- •Contents

- •Предисловие

- •Методическая записка

- •Britain in ancient times. England in the Middle Ages.

- •1. The Earliest Settlers

- •3. The Anglo-Saxon period

- •The origin of day names

- •4. The Danish Invasion of Britain

- •5. Edward the Confessor

- •1. Beginning of the Norman invasion

- •2. The Norman Conquest

- •3. England in the Middle Ages

- •Church and State

- •Magna Carta and the beginning of Parliament

- •4. Language of the Norman Period

- •5. The development of culture

- •First universities

- •1. General characteristic of the period

- •2. Society

- •Peasants’ Revolt

- •3 Economic development of England

- •Agriculture and industry

- •4. Growth of towns

- •5. The Hundred Years War

- •6. Wars of the Roses

- •Geoffrey Chaucer

- •William Caxton

- •Music, theatre and art

- •Assignments (1)

- •1. Review the material of Section 1 and do the following test. Check yourself by the key at the end of the book. Test 1

- •2. Get ready to speak on the following topics:

- •III. Topics for presentations:

- •The English Renaissance

- •1. General characteristic of the period

- •2. The Great Discoveries

- •3. Absolute monarchy

- •4. Reformation

- •5. Counter-Reformation

- •6. Renaissance humanists

- •Elizabethan Age

- •1. The first playhouses

- •2. Actors and Society

- •3. London theatres

- •4. William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

- •5. Shakespeare and the language

- •1. The reign of James I

- •2. Strengthening of Parliament

- •3. Charles I and Parliament

- •4. The Civil War

- •5. Restoration of monarchy

- •6. Trade in the 17th century

- •7. Political parties

- •S 8. Science, Art and Music cience

- •J 9. Literature ournalism

- •Assignments (2)

- •I. Review the material of Section 2 and do the following test. Check yourself by the key at the end of the book. Test 2

- •II. Get ready to speak on the following topics:

- •3. Topics for presentations:

- •Britain in the New Age. Modern Britain.

- •1. The Glorious Revolution

- •2. Political and economic development of the country

- •3. Life in town

- •4. London and Londoners

- •5. The Industrial Revolution

- •6. The Colonial Wars

- •7. The Development of arts

- •8. The Enlightenment

- •1. Napoleonic Wars

- •2. The political and economic development of the country

- •3. Romanticism

- •4. Art and artists

- •5. Victorian Age

- •Victorian Literature

- •1. The beginning of the century

- •2. Britain in World War I

- •3. Social issues in the 1920s

- •4. The General Strike and Depression

- •5. The Abdication

- •6. Britain in World War II

- •7. Britain in the post-war period

- •8. The fall of the colonial system

- •9. The Falklands War

- •10. Britain in international relations

- •11. Britain’s economic development at the end of the century

- •12. Social issues

- •13. 20Th-century literature

- •14. The development of the English language Changes in the language

- •In recent decades the English language in the uk has undergone certain phonetic, lexical and grammatical changes:

- •The spread of English. Variants of English.

- •Spelling differences

- •Phonetic differences

- •Lexical differences

- •Grammatical differences

- •Assignments (3)

- •I. Review the material of Section 3 and do the following test. Check yourself by the key at the end of the book. Test 3

- •II. Get ready to speak on the following topics:

- •III. Topics for presentations:

- •Cross-cultural notes Chapter 1

- •1. Iberians [aI'bi:rjRnz] – иберы/иберийцы (древние племена, жившие на территории Британских островов и Испании; в III–II вв. До н.Э. Завоеваны римлянами и романизированы.

- •Chapter 2

- •Chapter 3

- •Chapter 4

- •16. William Byrd [bR:d], Thomas Weelkes ['wi:lkIs], John Bull [bul] – Уильям Бэрд, Томас Уилкис, Джон Булл – английские композиторы конца XVI и начала XVII в. Chapter 5

- •8. Dark Lady – Смуглая Леди, незнакомка, часто упоминаемая в сонетах у. Шекспира. Chapter 6

- •Chapter 7

- •Chapter 9

- •Key to Tests

- •Электронный ресурс:

- •119454, Москва, пр. Вернадского, 76

- •119218, Москва, ул. Новочеремушкинская, 26

The origin of day names

Day names |

Germanic god(dess) |

His / her status |

Roman / Greek gods |

Planets and stars |

Monday |

– |

– |

– |

the Moon |

Tuesday |

Tiw |

The god of war |

Mars / Ares |

– |

Wednesday |

Woden |

The god of commerce |

Mercury / Hermes |

– |

Thursday |

Thor / Thur |

The God of thunder |

Jupiter / Zeus |

– |

Friday |

Frigg / Freya |

Woden’s wife / the goddess of prosperity |

– |

– |

Saturday |

– |

– |

– |

the Saturn |

Sunday |

– |

– |

– |

the Sun |

The Anglo-Saxon word-stock consisted mainly of words of the Germanic origin. Most of them have correlations in the Indo-European languages:

Words belonging to the Indo-European Family of languages

Latin |

Modern German |

Old English |

Modern English |

Russain |

pater |

Vater |

fWder |

father |

(патриарх) |

mater |

Mutter |

modor |

mother |

мать |

frater |

Bruder |

broTor |

brother |

брат |

unus |

ein |

an |

one |

один |

duo |

zwei |

tu, twa |

two |

два |

tres, tria |

drei |

Þri, Þrie |

three |

три |

junior |

jung |

GeonG |

young |

юный |

novus |

neu |

neowe |

new |

новый |

dies |

Tag |

dWG |

day |

день |

The invaders were engaged in farming and cattle-breeding. The names of Anglo-Saxon villages usually had the root ham meaning ‘home, house’ or ‘protected place’: Nottingham, Birmingham. The Saxon ton stood for ‘hedge’ or ‘a place surrounded with a hedge’, as in Brighton, Preston, Southampton. The Saxon for ‘fortress, town’ was burG or burh which we now see in Canterbury, Salisbury, Edinburgh; feld meant ‘open country, field’ and it is seen in the names of Sheffield, Chesterfield, Mansfield.

4. The Danish Invasion of Britain

Danish raids

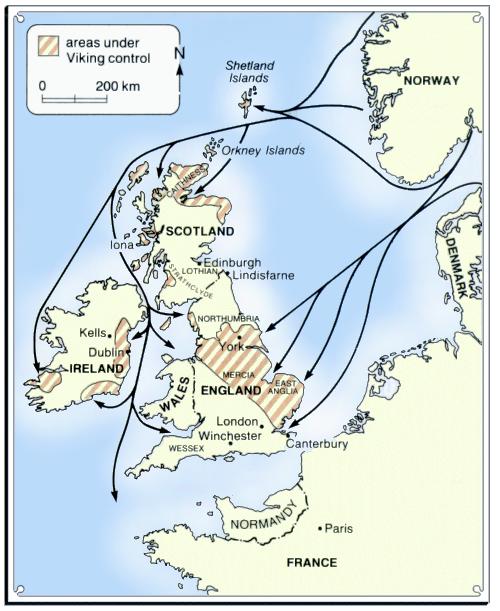

From the end of the 8th and then during the 9th and the 10th centuries Western Europe faced a new wave of barbarian attacks. (See Map 5.) The barbarians came from the North – Norway and Denmark – and were called Northmen. In different countries they were also known as the Vikings, the Normans and the Danes. The word Viking, or pirate was used by their victims and referred equally to the invaders from Norway and Denmark. As Britain was mostly raided from Denmark, in British history the invaders came to be known as the Danes.

Map 5

(From David MacDowell. An Illustrated History of Britain, Longman.)

The expansion of the Scandinavians is a European phenomenon, of which the raids on England and Ireland made only one part. Although they mostly lived in tribes, they were not totally barbarians. They were involved in trade and had regular ties with the nations living to the west and south. Many adventurers must have heard stories about the fertile lands and the rich monasteries overseas which were easy to plunder. The Northmen were well-armed skilful warriors and sailors and could easily cross the sea in search of fortune. But although they were prepared to fight, they usually aimed not at fighting but at getting loot. At the time, Ireland was the chief gold producing country of Western Europe. Moreover, it had not been invaded either by the Romans or the Anglo-Saxons. Now it was one of the first countries to be raided by the Norwegians.

In 793 the Danes carried out their first raids on Britain. In the three successive years they devastated three of England’s most holy places – Lindisfarne, Jarrow and Iona – with the treasures their monasteries possessed. The earliest raids were for plunder only. Cattle was driven off, houses were burnt, monasteries plundered and people slain. Then the invaders would return home for the winter. But a big raid on Kent in 835 opened three decades in which attacks came almost yearly, and which ended with the arrival of an invading army. Thus began the fourth conquest of Britain.

The struggle of England against the Danish attacks lasted over 300 years. During that period of time over half of England was occupied by the invaders and then regained by the English again. The Danish raids were successful because the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had neither a regular army nor a fleet of ships in the North Sea to resist the invaders. Besides, there were few roads and fortresses as the Anglo-Saxons had destroyed them. Thus, even if a settlement resisted the Danes for some time, it took their messenger several weeks to reach the nearest king and bring help. Soon the Danes conquered Northumbria, East Anglia and Mercia. London was raided in 842 and 851, and in 872 it fell to the invaders. Only Wessex was left to face the enemy. Historically, it was Wessex that became the centre of resistance to the Danes.

King Alfred the Great

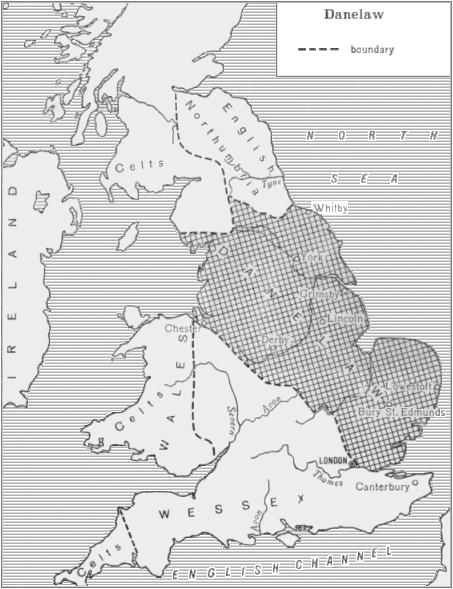

In 878 King Alfred, known in history as Alfred the Great (871-899), managed to win a decisive victory over the Danes and by the peace treaty England was divided into two parts: Wessex, ruled by Alfred, and the north-eastern part of England which was called Danelaw (Danelagh), under the rule of the Danish kings. (See Map 6.)

Map 6

(From S.D. Zaitseva, Early Britain, Moscow, 1975.)

The old Roman road from London to Wales called Watling Street served as the boundary between Danelaw and Wessex; in the North it did not even reach Hadrian’s Wall. The invaders founded new villages and towns in the north of England, which were inhabited by a mixed population of the English and the Danes.

In the Danelaw, the Danes established a society of their own governed by the Danish law. Even when the Danelaw was christianized and brought under English rule, there remained certain peculiarities: land measurement, law and social differentiation.

In 886 King Alfred the Great began to win back Danish-occupied territory by capturing the former Mercian town of London. Four years later he introduced a permanent militia and army. Alfred the Great was

the first English king to establish a regular army: all noblemen and free peasants were trained to fight. The only way of combating raids from the sea was to build ships. Alfred is said to have founded the English navy. He built ships, which were bigger than the Vikings’, carrying 60 oars or more. The places that could be easily attacked by the enemy were fortified. By the late 880s Wessex was covered with a network of roads and burghs, or public strongholds which could be described as planned fortified towns. The neighbouring landowners were responsible for maintainig the fortifications. In return, they were able to use the defences for their own purposes. The 33 fortified towns soon began to play an important part in the local rural economy.

King Alfred devoted the last ten years of his life to reviving literacy and learning in the country. He carried out his programme of education through court intellectuals and priests who were all obliged to know Latin. Alfred’s own contribution to this programme was one of his greatest achievements. He was the only English king before Henry VIII who wrote and translated books. King Alfred drew up a code of Anglo-Saxon laws and translated into English Bede’s Ecclesiastical History as well as the Bible. To him the English owe the famous Anglo-Saxon Chronicle which may be called the first prose in English literature. King Alfred died in Winchester, the capital of Wessex, in 901. He is the only king in English history called ‘the Great’.

End of the Danish rule

At the end of the 10th century the Danish invasions were resumed. The English tried to buy off the Vikings, and as a result, the Danes imposed on them a heavy tax called the Danegeld in 991. In that year alone, 10,000 pounds of silver were paid.

A new form of local government was introduced at about the same time. The country was divided into shires with one of the king’s local bailiffs (‘reeves’) in each shire appointed ‘shire-reeve’ or sheriff. The sheriff was responsible for collecting royal revenues, in the shire court he announced the king’s will to the local noblemen and took an active part in everyday business. Sheriffs belonged to the growing community of local nobility.

At the beginning of the 11th century the whole of England was conquered by the Danes. The Danish king Cnut, or Canute, became king of England, Denmark and Norway (1016-1035). Canute preserved many of the old Saxon laws collected by Alfred. He became a Christian and a protector of monasteries. Although Canute made England his residence, he often had to leave England for Denmark. Canute had to make English government function during his absence that is why he divided the kingdom into 4 earldoms: Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria and East Anglia. The king appointed an earl to rule an earldom. Gradually, the earls became very powerful. They were both Danes and Anglo-Saxon noblemen. Supported by the Anglo-Saxon feudal lords, Canute reigned in England until he died.

Culture and language of the period

The influence of the Danes on the development of English culture and the language should not be underestimated. During the Danish invasion of England, the language underwent considerable changes. The Danes were of the same Germanic origin as the Anglo-Saxons themselves and came from the same part of the Continent. As the roots were the same in English and Danish and the languages assimilated, case endings were dropped and new grammar forms developed to show relations of words. The dropping of endings meant that the stress was changed, the sound and rhythm of the language became different. Many English words are of the Scandinavian origin:

-

English

Scandinavian

fellow

feolaGa

husband

husbonda

law

laGu

wrong

wrang

to call

kalla

to take

taka

The Scandinavian borrowings in English are such adjectives as happy, low, loose, ill, ugly, weak; the nouns sister, sky, window, leg, wing, harbour. The names of Danish settlements often ended in –by or –toft/thorp(e) which meant ‘village, settlement’. Thus we have Derby, Grimsby, Whitby, Lowestoft, etc.

Old English was a synthetic language. It expressed relations between words and expressed other grammatical meanings with the help of suffixes, prefixes and interchanges in the root. The noun had the categories of number, gender (masculine, feminine, neutral), declension (ending in different letters), and case (Nominative, Genitive, Dative, Accusative). Strong and weak verbs were conjugated in the Present and the Past. A future action was expressed by means of a Present tense. During the Danish invasion prepositions and pronouns were used more often than before.

`