- •Preface

- •Approach and Pedagogy

- •Chapter 1

- •Introducing Psychology

- •1.1 Psychology as a Science

- •The Problem of Intuition

- •Research Focus: Unconscious Preferences for the Letters of Our Own Name

- •Why Psychologists Rely on Empirical Methods

- •Levels of Explanation in Psychology

- •The Challenges of Studying Psychology

- •1.2 The Evolution of Psychology: History, Approaches, and Questions

- •Early Psychologists

- •Structuralism: Introspection and the Awareness of Subjective Experience

- •Functionalism and Evolutionary Psychology

- •Psychodynamic Psychology

- •Behaviorism and the Question of Free Will

- •Research Focus: Do We Have Free Will?

- •The Cognitive Approach and Cognitive Neuroscience

- •The War of the Ghosts

- •Social-Cultural Psychology

- •The Many Disciplines of Psychology

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: How to Effectively Learn and Remember

- •1.3 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 2

- •Psychological Science

- •Psychological Journals

- •2.1 Psychologists Use the Scientific Method to Guide Their Research

- •The Scientific Method

- •Laws and Theories as Organizing Principles

- •The Research Hypothesis

- •Conducting Ethical Research

- •Characteristics of an Ethical Research Project Using Human Participants

- •Ensuring That Research Is Ethical

- •Research With Animals

- •APA Guidelines on Humane Care and Use of Animals in Research

- •Descriptive Research: Assessing the Current State of Affairs

- •Correlational Research: Seeking Relationships Among Variables

- •Experimental Research: Understanding the Causes of Behavior

- •Research Focus: Video Games and Aggression

- •2.3 You Can Be an Informed Consumer of Psychological Research

- •Threats to the Validity of Research

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Critically Evaluating the Validity of Websites

- •2.4 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 3

- •Brains, Bodies, and Behavior

- •Did a Neurological Disorder Cause a Musician to Compose Boléro and an Artist to Paint It 66 Years Later?

- •3.1 The Neuron Is the Building Block of the Nervous System

- •Neurons Communicate Using Electricity and Chemicals

- •Video Clip: The Electrochemical Action of the Neuron

- •Neurotransmitters: The Body’s Chemical Messengers

- •3.2 Our Brains Control Our Thoughts, Feelings, and Behavior

- •The Old Brain: Wired for Survival

- •The Cerebral Cortex Creates Consciousness and Thinking

- •Functions of the Cortex

- •The Brain Is Flexible: Neuroplasticity

- •Research Focus: Identifying the Unique Functions of the Left and Right Hemispheres Using Split-Brain Patients

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Why Are Some People Left-Handed?

- •3.3 Psychologists Study the Brain Using Many Different Methods

- •Lesions Provide a Picture of What Is Missing

- •Recording Electrical Activity in the Brain

- •Peeking Inside the Brain: Neuroimaging

- •Research Focus: Cyberostracism

- •3.4 Putting It All Together: The Nervous System and the Endocrine System

- •Electrical Control of Behavior: The Nervous System

- •The Body’s Chemicals Help Control Behavior: The Endocrine System

- •3.5 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 4

- •Sensing and Perceiving

- •Misperception by Those Trained to Accurately Perceive a Threat

- •4.1 We Experience Our World Through Sensation

- •Sensory Thresholds: What Can We Experience?

- •Link

- •Measuring Sensation

- •Research Focus: Influence without Awareness

- •4.2 Seeing

- •The Sensing Eye and the Perceiving Visual Cortex

- •Perceiving Color

- •Perceiving Form

- •Perceiving Depth

- •Perceiving Motion

- •Beta Effect and Phi Phenomenon

- •4.3 Hearing

- •Hearing Loss

- •4.4 Tasting, Smelling, and Touching

- •Tasting

- •Smelling

- •Touching

- •Experiencing Pain

- •4.5 Accuracy and Inaccuracy in Perception

- •How the Perceptual System Interprets the Environment

- •Video Clip: The McGurk Effect

- •Video Clip: Selective Attention

- •Illusions

- •The Important Role of Expectations in Perception

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: How Understanding Sensation and Perception Can Save Lives

- •4.6 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 5

- •States of Consciousness

- •An Unconscious Killing

- •5.1 Sleeping and Dreaming Revitalize Us for Action

- •Research Focus: Circadian Rhythms Influence the Use of Stereotypes in Social Judgments

- •Sleep Stages: Moving Through the Night

- •Sleep Disorders: Problems in Sleeping

- •The Heavy Costs of Not Sleeping

- •Dreams and Dreaming

- •5.2 Altering Consciousness With Psychoactive Drugs

- •Speeding Up the Brain With Stimulants: Caffeine, Nicotine, Cocaine, and Amphetamines

- •Slowing Down the Brain With Depressants: Alcohol, Barbiturates and Benzodiazepines, and Toxic Inhalants

- •Opioids: Opium, Morphine, Heroin, and Codeine

- •Hallucinogens: Cannabis, Mescaline, and LSD

- •Why We Use Psychoactive Drugs

- •Research Focus: Risk Tolerance Predicts Cigarette Use

- •5.3 Altering Consciousness Without Drugs

- •Changing Behavior Through Suggestion: The Power of Hypnosis

- •Reducing Sensation to Alter Consciousness: Sensory Deprivation

- •Meditation

- •Video Clip: Try Meditation

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: The Need to Escape Everyday Consciousness

- •5.4 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 6

- •Growing and Developing

- •The Repository for Germinal Choice

- •6.1 Conception and Prenatal Development

- •The Zygote

- •The Embryo

- •The Fetus

- •How the Environment Can Affect the Vulnerable Fetus

- •6.2 Infancy and Childhood: Exploring and Learning

- •The Newborn Arrives With Many Behaviors Intact

- •Research Focus: Using the Habituation Technique to Study What Infants Know

- •Cognitive Development During Childhood

- •Video Clip: Object Permanence

- •Social Development During Childhood

- •Knowing the Self: The Development of the Self-Concept

- •Video Clip: The Harlows’ Monkeys

- •Video Clip: The Strange Situation

- •Research Focus: Using a Longitudinal Research Design to Assess the Stability of Attachment

- •6.3 Adolescence: Developing Independence and Identity

- •Physical Changes in Adolescence

- •Cognitive Development in Adolescence

- •Social Development in Adolescence

- •Developing Moral Reasoning: Kohlberg’s Theory

- •Video Clip: People Being Interviewed About Kohlberg’s Stages

- •6.4 Early and Middle Adulthood: Building Effective Lives

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: What Makes a Good Parent?

- •Physical and Cognitive Changes in Early and Middle Adulthood

- •Menopause

- •Social Changes in Early and Middle Adulthood

- •6.5 Late Adulthood: Aging, Retiring, and Bereavement

- •Cognitive Changes During Aging

- •Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease

- •Social Changes During Aging: Retiring Effectively

- •Death, Dying, and Bereavement

- •6.6 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 7

- •Learning

- •My Story of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- •7.1 Learning by Association: Classical Conditioning

- •Pavlov Demonstrates Conditioning in Dogs

- •The Persistence and Extinction of Conditioning

- •The Role of Nature in Classical Conditioning

- •How Reinforcement and Punishment Influence Behavior: The Research of Thorndike and Skinner

- •Video Clip: Thorndike’s Puzzle Box

- •Creating Complex Behaviors Through Operant Conditioning

- •7.3 Learning by Insight and Observation

- •Observational Learning: Learning by Watching

- •Video Clip: Bandura Discussing Clips From His Modeling Studies

- •Research Focus: The Effects of Violent Video Games on Aggression

- •7.4 Using the Principles of Learning to Understand Everyday Behavior

- •Using Classical Conditioning in Advertising

- •Video Clip: Television Ads

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Operant Conditioning in the Classroom

- •Reinforcement in Social Dilemmas

- •7.5 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 8

- •Remembering and Judging

- •She Was Certain, but She Was Wrong

- •Differences between Brains and Computers

- •Video Clip: Kim Peek

- •8.1 Memories as Types and Stages

- •Explicit Memory

- •Implicit Memory

- •Research Focus: Priming Outside Awareness Influences Behavior

- •Stages of Memory: Sensory, Short-Term, and Long-Term Memory

- •Sensory Memory

- •Short-Term Memory

- •8.2 How We Remember: Cues to Improving Memory

- •Encoding and Storage: How Our Perceptions Become Memories

- •Research Focus: Elaboration and Memory

- •Using the Contributions of Hermann Ebbinghaus to Improve Your Memory

- •Retrieval

- •Retrieval Demonstration

- •States and Capital Cities

- •The Structure of LTM: Categories, Prototypes, and Schemas

- •The Biology of Memory

- •8.3 Accuracy and Inaccuracy in Memory and Cognition

- •Source Monitoring: Did It Really Happen?

- •Schematic Processing: Distortions Based on Expectations

- •Misinformation Effects: How Information That Comes Later Can Distort Memory

- •Overconfidence

- •Heuristic Processing: Availability and Representativeness

- •Salience and Cognitive Accessibility

- •Counterfactual Thinking

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Cognitive Biases in the Real World

- •8.4 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 9

- •Intelligence and Language

- •How We Talk (or Do Not Talk) about Intelligence

- •9.1 Defining and Measuring Intelligence

- •General (g) Versus Specific (s) Intelligences

- •Measuring Intelligence: Standardization and the Intelligence Quotient

- •The Biology of Intelligence

- •Is Intelligence Nature or Nurture?

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Emotional Intelligence

- •9.2 The Social, Cultural, and Political Aspects of Intelligence

- •Extremes of Intelligence: Retardation and Giftedness

- •Extremely Low Intelligence

- •Extremely High Intelligence

- •Sex Differences in Intelligence

- •Racial Differences in Intelligence

- •Research Focus: Stereotype Threat

- •9.3 Communicating With Others: The Development and Use of Language

- •The Components of Language

- •Examples in Which Syntax Is Correct but the Interpretation Can Be Ambiguous

- •The Biology and Development of Language

- •Research Focus: When Can We Best Learn Language? Testing the Critical Period Hypothesis

- •Learning Language

- •How Children Learn Language: Theories of Language Acquisition

- •Bilingualism and Cognitive Development

- •Can Animals Learn Language?

- •Video Clip: Language Recognition in Bonobos

- •Language and Perception

- •9.4 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 10

- •Emotions and Motivations

- •Captain Sullenberger Conquers His Emotions

- •10.1 The Experience of Emotion

- •Video Clip: The Basic Emotions

- •The Cannon-Bard and James-Lange Theories of Emotion

- •Research Focus: Misattributing Arousal

- •Communicating Emotion

- •10.2 Stress: The Unseen Killer

- •The Negative Effects of Stress

- •Stressors in Our Everyday Lives

- •Responses to Stress

- •Managing Stress

- •Emotion Regulation

- •Research Focus: Emotion Regulation Takes Effort

- •10.3 Positive Emotions: The Power of Happiness

- •Finding Happiness Through Our Connections With Others

- •What Makes Us Happy?

- •10.4 Two Fundamental Human Motivations: Eating and Mating

- •Eating: Healthy Choices Make Healthy Lives

- •Obesity

- •Sex: The Most Important Human Behavior

- •The Experience of Sex

- •The Many Varieties of Sexual Behavior

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Regulating Emotions to Improve Our Health

- •10.5 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 11

- •Personality

- •Identical Twins Reunited after 35 Years

- •11.1 Personality and Behavior: Approaches and Measurement

- •Personality as Traits

- •Example of a Trait Measure

- •Situational Influences on Personality

- •The MMPI and Projective Tests

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Leaders and Leadership

- •11.2 The Origins of Personality

- •Psychodynamic Theories of Personality: The Role of the Unconscious

- •Id, Ego, and Superego

- •Research Focus: How the Fear of Death Causes Aggressive Behavior

- •Strengths and Limitations of Freudian and Neo-Freudian Approaches

- •Focusing on the Self: Humanism and Self-Actualization

- •Research Focus: Self-Discrepancies, Anxiety, and Depression

- •Studying Personality Using Behavioral Genetics

- •Studying Personality Using Molecular Genetics

- •Reviewing the Literature: Is Our Genetics Our Destiny?

- •11.4 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 12

- •Defining Psychological Disorders

- •When Minor Body Imperfections Lead to Suicide

- •12.1 Psychological Disorder: What Makes a Behavior “Abnormal”?

- •Defining Disorder

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Combating the Stigma of Abnormal Behavior

- •Diagnosing Disorder: The DSM

- •Diagnosis or Overdiagnosis? ADHD, Autistic Disorder, and Asperger’s Disorder

- •Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- •Autistic Disorder and Asperger’s Disorder

- •12.2 Anxiety and Dissociative Disorders: Fearing the World Around Us

- •Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- •Panic Disorder

- •Phobias

- •Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders

- •Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- •Dissociative Disorders: Losing the Self to Avoid Anxiety

- •Dissociative Amnesia and Fugue

- •Dissociative Identity Disorder

- •Explaining Anxiety and Dissociation Disorders

- •12.3 Mood Disorders: Emotions as Illness

- •Behaviors Associated with Depression

- •Dysthymia and Major Depressive Disorder

- •Bipolar Disorder

- •Explaining Mood Disorders

- •Research Focus: Using Molecular Genetics to Unravel the Causes of Depression

- •12.4 Schizophrenia: The Edge of Reality and Consciousness

- •Symptoms of Schizophrenia

- •Explaining Schizophrenia

- •12.5 Personality Disorders

- •Borderline Personality Disorder

- •Research Focus: Affective and Cognitive Deficits in BPD

- •Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD)

- •12.6 Somatoform, Factitious, and Sexual Disorders

- •Somatoform and Factitious Disorders

- •Sexual Disorders

- •Disorders of Sexual Function

- •Paraphilias

- •12.7 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 13

- •Treating Psychological Disorders

- •Therapy on Four Legs

- •13.1 Reducing Disorder by Confronting It: Psychotherapy

- •DSM-IV-TR Criteria for Diagnosing Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Seeking Treatment for Psychological Difficulties

- •Psychodynamic Therapy

- •Important Characteristics and Experiences in Psychoanalysis

- •Humanistic Therapies

- •Behavioral Aspects of CBT

- •Cognitive Aspects of CBT

- •Combination (Eclectic) Approaches to Therapy

- •13.2 Reducing Disorder Biologically: Drug and Brain Therapy

- •Drug Therapies

- •Using Stimulants to Treat ADHD

- •Antidepressant Medications

- •Antianxiety Medications

- •Antipsychotic Medications

- •Direct Brain Intervention Therapies

- •13.3 Reducing Disorder by Changing the Social Situation

- •Group, Couples, and Family Therapy

- •Self-Help Groups

- •Community Mental Health: Service and Prevention

- •Some Risk Factors for Psychological Disorders

- •Research Focus: The Implicit Association Test as a Behavioral Marker for Suicide

- •13.4 Evaluating Treatment and Prevention: What Works?

- •Effectiveness of Psychological Therapy

- •Research Focus: Meta-Analyzing Clinical Outcomes

- •Effectiveness of Biomedical Therapies

- •Effectiveness of Social-Community Approaches

- •13.5 Chapter Summary

- •Chapter 14

- •Psychology in Our Social Lives

- •Binge Drinking and the Death of a Homecoming Queen

- •14.1 Social Cognition: Making Sense of Ourselvesand Others

- •Perceiving Others

- •Forming Judgments on the Basis of Appearance: Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination

- •Implicit Association Test

- •Research Focus: Forming Judgments of People in Seconds

- •Close Relationships

- •Causal Attribution: Forming Judgments by Observing Behavior

- •Attitudes and Behavior

- •14.2 Interacting With Others: Helping, Hurting, and Conforming

- •Helping Others: Altruism Helps Create Harmonious Relationships

- •Why Are We Altruistic?

- •How the Presence of Others Can Reduce Helping

- •Video Clip: The Case of Kitty Genovese

- •Human Aggression: An Adaptive yet Potentially Damaging Behavior

- •The Ability to Aggress Is Part of Human Nature

- •Negative Experiences Increase Aggression

- •Viewing Violent Media Increases Aggression

- •Video Clip

- •Research Focus: The Culture of Honor

- •Conformity and Obedience: How Social Influence Creates Social Norms

- •Video Clip

- •Do We Always Conform?

- •14.3 Working With Others: The Costs and Benefits of Social Groups

- •Working in Front of Others: Social Facilitation and Social Inhibition

- •Working Together in Groups

- •Psychology in Everyday Life: Do Juries Make Good Decisions?

- •Using Groups Effectively

- •14.4 Chapter Summary

Karen Wynn found that babies that had habituated to a puppet jumping either two or three times significantly increased their gaze when the puppet began to jump a different number of times.

Source: Adapted from Wynn, K. (1995). Infants possess a system of numerical knowledge. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4, 172–176.

Cognitive Development During Childhood

Childhood is a time in which changes occur quickly. The child is growing physically, and cognitive abilities are also developing. During this time the child learns to actively manipulate and control the environment, and is first exposed to the requirements of society, particularly the need to control the bladder and bowels. According to Erik Erikson, the challenges that the child must attain in childhood relate to the development of initiative, competence, and independence. Children need to learn to explore the world, to become self-reliant, and to make their own way in the environment.

These skills do not come overnight. Neurological changes during childhood provide children the ability to do some things at certain ages, and yet make it impossible for them to do other things. This fact was made apparent through the groundbreaking work of the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget. During the 1920s, Piaget was administering intelligence tests to children in an attempt to determine the kinds of logical thinking that children were capable of. In the process of testing the children, Piaget became intrigued, not so much by the answers that the children got right, but more by the answers they got wrong. Piaget believed that the incorrect answers that the children gave were not mere shots in the dark but rather represented specific ways of thinking unique to the children’s developmental stage. Just as almost all babies learn to roll over before they learn to sit up by themselves, and learn to crawl before they learn to walk, Piaget believed that children gain their cognitive ability in a developmental order. These insights—that children at different ages think in fundamentally different ways—led to Piaget’s stage model of cognitive development.

Piaget argued that children do not just passively learn but also actively try to make sense of their worlds. He argued that, as they learn and mature, children develop schemas—patterns of knowledge in long-term memory—that help them remember, organize, and respond to information. Furthermore, Piaget thought that when children experience new things, they attempt

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

268 |

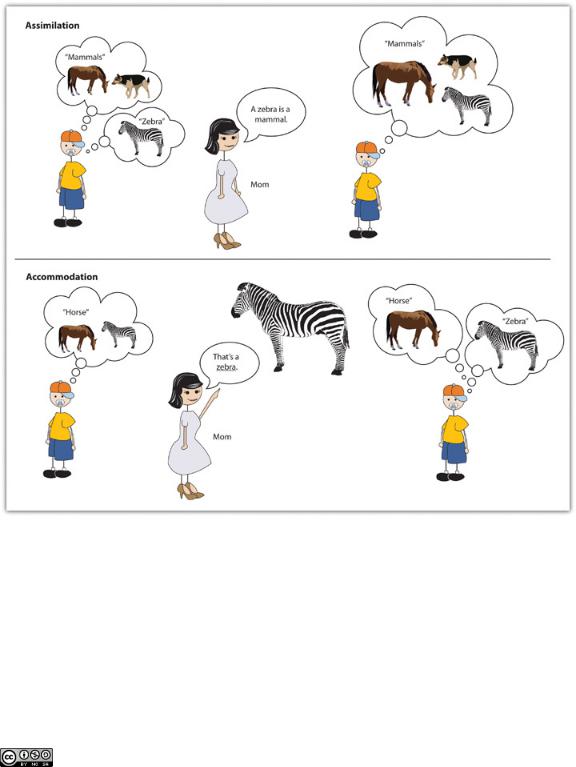

to reconcile the new knowledge with existing schemas. Piaget believed that the children use two distinct methods in doing so, methods that he called assimilation andaccommodation (see Figure 6.5 "Assimilation and Accommodation").

Figure 6.5 Assimilation and Accommodation

When children employ assimilation, they use already developed schemas to understand new information. If children have learned a schema for horses, then they may call the striped animal they see at the zoo a horse rather than a zebra. In this case, children fit the existing schema to the new information and label the new information with the existing knowledge. Accommodation, on the other hand, involves learning new information, and thus changing the schema. When a mother says, “No, honey, that’s a zebra, not a horse,” the child may adapt the schema to fit the

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

269 |

new stimulus, learning that there are different types of four-legged animals, only one of which is a horse.

Piaget’s most important contribution to understanding cognitive development, and the fundamental aspect of his theory, was the idea that development occurs in unique and distinct stages, with each stage occurring at a specific time, in a sequential manner, and in a way that allows the child to think about the world using new capacities. Piaget’s stages of cognitive development are summarized in Table 6.3 "Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development".

Table 6.3 Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

Approximate

Stage |

age range |

Characteristics |

Stage attainments |

|

|

|

|

|

Birth to about 2 The child experiences the world through the fundamental |

|

|

Sensorimotor |

years |

senses of seeing, hearing, touching, and tasting. |

Object permanence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Children acquire the ability to internally represent the |

Theory of mind; rapid |

|

|

world through language and mental imagery. They also |

increase in language |

Preoperational |

2 to 7 years |

start to see the world from other people’s perspectives. |

ability |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Children become able to think logically. They can |

|

Concrete |

|

increasingly perform operations on objects that are only |

|

operational |

7 to 11 years |

imagined. |

Conservation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adolescents can think systematically, can reason about |

|

Formal |

11 years to |

abstract concepts, and can understand ethics and scientific |

|

operational |

adulthood |

reasoning. |

Abstract logic |

The first developmental stage for Piaget was the sensorimotor stage, the cognitive stage that begins at birth and lasts until around the age of 2. It is defined by the direct physical interactions that babies have with the objects around them. During this stage, babies form their first schemas by using their primary senses—they stare at, listen to, reach for, hold, shake, and taste the things in their environments.

During the sensorimotor stage, babies’ use of their senses to perceive the world is so central to their understanding that whenever babies do not directly perceive objects, as far as they are concerned, the objects do not exist. Piaget found, for instance, that if he first interested babies in

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

270 |

a toy and then covered the toy with a blanket, children who were younger than 6 months of age would act as if the toy had disappeared completely—they never tried to find it under the blanket but would nevertheless smile and reach for it when the blanket was removed. Piaget found that it was not until about 8 months that the children realized that the object was merely covered and not gone. Piaget used the term object permanence to refer to the child’s ability to know that an object exists even when the object cannot be perceived.

Video Clip: Object Permanence

Children younger than about 8 months of age do not understand object permanence.

At about 2 years of age, and until about 7 years of age, children move into thepreoperational stage. During this stage, children begin to use language and to think more

abstractly about objects, but their understanding is more intuitive and without much ability to deduce or reason. The thinking is preoperational, meaning that the child lacks the ability to operate on or transform objects mentally. In one study that showed the extent of this inability, Judy DeLoache (1987) [10] showed children a room within a small dollhouse. Inside the room, a small toy was visible behind a small couch. The researchers took the children to another lab room, which was an exact replica of the dollhouse room, but full-sized. When children who were 2.5 years old were asked to find the toy, they did not know where to look—they were simply unable to make the transition across the changes in room size. Three-year-old children, on the other hand, immediately looked for the toy behind the couch, demonstrating that they were improving their operational skills.

The inability of young children to view transitions also leads them to beegocentric—unable to readily see and understand other people’s viewpoints. Developmental psychologists define the theory of mind as the ability to take another person’s viewpoint, and the ability to do so increases rapidly during the preoperational stage. In one demonstration of the development of

theory of mind, a researcher shows a child a video of another child (let’s call her Anna) putting a ball in a red box. Then Anna leaves the room, and the video shows that while she is gone, a researcher moves the ball from the red box into a blue box. As the video continues, Anna comes back into the room. The child is then asked to point to the box where Anna will probably look to

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

271 |

find her ball. Children who are younger than 4 years of age typically are unable to understand that Anna does not know that the ball has been moved, and they predict that she will look for it in the blue box. After 4 years of age, however, children have developed a theory of mind—they realize that different people can have different viewpoints, and that (although she will be wrong) Anna will nevertheless think that the ball is still in the red box.

After about 7 years of age, the child moves into the concrete operational stage, which is marked by more frequent and more accurate use of transitions, operations, and abstract concepts, including those of time, space, and numbers. An important milestone during the concrete operational stage is the development of conservation—the understanding that changes in the form of an object do not necessarily mean changes in the quantity of the object. Children younger than 7 years generally think that a glass of milk that is tall holds more milk than a glass of milk that is shorter and wider, and they continue to believe this even when they see the same milk poured back and forth between the glasses. It appears that these children focus only on one dimension (in this case, the height of the glass) and ignore the other dimension (width). However, when children reach the concrete operational stage, their abilities to understand such transformations make them aware that, although the milk looks different in the different glasses, the amount must be the same.

Video Clip: Conservation

Children younger than about 7 years of age do not understand the principles of conservation.

At about 11 years of age, children enter the formal operational stage, which is marked by the ability to think in abstract terms and to use scientific and philosophical lines of thought. Children in the formal operational stage are better able to systematically test alternative ideas to determine their influences on outcomes. For instance, rather than haphazardly changing different aspects of a situation that allows no clear conclusions to be drawn, they systematically make changes in one thing at a time and observe what difference that particular change makes. They learn to use deductive reasoning, such as “if this, then that,” and they become capable of imagining situations that “might be,” rather than just those that actually exist.

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

272 |

Piaget’s theories have made a substantial and lasting contribution to developmental psychology. His contributions include the idea that children are not merely passive receptacles of information but rather actively engage in acquiring new knowledge and making sense of the world around them. This general idea has generated many other theories of cognitive development, each designed to help us better understand the development of the child’s information-processing skills (Klahr & McWinney, 1998; Shrager & Siegler, 1998). [11] Furthermore, the extensive research that Piaget’s theory has stimulated has generally supported his beliefs about the order in which cognition develops. Piaget’s work has also been applied in many domains—for instance, many teachers make use of Piaget’s stages to develop educational approaches aimed at the level children are developmentally prepared for (Driscoll, 1994; Levin, Siegler, & Druyan, 1990). [12]

Over the years, Piagetian ideas have been refined. For instance, it is now believed that object permanence develops gradually, rather than more immediately, as a true stage model would predict, and that it can sometimes develop much earlier than Piaget expected. Renée Baillargeon and her colleagues (Baillargeon, 2004; Wang, Baillargeon, & Brueckner, 2004) [13]placed babies in a habituation setup, having them watch as an object was placed behind a screen, entirely hidden from view. The researchers then arranged for the object to reappear from behind another screen in a different place. Babies who saw this pattern of events looked longer at the display than did babies who witnessed the same object physically being moved between the screens. These data suggest that the babies were aware that the object still existed even though it was hidden behind the screen, and thus that they were displaying object permanence as early as 3 months of age, rather than the 8 months that Piaget predicted.

Another factor that might have surprised Piaget is the extent to which a child’s social surroundings influence learning. In some cases, children progress to new ways of thinking and retreat to old ones depending on the type of task they are performing, the circumstances they find themselves in, and the nature of the language used to instruct them (Courage & Howe,

2002). [14] And children in different cultures show somewhat different patterns of cognitive

development. Dasen (1972) [15] found that children in non-Western cultures moved to the next developmental stage about a year later than did children from Western cultures, and that level of schooling also influenced cognitive development. In short, Piaget’s theory probably understated the contribution of environmental factors to social development.

Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/books |

Saylor.org |

|

273 |