are in their nominative forms, in (43b) they act as the complement of the verb (a position which we will return to), in (43c), complement of a preposition and in (43d) subject of a non-finite clause containing the infinitive marker to, and they are in their accusative forms.

A further grammatical fact about the subject of the finite clause is that it is always present. That this is a grammatical fact is most clearly shown by the fact that if there is no need for a subject semantically, a grammatical subject which has no meaning has to appear:

(44)it seems [that Roger ran away]

The verb seem has just one argument, the clause that Roger ran away, which acts as its complement. Thus from a semantic point of view there is no subject argument here. Yet there is a subject, the pronoun it, which in this case has no meaning. Note that this it is not the same as the one that refers to a third person non-human, as in the following:

(45)it bit me!

With (45) one could question the pronoun subject and expect to get an answer:

(46)Q: what bit you? – A: that newt!

With (44) however, this is not possible because the pronoun does not refer to anything:

(47) |

Q: what seems [that Roger ran away]? |

– A: ??? |

These meaningless subjects are often called expletive or pleonastic subjects, both terms meaning meaningless.

The appearance of an expletive element is restricted to the subject position. We do not get an expletive in a complement position of intransitive verbs, which do not subcategorise for a complement:

(48) a |

*Sam smiled it |

(Sam smiled) |

b |

*Sue sat it |

(Sue sat) |

The subject of non-finite clauses is a little more complex as there are occasions where they are necessary and hence an expletive must appear if there is no semantic subject, and there are other cases where the position must be left empty, even though there is semantic interpretation for it:

(49)a I consider [it to be obvious who the murderer is] b *I consider [- to be obvious who the murderer is]

(50)a Terry tried [- to escape]

b *Terry tried [himself to escape]

70