Body & Society-2005-Crossley-1-35

.pdf

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 11

may be necessary, for purposes of certain types of research, to break these ensembles down into their constituent techniques. If we were studying health and fitness, for example, we might want to break ‘exercising’ down into finer categories such as gym work and swimming, or even ‘2 12 reps bench press’ and ‘20 lengths front crawl’. We may even need to tease out the peculiarities of the way in which the technique is performed: e.g. bench press with arms parallel and feet touching the ground. It is not always necessary to chase the description down to this level, however. Identification of the basic ensemble may be sufficient. My above-mentioned survey includes a mix of specific body techniques and ensembles but for economy of expression I will use ‘RBT’ to refer to both.

It is my contention that practices of body modification/maintenance are best understood in terms of RBTs. I have three reasons for this. First, the concept of RBTs entails that ‘bodies’ are maintained and modified by way of bodily effort and embodied competence. We thus both avoid dualism and thematize reflexivity. Second, the concept encourages us to identify the ‘mindful’ and social aspects of embodied activity (e.g. know-how and understanding), not subordinating those aspects to the symbolic meaning bestowed by representations, discourse, consciousness, etc., and not reducing embodied activity to mere mechanical behaviour. Third, the concept is sufficiently concrete to facilitate empirical analysis and sufficiently rich for that to include both ethnographical/phenomenological investigation of the doing of RBTs, their lived dimension (see Crossley, 2004a; Wacquant, 2004), and also more quantitative explorations of them. As forms of practical understanding, RBTs need to be understood qualitatively, in a phenomenological manner. And they are also thematized within projects and narratives which call for qualitative investigation. But qua social techniques they are diffused and distributed through society. They can be observed, categorized, enumerated and tested for statistical association both with one another and with other social phenomena. They thus call for and admit quantitative analysis also.

Before we can push ahead with this concept, however, we need to reflect upon the role of ‘purpose’ in relation to RBTs. I have said that RBTs are body techniques whose primary purpose is to act back upon the body so as to modify or maintain it. At its most basic this entails that RBTs are generic body techniques which an agent annexes, in a specific context, for the explicit purpose of (perhaps amongst other things) modifying their body in a particular way: for example, in an effort to lose weight they elect to take a walk once a week. In many cases, however, reflexive purposes have generated either dedicated techniques or dedicated variations upon generic techniques. ‘Jogging’, for example, is a form of

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

12 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

running adapted to serve the purpose of exercise. In contrast to a mad dash for the bus, a jog entails that I pace myself (a temporal modification), adjust my breathing and ‘settle into’ a comfortable and efficient posture and stride. Jogging embodies a particular temporal projection (I will run for this long). It is oblivious to the urgency that animates the person running after the bus. And in these respects it embodies the purpose of running for the benefit of running. When I jog I relate to my environment in a different way. Perhaps I lengthen my step, utilizing my body differently in order to utilize the ground differently; simultaneously utilizing the ground differently in order to utilize my body differently, pushing it towards the ‘burn’ that I am seeking. Street-lights and other random objects become stage markers, triggering alterations in pace and direction, for a journey whose only goal is transformation of the ‘vehicle’ itself and whose success is measured against this goal. In this way, both agent and environment are instituted10 in a specific ‘jogging-like’ manner by way of a dedicated RBT. Moreover, in contrast to the person running after the bus, whose fear of missing the bus and looking silly often leads them to ‘disguise’ their sprint as much as possible, I commit myself publicly to my jog. My action is accountable. I embody a social type or role, ‘the jogger’. And I am able to do this because jogging is not my private invention but rather a socially emergent and publicly known technique that belongs to my society’s repertoire. I have selected and learned from this repertoire and for this reason everybody knows what I am doing when I stagger past them.

Purpose also enters into the analysis of reflexive body techniques in the respect that the body can be modified for different reasons. One might modify one’s body for reasons of health, beauty, sporting success, etc. Again, this might involve significant permutations of an apparently singular technique. Bodybuilders, powerlifters and individuals who want to ‘tone up’ and ‘trim down’ might each use dumbbells and barbells, for example, and might even do the same exercises (bench press, squat, etc.). However, the way in which they do those exercises will vary. The ‘toner’ will tend to do a high number of repetitions with weights they can quite easily lift because this is good for toning; the powerlifter will do relatively few reps with a weight that is very heavy for them because this increases strength; the bodybuilder, who is concerned to increase muscle bulk but also muscular definition and ‘rips’, will use a combination of the two. Furthermore, both of the latter two will tend to work out for much longer in any weekly cycle. We need to be mindful of these differences when studying RBTs.

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 13

Body Techniques and Selfhood

Reflexive body techniques play a central role in the construction of a reflexive sense of self; that is, in the process whereby the agent turns back upon their self, effecting a split between what Mead (1967) calls ‘I’ and ‘me’. Whenever we dress ourselves, wash ourselves, exercise, etc., we effect this split. We act towards ourselves in such a way that we become objects for ourselves. Qua active agent (‘I’) we act upon ourselves as a passive object (‘me’). The rhythm by which we vacillate between I and me in these activities will vary according to the body technique in question. An agent on a long run might lose their self in their run for long periods, immersed in the pre-reflectiveness of the ‘I’ and never appearing before their self as ‘me’ until they finish. An agent who is cleaning their teeth, by contrast, might be rocking constantly between the positions of the brushing ‘I’ and the brushed ‘me’. In all cases, however, as both Mead and Merleau-Ponty (1962) emphasize, I and me remain distinct. If I touch my own hand, to use Merleau-Ponty’s (1962) example, I always reach a point at which the experience shifts from that of touching to that of being touched. The two experiences never coincide and, as such, I never coincide with myself. I am always split (Crossley, 1996, 2001). So it is with all reflexive body techniques. I and me vacillate and interact but never coincide. Even as I look in the mirror – the use of the mirror itself being an RBT11 – the lived I who perceives and the perceived ‘me’ remain separated. ‘I’ see ‘my body’ (me) but that external image does not coincide with the lived experience that confronts it. As Merleau-Ponty puts it:

At the same time that the image of oneself makes possible the knowledge of oneself, it makes possible a sort of alienation. I am no longer what I felt myself, immediately to be; I am that image of myself that is offered by the mirror. . . . I leave the reality of the lived me in order to refer myself constantly to the ideal, fictitious or imaginary me, of which the specular image is the first outline. In this sense I am torn from myself . . . (Merleau-Ponty, 1968: 136)

As the mirror demonstrates, however, this is a separation that is integral to a developed sense of ‘self’ and, indeed, of self-as-embodied. The mirror, to use Merleau-Ponty’s expression, tears us away from ourselves but thereby gives us the distance from ourselves that allows us to see, perceive and form a perspective upon ourselves. The same holds for other RBTs. They turn us back upon ourselves, thematize our bodily aspect within our own embodied intentionality and thereby put us into a relationship with an objectified image of our self.

Learning reflexive body techniques is, in this respect, part of the process through which our specific sense of self is developed. By means of these techniques we learn to constitute ourselves for ourselves, practically. Learning to attend to ourselves is learning to posit ourselves for ourselves. It constitutes a

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

14 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

specific experience of self. We learn to play the role of another in relationship to ourselves, much as Mead (1967) says of play and games in infancy. Indeed, in many cases where we tend to ourselves in these ways we are precisely taking over the role of another, a parent or guardian, who once tended and cared for us in these ways. We do to ourselves what they have done for us at an earlier time and have taught us to do, applying their standards and techniques to ourselves.

Having said that RBTs facilitate the differentiation of I and me, effectively thereby constituting the self process, it is important to add that they may be selected in accordance with agents’ projects of self-development. Specific types of ‘self’ presuppose particular reflexive body techniques for their ‘practice’. Even in these cases, however, the effect of practising the technique may be to heighten the I–me distinction and shape the perception of the me in particular ways, such that RBTs are more than mere instrumental props. Techniques of weight training are deployed by the bodybuilder in pursuit of muscular gain, for example, but at the same time these techniques orient the agent towards their body in particular ways. They embody a particular attitude towards the body, that of the ‘body sculptor’, which the bodybuilder appropriates as they appropriate these techniques within their habitus. They heighten body and muscular awareness. Furthermore, RBTs can have a ritual function, serving to symbolically and ‘magically’ mark the transition of the self from one situation to another (Crossley, 2004c). As rituals, body techniques have the power to transform imaginative and affective structures of intentionality (in the phenomenological sense), thereby situating those who practise them differently. We capture this notion colloquially when we refer to the Friday-night rituals through which people prepare themselves for a night out (washing, making up, applying aftershaves and deodorants, dressing and doing their hair). Performing these techniques, in the manner of a ritual, is part and parcel of the way in which agents put themselves ‘in the mood’ for a night out, effecting an existential (affective, imaginative, cognitive) transition from their mundane, workday mode to their ‘soirée’ self. Similarly, Sweetman’s (1999) work on tattooing and piercing suggests that these rituals mark a symbolic transition for those who undergo them, allowing these agents to effect transformations of their self.

Change, transformation and trajectory are important here; but so too are conservation and repetition. Many of the above-mentioned techniques are oriented towards preserving and maintaining a particular aspect of self. Furthermore, they form part of a routine. They are repeated on a daily, weekly, monthly and/or yearly basis. Certain technical interventions, such as a tattoo or cosmetic surgery, might serve to mark a new chapter in a life narrative, but others, by virtue of their repetition, function to structure time in a more familiar and

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 15

safe-because-same manner. They invest the flow of lived time with meaning by punctuating it, but this meaning centres upon continuity and sameness rather than transition. It is integral to grasp this balance of reproduction and transformation in our understanding and analysis of RBTs, and indeed also the different temporal configuration that specific techniques can assume. RBTs have a spatio-temporality that is central to their meaning. This is reflected in the linguistic duality of ‘body maintenance’ and ‘body modification’, which I have employed hitherto in this paper. The former denotes techniques used repetitively, for reproductive purposes, the latter denotes techniques used to effect a specific transformation.

Why agents engage in this body work is a key question in sociology, about which most of the major perspectives in the area have something to say (see Bartky, 1993; Baudrillard, 1999; Bordo, 1993; Bourdieu, 1977, 1984; Foucault, 1980; Giddens, 1991; Shilling, 1993). I do not have the space to address this question fully here. However, it is my contention that we must approach it in a way that recognizes the great diversity of RBTs in the societal repertoire and the very different social logics that can attach to their appropriation. ‘One size fits all’ explanations, such as we get from most of the above-mentioned theorists, are deeply problematic because they fail to recognize this diversity. In what follows I will explore this issue of diversity and social logics in more detail in an effort to lay the basis for a more sophisticated approach to body work, centred upon RBTs.

Group and Technique

One of Mauss’s key contentions with respect to body techniques concerns their group specificity. This specificity is such that some techniques serve to mark out group boundaries. Indeed, where they are specifically reflexive techniques they can serve to cultivate bodily markers of collective identity. Durkheim’s (1915) famous analysis of aboriginal totemic clans, for example, places great emphasis upon the role of techniques of body marking in the construction of collective, clan identities:

They do not put their coat-of-arms merely upon things which they possess, but they put it upon their person; they imprint it upon their flesh; it becomes part of them . . . it is more frequently upon the body itself that the totemic mark is stamped . . . (Durkheim, 1915: 137)

The best way of proving to oneself and to others that one is a member of a certain group is to place a distinctive mark on the body. (Durkheim, 1915: 265)

Likewise, Bourdieu’s (1977, 1984) focus upon distinction and Elias’s (1984) upon the civilizing process both draw out forms of bodily practices, specific to social

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

16 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

groups, which alter bodily appearance and thereby distinguish and mark out those groups visually. Furthermore, as Durkheim also emphasized, techniques of body modification are sometimes employed to mark out categorical distinctions within a group, for example between males and females or adults and children.

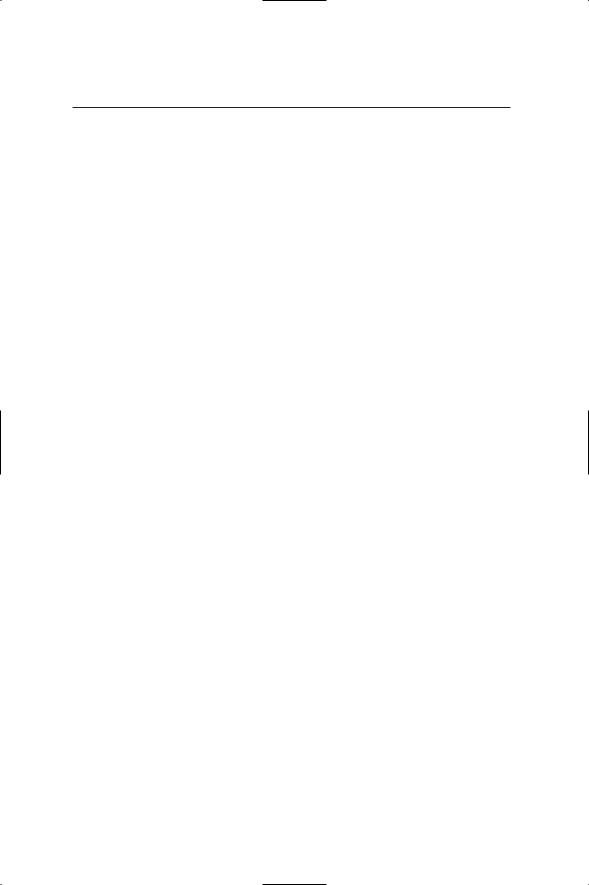

Contemporary western societies differ considerably from the totemic clans studied by Durkheim. Interestingly, however, my above-mentioned survey revealed gender to be a key factor affecting appropriation of reflexive body techniques. The survey found statistically significant and often very large differences for gender in relation to 21 (out of 40) RBTs and 6 (out of 19) forms of consultation (see Table 1). In particular, practices such as the shaving of armpits and legs, the painting of toenails and fingernails, manicure and the use of cosmetics (other than soap and shampoo) were sharply gender differentiated.

This finding bears out the claim of those who argue (i) that gender remains an extremely strong locus of social division in contemporary societies, (ii) that the body is a key site where this division is constructed and played out and (iii) that gender identity is something which is ‘done’ or ‘practised’ (e.g. Bartky, 1993; Connell, 1987). In addition, the arguments of these writers provide a strong and important lead for the analysis of RBTs, which I will return to later on. Importantly, however, the concept of RBTs, as both a theoretical and an empirical notion, allows us to further elaborate upon and explore these ideas about gender; to go beyond general theoretical claims about transformations of the body associated with, for example, ‘emphasised femininity’ (Connell, 1987) by specifying just what transformations are effected, by what means and by what types and proportions of women (relative to men). Furthermore, as I discuss in more detail below, we can begin to explore the patterns of clustering of these various techniques and, by means of this, differentiate varieties within emphasized femininity.

The low numbers of men practising certain techniques is as interesting as the high number of women in this respect. Shaved armpits are as much an affront to ‘hegemonic masculinity’ (Connell, 1987), punishable amongst men, at least in the absence of extenuating circumstances, as they are an expected standard of ‘emphasised femininity’. And a monitoring of the appropriation of these techniques among men allows us to gauge changes in masculinity. We can speculate upon all of this without recourse to the concept of RBTs, of course, but the latter provides an important and workable means for empirically operationalizing such speculation and recording change. Shifting rates of uptake for particular RBTs among men and women respectively, allow us to track shifts in dominant models of masculinity/femininity – although, of course, the meaning of changes is never self-evident and must be deduced.

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 17

Table 1 Gendered Reflexive Body Techniques

|

Female (%) |

Male (%) |

p = |

|

|

|

|

Reflexive Body Techniques |

|

|

|

Big differences (with female predominance) |

|

|

|

Shaved leg hair in last 4 weeks |

83.2 |

5 |

.000 |

Used cosmetics in last 7 days |

84.8 |

9.2 |

.000 |

Shaved armpit hair in last 4 weeks |

85.3 |

11.7 |

.000 |

Worn earrings in last 7 days |

71.2 |

7.5 |

.000 |

Worn a necklace in last 7 days |

74.9 |

30 |

.000 |

Combed hair in last 7 days |

95.7 |

59.2 |

.000 |

Worn a ring in last 7 days |

81.5 |

42.5 |

.000 |

Had or done a manicure in last 4 weeks |

53.6 |

10 |

.000 |

Painted toenails in last 4 weeks |

48.9 |

0.8 |

.000 |

Painted (hand) nails in last 4 weeks |

44.6 |

0 |

.000 |

Worn a bracelet in last 7 days |

56 |

20 |

.000 |

Small but statistically significant differences (with female predominance) |

|

|

|

Used anti-perspirant/deodorant in last 7 days |

98.4 |

89.2 |

.000 |

Used aftershave/perfume in last 7 days |

85.9 |

71.7 |

.002 |

Dieted for weight loss over last 7 days |

8.2 |

1.7 |

.001 |

Body piercings other than ears |

14.1 |

4.2 |

.005 |

Flossed in last 4 weeks |

48.9 |

30.8 |

.002 |

Sunbathed in last 12 months |

58.2 |

43.3 |

.001 |

Dyed or coloured hair in last 4 weeks |

32.1 |

5.8 |

.000 |

Used ‘Quick Tan’ lotion in last 12 months |

29.3 |

8.3 |

.000 |

Male predominance (small but statistically significant differences) |

|

|

|

Used bodybuilding supplements in last 6 months |

0 |

3.3 |

.013 |

Has 3 or more tattoos |

0 |

2.5 |

.031 |

Consultation Practices |

|

|

|

Read magazine/newspaper article on beauty tips |

57.1 |

3.4 |

.000 |

Read magazine/newspaper article on health tips |

50 |

10.8 |

.000 |

Read magazine/newspaper article on skin care tips |

48.4 |

2.6 |

.000 |

Read magazine/newspaper article on exercise tips |

36.1 |

16 |

.000 |

Read any of the above |

69.6 |

24.2 |

.000 |

Read a health-dedicated magazine |

21.7 |

5.8 |

.034 |

Consulted a beauty-dedicated website |

3.8 |

0 |

.032 |

|

|

|

|

One might expect to find similar sharp distinctions in relation to the practices of certain religious groups and perhaps subcultures of various kinds. I found no statistically significant differences pertaining to class, however. And although contemporary ethnographic studies of specific working-class communities have

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

18 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

identified aspects of a distinctly working-class body consciousness (Charlesworth, 2000; Skeggs, 1997), the available sources of secondary statistical data in this area suggest that differences in uptake of RBTs are relatively small. The General Household Survey for 1990, for example, suggests that the middle classes are slightly more likely to engage in a range of forms of exercise (reported in Social Trends, ONS, 1993). The differences are only slight in most cases, however, and each of the main forms of exercise is a minority pursuit in relation to every class, such that linking these forms of exercise to specific class identities is highly problematic. Clearly this is an area that calls for further research; research that is sensitive to the details picked up in the more qualitative forms of inquiry. It may be that we need to specify RBTs very precisely, in terms of nuances and purposes, to hook into significant class differences. In this article, however, I want to push the idea of a social distribution of RBTs in a different direction, and to identify further principles of differentiation governing their appropriation. However one defines a group, I suggest, whether one focuses upon national societies, gender and class groupings or highly specific subcultures, there is always an internal differentiation and distribution of RBTs, with its own distinct socio-logic.

In what follows I will map this out in more detail, focusing upon the group constituted by my questionnaire survey. For the purposes of my particular survey it was necessary to make certain assumptions about the purposes of particular RBTs, bracketing out further qualitative exploration of those purposes. I opted to sacrifice depth for the pursuit of breadth in circumstances where the pursuit of both was not possible. I hope it will be apparent, however, that this both yields findings not attainable by more qualitative means, and that it raises questions which, although perhaps best answered by more qualitative approaches, would not be raised in the first place by means of those methods. What follows is one half of a story but is no less valuable than the other half.

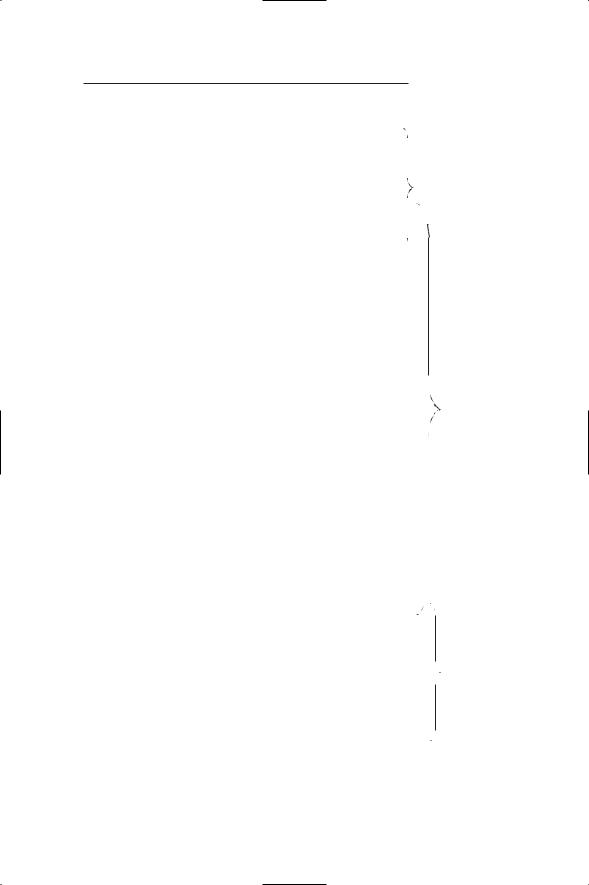

Mapping Techniques

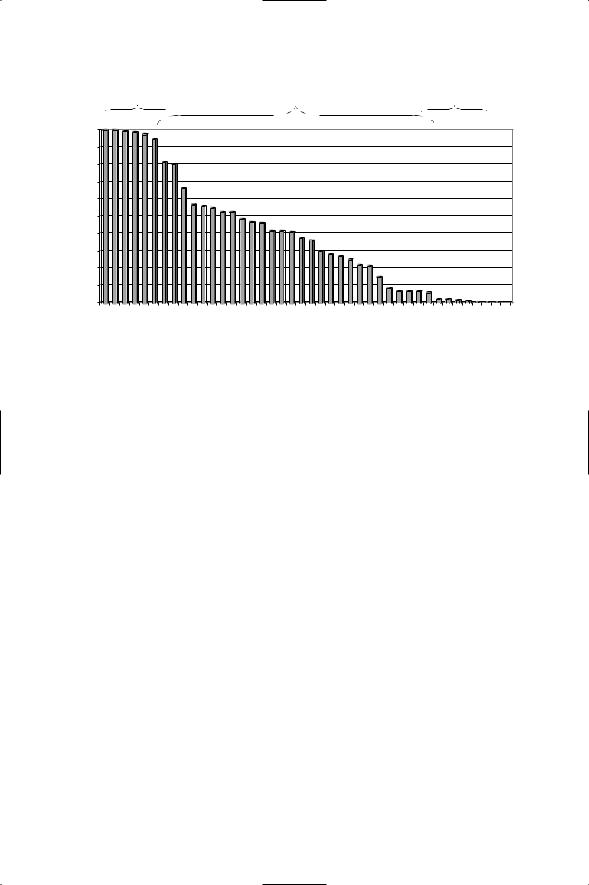

Consider, first, the frequency distribution for the techniques surveyed by my questionnaire, as given in Figures 2 and 3. The range of this distribution stretches from 100 percent, for having washed one’s hands at least once in the last seven days, through to 0.3 percent, for having had a septum or tongue piercing, or having ever used anabolic steroids for purposes of building one’s muscles. This is a continuum and any attempt to demarcate definite lines of division along it would inevitably be arbitrary. Moreover, we already know that certain of the practices are heavily gendered, such that some scores represent a mean of high

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

Mapping Reflexive Body Techniques 19

No. |

Technique |

% |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

Washed hands in last 7 days |

100 |

|

|

|||

2 |

Bath/shower in last 7 days |

99.7 |

|

3 |

Brushed teeth in last 7 days |

99.3 |

|

4 |

Washed face in last 7 days |

98.7 |

|

|

|||

5 |

Washed hair in last 7 days |

97.4 |

|

6 |

Used anti-perspirant/deodorant in last 7 days |

94.7 |

|

7 |

Combed hair in last 7 days |

81.3 |

|

8 |

Used aftershave perfume in last 7 days |

80.3 |

|

|

|||

9 |

Worn ring in last 7 days |

66.1 |

|

10 |

Worn necklace in last 7 days |

56.9 |

|

11 |

Shaved armpit hair in last 4 weeks |

56.3 |

|

12 |

Used cosmetics in last 7 days |

54.9 |

|

13 |

Sunbathed in last 12 months |

52.3 |

|

14 |

Shaved leg hair in last 4 weeks |

52.3 |

|

15 |

Used any food supplement in last 6 months |

48.4 |

|

16 |

Used a breath/mouth freshener in last 4 weeks |

46.4 |

|

17 |

Worn an earring in last 7 days |

46.1 |

|

18 |

Flossed in the last 4 weeks |

41.8 |

|

19 |

Worn a bracelet in the last 7 days |

41.8 |

|

20 |

Eaten ‘carefully’ for weight-loss reasons in last 7 days |

41.1 |

|

21 |

Used vitamin supplements in last 6 months |

37.5 |

|

22 |

Had or done a manicure in last 4 weeks |

36.2 |

|

23 |

Painted toenails in last 4 weeks |

29.9 |

|

24 |

Done between 1 and 4 hrs exercise in last 7 days |

28.3 |

|

25 |

Painted fingernails in last 4 weeks |

27 |

|

26 |

Used a sunbed in last 12 months |

25.3 |

|

27 |

Dyed or coloured hair in last 4 weeks |

21.7 |

|

28 |

Used ‘Quick Tan’ lotion in last 12 months |

21.1 |

|

29 |

Done between 5 and 9 hrs exercise in last 7 days |

15.1 |

|

30 |

Ever had cosmetic dental surgery |

8.6 |

|

31 |

Got between 1 and 3 tattoos |

6.9 |

|

32 |

Had bellybutton pierced |

6.7 |

|

33 |

Done 10 hrs exercise or more in last 7 days |

6.6 |

|

34 |

Dieted for weight-loss purposes in last 7 days |

5.9 |

|

35 |

Had nostril pierced |

2.3 |

|

36 |

Had eyebrow pierced |

2.3 |

|

37 |

Had cosmetic surgery |

1.6 |

|

38 |

Got 3 or more tattoos |

1 |

|

39 |

Had genital and/or nipple piercings |

1 |

|

40 |

Had a septum piercing |

0.3 |

|

41 |

Had a tongue piercing |

0.3 |

|

42 |

Ever used steroids for bodybuilding purposes |

0.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

Core

Zone

Intermediate

Zone

Marginal

Zone

Figure 2 Frequency Distribution of Reflexive Body Techniques

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016

20 Body and Society Vol. 11 No. 1

|

|

|

Core |

|

|

|

|

Intermediate |

Marginal |

|

|

|

|

Zone |

|

|

|

|

Zone |

Zone |

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

90 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

80 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

70 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

60 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 |

|

Figure 3 Distribution of Reflexive Body Techniques (percentages) (bar numbers correspond to RBTs named and numbered in Figure 2)

female and low male scores. I return to this latter point shortly. First, however, I want to suggest that, although any exact cut-off points would be arbitrary, we can divide this continuum into three overlapping zones. At one end of the continuum we have a core zone consisting of RBTs that are statistically normal; that is to say, which most people (e.g. 90 percent+) practise within a specifiable time-frame. At the other end of the continuum we have a marginal zone consisting of RBTs that are statistically deviant; that is, which most people (e.g. 95 percent+) do not and never have practised. Between these two zones we have what we might think of as an intermediate zone, a broad continuum of RBTs with rates of uptake that vary in the general population but which are neither so high as to be normal and thus ‘core’, nor so low as to be statistically deviant and thus ‘marginal’.

In what follows I will be using this concept of ‘zones’ to develop a differentiated account of body work in late modern societies. The appropriation of RBTs in these different zones requires different explanations, I will suggest. First, however, I want to push the idea one step further by unpacking the idea of a continuum. While useful as a point of departure, the image of the continuum is problematic on account of its linearity. We know, for example, that some body techniques are strongly gendered, such that they might qualify as ‘core’ for women, while they are ‘marginal’ for men. Likewise, we can at least speculate that other techniques in the intermediate and marginal zones will be further differentiated from one another. Marginal techniques might belong to different

Downloaded from bod.sagepub.com at Higher School of Economics on February 9, 2016