Mugglestone - The Oxford History of English

.pdf188 terttu nevalainen

sixteenth century, women are shown to be consistently more frequent users of the incoming -(e)s form in the south than men, suggesting perhaps that women were more apt to adopt forms that were in the process of being generalized throughout Tudor England. In fact women turned out to be the leaders in seven out of ten Early Modern English changes which were studied by means of the CEEC corpus. We also know from present-day English that women are usually in the vanguard of linguistic change, especially of those changes that are in the process of spreading to supralocal usage. At the same time, we should not forget that, due to basic diVerences in education, a much smaller section of the female than the male population could write in Tudor England, which leaves women’s language less well represented than that of men. But there were also women—such indeed as Queen Elizabeth herself— who possessed an extensive classical education. The passage below comes from a letter written by her in 1591 to King James VI of Scotland, the man who, twelve years later, would be her successor to the English throne:

My deare brother, As ther is naught that bredes more for-thinking repentance and agrived thoughtes than good turnes to harme the giuers ayde, so hathe no bonde euer tied more honorable mynds, than the shewes of any acquital by grateful acknowelegement in plain actions; for wordes be leues and dides the fruites. ([ROYAL 1] 65)

In her personal correspondence, Queen Elizabeth chose -(e)s over -(e)th about half of the time with verbs other than have and do. In this, she clearly belonged to another generation than her father King Henry VIII (1491–1547) who, as in the following extract from a letter of 1528, had not employed the incoming -(e)s form even in the intimacy of his love letters to Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth’s mother:

And thus opon trust oV your short repaire to London I make an ende oV my letter, myne awne swettehart. Wryttyn with the hand oV hym whyche desyryth as muche to be yours as yow do to have hym—H Rx ([HENRY 8] 112)

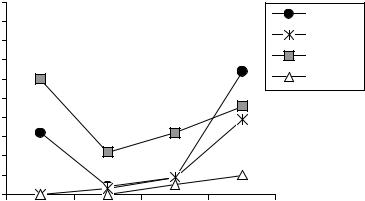

The CEEC material can also be used to give us an idea how the change progressed geographically at this time. Figure 7.2 presents the relative frequency of the thirdperson singular -(e)s from the late Wfteenth to the early seventeenth centuries. As -(e)s originates from the north it is only natural that it should be more frequent in the northern texts than it is elsewhere in the early part of the period. It is therefore somewhat surprising to Wnd that, for the better part of the sixteenth century, this higher frequency is no longer in evidence. We can assume, therefore, that the pressure of the southern -eth norm must have had an eVect on the general usage among the literate section of the people in the north; we will explore this in more detail in the next section.

As Figure 7.2 also indicates, with the exception of the late Wfteenth century, -(e)s is not much used in the capital, either at Court or in the City of London, until the

mapping change in tudor english 189

100 |

London |

|

90 |

||

|

||

80 |

Court |

|

|

||

70 |

North |

|

|

||

60 |

East Anglia |

%50

40

30

20

10

0

1460− |

1500− |

1540− |

1580− |

1499 |

1539 |

1579 |

1619 |

Fig. 7.2. Regional spread of -(e)s in verbs other than have and do Source: Based on Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg (2003: 178).

last few decades of the sixteenth century. This is the point when the -(e)s ending made its breakthrough in the City, and also gained ground at Court. We saw above that the Queen herself regularly used -(e)s in her personal correspondence.

But it nevertheless remains signiWcant that -(e)s should have been present in London in the late Wfteenth century. A writer’s geographical roots in the -(e)s speaking area may, for example, partly account for its early appearance in the usage attested for the capital. As Chapters 4 and 5 have noted, for example, the City of London attracted vast numbers of immigrants from the north, especially apprentices, in the late Middle Ages. Our early evidence on London English also mostly comes from merchants’ letters, and some of them we know had northern connections. This was, for instance, the case with Richard Cely, a member of the wool-exporting Cely family from London, and a frequent -(e)s user, as is indicated in the following extract from a letter written in 1480 to his brother George Cely. It is worth noting here that he also uses the zero form, and writes both he prays (as in line 2) and he pray (in line 4):

Syr, my Lord of Sente Jonys commende hym to you, and thankys yow for yowr tydyngys, and prays you of contynewans. He ys ryught glad of them, and he prays yow to remembyr hys sadyllys, styropys and spwrs, and clothe for hosyn. Aull tys at thys Whytsuntyd he pray yow that hyt may be had. ([CELY] 74)

The only region of the four examined where literate writers clearly avoided -(e)s at the turn of the seventeenth century is East Anglia. This may be connected with the fact that the area was rather self-contained with Norwich as its local centre. It

190 terttu nevalainen

may also have something to do with the availability of a third alternative, the zero form, which had been attested there from the Wfteenth century onwards. This suYxless form could also be used with have, do, and say—as in the Norfolk-based Katherine Paston’s use of ‘thy father have’ (see p. 185). Elsewhere, as we have seen, these verbs preferred -eth. Further examples can be found, for example, in a letter written by John Mounford, a local Norfolk man, to Nathaniel Bacon in 1573:

. . . and also your horce shall want no shooing, to be doone allwaies at home in your stabel, for he do dwell within haulfe a myle of Cocthorpe. But his father saye that he cannot forbeare him from his occupacion to continew with yow, but I thinke if yow doo talke with his father yow shall soone intreat him . . . ([BACON I] 56)

Despite this lag, the supralocal use of -(e)s was generalized in the East Anglian data as well in the course of the seventeenth century

-(e)th from the south

As we have seen, Figure 7.2 suggests that the southern -(e)th had made signiWcant inroads into the north in the course of the late Wfteenth and early sixteenth centuries, by which time it appears as the majority form in the personal correspondence of northerners. Nevertheless, there was clearly competition between the local northern form -(e)s and the would-be supra-local -(e)th, not least since the latter was supported by the printing press and administrative and legal documents, such as the Statutes of the Realm, which has been referred to above. Both forms were clearly known to and used by literate people in the north, although the relative proportions of this usage tend to diVer depending on the person. In the Plumpton family letters, for example, -(e)th was more common in letters written by men than it was in letters written by women, as well as being more common in the letters of highranking and professional men than in letters written by men coming from lower social orders. But northerners of course never gave up their local -(e)s form, which regained its status as the supra-local written norm at the turn of the seventeenth century in the northern data.

The -s ending, with its alternative spellings -es and -is, was also the norm in Older Scots. The Helsinki Corpus of Older Scots has no instances of the southern -(e)th before 1500, and only a couple occur in the period 1500–1570. But there is a huge increase in the use of -(e)th in the HCOS in the next period, 1570–1640, and this does not diminish signiWcantly even in the latter half of the seventeenth century. Most Scots genres at that point have at least some instances of -(e)th,

mapping change in tudor english 191

although it is clearly favoured in travelogues, handbooks, and educational and scientiWc treatises. Genre-preferential patterns can also be seen in the HC data which represents southern English from the latter half of the seventeenth century; apart from the conservative verbs do and have, which commonly retain -(e)th, other verbs also take the ending in handbooks, educational treatises, sermons, and in the autobiography of George Fox, the founder of the Quaker society, although it is particularly prominent in Richard Preston’s translation of Boethius’s De Consolatione Philosophiae (1695).

Two Scots cases from the middle period are presented below. The Wrst comes from a sermon Upon the Preparation of the Lordis Supper which was preached by the Church of Scotland minister Robert Bruce in Edinburgh in 1589. It has only one -eth form, doeth in line 2; all the other relevant forms end in -es, as in makes in line 2 and 3, and hes in lines 1 and 4. In this respect, it diVers strikingly from the sermon preached by Henry Smith in London two years later (and which was discussed on p. 187) which does not contain a single instance of -(e)s:

I call it Wrst of all, ane certaine feeling in the hart: for the Lord hes left sic a stamp in the hart of euery man, that he doeth not that turne so secretlie, nor so quietly but hee makes his owne heart to strike him, and to smite him: hee makes him to feill in his owne hart, whether hee hes doone weill or ill. (1590, [BRUCE] 4)

The second passage comes from a pamphlet entitled A Counterblaste to Tobacco which was written by King James and published in 1604. This contains an even mix of -eth and -es forms and, as such, is more anglicized than Bruce’s sermon:

Medicine hath that vertue, that it neuer leaueth a man in that state wherin it Wndeth him; it makes a sicke / man whole, but a whole man sicke. And as Medicine helpes nature being taken at times of necessitie, so being euer and continually vsed, it doth but weaken, wearie, and weare nature. ([TOBACCO] 95)

The fact that the traditional southern -eth form continued well into the seventeenth century has, as the previous chapter also noted, been explained by the process of anglicization of Older Scots especially after the Union of the Crowns in 1603. A closer look at the later seventeenth-century Scots forms reveals, however, that they come from two main categories. One consists of the familiar three verbs have, do, and say (the Wrst two of which also appear in the King James’ extract above). These make up about half of the cases. The other group consists of verbs that end in sibilant sounds such as /s/, /z/, or /$/, for example, where the suYx constitutes a syllable of its own (as in words such as ariseth, causeth, increaseth, presseth, produceth, etc.). Only one third of the cases are not linguistically regulated in this way.

192 terttu nevalainen

linguistic motives for-(e)s

The relevance of the verb-Wnal consonant to the choice of suYx also emerges in the southern English data. The incoming -(e)s form was favoured by verbs ending in a stop, and in particular by the presence of a Wnal /t/ (e.g. lasts) and /d/ (leads). In contrast, and just as in the Older Scots corpus, -eth tended to be retained in verbs ending in a vowel and, as noted above, particularly, in verbs ending in a sibilant or sibilant-Wnal aVricate: /s/ (compasseth), /z/ (causeth), /$/ (diminisheth), /t$/ (catcheth), and /dZ/ (changeth). After a sibilant the suYx always preserves its vowel, thereby forming an additional syllable.

A means of adding an extra syllable to a verb is, of course, a very useful device in maintaining a metrical pattern in drama and poetry. The alternation between the two suYxes in the following extract from Act Vof Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew can, for instance, be explained by metrical considerations. The suYx -eth in oweth is accorded a syllabic status, while a non-syllabic reading is given to -s in owes:

Such dutie as the subiect owes the Prince Euen such a woman oweth to her husband.

(V. ii. 156–7)

But, we might ask, why could a syllabic -es not be used in these contexts, too? Corpora give no straightforward answer to this question, and we need to turn to contemporary Tudor commentators to see whether they could give any clues as to how to interpret this variation. After all, the spellings -es and -eth in medieval texts suggest that both these third-person endings once contained a vowel before the Wnal consonant. Today the vowel is no longer pronounced except with sibilant-Wnal verbs (as in it causes).

Vowel deletion of this kind is not restricted to third-person verbal endings but it can also be found in the plural and possessive -(e)s endings of nouns, as well as in the past tense and past participle -ed forms of verbs. Previous research suggests that plural and possessive nouns were the Wrst to lose the /@/ vowel in these positions, and this took place in all words except for those ending in sibilants. This deletion process started in the fourteenth century and was gradually completed over the course of the sixteenth. The process was slower with the past-tense and pastparticiple forms of verbs in which the suYx -ed was retained as a separate syllable in many formal styles of usage until the end of the seventeenth century. It still of course continues to be retained in adjectival forms such as learned, as in a learned monograph, a learned society.

mapping change in tudor english 193

In the third-person singular present-tense endings, the vowel loss happened earlier in the north of England than in the south. The process was faster in colloquial speech than in other registers, and was only blocked, as we have seen, by the presence of word-Wnal sibilants. The southern -(e)th ending was, for example, the regular third-person suYx for John Hart, an early (London-based) phonetician who has already been discussed in Chapter 6. His proposals for spelling reform appeared between 1551 and 1570 and, importantly, contained detailed transcriptions of speech. In this context, Hart is, importantly, the Wrst reliable sourceto distinguish between the full and contracted variants of -eth. The latter he restricts to colloquial speech, and his transcriptions only contain a few instances of /s/ (as in the words methinks, belongs), but none of /es/. This suggests therefore that -(e)s had lost its vowel in non-sibilant contexts by the mid-sixteenth century. Many commentators, as a result, did indeed regard -s as a contracted form of the syllabic -eth.

This contemporary evidence also indicates that the contracted forms of both -(e)th and -(e)s had become current in the course of the Tudor period, and that -s was, by this point, largely used as a contracted form. Phonologically, the contracted -s also had an advantage over the dental fricative in -th (i.e. /u/) in that it was much easier to pronounce after verbs ending in /t/ and /d/, as in sendeth, for example, or sitteth. Although the Tudor English spelling system cannot be relied on to display vowel deletion except with writers with little formal education, the corpus evidence shows a general preference for -(e)s with verbs ending in the stops /t/ and /d/.

We are now in a better position to interpret the CEEC Wndings in Figure 7.2. It is probably the full and uncontracted -es form which reached London in the late Wfteenth century. Like some other northern features which are also attested in London English at this time, it failed to gain wider acceptance. However, the second time -(e)s surfaced in the capital, in the sixteenth century, it involved vowel contraction, which was now common with singular third-person verb inXections in the south as well. In its short, contracted form, the originally northern suYx hence found its way into the supra-local variety used by the literate people of the time. The traditional southern form -eth had meanwhile gained a Wrm position in formal contexts as, for instance, in liturgical speech, but it was also retained in many regional dialects.

you and thou

Verbal endings are by no means the only linguistic systems in Tudor English which make use of the same form for both the solemn and the rural. One of

194 terttu nevalainen

the best known cases is the alternation between the second-person singular pronouns you and thou.4 Apart from its traditional liturgical use, as in the Lord’s Prayer, thou has continued as a regional form until the present day especially in the north and west of England. Nevertheless, and as earlier chapters in this volume have already explored, English, just like the other Germanic languages, used to have two second-person pronouns, thou in the singular and you in the plural. In Middle English (see p. 107), the use of the plural you started to spread as the polite form in addressing one person (cf. French vous, German Sie). Social inferiors used you to their superiors, who reciprocated by using thou. In the upper ranks you was established as the norm among equals. Thou was generally retained in the private sphere, but could also surface in public discourse. As forms of address are socially negotiable, however, no rigid rules apply, and the story of the two pronouns is rather more complex in its pragmatic details.

The Helsinki Corpus tells us that thou continued to recede in Tudor English. Comparing an identical set of genres and about the same amount of text, we learn that the use of the subject form thou dropped from nearly 500 instances in the Wrst Early Modern English period (1500–1570), to some 350 in the second (1570–1640). It is noteworthy, however, that a full range of genres continued to use thou in the sixteenth century: not only sermons and the Bible but also handbooks, educational treatises, translations of Boethius, Wction, comedy, and trials. The example below, on how to ‘thresshe and wynowe corne’, comes from John Fitzherbert’s The Boke of Husbandry of 1534; only the pronoun thou occurs in the text included in the HC.

This whete and rye that thou shalt sowe ought to be very clene of wede, and therfore er thou thresshe thy corne open thy sheues and pyke oute all maner of wedes, and than thresshe it and wynowe it clene, & so shalt thou haue good clene corne an other yere. ([FITZH] 41)

Thou also occurs in sermons and the Bible, as well as the Boethius translations, which are sampled from all three Early Modern English periods in the Helsinki Corpus. Henry Smith’s sermon discussed on p. 187 can, for example, be used to illustrate the familiar biblical use, as in ‘Loue . . . thy neighbour as thy selfe’.

4 Unless otherwise stated, you here stands for the lexeme, which comprises all the case forms of the pronoun: ye, the traditional subject form, largely replaced by you in the course of the Tudor period; you, the form traditionally used in the object function; and the possessive forms your and yours. Similarly, thou stands for the subject form thou; the object form thee ; and the possessive forms thy and thine.

mapping change in tudor english 195

Although the Boethius translations display widely diVerent wordings, the use of thou is common to all of them, as in ‘that thou a litel before dyddyst defyne’ in the translation written by George Colville in 1556 (see further p. 207), and ‘as thou hast defynd a lyttle afore’ in that written by Queen Elizabeth herself in 1593 (both further discussed on p. 207).

The rest of the HC genres that contain thou suggest, however, a process of sociodialectal narrowing in its use during the seventeenth century: in comedies and Wction, for example, thou is commonly put in the mouths of servants and country people. To some extent, thou also continues to be used by social superiors addressing their inferiors. In seventeenth-century trials, for instance, the judge could still take recourse to thou when trying to extract information from a recalcitrant witness. The example below records part of Lord Chief Justice JeVreys’s interrogation of the baker John Dunne in the trial of Lady Alice Lisle in 1685. Note that apart from the formulaic prithee, the judge begins by using you:

L. C. J. Now prithee tell me truly, where came Carpenter unto you? I must know the Truth of that; remember that I gave you fair Warning, do not tell me a Lye, for I will be sure to treasure up every Lye that thou tellest me, and thou may’st be certain it will not be for thy Advantage: I would not terrify thee to make thee say any thing but the Truth: but assure

thy self I never met with a lying, sneaking, canting Fellow, but I always treasur’d up 5 Vengeance for him: and therefore look to it, that thou dost not prevaricate with me, for

to be sure thou wilt come to the worst of it in the end?

Dunne. My Lord, I will tell the Truth as near as I can. (1685, State Trials [LISLE IV] 114, C1)

This passage suggests that in a highly status-marked situation such as a public trial, where forms of address are derived from social identity, thou co-occurs with terms of abuse, threats, and other negative associations—here speciWcally Lord Chief Justice JeVrey’s accusations of lying. This had also been the case earlier in the Tudor period.

Moving on to private spheres of usage, in the seventeenth century thou can be found in letters exchanged by spouses, and parents may use it when addressing their young children. But in these cases, too, mixed usage prevails, with you clearly as the usual form, and thou often appearing in formulaic use at the beginning and end of the letter. In the following extract from a letter written in 1621 by Thomas Knyvett to his wife, you appears when he is discussing the choice of cloth patterns, but thou is used in the more intimate (if rather conventional) closing of the letter. Even there you intervenes in the last sentence:

196 terttu nevalainen

I haue been to look for stufe for yr bedde and haue sent downe paternes for you to choose which you like best. Thay are the neerest to the patourne that wee can Wnde. If you lack anything accept [except] my company you are to blame not to lett me knowe of it, for my selfe being only yours the rest doe followe. Thus in hast Intreating the to be

5merry and the more merry to think thou hast him in thy armes that had rather be with you then in any place vnder heaven; and so I rest

Thy dear loving husband for ever Tho: Knyvett. ([KNYVETT] 56–57)

Knyvett was a Norfolk gentleman. Lady Katherine Paston, writing to her 14-year old son in 1625 to inform him that ‘thy father haue bine very ill’ (see p. 185), also came from Norfolk. The writers using thou at all in their private letters at the time were, as these examples suggest, typically members of the country gentry. In contrast, the overwhelming majority of close family letters written by the literate social ranks only have you throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As the Corpus of Early English Correspondence (CEEC) bears witness, Henry VIII always addressed his ‘own sweetheart’, Anne Boleyn, as you rather than thou in his love letters to her, but so did the wool merchant John Johnson, writing to his wife Sabine Johnson in the 1540s. The same is true of King Charles II, who consistently addressed his little sister, dearest Minette, as you in the 1660s. Writing to her Wance´ (and later her husband) Sir William Temple in the 1650s, Dorothy Osborne used you well over 2,500 times. Thou (or rather thee) appears only twice, after they were married, as in the following extract from a letter of 1656:

Poor Mr Bolles brought this letter through all the rain to day. my dear dear heart make hast home, I doe soe want thee that I cannot imagin how I did to Endure your being soe long away when your buisnesse was in hand. good night my dearest, I am

Yours D. T. ([DOSBORNE] 203)

linguistic consequences

As you came to be used in the singular as well as in the plural, the traditional number contrast was lost in the second-person pronoun system in supra-local uses of English. As a result, as in Modern English, it is not always clear whether you refers to one or more people. DiVerent varieties of English have remedied the situation by introducing plural forms such as youse (see further Chapter 11), you all, or you guys. In the eighteenth century, the distinction was often made by using

mapping change in tudor english 197

singular you with singular is (in the present tense) and was (in the past tense); in the plural you appeared with the corresponding are and were. This practice was, however, soon condemned as a solecism—ungrammatical and improper—by the prescriptive grammarians of the period (see further Chapter 9).

Another consequence of the loss of thou was an additional reduction in person marking on the English verb. As shown by the extract from Lord Chief Justice JeVreys (discussed on p. 195), the use of thou as the subject of the sentence entailed the verb being marked by the -(e)st ending, as in JeVrey’s s thou tellest, thou may’st, thou dost. Marking the second-person singular was systematic in that it also extended to auxiliary verbs (e.g. thou wilt), which otherwise remained uninXected for person. It is, in fact, the second-person singular that justiWes us talking about a system of person and number marking in English verbs, because it also applies to past-tense forms (as in thou . . . didst deWne). As we saw in the previous section, the third-person singular endings -(e)th and -(e)s only applied to present-tense forms in Tudor English, just as -(e)s does today.

Adding the second-person ending could, however, lead to some quite cumbersome structures in past-tense forms. George Colville, for instance, decided against having thou *deWnedst in his Boethius translation in 1556, opting instead for thou didst deWne. This is also the case for many other texts, such as the

1552 Book of Common Prayer, which preferred didst manyfest to *manifestedst in the collect given below; this phonotactic use of the auxiliary was retained and even augmented in the revised version of the Prayer Book in 1662:

O God, whych by the leadinge of a starre dyddest manyfeste thy onely begotten sonne to the Gentyles; Mercyfully graunt, that we which know thee now by fayth, may after this lyfe haue the fruicion of thy glorious Godhead, through Christ our Lorde.

As we have established a connection between the second-person pronoun thou and the use of do, let us now turn to this auxiliary verb.

the story of do

The rise of do is a grammatical development which is, in histories of the language, particularly associated with Tudor English. But even after decades of empirical work, some key issues in the history of this auxiliary continue to puzzle scholars. Where in England did it come from? Does it go back to