Color Atlas of Neurology

.pdf

CNS Infections

Prodromal phase

Spinal cord compression

Abducens palsy

Focal disturbances

(patient looking to right)

Hydrocephalus

Central Nervous System

Ischemic lesion |

|

Leptomeningeal |

||||

|

||||||

(tuberculous |

contrast enhance- |

|||||

arteritis) |

|

ment in MRI |

||||

III |

|

|

|

|

|

II |

|

|

|

|

|||

Tuberculoma in

brain stem

VI Tuberculous V spondylitis,

gibbus deformity

Leptomeninges full of exudate; cranial nerves barely visible

233

Caseating meningitis (basal exudate)

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

234

CNS Infections

Viral Infections

! Viral Meningoencephalitis

Aseptic meningitis is characterized by a meningitic syndrome (p. 222) that arises acutely and takes a benign course over the ensuing 1 or 2 weeks, in the absence of signs of generalized or local infection (otitis media, craniospinal abscess, sinusitis). CSF findings: A mild granulocytic pleocytosis is seen in the first 48 hours and is then transformed into a mild lymphomonocytic pleocytosis which can persist as long as 2 months after the clinical findings have regressed. The CSF protein and lactate concentrations are normal or only slightly elevated, while the CSF glucose concentration is normal or mildly decreased. The term “viral meningitis” is often used synonymously with aseptic meningitis, though, strictly speaking, the clinical picture of aseptic meningitis can also be produced by fungal, parasitic, or even bacterial infection (e. g., mycobacteria, mycoplasma, Brucella, spirochetes, Listeria, rickettsiae, incompletely treated bacterial meningitis). Aseptic meningitis may be postinfectious (HIV, rubella, measles, zoster) or postvaccinial or a sequela of sarcoidosis, Behçet disease, Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome, Mollaret meningitis, connective tissue diseases, and other, noninflammatory disorders

(meningeal carcinomatosis, contrast agents, medications, subarachnoid hemorrhage, lead poisoning).

Pathogens. Their seasonal peak frequency is shown in the following table.

Viral meningitis. Frontal or retro-orbital headache, fever, and low-grade neck stiffness usually begin acutely and last for 1–2 weeks. The CSF findings are those of aseptic meningitis, described above; the IgG index or oligoclonal IgG may be elevated.

Viral encephalitis. The meninges are usually involved concomitantly (meningoencephalitis). Acute encephalitis mainly affects the gray matter and perivascular areas of the brain. Behavioral changes, psychomotor agitation, and focal epileptic seizures may be the leading symptoms (p. 192). The CSF findings are generally as listed above for aseptic meningitis, though pleocytosis may be absent at first. Diffuse and focal EEG changes are usually seen. CT and MRI often reveal pathological changes.

Acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis (ADEM) predominantly affects perivenous regions and the cerebral white matter (leukoencephalitis). The disease takes a variable course (a monophasic course with complete resolution is among the possibilities). ADEM can occur during or after a bout of infectious disease (measles, chickenpox, rubella, influenza) or after a vaccination (smallpox, measles, mumps, polio). Both encephalitic and myelitic syndromes can occur (spastic paraparesis or quadriparesis). The white-matter lesions are demonstrated best by MRI, less well by CT.

Summer, Early Spring |

Autumn, Winter |

Winter, Spring |

All Year Round |

|

|

|

|

Arboviruses, ente- |

Lymphocytic chorio- |

Mumps |

HIV, herpes simplex |

roviruses |

meningitis virus |

|

virus, cytomegalovirus |

|

|

|

|

The viral pathogens that most commonly cause meningitis differ from those most commonly causing encephalitis and myelitis (cf. Table 30, p. 376).

Identification of pathogen: Serologic tests or isolation of the virus from throat smears (poliovirus, coxsackievirus, mumps virus; ade-

novirus, HSV type 1), stool samples (coxsackievirus, polio virus), CSF (coxsackievirus, mumps, adenovirus, arbovirus, rabies, VZV, LCMV, HSV type 2), blood (arbovirus, EBV, LCMV, CMV, HSV type 2), urine (mumps, CMV), or saliva (mumps, rabies).

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

CNS Infections

Personality change

(perseveration, apraxia, aphasia) |

Confusion |

|

(hallucinations, psychomotor hyperactivity, |

|

loss of coordination, fluctuating level of |

|

consciousness) |

Clonus

Focal signs |

|

(partial epileptic seizure) |

Extrapyramidal motor |

|

|

|

dysfunction |

|

(tonic upward gaze deviation) |

Loss of drive (anxiety, apathy, mutism)

Central Nervous System

235

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

236

CNS Infections

! Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

Pathogenesis. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV- 1) is usually transmitted in childhood through lesions of the oral mucosa (gingival stomatitis, pharyngitis). The virus travels centripetally by way of nerve processes toward the sensory ganglia (e. g., the trigeminal ganglion), where it remains dormant for a variable period of time until reactivated by a trigger such as ultraviolet radiation, dental procedures, immunosuppression, or a febrile illness. It then travels centrifugally, again over nerve processes, back to the periphery, producing blisterlike vesicles (herpes labialis). HSV-1 also causes eye infection (keratoconjunctivitis), as well as (meningo)encephalitis when it spreads via CN I and leptomeningeal fibers of CN V. There is no association between herpes labialis and HSV-1 encephalitis. Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) reaches the lumbosacral ganglia by axonal transport from a site of (asymptomatic) urogenital infection. Its reactivation causes genital herpes. In adults, HSV-2 infection can cause (aseptic) meningitis and, occasionally, polyradiculitis or myelitis. HSV-2 virus can be transmitted to the newborn during the birth process, causing encephalitis. HSV-1 encephalitis is very rare in neonates, and HSV-2 encephalitis is very rare in adults.

Symptoms and signs. Herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE) in adults begins with local inflammation of the caudal and medial parts of the frontal and temporal lobes. Uncharacteristic prodromal signs such as fever, headache, nausea, anorexia, and lethargy last a few days at the most. Focal symptoms including olfactory and gustatory hallucinations, aphasia, and behavioral disturbances (confusion, psychosis) then appear, along with focal or complex partial seizures with secondary generalization. There is usually repeated seizure activity, but status epilepticus is rare. Intracranial hypertension causes impairment of consciousness or coma within a few hours. In neonates, the inflammation spreads throughout the CNS.

The diagnosis of HSE can be difficult, especially at first. The clinical findings include neck stiffness, hemiparesis, and mental disturbances. CSF examination reveals a lymphomonocytic pleocytosis (granulocytes may predominate initially) with an elevated protein concentration;

low glucose and high lactate concentrations are only rarely found. Xanthochromia and erythrocytes may be present (hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalitis). In the first 3 weeks, the virus can almost always be detected in the CSF by polymerase chain reaction; brain biopsy is only rarely needed for identification of the viral pathogen. Lumbar puncture carries a risk if intracranial hypertension is present (p. 162). EEG reveals periodic high-voltage sharp waves and 2–3 Hz slow wave complexes as a focal or diffuse finding in one or both temporal lobes. In the acute stage of HSE, CT is normal or reveals only mild temporobasal hypointensity without contrast enhancement. Hemorrhage may appear as a hyperdense area. Sharply defined areas of hypodensity appear on CT only in the later stages of HSE. T2-weighted MRI, however, already reveals inflammatory lesions in early HSE. Thus, MRI is used for early diagnosis, CT for the monitoring of encephalitic foci and cerebral edema over the course of the disease.

Meningitis. The clinical manifestations are those of aseptic meningitis (p. 234).

Myelitis. Low back pain, fever, sensory deficit with spinal level, flaccid or spastic paraparesis, bladder and bowel dysfunction. These manifestations usually regress within 2 weeks.

Radiculitis. Inflammation of the lumbosacral nerve roots produces a sensory deficit and bladder and bowel dysfunction.

Virustatic agents. HSV infection of the CNS is treated with acyclovir 10 mg/kg (i. v.) q8h for 14–21 days. Particularly in HSE, it is important to begin treatment as soon as possible.

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

CNS Infections

Migration of virus (olfactory bulb)

Olfactory epithelium

Route of HSV-1 infection (in encephalitis)

Spaceoccupying lesion (herpes simplex encephalitis of left temporal lobe)

Viral invasion (olfactory epithelial cell)

HSV-1

Prodromal signs, |

MRI |

behavioral changes |

(contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image) |

|

Periodic slow-wave complexes, left temporal |

1s |

50 V |

|

|

|

EEG |

Central Nervous System

237

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

238

CNS Infections

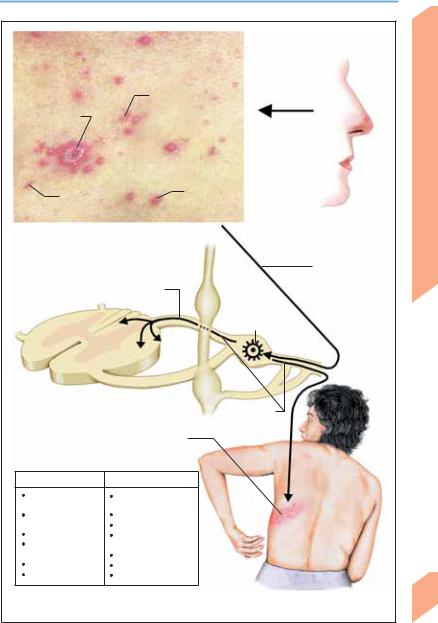

! Varicella-Zoster Virus Infection

Pathogenesis. In children, primary infection with varicella-zoster virus (VZV) usually causes chickenpox (varicella). The portals of entry for infection by droplets or mucus are the conjunctiva, oropharynx, and upper respiratory tract. The virions replicate locally, then enter cells of the reticulohistiocytic system by hematogenous and lymphatic spread (primary viremia). There, they replicate again and disseminate (secondary viremia). VZV infection is followed by immunity. VZV travels by centripetal axonal transport through the sensory nerve fibers of the skin and mucous membranes to the spinal and cranial ganglia and may remain latent there for years (ganglionic latency phase). The thoracic and trigeminal nerve ganglia are most commonly affected, but those of CN VII, IX, and X can also be involved. Spontaneous viral reactivation in the ganglia (ganglionitis) is most common in the elderly, diabetics, and immunocompromised persons (HIV, lymphoma, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, etc.). The reactivated virus travels over the axons centrifugally to the dermatome corresponding to its ganglion of origin, producing the typical dermatomal rash of herpes zoster. It may also spread to the CNS via the spinal dorsal roots (radiculitis), causing herpes zoster myelitis or meningoencephalitis. VZV attacks cerebral blood vessels by way of axonal transport from the trigeminal ganglion. Postherpetic neuralgia is thought to be due to disordered nociceptive processing in both peripheral and central structures.

Symptoms and signs. Chickenpox: After an incubation period of 14–21 days, crops of itchy efflorescent lesions appear, which progress through the sequence macule, papule, vesicle, scab within a few hours. The scabs detach in 1–2 weeks. Immunocompromised patients can develop severe hemorrhagic myelitis, pneumonia, encephalitis, or hepatitis. Acute cerebellitis in children causes appendicular, postural, and gait ataxia, less commonly dysarthria and nystagmus. CSF examination reveals mild pleocytosis and elevation of the protein concentration, or is normal, and the MRI is usually normal. VZV cerebellitis resolves slowly in most cases.

Herpes zoster begins with general symptoms (lethargy, fever) followed by pain, itching, burn-

ing or tingling in the affected dermatome(s), which are most commonly thoracic or craniocervical (special forms: herpes zoster ophthalmicus, oticus, and occipitocollaris). Within a few days, groups of distended vesicles containing clear fluid appear on an erythematous base within the affected dermatome. The contents of the vesicles become turbid and yellowish in 2–3 days. The rash dries, becomes encrusted, and heals in another 5–10 days. The pain and dysesthesia of herpes zoster generally last no longer than 4 weeks. They may also occur without a rash (herpes zoster sine herpete).

Complications. Elderly and immunocompromised persons are at increased risk for complications. Pain that persists more than 4 weeks after the cutaneous manifestations have healed is called postherpetic neuralgia and is most common in the cranial and thoracic dermatomes.

Cranial nerve involvement may cause unilateral or bilateral ocular complications (ophthalmoplegia, keratoconjunctivitis, visual impairment) or Ramsay–Hunt syndrome (facial palsy, hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo). Other cranial nerves (IX, X, XII) are rarely affected. Further complications include Guillain–Barré syndrome, myelitis, segmental muscular paresis/ atrophy, myositis, meningitis, ventriculitis, encephalitis, autonomic disturbances (anhidrosis, complex regional pain syndrome), generalized herpes zoster, and vasculitis (ICA and its branches, basilar artery). The viral pathogen is detected in CSF with the polymerase chain reaction.

Virustatic therapy. Acyclovir: 5 mg/kg i. v. q8h or 800 mg p.o. 5 times daily; brivudine: 125 mg p.o. 4 times daily; famcyclovir: 250 mg p.o. 3 times dialy; or valacyclovir: 1 g p.o. 3 times daily. Treatment is continued for 5–7 days. These agents are only effective during the viral replication phase. Intrathecal administration of methylprednisolone is effective in postherpetic neuralgia.

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

|

|

CNS Infections |

|

|

|

Papule |

Viremia |

|

|

|

|

|

||

Scab formation |

|

|

|

|

Macule |

Vesicle |

|

System |

|

Varicella |

|

Portals of entry |

Nervous |

|

(different stages of efflorescence) |

|

Central |

||

|

|

Centripetal axonal |

||

|

|

transport |

|

|

Spread via spinal dorsal root |

|

|

||

|

|

Ganglionic |

|

|

|

|

latency phase |

|

|

Intraneuronal virus (spinal ganglion) |

Reactivation |

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

Group of vesicles on |

|

|

|

|

reddened base |

|

|

|

Varicella |

Zoster |

|

|

|

Acute cerebellar |

Postherpetic |

|

|

|

ataxia |

neuralgia |

|

|

|

Postinfectious |

Cranial nerve palsy |

|

|

|

encephalomyelitis |

Segmental paresis |

|

|

|

Myelitis |

Aseptic |

|

|

|

Guillain-Barré |

meningitis |

|

|

|

syndrome |

Meningoencephalitis |

|

|

|

Reye syndrome |

Myelitis |

|

|

|

Vasculitis (infarct) |

Vasculitis (infarct) |

|

|

|

(Adapted from Johnson, 1998) |

Herpes zoster |

239 |

||

Possible complications of VZV infection |

||||

(“shingles”; dermatome T6/7, left) |

|

|||

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

240

CNS Infections

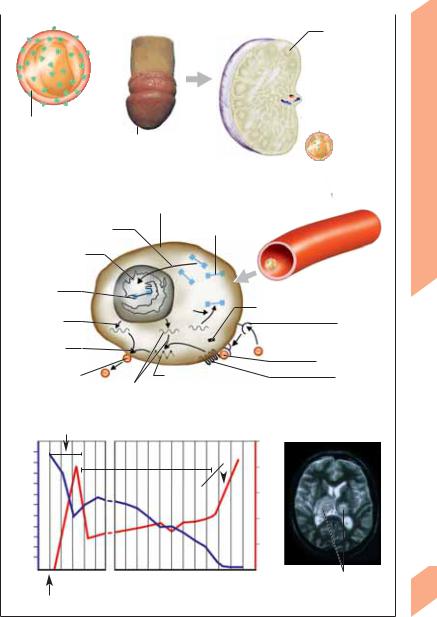

!Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection

Pathogenesis. HIV type 1 (HIV-1) is found worldwide, HIV-2 mainly in western Africa and only rarely in Europe, America, and India. HIV is transmitted by sexual contact, by exposure to contaminated blood or blood products, or from mother to neonate (vertical transmission). It is not transmitted through nonsexual contact during normal daily activities, by contaminated food or water, or by insect bites. In industrialized countries, the mean incubation period for HIV is 9–12 years, and the mean survival time after the onset of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

(AIDS) is 1–3 years. In primary infection (transmitted through mucosal lesions, etc.), the free or cell-bound organisms enter primary target cells in the hematopoietic system (T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells), CNS (macrophages, microglia, astrocytes, neurons), skin (fibroblasts), or gastrointestinal tract (goblet cells). After replicating in the primary target cells, the virions spread to regional lymph nodes, CD4+ T cells, and macrophages, where they replicate rapidly, leading to a marked viremia with dissemination of HIV to other target cells throughout the body. About 7–14 days after this viremic phase, the immune system gains partial control over viral replication, and seroconversion occurs. The subsequent period of clinical latency is characterized by a steady rate of viral replication, elimination of HIV by the immune system, and the absence of major clinical manifestations for several years. Eventually, the immune system fails to keep up with the replicating virus, various immune functions become impaired, and the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count declines sharply. The rising viral load correlates with the progression of HIV infection to AIDS. In the nervous system, HIV initially appears in the CSF, but is later found mainly in macrophages and microglia.

Symptoms and signs. Neurological manifestations can occur at any stage of HIV infection, but usually appear only in the late stages of AIDS. One-half to two-thirds of all HIV-positive individuals develop neurological disturbances as a primary or secondary complication of HIV infection or of a concomitant disease.

Primary HIV infection. Early manifestations at the time of seroconversion are rare; these in-

clude acute reversible encephalitis or aseptic meningitis (p. 234), cranial nerve deficits (especially facial nerve palsy), radiculitis, or myelitis. Neurological signs are usually late manifestations of HIV infection. HIV encephalopathy progresses over several months and is characterized by lethargy, headache, increasing social withdrawal, insomnia, forgetfulness, lack of concentration, and apathy. Advanced AIDS is accompanied by bradyphrenia, impaired ocular pursuit, dysarthrophonia, incoordination, myoclonus, rigidity, and postural tremor. Incontinence and central paresis develop in the final stages of the disease. CT of the brain reveals generalized atrophy, and MRI reveals multifocal or diffuse white-matter lesions. The CSF examination may be normal or reveal a low-grade pleocytosis and an elevated protein concentration. EEG reveals increased slow-wave activity. Other neurological manifestations include HIV myelopathy (vacuolar myelopathy), distal symmetrical polyradiculoneuropathies, mononeuritis multiplex, and polymyositis.

Secondary complications of HIV infection include opportunistic CNS infections (toxoplasmosis, cryptococcal meningitis, aspergillosis, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, cytomegalovirus encephalitis, herpes simplex encephalitis, herpes zoster, tuberculosis, syphilis), tumors (primary CNS lymphoma), stroke (infarction, hemorrhage), and metabolic disturbances

(iatrogenic or secondary to vitamin deficiency). Virustatic treatment. Antiretroviral combination therapy (HAART: highly active antiretroviral therapy).

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

|

|

|

CNS Infections |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spread in regional |

HIV replication |

|||

lymph node |

(lymph node) |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Primary

infection

HIV-1

Mucosal lesion

|

HIV replication cycle in host cell |

|

|

|

Chromosomal integration |

Nonintegrated DNA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cellular DNA |

|

|

|

Viremia, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

dissemination |

Integrated |

|

|

|

|

proviral DNA |

|

|

|

Genomic RNA |

|

|

rT* |

|

|

Transcription |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adsorption |

|

of viral genome |

|

|

|

(virus gp120 + CD4+ receptor) |

Construction |

|

|

|

|

of virions |

|

|

|

Viral penetration |

|

|

|

|

|

Release of virions |

mRNA, |

Protein synthesis, |

|

Co-receptor |

|

processing of gp160, |

|

|

|

|

translation |

envelope, capsid |

|

|

Pathogenesis of HIV infection (*rT = reverse transcriptase)

CD4+ T |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HIV-1 RNA |

|

|

cells/ml) |

|

|

Early manifestation, viremia, dissemination |

copies/ml plasma) |

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

107 |

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Death |

|

|

|

1000 |

|

|

|

|

Clinical latency |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

106 |

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Opportunistic |

|

|

105 |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

diseases |

|

|

|

|||||

500 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

104 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

103 |

|

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

102 |

|

|

Primary |

3 6 9 12 |

1 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

10 |

CNS toxoplasmosis (axial |

||||||

(Weeks) |

|

|

|

(Years) |

|

|

|

T2-weighted MRI scan) |

|||||||

infection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

Course of HIV infection (number of CD4+ lymphocytes and HIV)

Central Nervous System

241

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

CNS Infections

|

! Poliomyelitis |

|

|

|

Pathogenesis. There are three types |

of |

|

|

poliovirus: type 1 (ca. 85% of all infections), type |

||

|

2 and type 3. Like other enteroviruses (e. g., cox- |

||

|

sackievirus, echovirus, and hepatitis-A virus), |

||

|

they are transmitted via the fecal–oral and oral– |

||

|

oral routes, and poor sanitary conditions favor |

||

|

their spread. Having entered the body, the vir- |

||

|

ions infiltrate epithelial cells, where they repli- |

||

|

cate, and then spread to the lymphatic tissues of |

||

System |

the nasopharynx (tonsils) and intestinal wall |

||

(Peyer’s patches). A second replication phase |

|||

(6–8 days) is followed by hematogenous dis- |

|||

|

|||

|

semination (viremia), with nonspecific symp- |

||

Nervous |

toms. Polioviruses reach the CNS via the blood- |

||

in the saliva for 3–4 days and in the feces for 3–4 |

|||

|

stream and can produce signs of poliomyelitis |

||

|

10–14 days after infection. The virus is present |

||

Central |

weeks. The infected individual becomes |

im- |

|

mune only to the specific type of poliovirus that |

|||

|

|||

caused the infection. The viral pathogen can be detected in throat smears and feces by serology or by the polymerase chain reaction.

Symptoms and signs. 90–95% of all poliovirus infections remain asymptomatic (occult immunization). Roughly 5–10% of infected persons develop abortive poliomyelitis, while only 1–2% go on to develop major spinal, bulbar, or encephalitic disease.

Minor poliomyelitis (abortive type) has nonspecific manifestations including fever, headache, sore throat, limb pain, lethargy, and gastrointestinal disturbances (nausea, anorexia, diarrhea, constipation), which resolve in 4 days at most, without CNS involvement.

Major poliomyelitis (preparalytic and paralytic types). Either immediately or after a latency period of 2–3 days, fever rises and organ manifestations appear, with a meningitic syndrome (preparalytic stage) that may be followed by paralysis in the later course of the disease (paralytic stage). The meningitis of the preparalytic stage exhibits typical features of aseptic meningitis as well as marked generalized weakness and apathy. It resolves in about one-half of cases; in the other half, increasing myalgia and stiffness herald the onset of the paralytic stage.

242The spinal form (most common) causes flaccid paresis (usually with asymmetrical proximal

weakness) and areflexia, mainly in the lower

limbs. The paresis may worsen over 3–5 days; its severity is highly variable. Some patients develop paresthesiae without sensory loss or autonomic dysfunction (urinary retention, hypohidrosis, constipation). Muscle atrophy develops within a week of the onset of paralysis.

Bulbar poliomyelitis develops in some 10% of patients (in isolated form, or concurrently with spinal poliomyelitis), involving CN VII, IX, and X to produce dysphagia and dysphonia. Involvement of the brain stem reticular formation causes hemodynamic fluctuations, respiratory insufficiency or paralysis, and gastric atony. The encephalitic form is very rare; it may be accompanied by autonomic dysfunction (p. 222).

Postpolio syndrome. Newly arising manifestations in a patient who recovered from poliomyelitis at least 10 years earlier with stable neurological deficits in the intervening time. Postpolio syndrome is characterized by general symptoms (abnormal fatigability, intolerance to cold, cyanosis of the affected limbs, etc.), arthralgias, and increasing neuromuscular deficits (exacerbation of earlier weakness, weakness of previously unaffected muscles, new atrophy), sometimes accompanied by dysphagia, respiratory insufficiency, and sleep apnea.

Prevention. Subcutaneous immunization with inactivated polioviruses (e. g., Salk vaccine), followed by a first booster in 6–8 weeks and a second booster in 8–12 months.

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.