grammatical foundations

.pdf

The syntax of inflection

(53) a |

I quickly assessed the students |

– |

*I assessed quickly the students |

b |

I did not fail his paper |

– |

*I failed not his paper |

We already have an account for the behaviour of the main verb in the presence of the negative. The negative is a head that blocks the movement of the verb over it. If negation is situated below the I position, then the verb will not be able to move to support the inflection and hence do-support is necessary, as demonstrated in (53b). This will not affect the process of auxiliary insertion however, as this does not involve movement. Yet, an inserted auxiliary bears both tense and agreement and so it seems to be inserted into tense and moved to I, suggesting that the position of the negation is lower than the tensed element, contradicting (49b) where negation is above the nonfinite tense. It seems then that negation must be below a finite tense, but above the verb.

The only real problem we face is accounting for the grammaticality of (53a), where the adverb appears in front of the tensed verb. It is this observation which has lead people to the assumption that the inflection must lower to the verb or that the analysis must be more abstract to account for what looks like a downward movement in terms of an upward one.

However, these approaches are based on the assumption that the position of the adverb is rigidly fixed and so if the verb follows the adverb it must be inside the vP. But we have seen that adverbial placement is not so rigid, although it is subject to some restrictions. It would seem to me to be more straightforward to assume that in the case of a finite main verb, the verb does occupy the inflection position and what needs accounting for is the position of the adverb.

Suppose that, like the negative element, the adverb likes to follow the finite tense and precede the verb. However, unlike the negative it is not rigid about this. Specifically, when the verb and the inflection are in one place, it is impossible for the adverb to be between them. Thus a choice must be made: put the adverb above the tense, or put it below the verb. It seems that the restriction on adverbs preceding verbs is the stronger, so the adverb will be adjoined higher than the I position. The position it is actually adjoined to is the I©, which we will see is a position where the sentential adverb may appear:

(54) |

IP |

|

|

DP |

|

I© |

|

they |

AP |

|

I© |

|

fervently |

I |

vP |

|

|

|

||

believed1- |

v© |

|||

|

v |

VP |

||

|

t |

|

1 |

everything I said t1 |

|

||||

231

Chapter 6 - Inflectional Phrases

As we mentioned previously, the negative element is not so accommodating and it refuses to give up its place below the finite inflection and above the verb. Thus in this case the verb cannot support the inflection and the dummy auxiliary has to be inserted:

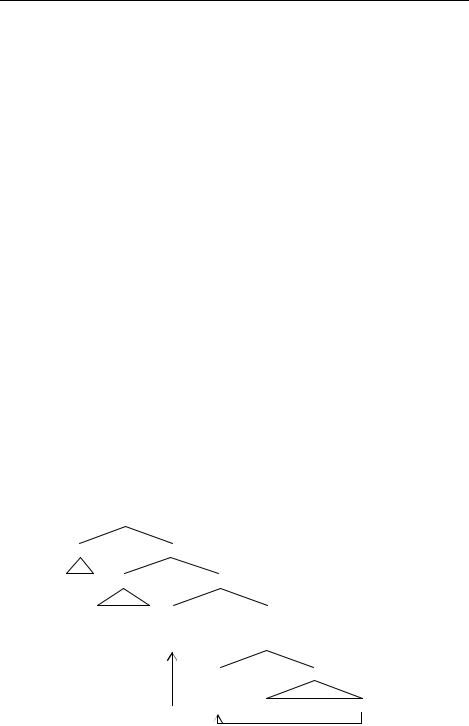

(55)IP

DP I©

he I |

vP |

- v©

v vP

do |

|

v© |

v VP

not borrow the book

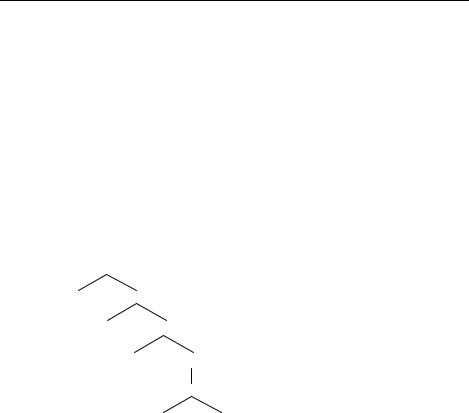

The final structure of the clause we end up with is as follows:

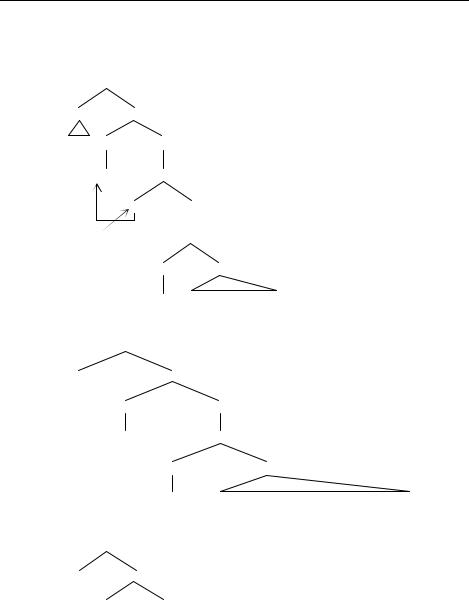

(56) |

IP |

– |

I© |

I |

vP |

mod/agr v©

v v/VP

tense |

(negation) (aspect) (light verbs) V |

In what follows, we may sometimes for convenience abbreviate this to:

(57)IP

–I©

I VP

However, the more articulated structure in (56) will be assumed to be correct and indeed will be essential for accounting for certain phenomena which will be introduced in the next chapter.

232

Movement to Spec IP

3 Movement to Spec IP

Up to this point we have been assuming that the subject of the clause originates fairly low in the clause, inside the VP or a vP just above it. We have said this DP will move from its original position to the specifier of IP to get Case and thus avoid a Case Filter violation which would render the sentence ungrammatical. Two aspects of this analysis are in need of elaboration. First it must be accounted for that the subject’s original position is a Caseless one and second it must be established exactly where in the complex clause structure we have been arguing for the subject moves to and why this is a Case position.

Let us start with the case of a simple transitive verb so that we can compare the situation of the subject and object:

(58)IP

–I©

I |

vP |

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

will |

v© |

|

|

||||

|

v |

|

vP |

|

|

||

|

|

|

DP |

v© |

|

||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Boris v |

|

VP |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

DP |

V© |

|

|

|

|

e |

|||

Ivan V

beat

We have said that the light verb which is responsible for assigning the -role to the subject is responsible for assigning Case to the object. This seems to be the locus of Burzio’s generalisation that verbs which assign a subject -role assign an accusative Case. Hence the object is in a Case marked position and need not move away in order to get Case. Consider the subject: why is it not in a Case position? Note that the verbal element above the subject, the tense in this case, does not assign any -roles and hence its specifier position is empty at D-structure. Clearly this is unlike the light verb. We may propose therefore that tense is not an accusative Case assigning head. But why doesn’t the light verb assign Case to its subject? One might attempt to answer this by claiming that the light verb has to assign Case to the object and assuming that accusative Case can only be assigned to one place. While this seems reasonable, it doesn’t explain why the light verb taking an intransitive verb does not assign Case to its subject:

233

Chapter 6 - Inflectional Phrases

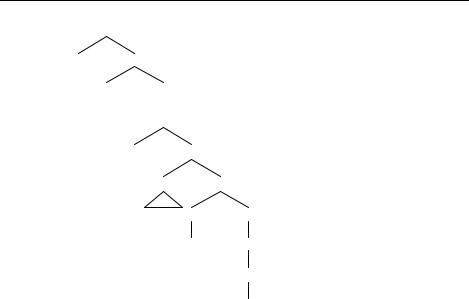

(59)IP

–I©

I |

vP |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

will |

v© |

|

|||

|

v |

|

vP |

|

|

|

|

|

DP |

v© |

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

Boris v |

VP |

|

eV© V

laugh

In this case, the light verb assigns agent -role to its specifier and so should be capable of assigning Case and in fact the possible appearance of a cognate object seems to confirm this assumption. But when there is no object, the subject still undergoes the movement, suggesting that it does not get Case from the light verb.

There are a number of possible ways to account for these observations. The simplest is to assume that Case assignment is directional and that accusative Case in English is assigned to the right. Thus, the light verb will be able to assign Case to the object as the object appears to the right. However the light verb will not be able to assign Case to the subject as the subject is in the specifier position and specifiers are to the left of the head.

This is too simple, however, as it is not the case that a light verb can assign Case to any element on its right. Consider a more complicated case in which we have a verb with a clausal complement. The light verb of this verb will be to the left of the complement clause and hence to the left of the subject of that clause. But it cannot assign accusative Case to this subject, allowing it to stay inside its own subject position:

234

Movement to Spec IP

(60) |

vP |

DP |

v© |

|

|

|

||

they v |

|

|

VP |

|

|

|

|

|

IP |

|

V© |

||

e |

|

|||||

|

|

– |

I© |

|

|

|

|

|

V |

||||

|

|

I |

vP |

|

|

|

|

|

think |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

will |

Larry leave |

|

|

|

(61)a *they think1-e [VP [IP - will Larry leave] t1] b they think1-e [VP [IP Larry2 will t2 leave] t1]

The word order within the embedded clause shows that the subject does not get Case in its original position and that like any other subject, it has to move to get Case in the subject position of the IP. Considering where a light verb can assign Case to, i.e. the specifier of its own VP complement, and where it cannot assign Case to, i.e. the specifier of a VP inside another clause, it is obvious that there is some locality restriction on Case assignment in addition to the directional one. We are not yet in a position to be able to determine the exact nature of this locality condition and so for now we will just assume that a light verb can only Case mark elements within its own clause.

Having put this in place, we can see that the subject will not be able to be case marked in its original position as it is on the wrong side of the local light verb and too far from any other light verb that might have a Case to assign.

Let us now turn to the landing site of the movement. The subject moves to a position to the left of a modal and so the obvious place to assume as its landing site is the specifier of IP:

(62)IP

DP1 I©

I vP

will t1

This must be a Case position as the sentence is grammatical with the subject sitting in it and therefore the Case Filter must be satisfied. If we assume that it is the inflection which is responsible for assigning the Case we account for why this is the landing site for this movement. Moreover, we also account for the difference between the subjects of finite and infinite clauses. Recall that while the subject of the finite clause has nominative Case, the typical Case for the subject of the non-finite clause is accusative:

235

Chapter 6 - Inflectional Phrases

(63)a she can sing

b for him to dance

Presumably the agreement element is different in both these cases. For one thing, modal auxiliaries can appear in the agreement position of finite clauses, but not of nonfinite clauses. Moreover, finite inflection selects for a finite tense headed phrase as its complement while the one in (63b) clearly selects for a non-finite complement. I will not have anything to say about the accusative Case of the subject of the non-finite clause at present, leaving this for future discussion. Instead, we will concentrate on the finite inflection, which assigns nominative to the subject.

The Case assigned by the finite agreement element is very different from that assigned to the object. Obviously the former is a nominative Case while the latter is accusative, but the differences extend further than this. For one thing assuming that it is the agreement element which is responsible for nominative Case, this Case must be assigned in a leftward direction:

(64)IP

DP I©

nominative I vP

will

Furthermore, this case is assigned by a functional element, something that is not involved in -role assignment. For accusative Case the Case assigner necessarily - marks its subject in order to be able to assign accusative Case. But the same is not true for the inflectional assigner of nominative Case.

There are two basic positions linguists take with respect to these observations. One is to assume that nominative and accusative Case are similar and the other assumes that they are fundamentally different. From the first perspective the challenge is to come up with restrictions which define the conditions under which Case can be assigned generally. For example, there are three positions to which we have seen a Case assigned: the specifier of the inflection; the specifier of the complement, and the complement position itself:

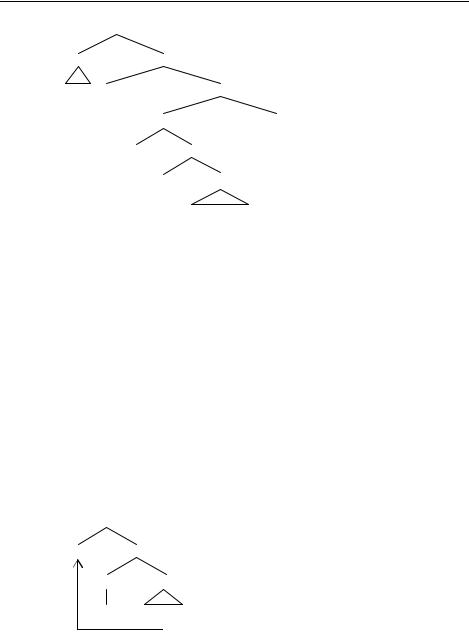

(65) |

IP |

|

vP |

|

|

PP |

|

|

DP |

I© |

v© |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

P© |

||||

|

I |

vP |

v |

VP |

P |

|

DP |

|

|

|

|

DP |

V© |

|

|

The unified relationship that linguists came up with to capture these three cases of Case assignment was called government. Informally this may be stated as:

236

Movement to Spec IP

(66)an element governs everything within its own phrase, but not past a certain point

The point of the ‘but’ clause in this definition is to impose locality on government. If a head governs everything inside its phrase, then it can govern quite a long way if its phrase happens to be a long one. Yet government is clearly a local relationship if it is restricted to the situations in (65) and there seems to be a point beyond which government cannot hold. How this point is identified and defined is a matter for discussion, with a number of positions possible. But one thing we can conclude at this point is that VP cannot be something that blocks government, otherwise the light verb would not be able to Case-mark the object in the specifier of VP.

The other point of view observes that it does not seem to be mere coincidence that the two instances of rightward Case assignment in (65) happen to involve accusative Case while the leftward Case assignment involves nominative. The assumption is then that there are two different processes at work here. For nominative the relevant relationship is supposed to be specifier–head agreement, something we mentioned in the previous chapter. The idea is that the finite inflectional element can assign nominative Case to whatever it agrees with, and this will be its specifier. For accusative Case however, government is the relevant relationship, though defined in a slightly different way as it is no longer required to extend to the subject. Informally, this version of government can be defined as:

(67)a head governs its sister and everything inside its sister, up to a point.

Again, the ‘point’ imposes locality restrictions on the government relationships. From the present perspective there is very little between the two views that allow us to favour one or the other and therefore we will leave the matter unresolved at this point.

237

Chapter 6 - Inflectional Phrases

4 Adjunction within IP

In the last section of this chapter we will briefly consider adjunction within the clause. We have seen in the last chapter that adverbs come in at least two types: sentential adverbs and VP adverbs. The two can be distinguished by what they modify and also in terms of where they attach to a structure.

Sentential modifiers are normally considered to have the whole sentence as their domain of modification, i.e. they add an extra meaning to the sentence as a whole:

(68)a she will certainly be offended b it will probably never happen c I had luckily saved the envelope

Note that the most natural position for these adverbs is after the modal but before the rest of the sentence, suggesting that it adjoins to the phrase headed by tense:

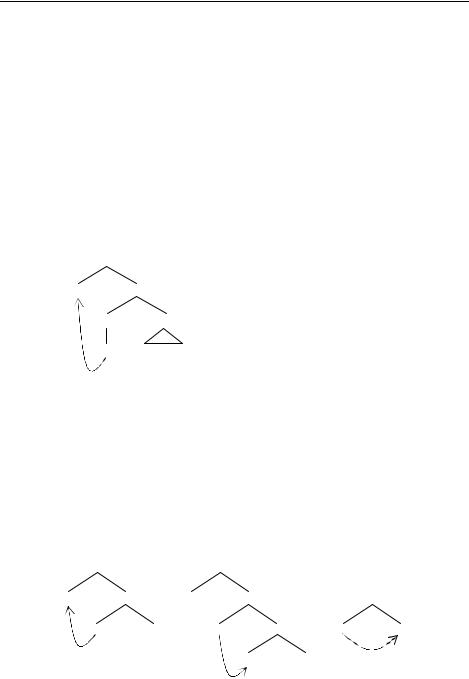

(69)IP

DP I©

I vP

AP vP

v©

v vP

We do however find them following the subject but before the inflection:

(70)a he naturally could cook

b they hopefully might know the way

c I regrettably have forgotten your name

The only place that an adverb would be able to attach to, to come between a head and its specifier, is the X©.So unless we assume either that subjects are not necessarily in the specifier of the inflection or that the modals are not necessarily in the inflection position itself, it seems that we must also allow adjuncts to adjoin to the I©:

238

Conclusion

(71)IP

DP I©

AP I©

IvP v©

v vP

Note that both of these positions are higher than those favoured by the VP adverbs and hence if we have a sentential adverb and a VP adverb, we predict that the sentential adverb will precede, which seems to hold true:

(72)a I can fortunately quickly send you the money b *I can quickly fortunately send you the money

5 Conclusion

In this chapter we have discussed the basic architecture of the clause, claiming that this is headed by the inflectional element. This analysis provides positions for both the subject and the VP as well as the inflectional element itself. However, there are aspects of the syntax of the clause that we have not yet touched upon. We have yet to discuss the position of the complementiser, for example. Furthermore, there are types of clauses that we have not discussed: interrogatives, for example. These will be discussed in the next chapters.

Check Questions

1How can finite and non-finite clauses be distinguished?

2What evidence is available to assume that clauses are not exocentric constructions, rather, they are headed by the element I?

3How is the process of attaching bound morpheme inflection heads to their stems analysed?

4What is the analysis of negation and do-support?

5What is the position associated with aspect markers and aspectual auxiliaries?

6How is the conceptualisation of the content of Inflection altered in the text?

7What is the distribution of negation and VP adverbs relative to each other?

8What is the difference between light verb vP and tense vP?

9How is Case assignment conceptualised?

10What is the position of sentence adverbs versus VP adverbs?

239

Chapter 6 - Inflectional Phrases

Test your knowledge

Exercise 1

Consider the examples below. How do the DPs acquire case?

(1)a John met Mary in the park.

bFor me to survive this week will be quite difficult.

cEverybody goes to see the painting.

dJohn persuaded Bill to go to see a doctor.

eMary gave a book to John for Xmas.

Exercise 2

Determine the function of do in the following sentences.

(1)a How do you do?

bHe did know the answer although he claimed he did not know it.

cShe does a lot for her parents.

dHe did not tell the truth, did he?

eWhen does he get up?

fI did read this book.

gThey do not go to work today.

hYou sleep too much, don’t you?

iI have quite a lot of things to do.

jThis exercise is almost done now.

kWhat are you doing now?

lI do not know anything.

Exercise 3

Identify the DPs in the following sentences and state which Case is assigned to them by which items.

(1)a Jim sent a bunch of flowers to Jane.

bFor Jim not to buy the house at a lower price wasn’t the best decision in his life.

cThe teacher believed that all his students would pass the exam.

dAll the students were believed to pass the exam.

eJohn will never trust Jane.

fWhich experiment did the professor mean when he asked whether we were able to do it?

gJohn read an interesting book about the cold war.

hIt was raining when I looked out of the window.

iThe children wanted it to be snowing during the whole day.

jJane believed Jack to be able to repair the car.

240